The Freedom of Information Act and the Ecology of Transparency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Turns the Other Way As Judges Make Findings About Torture and Other Abuse

USA SEE NO EVIL GOVERNMENT TURNS THE OTHER WAY AS JUDGES MAKE FINDINGS ABOUT TORTURE AND OTHER ABUSE Amnesty International Publications First published in February 2011 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2011 Index: AMR 51/005/2011 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 Judges point to human rights violations, executive turns away ........................................... 4 Absence -

WHISTLEBLOWERS and LEAKERS NEWSLETTER, Series 2, #4, October 3, 2019

-- OMNI WHISTLEBLOWERS AND LEAKERS NEWSLETTER, Series 2, #4, October 3, 2019. https://jamesrichardbennett.blogspot.com/2019/10/whistleblowers-and-leakers- newsletter-4.html Compiled by Dick Bennett for a Culture of Peace, Justice, and Ecology http://omnicenter.org/donate/ Series 2 #1 May 18, 2015 http://jamesrichardbennett.blogspot.com/2015/05/whistleblowers-and-leakers- newsletter.html #2 Aug. 6, 2016 http://jamesrichardbennett.blogspot.com/2016/08/whistleblowers-and-leakers- newsletter.html #3 Dec. 13, 2018 https://jamesrichardbennett.blogspot.com/2018/12/whistleblower-newsletter-series-2- 3.html CONTENTS: WHISTLEBLOWERS AND LEAKERS NEWSLETTER, Series 2, #4, October 3, 2019. Reporting in the Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette Whistleblower, the Newsletter of Government Accountability Project Bravehearts by Mark Hertsgaard Snowden’s New Book, Permanent Record Jesselyn Radack’s memoir Traitor: The Whistleblower and the American Taliban Whistleblowers Thomas Drake and John Kiriakou Army Reserve Captain, Brittany Ramos Debarros Film: War on Whistleblowers: Free Press and the National Security State TEXTS RECENT ARTICLES IN THE NADG. I can’t compare its reporting of wb and leakers to that of other newspapers, but it is reporting these heroes of truth and democracy, and very well it appears at least at this tense moment in time. Here are examples I have gathered recently (and have in a file) in reverse chronological order. Julian Barnes, et al. (NYT). “Whistleblower Said to Seek Advice Early.” 10-3-19. Hoyt Purvis. “Whistle-blower Claims Demand Gutsy Response.” 10-2-19. Plante. (Tulsa World, Editorial Cartoon). “Save the American Whistleblower.” 10-1-19. D-G Staff. “Schiff: Panel Will Hear from Whistleblower.” 9-30-19. -

American Civil Liberties Union V. Department of Justice

Case 1:02-cv-02077-ESH Document 1 Filed 10/24/02 Page 1 of 12 • 0 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION 125 Broad Street New York, NY 10004, and ELECTRONIC PRIVACY INFORMATION CENTER 1718 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 200 Washington, DC 20009, and AMERICAN BOOKSELLERS FOUNDATION FOR FREE EXPRESSION 139 Fulton Street., Suite 302 New York, NY 10038, CASE NUJ.!BER 1: 02CV02077 ;(' and JUDGE: Ellen Segal Huvelle . DECK TYPE: FOIA/Privacy Act FREEDOM TO READ FOUNDATION 50 East Huron Street, DATE STAMP, 10/24/2002 Chicago, IL 60611, Plaintiffs, v. FILED DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. OCT 2 4 ZOOZ Washington, DC 20530, Defendant. ........ COMPLAINT FOR INJUNCTIVE RELIEF 1. This is an action under the Freedom of Information Act ("FOIA"), 5 U.S.C. § 552, for injunctive and other appropriate relief, and seeking the immediate processing and release of agency records requested by plaintiffs from defendant Department ~--~~----------------- --~~--. ~ --- ~~-~~,_,~,~-,,-,-"~------------------------- Case 1:02-cv-02077-ESH Document 1 Filed 10/24/02 Page 2 of 12 0 0 of Justice ("DOJ") and DOJ's component, Federal Bureau of Investigation ("FBI"). 2. Plaintiffs' FOIA request seeks the release of records related to the government's implementation of the USA PATRIOT Act ("Patriot Act" or "Act"), Pub. L. No. 107-56, 115 Stat. 272 (Oct. 26, 2001), legislation that was passed in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks. Neither this suit nor the underlying FOIA request questions the importance of safeguarding national security. However, there has been growing public concern about the scope of the Patriot Act and the government's use of authorities thereunder, particularly in relation to constitutionally protected rights. -

Presidential Documents

Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents Monday, May 8, 2000 Volume 36ÐNumber 18 Pages 943±1020 VerDate 20-MAR-2000 09:10 May 10, 2000 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 1249 Sfmt 1249 W:\DISC\PD08MY00.PRE ATX006 PsN: ATX006 Contents Addresses and Remarks Bill Signings Council of the Americas 30th Washington Federal reporting requirements, statement on ConferenceÐ970 legislation amending certainÐ975 Employment reportÐ1015 Communications to Congress Independent Insurance Agents of America's National Legislative ConferenceÐ961 Colombia, message transmitting report on the Iowa, Central High School in DavenportÐ988 national emergency with respect to Kentucky, Audubon Elementary School in significant narcotics traffickersÐ978 OwensboroÐ978 Crude oil, letterÐ945 Michigan Communications to Federal Agencies Commencement address at Eastern Additional Guidelines for Charter Schools, Michigan University in YpsilantiÐ948 memorandumÐ1012 NAACP Fight for Freedom Fund dinner in White House Program for the National DetroitÐ953 Moment of Remembrance, memorandumÐ Minnesota, City Academy in St. PaulÐ990 978 Ohio, roundtable discussion on reforming America's schools in ColumbusÐ1000 Executive Orders Pennsylvania, departure for FarmingtonÐ Actions To Improve Low-Performing 1015 SchoolsÐ985 Radio addressÐ945 Establishing the Kosovo Campaign MedalÐ White House Conference on Raising 987 Teenagers and Resourceful YouthÐ967 Further Amendment to Executive Order White House Correspondents' Association 11478, Equal Employment Opportunity in dinnerÐ946 Federal GovernmentÐ977 (Continued on the inside of the back cover.) Editor's Note: The President was in Farmington, PA, on May 5, the closing date of this issue. Releases and announcements issued by the Office of the Press Secretary but not received in time for inclusion in this issue will be printed next week. WEEKLY COMPILATION OF regulations prescribed by the Administrative Committee of the Federal Register, approved by the President (37 FR 23607; 1 CFR Part 10). -

Democracy Now!: What the Prosecution of NSA Whistleblower Thomas Drake Is Really About 27.12.16 18:18

Democracy Now!: What the Prosecution of NSA Whistleblower Thomas Drake is Really About 27.12.16 18:18 Buchen Sie hier Ihr Flugerlebnis! flyipilot.de JESSELYN RADACK (/BLOGS/JESSELYN-RADACK) Blog (/blogs/Jesselyn-Radack) Stream (/user/Jesselyn Radack/stream) Democracy Now!: What the Prosecution of NSA Whistleblower Thomas Drake is Really About (/stories/2011/5/18/977111/- ) By Jesselyn Radack (/user/Jesselyn%20Radack) Wednesday May 18, 2011 · 5:06 PM CEST 8 Comments (8 New) (http://www.dailykos.com/story/2011/5/18/977111/-#comments) ! 25 " 0 # (https://twitter.com/intent/tweet? url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.dailykos.com%2Fstory%2F2011%2F5%2F18%2F977111%2F- &text=Democracy+Now%21%3A+What+the+Prosecution+of+NSA+Whistleblower+Thomas+Drake+is+Really+About) $ RSS I was just on Democracy Now! (/user/Jesselyn (http://www.democracynow.org/2011/5/18/inside_obamas_orw RECOMMENDED LIST % (/USER/RECOMMENDED/HISTORY) Radack/rss.xml) ellian_world_where_whistleblowing) discussing the prosecution of whistleblower Thomas Drake, who used to be a senior Message to my Trump-supporting Facebook executive at the National Security Agency (NSA). I'm glad friends (/stories/2016/12/26/1614776/-Message-to- TAGS people are finally paying attention to this case, thanks to Jane my-Trump-supporting-Facebook-friends) Mayer's explosive cover story in the New Yorker ! 232 & 146 (/stories/2016/12/26/1614776/-Message-to-my-Trump-supporting-Facebook-friends) #Democracy Now Mommadoc (/user/Mommadoc) (/news/Democracy (http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2011/05/23/110523fa_fa Now) ct_mayer), -

Intelligence Legalism and the National Security Agency's Civil Liberties

112 Harvard National Security Journal / Vol. 6 ARTICLE Intelligence Legalism and the National Security Agency’s Civil Liberties Gap __________________________ Margo Schlanger* * Henry M. Butzel Professor of Law, University of Michigan. I have greatly benefited from conversations with John DeLong, Mort Halperin, Alex Joel, David Kris, Marty Lederman, Nancy Libin, Rick Perlstein, Becky Richards, and several officials who prefer not to be named, all of whom generously spent time with me, discussing the issues in this article, and many of whom also helped again after reading the piece in draft. I would also like to extend thanks to Sam Bagenstos, Rick Lempert, Daphna Renan, Alex Rossmiller, Adrian Vermeule, Steve Vladeck, Marcy Wheeler, Shirin Sinnar and other participants in the 7th Annual National Security Law Workshop, participants at the University of Iowa law faculty workshop, and my colleagues at the University of Michigan Legal Theory Workshop and governance group lunch, who offered me extremely helpful feedback. Jennifer Gitter and Lauren Dayton provided able research assistance. All errors are, of course, my responsibility. Copyright © 2015 by the Presidents and Fellows of Harvard College and Margo Schlanger. 2015 / Intelligence Legalism and the NSA’s Civil Liberties Gaps 113 Abstract Since June 2013, we have seen unprecedented security breaches and disclosures relating to American electronic surveillance. The nearly daily drip, and occasional gush, of once-secret policy and operational information makes it possible to analyze and understand National Security Agency activities, including the organizations and processes inside and outside the NSA that are supposed to safeguard American’s civil liberties as the agency goes about its intelligence gathering business. -

A Public Accountability Defense for National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers

A Public Accountability Defense For National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Yochai Benkler, A Public Accountability Defense For National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers, 8 Harv. L. & Pol'y Rev. 281 (2014). Published Version http://www3.law.harvard.edu/journals/hlpr/files/2014/08/ HLP203.pdf Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12786017 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP A Public Accountability Defense for National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers Yochai Benkler* In June 2013 Glenn Greenwald, Laura Poitras, and Barton Gellman be- gan to publish stories in The Guardian and The Washington Post based on arguably the most significant national security leak in American history.1 By leaking a large cache of classified documents to these reporters, Edward Snowden launched the most extensive public reassessment of surveillance practices by the American security establishment since the mid-1970s.2 Within six months, nineteen bills had been introduced in Congress to sub- stantially reform the National Security Agency’s (“NSA”) bulk collection program and its oversight process;3 a federal judge had held that one of the major disclosed programs violated the -

Good Chemistry James J

Columbia College Fall 2012 TODAY Good Chemistry James J. Valentini Transitions from Longtime Professor to Dean of the College your Contents columbia connection. COVER STORY FEATURES The perfect midtown location: 40 The Home • Network with Columbia alumni Front • Attend exciting events and programs Ai-jen Poo ’96 gives domes- • Dine with a client tic workers a voice. • Conduct business meetings BY NATHALIE ALONSO ’08 • Take advantage of overnight rooms and so much more. 28 Stand and Deliver Joel Klein ’67’s extraordi- nary career as an attorney, educator and reformer. BY CHRIS BURRELL 18 Good Chemistry James J. Valentini transitions from longtime professor of chemistry to Dean of the College. Meet him in this Q&A with CCT Editor Alex Sachare ’71. 34 The Open Mind of Richard Heffner ’46 APPLY FOR The venerable PBS host MEMBERSHIP TODAY! provides a forum for guests 15 WEST 43 STREET to examine, question and NEW YORK, NY 10036 disagree. TEL: 212.719.0380 BY THOMAS VIncIGUERRA ’85, in residence at The Princeton Club ’86J, ’90 GSAS of New York www.columbiaclub.org COVER: LESLIE JEAN-BART ’76, ’77J; BACK COVER: COLIN SULLIVAN ’11 WITHIN THE FAMILY DEPARTMENTS ALUMNI NEWS Déjà Vu All Over Again or 49 Message from the CCAA President The Start of Something New? Kyra Tirana Barry ’87 on the successful inaugural summer of alumni- ete Mangurian is the 10th head football coach since there, the methods to achieve that goal. The goal will happen if sponsored internships. I came to Columbia as a freshman in 1967. (Yes, we you do the other things along the way.” were “freshmen” then, not “first-years,” and we even Still, there’s no substitute for the goal, what Mangurian calls 50 Bookshelf wore beanies during Orientation — but that’s a story the “W word.” for another time.) Since then, Columbia has compiled “The bottom line is winning,” he said. -

Spring Taps 2020

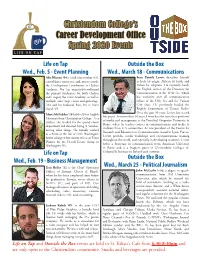

Christendom College’College’ss CarCareereer Development Office Spring 2020 Events Life on Tap Outside the Box Wed., Feb. 5 - Event Planning Wed., March 18 - Communications Alex Klassen ‘04 is a full time mother of 6, Sean Patrick Lovett describes himself retired dance instructor, and, most recently, as Irish by origin, African by birth, and the Development Coordinator at Chelsea Italian by adoption. He currently heads Academy. She has organized/coordinated the English section of the Dicastery for the primary fundraisers for both Chelsea Communication of the Holy See, which and Gregory the Great Academy, as well as has authority over all communication multiple other large events and gatherings. offices of the Holy See and the Vatican Alex and her husband, Ron, live in Front City State. He previously headed the Royal, VA. English Department of Vatican Radio. Over the past 40 years, Lovett has served Maria McFadden ‘18 holds a BA in English five popes. For more than 30 years, Lovett has also served as a professor Literature from Christendom College. As a of media and management at the Pontifical Gregorian University in student, she worked for the special events Rome, where he teaches courses in communications and media to department and directed Swing ‘n Sundaes, students from U.S. universities. As vice president of the Centre for among other things. She initially worked Research and Education in Communication, based in Lyon, France, as a florist at the Inn at Little Washington Lovett provides media workshops and communications training before taking on her current role as an Event throughout the world, and especially in developing countries. -

Presentation of the Portrait the Honorable Ricardo M

JUDGE URBINA’S JUDICIAL COLLEAGUES OLIVER GASCH GLADYS KESSLER WILLIAM B. BRYANT PAUL L. FRIEDMAN AUBREY EUGENE ROBINSON JR. EMMET G. SULLIVAN JUNE L. GREEN JAMES ROBERTSON JOHN H. PRATT COLLEEN KOLLAR-KOTELLY P RESENTATION OF THE P ORTRAIT CHARLES R. RICHEY HENRY H. KENNEDY JR. THOMAS A. FLANNERY RICHARD W. ROBERTS OF LOUIS F. OBERDORFER ELLEN SEGAL HUVELLE HAROLD H. GREENE REGGIE B. WALTON T HE H ONORABLE R ICARDO M. U RBINA JOHN GARRETT PENN JOHN D. BATES U NITED S TATES D ISTRICT J UDGE JOYCE HENS GREEN RICHARD J. LEON NORMA HOLLOWAY JOHNSON ROSEMARY M. COLLYER THOMAS PENFIELD JACKSON BERYL A. HOWELL THOMAS F. HOGAN ROBERT L. WILKINS STANLEY S. HARRIS JAMES E. BOASBERG STANLEY SPORKIN AMY BERMAN JACKSON ROYCE C. LAMBERTH RUDOLPH CONTRERAS JUDGE URBINA’S LAW CLERKS CLAUDIA VON PERVIEUX SARAH GILL BRIAN NUTERANGELO AMY DUNATHAN JUAN MORILLO JAMES CHEN VERONICA WILES TERESA GOODY SUSAN SANTANA JOSHUA PANAS MICHAEL KIM DANIEL ROSENTHAL JOHN TRUONG MACRUI DOSTOURIAN CHRIS LANGELLO JEFF COOK LUIS ANDREW LOPEZ DUSTIN KENALL CATHERINE SZILAGYI AMANDA LUCK J UNE 2 , 2 01 6 JOHN BRENDEL ELIZA BRINK CRYSTAL MORALES ELIKA NARAGHI C EREMONIAL C OURTROOM JULIAN SAENZ JASON PARK JASON HALPERIN TEHSEEN AHMED E. B ARRETT P RETTYMAN U NITED S TATES C OURTHOUSE JESSICA ATTIE CAROLINE DANAUY W ASHINGTON , D.C. JAMES AZADIAN JEROME MAYER-CANTU JUDGE URBINA’S SECRETARY MARIBEL ALVARADO PRESIDING ABOUT THE PORTRAIT Judge Urbina acknowledges with appreciation the generous support for his HON. BERYL A. HOWELL portrait and this event provided by his law clerks, by the Hispanic Bar Associa- CHIEF JUDGE, U.S. -

The Office of Legal Counsel and Torture: the Law As Both a Sword and Shield

Note The Office of Legal Counsel and Torture: The Law as Both a Sword and Shield Ross L. Weiner* And let me just add one thing. And this is a stark contrast here because we are nation [sic] of laws, and we are a nation of values. The terrorists follow no rules. They follow no laws. We will wage and win this war on terrorism and defeat the terrorists. And we will do so in a way that’s consistent with our values and our laws, and consistent with the direction the President laid out.1 —Scott McClellan, Spokesman to President George W. Bush, June 22, 2004 * J.D., expected May 2009, The George Washington University Law School; B.A., 2004, Colgate University. I would like to thank Kimberly L. Sikora Panza and Charlie Pollack for reading early drafts and guiding me on my way. I am indebted to the editors of The George Washington Law Review for all of their thoroughness and dedication in preparing this Note for publication. Finally, thank you to my parents, Tammy and Marc Levine, and Howard and Patti Weiner, for all their hard work. 1 Press Briefing, White House Counsel Judge Alberto Gonzales, Dep’t of Defense (“DoD”) Gen. Counsel William Haynes, DoD Deputy Gen. Counsel Daniel Dell’Orto, and Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence Gen. Keith Alexander (June 22, 2004) [hereinafter Press Briefing], available at http://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2004/06/ 20040622-14.html. February 2009 Vol. 77 No. 2 524 2009] The Law as Both a Sword and a Shield 525 Introduction On September 11, 2001, nineteen men, each a member of al- Qaeda,2 hijacked and crashed four airplanes, killing nearly 3,000 Americans. -

Download PDF Version

Winter 2016–17 OBAMA’S LEGACY PROFESSOR ROBERT Y. SHAPIRO CONSIDERS THE Columbia PRESIDENT’S TIME IN OFFICE College THE TRANS LIST SELECTIONS FROM PORTRAIT Today PHOTOGRAPHER TIMOTHY GREENFIELD-SANDERS ’74 HOMECOMING VICTORY LIONS SMACK DOWN The DARTMOUTH 9–7 Alumni in the know offer-tos fun, practical how 30 YEARS OF COLUMBIA COLLEGE WOMEN On May 13, 1987, Columbia College graduated its first coeducational class, and the College was forever changed. Join us, 30 years later, for a one-day symposium as we reflect on how women have transformed the College experience, ways College women are shaping the world and why coeducation and gender equality remain topics of great importance to us all. Save the Date SATURDAY, APRIL 22, 2017 Learn more: college.columbia.edu/alumni/ccw30years Registration opens in February. To join the Host Committee, email [email protected]. Contents 30 YEARS OF COLUMBIA COLLEGE WOMEN Columbia College CCT Today VOLUME 44 NUMBER 2 WINTER 2016–17 EDITOR IN CHIEF Alex Sachare ’71 EXECUTIVE EDITOR Lisa Palladino DEPUTY EDITOR 24 12 28 Jill C. Shomer CLASS NOTES EDITOR Anne-Ryan Heatwole JRN’09 FORUM EDITOR Rose Kernochan BC’82 CONTRIBUTING WRITER features Shira Boss ’93, JRN’97, SIPA’98 EDITORIAL INTERN 12 Aiyana K. White ’18 ART DIRECTOR The Experts Eson Chan Alumni in the know offer fun, practical how-tos. Published quarterly by the Columbia College Office of By Alexis Boncy SOA’11; Shira Boss ’93, JRN’97, SIPA’98; Alumni Affairs and Development Anne-Ryan Heatwole JRN’09; Kim Martineau JRN’97, SPS’14; for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends of Columbia College.