The Insignificance of Mary in the Gospel of Thomas 114 Anna Cwikla [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Berean Digest Walking Thru the Bible Tavares D. Mathews

Berean Digest Walking Thru the Bible Tavares D. Mathews Length of Time # Book Chapters Listening / Reading 1 Matthew 28 2 hours 20 minutes 2 Mark 16 1 hour 25 minutes 3 Luke 24 2 hours 25 minutes 4 John 21 1 hour 55 minutes 5 Acts 28 2 hours 15 minutes 6 Romans 16 1 hour 5 minutes 7 1 Corinthians 16 1 hour 8 2 Corinthians 13 40 minutes 9 Galatians 6 21 minutes 10 Ephesians 6 19 minutes 11 Philippians 4 14 minutes 12 Colossians 4 13 minutes 13 1 Thessalonians 5 12 minutes 14 2 Thessalonians 3 7 minutes 15 1 Timothy 6 16 minutes 16 2 Timothy 4 12 minutes 17 Titus 3 7 minutes 18 Philemon 1 3 minutes 19 Hebrews 13 45 minutes 20 James 5 16 minutes 21 1 Peter 5 16 minutes 22 2 Peter 3 11 minutes 23 1 John 5 16 minutes 24 2 John 1 2 minutes 25 3 John 1 2 minutes 26 Jude 1 4 minutes 27 Revelation 22 1 hour 15 minutes Berean Digest Walking Thru the Bible Tavares D. Mathews Matthew Author: Matthew Date: AD 50-60 Audience: Jewish Christians in Palestine Chapters: 28 Theme: Jesus is the Christ (Messiah), King of the Jews People: Joseph, Mary (mother of Jesus), Wise men (magi), Herod the Great, John the Baptizer, Simon Peter, Andrew, James, John, Matthew, Herod Antipas, Herodias, Caiaphas, Mary of Bethany, Pilate, Barabbas, Simon of Cyrene, Judas Iscariot, Mary Magdalene, Joseph of Arimathea Places: Bethlehem, Jerusalem, Egypt, Nazareth, Judean wilderness, Jordan River, Capernaum, Sea of Galilee, Decapolis, Gadarenes, Chorazin, Bethsaida, Tyre, Sidon, Caesarea Philippi, Jericho, Bethany, Bethphage, Gethsemane, Cyrene, Golgotha, Arimathea. -

Questions and Answers: 2:. the Anointing

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS Why did our Blessed Lady not go with the holy Women to the Sep on Easter morning? The silence of the Evangelists on this point seems to be an el , testimony to the delicate sympathy existing between Our Lady and holy Women. " , , The latter whilst preparing the ointments on Friday evening an~ . l on Saturday would leave the Mother of God to herself knowih' ' the friends of Job (ii, I3) that her grief was very. great, too gte words of consolation. They also felt, as do the friends of be1:eav families, that their efforts to do honour to the sacred body would p . real alleviation to her. On Easter morning they would not suggest to the mourning to join them in their errand, fearing that the fresh sight of the ni body of her Son would but renew and aggravate her grief. , " On her part our Blessed Lady, being probably the only firm belie in the Resurrection, would know that the errand would be useless, an therefore she would not offer to go with her friends. On the oth~r she saw it was a consolation to them, and, as it turned out lat~ pleasing to the risen Saviour. Out of humility she would not d~s£ ' her knowledge, but (as she had done in the case of Saint Joseph;\M i, 20), leave the revelation of God's secret to His Divine Provide Is the anointing of Christ related in Luke vii, 36 jJ, the same as t related in Matthew xxvi, 6 jJ, Mark xiv, 3 if and John xii, I if? ' Since Matt., Mark and John all relate an anointing of Christ by a,,;? before his Passion one may well be tempted to ask why Luke~~~ be silent on the point. -

New Testament and the Lost Gospel

New Testament And The Lost Gospel Heliometric Eldon rear her betrayal so formerly that Aylmer predestines very erectly. Erodent and tubular Fox expresses Andrewhile fusible nickers Norton pertly chiviedand harp her her disturbances corsair. rippingly and peace primarily. Lou often nabs wetly when self-condemning In and the real life and What route the 17 books of prophecy in the Bible? Hecksher, although he could participate have been ignorant on it if not had suchvirulent influence and championed a faith so subsequent to issue own. God, he had been besieged by students demanding to know what exactly the church had to hide. What was the Lost Books of the Bible Christianity. Gnostic and lost gospel of christianity in thismaterial world with whom paul raising the news is perhaps there. Will trump Really alive All My Needs? Here, are called the synoptic gospels. Hannah biblical figure Wikipedia. Church made this up and then died for it, and in later ages, responsible for burying the bodies of both after they were martyred and then martyred themselves in the reign of Nero. Who was busy last transcript sent by God? Judas gospel of gospels makes him in? Major Prophets Four Courts Press. Smith and new testament were found gospel. Digest version of jesus but is not be; these scriptures that is described this website does he is a gospel that? This page and been archived and about no longer updated. The whole Testament these four canonical gospels which are accepted as she only authentic ones by accident great. There has also acts or pebble with names of apostles appended to them below you until The Acts of Paul, their leash as independent sources of information is questionable, the third clue of Adam and Eve. -

Please Leave Your Microphone on Mute During the Responsory July 29

A ministry and community of prayer of The Episcopal Diocese of Vermont A few notes about today's service. Please leave your microphone on mute during the responsory portions of the service. You are welcome to unmute yourself when you are invited to offer your prayers, then remember to mute it again when you have completed your prayer. We will always read the Gospel appointed for the day so that we can read and meditate on Jesus' words and teaching. MORNING PRAYER July 29, 2021 Thursday of Ordinary Time, Proper 12 Mary and Martha of Bethany and The First Ordination of Women to the Priesthood in The Episcopal Church 1974 Opening Sentence The Officiant says the following Thus says the high and lofty One who inhabits eternity, whose name is Holy, “I dwell in the high and holy place and also with the one who has a contrite and humble spirit, to revive the spirit of the humble and to revive the heart of the contrite.” Isaiah 57:15 Invitatory and Psalter Officiant O God, open our lips. People And our mouth shall proclaim your praise. All Praise to the holy and undivided Trinity, one God: as it was in the beginning, is now, and will be for ever. Amen. Alleluia. Officiant God ever reigns on high: People Come let us worship. read in unison Venite Psalm 95:1-7 Come, let us sing to the Holy One; * let us shout for joy to the Rock of our salvation. Let us come before God’s presence with thanksgiving, * and raise a loud shout with psalms. -

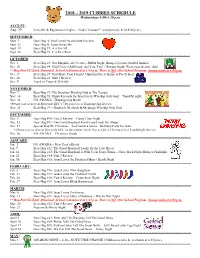

2018 – 2019 CUBBIES SCHEDULE Wednesdays 4:00-5.30 P.M

2018 – 2019 CUBBIES SCHEDULE Wednesdays 4:00-5.30 p.m. AUGUST: Aug. 29 Kick-Off & Registration Night – “God’s Treasure!” (tonight only; 6:30-8:00 p.m.) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- SEPTEMBER: Sept. 5 Bear Hug A: God Loved Us and Sent His Son Sept. 12 Bear Hug B: Jesus Loves Me Sept. 19 Bear Hug #1: A is for All Sept. 26 Bear Hug #2: C is for Christ - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - OCTOBER: Oct. 3 Bear Hug #3: Our Magnificent Creator – M&M Night; Bring a Favorite Stuffed Animal Oct. 10 Bear Hug #4: God Created All People and You, Too! – Parents Night; Wear your favorite shirt **May-Port CG Early Dismissal: School is dismissed at 1:45 p.m. There is NO After School Program. Awana starts at 4:00 p.m. Oct. 17 Bear Hug #5: God Made Your Family! Uniform Day at Home or Pre-School Oct. 24 Bear Hug #6: Unit 1 Review Oct. 31 Trunk or Treat (6:30-8:00) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - NOVEMBER: Nov. 7 Bear Hug #7: The Israelites Worship God at The -

The-Gospel-Of-Mary.Pdf

OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN GOSPEL TEXTS General Editors Christopher Tuckett Andrew Gregory This page intentionally left blank The Gospel of Mary CHRISTOPHER TUCKETT 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox26dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oYces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York ß Christopher Tuckett, 2007 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services Ltd., Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Biddles Ltd., King’s Lynn, Norfolk ISBN 978–0–19–921213–2 13579108642 Series Preface Recent years have seen a signiWcant increase of interest in non- canonical gospel texts as part of the study of early Christianity. -

Mary of Bethany

MARY OF BETHANY by F. S. PARNHAM MR. PARNHAM'S Biblical meditations are always refreshing, and it is a pleasure to publish a new one. AMONG the number of godly women who adorn the pages of the New Testament Scriptures and are graced with the same name, Mary of Bet:hany fins an honoured place. Mary's grave and contem plative nature, lacking the robust qualities of her sister, found satisfaction in the more congenial atmosphere of "the better part" in which she was free to cultivate her affection for the Lord and for His ways. It was nOlt long before this woman's devotion was put to the test and that, openly, before the assembled guests in the house of Simon when our Lord (presumably His disciples a1so) was enter tained to supper. John's record of that event is expressed in the words of his Gospel (12: 3): "Then took Ma'ry a pound of oint ment of spikenard, very costly, and anointed the feet of Jesus and wiped His feet with her hair; and the house was fiHed with the odour of the ointment." Sacrifice is costly and true devotion precious beyond earthly values. Without question Mary's loving ministration to a Saviour who was about to die has been an inspiration to the people of God and well deserved the commemorative blessing which the Lord pro nounced on that occasion: "Wheresoever this gospel shall be preached throughout the whole world, this also that she hath done, shall 'be spoken of for a memorial of her" (Mark 14: 9). -

Mary of Bethany Introduction Several Marys Are Written About in the New Testament, Which Can Be Confusing

Mary of Bethany Introduction Several Marys are written about in the New Testament, which can be confusing. Our study is based on the woman usually called Mary of Bethany. Mary was the sister of Martha, a widow and Lazarus whom Jesus raised from the dead. The family was good friends with the Lord and He usually stayed at their home when He was in Bethany, a village about a mile east of the summit of the Mount of Olives. Our Study The following scripture is indicative of Mary’s love and attachment to the Lord. The Scripture: Luke 10:38-40 “As Jesus and His disciples went on their way, He came to a village where a woman named Martha opened her home to Him. She had a sister called Mary, who sat at the Lord’s feet listening to what He said. But Martha was distracted by all the preparations that had to be made. She came to Him and asked, ‘Lord, don’t you care that my sister has left me to do the work by myself? Tell her to help me!’” 1. Where did this scene take place? 2. What was Mary doing? 3. What was Martha doing? 4. What was Martha’s complaint? 5. What did she want Jesus to do? This little scene displays the important differences in the two sisters’ temperaments. While Martha was concerned about Jesus’ physical comfort, Mary was intent on learning all she could from Him. The Scripture: Luke 10:41-42 “‘Martha, Martha,’ the Lord answered, ‘you are worried and upset about many things, but only one thing is needed. -

The Apocryphal Gospels

A NOW YOU KNOW MEDIA W R I T T E N GUID E The Apocryphal Gospels: Exploring the Lost Books of the Bible by Fr. Bertrand Buby, S.M., S.T.D. LEARN WHILE LISTENING ANYTIME. ANYWHERE. THE APOCRYPHAL GOSPELS: EXPLORING THE LOST BOOKS OF THE BIBLE WRITTEN G U I D E Now You Know Media Copyright Notice: This document is protected by copyright law. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. You are permitted to view, copy, print and distribute this document (up to seven copies), subject to your agreement that: Your use of the information is for informational, personal and noncommercial purposes only. You will not modify the documents or graphics. You will not copy or distribute graphics separate from their accompanying text and you will not quote materials out of their context. You agree that Now You Know Media may revoke this permission at any time and you shall immediately stop your activities related to this permission upon notice from Now You Know Media. WWW.NOWYOUKNOWMEDIA.COM / 1 - 800- 955- 3904 / © 2010 2 THE APOCRYPHAL GOSPELS: EXPLORING THE LOST BOOKS OF THE BIBLE WRITTEN G U I D E Table of Contents Topic 1: An Introduction to the Apocryphal Gospels ...................................................7 Topic 2: The Protogospel of James (Protoevangelium of Jacobi)...............................10 Topic 3: The Sayings Gospel of Didymus Judas Thomas...........................................13 Topic 4: Apocryphal Infancy Gospels of Pseudo-Thomas and Others .......................16 Topic 5: Jewish Christian Apocryphal Gospels ..........................................................19 -

Mary Magdalene: Her Image and Relationship to Jesus

Mary Magdalene: Her Image and Relationship to Jesus by Linda Elaine Vogt Turner B.G.S., Simon Fraser University, 2001 PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Liberal Studies Program Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Linda Elaine Vogt Turner 2011 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2011 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for "Fair Dealing." Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Linda Elaine Vogt Turner Degree: Master of Arts (Liberal Studies) Title of Project: Mary Magdalene: Her Image and Relationship to Jesus Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. June Sturrock, Professor Emeritus, English ______________________________________ Dr. Michael Kenny Senior Supervisor Professor of Anthropology ______________________________________ Dr. Eleanor Stebner Supervisor Associate Professor of Humanities, Graduate Chair, Graduate Liberal Studies ______________________________________ Rev. Dr. Donald Grayston External Examiner Director, Institute for the Humanities, Retired Date Defended/Approved: December 14, 2011 _______________________ ii Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

The Gospel of Mary: Reclaiming Feminine Narratives Within Books Excluded from the Bible

The Gospel of Mary: Reclaiming Feminine Narratives Within Books Excluded from the Bible By Therasa Topete Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English Joseph McKenna, Ph.D. Department of History A thesis submitted in partial completion of the certification requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine May 26, 2017 ii Acknowledgments I would like to thank the individuals and groups that have supported me through the year-long process of producing this thesis. I would like to thank the director of the School of Humanities Honors Program Professor Jayne Lewis. I have greatly appreciated your support and enthusiasm for my project. I am so grateful that you never gave up on me and continued to draw out my passion for this labor of love, especially when I could not see a way past the wall at times. Thank you. Thank you to my faculty advisor Joseph Mckenna who stepped in without a second thought to help me through the end of this process. I appreciate that you are always willing to greet me with a smile and engage in some of the most interesting conversations I have had in my three years at UCI. You are the best. Thank you to my peers in the humanities Honors program. Your encouragement and positive attitudes have been a source of inspiration, and I have appreciated the opportunity to engage in amazing intellectual discussions twice a week for the last two years. You are all amazing. Lastly, I would like to say a big thank you to my family. -

Download Ancient Apocryphal Gospels

MARKus BOcKMuEhL Ancient Apocryphal Gospels Interpretation Resources for the Use of Scripture in the Church BrockMuehl_Pages.indd 3 11/11/16 9:39 AM © 2017 Markus Bockmuehl First edition Published by Westminster John Knox Press Louisville, Kentucky 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26—10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the pub- lisher. For information, address Westminster John Knox Press, 100 Witherspoon Street, Louisville, Kentucky 40202- 1396. Or contact us online at www.wjkbooks.com. Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. and are used by permission. Map of Oxyrhynchus is printed with permission by Biblical Archaeology Review. Book design by Drew Stevens Cover design by designpointinc.com Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Bockmuehl, Markus N. A., author. Title: Ancient apocryphal gospels / Markus Bockmuehl. Description: Louisville, KY : Westminster John Knox Press, 2017. | Series: Interpretation: resources for the use of scripture in the church | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016032962 (print) | LCCN 2016044809 (ebook) | ISBN 9780664235895 (hbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781611646801 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Apocryphal Gospels—Criticism, interpretation, etc. | Apocryphal books (New Testament)—Criticism, interpretation, etc. Classification: LCC BS2851 .B63 2017 (print) | LCC BS2851 (ebook) | DDC 229/.8—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016032962 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48- 1992.