This Is a Fully Online Course. It Will Be Delivered Synchronously Via Zoom at the Scheduled Class Time, and Will Use Blackboard As a Course Management System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate

For publication on or after Monday, March 29, 2010 Media Kit announcing the 2010 PritzKer architecture Prize Laureate This media kit consists of two booklets: one with text providing details of the laureate announcement, and a second booklet of photographs that are linked to downloadable high resolution images that may be used for printing in connection with the announcement of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. The photos of the Laureates and their works provided do not rep- resent a complete catalogue of their work, but rather a small sampling. Contents Previous Laureates of the Pritzker Prize ....................................................2 Media Release Announcing the 2010 Laureate ......................................3-5 Citation from Pritzker Jury ........................................................................6 Members of the Pritzker Jury ....................................................................7 About the Works of SANAA ...............................................................8-10 Fact Summary .....................................................................................11-17 About the Pritzker Medal ........................................................................18 2010 Ceremony Venue ......................................................................19-21 History of the Pritzker Prize ...............................................................22-24 Media contact The Hyatt Foundation phone: 310-273-8696 or Media Information Office 310-278-7372 Attn: Keith H. Walker fax: 310-273-6134 8802 Ashcroft Avenue e-mail: [email protected] Los Angeles, CA 90048-2402 http:/www.pritzkerprize.com 1 P r e v i o u s L a u r e a t e s 1979 1995 Philip Johnson of the United States of America Tadao Ando of Japan presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. presented at the Grand Trianon and the Palace of Versailles, France 1996 1980 Luis Barragán of Mexico Rafael Moneo of Spain presented at the construction site of The Getty Center, presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. -

Cathedral, but It Is Aligned to Ohio's Learning Writing Standards Before the 2017 Revisions and Ohio's State Tests

Columbus City Schools This is an older resource which can provide ideas for teaching the Standards for English Language Arts Curriculum student mastery using The Cathedral, but it is aligned to Ohio's Learning Writing Standards before the 2017 revisions and Ohio's State Tests. Course/Grade Text Type Grade 7 Book Unit Cathedral: The Informative/ Explanatory (15 Days) Story of Its Construction (1120L) Portfolio Writing Prompt: After reading Cathedral, write an essay that describes how a famous building or a specific building in your community was constructed. Research the reasons the structure was built and the way the structure has been used over the years. Include multimedia resources such as a power point, video, posters or other multimedia to clarify your essay. Common Core Writing: Text types, responding to reading, and research The Standards acknowledge the fact that whereas some writing skills, such as the ability to plan, revise, edit, and publish, are applicable to many types of writing, other skills are more properly defined in terms of specific writing types: arguments, informative/explanatory texts, and narratives. Standard 9 stresses the importance of the reading-writing connection by requiring students to draw upon and write about evidence from literary and informational texts. Because of the centrality of writing to most forms of inquiry, research standards are prominently included in this strand, though skills important to research are infused throughout the document. (CCSS, Introduction, 8) Informational Text Informational/explanatory writing conveys information accurately. This kind of writing serves one or more closely related purposes: to increase readers knowledge of a subject, to help readers better understand a procedure or process, or to provide readers with an enhanced comprehension of a concept. -

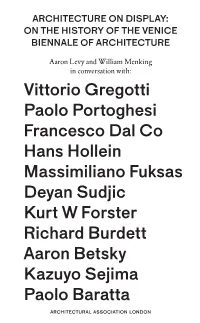

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

400 Buildings 230 Architects 6 Geographical Regions 80 Countries a U R P E Or Am S Ica Fr a Ce Ia

400 Buildings 100 single houses┆53 schools┆21 art galleries 66 museums┆7 swimming pools┆2 town halls 230 Architects 52 office buildings┆33 unibersities┆5 international 6 Geographical Regions airports21 libraries┆5 embassies┆30 hotels 5 railway staions 80 Countries 80Architects dings Buil 125 ia As O ce an ZAHA HADID ARCHITECTS//OMA//FUKSAS//ASYMPTOTE ARCHITECTURE//ANDRÉS ia 6 5 PEREA ARCHITECT//SNØHETTA//BERNARD TSCHUMI//COOP HIMMELB(L)AU//FOSTER + B u i ld in g PARTNERS//UNStudio//laN+//KISHO KUROKAWA ARCHITECT AND ASSOCIATES//STEVEN s s t c e 8 it 0 h A c r HOLL ARCHITECTS//JOHN PORTMAN & ASSOCIATES//3DELUXE//TADAO ANDO ARCHITECT r c A h 0 it e 8 c t s & ASSOCIATES//MVRDV//SAUCIER + PERROTTE ARCHITECTES//ACCONCI STUDIO// s g n i d l i DRIENDL*ARCHITECTS//OGRYDZIAK / PRILLINGER ARCHITECTS//URBAN ENVIRONMENTS u B 5 0 ARCHITECTS//ORTLOS SPACE ENGINEERING//MOSHE SAFDIE AND ASSOCIATES INC.// 2 LOMA //JENSEN & SKODVIN ARKITEKTKONTOR AS+ARNE HENRIKSEN ARKITEKTER AS + e p o C-V HØLMEBAKK ARKITEKT//HENN ARCHITEKTEN//GIENCKE & COMPANY//CHETWOODS r u E A ARCHITECTS//AAARCHITECTEN//ABALOS+SENTKIEWICZ ARQUITECTOS//VARIOUS f r i ARCHITECTS//DENTON CORKER MARSHALL//SAMYN AND PARTNERS//ANTOINE PREDOCK// c a FREE Fernando Romero...... 3 5 s B t c u e i t l i d h i n c r g s A 0 8 8 0 s A g r c n i h d i l t i e u c B t s 0 9 a c i r e m A h t r o N S o u t h A m e r i c s t a c e t i h c r A 0 8 1 s 1 g n 5 i d B l i u ISBN 978-978-12585-2-6 7 8 9 7 8 1 Editorial Department of Global Architecture Practice Editorial Department of Global Architecture -

C:\Users\Gutschow\Documents\CMU Teaching\Postwar Modern

Arch. 48-350 -- Postwar Modern Architecture, S’13 Prof. Gutschow, Class #5 DISCUSSION: WHAT IS POSTWAR MODERN? Discuss: Joedicke, J. “Introduction,” Architecture Since 1945 (1969) Goldhagen & Legault, “Introduction: Critical Themes of Postwar Modernism,” in Anxious Modernisms Goldhagen, “Coda: Reconceptualizing Modernism,” in Anxious Modernisms Ockman: “Introduction,” in Architecture Culture, 1943-1968 Differentiate: Prewar Modernism; Postwar Modernism; Postmodernism Critical Themes of Postwar Modernism: Anxiety, Popular Culutre, Consumer Culture, Everyday Life, Anti- Architecture, Democratic Freedom, Homo Ludens (play), Primitivism, Authenticity, Architecture’s History, Regionalism, Place, Skepticism & Infatuation with Technology. Postwar Modern Architects & Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureates 2010: SANAA, Kazuyo Sejima + Ryue Nishizawa of Japan. 2009: Peter Zumthor of Switzerland 2008: Jean Nouvel of France 2007: Richard Rogers of the United Kingdom 2006: Paulo Mendez da Rocha of Brazil 2005: Thom Mayne of the United States 2004: Zaha Hadid of the United Kingdom 2003: Jorn Utzon of Denmark 2002: Glenn Murcutt of Australia 2001: Herzog and de Meuron of Switzerland 2000: Rem Koolhaas of The Netherlands 1999: Norman Foster of the United Kingdom 1998: Renzo Piano of Italy 1997: Sverre Fehn of Norway 1996: Rafael Moneo of Spain presented 1995: Tadao Ando of Japan 1994: Christian de Portzamparc of France 1993: Fumihiko Maki of Japan 1992: Alvaro Siza of Portugal 1991: Robert Venturi of the United States 1990: Aldo Rossi of Italy 1989: Frank O. Gehry of the United States 1988: Gordon Bunshaft of the United States and Oscar Niemeyer of Brazil 1987: Kenzo Tange of Japan 1986: Gottfried Boehm of Germany 1985: Hans Hollein of Austria 1984: Richard Meier of the United States 1983: Ieoh Ming Pei of the United States 1982: Kevin Roche of the United States 1981: James Stirling of Great Britain 1980: Luis Barragan of Mexico 1979: Philip Johnson of the United States. -

Altelier Hans Hollein Principal Architect(S): Hollein, Hans

ALTELIER HANS HOLLEIN PRINCIPAL ARCHITECT(S): HOLLEIN, HANS LOCATION: VIENNA, AUSTRIA FIRM OPENED: 1964 EMPLOYEES: 1 FIRM PHILOSOPHY Known as a universal artist, Hollein’s design philosophies are derived from the idea that one must avoid narrow and easily defendable positions to achieve original and quality design. Hollein says that evolution of early design ideas should be re-examined and realized in future work. He believes that design is not a profession to be pigeon-holed, and encourages exploration of the aforementioned design elements in other ways than just architecture. HISTORY Hans Hollein studied architecture and urban planning at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in Chicago until 1959. In 1960 he finished his studies at the University of California in Berkeley as Master of Architecture. He established his own solo architectural studio in Vienna in 1964. He has since realized works in Austria, France, Germany, Iran, Italy, Spain, Russia, USA, Peru, and Japan. Hollein used to employ interns to help around the office. However, in 2010 he joined a partnership with ZT-GmbH, another architectural firm, leaving his solo studio to focus on his art and furniture design. His most notable awards include the following: the Pritzker Architecture Prize, 1985; the Reynolds Memorial Award, 1966 and 1984; the Prize of the City of Vienna for Architecture, 1974; the Grand Austrian State Awards, 1983; the Austrian Ehrenzeichen für Wissenschaft und Kunst, 1990; the Goldenes Ehrenzeichen für Verdienste um das Land Wien, 1994; the Grosse Verdienstkreuz des Verdienstordens der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 1997; and the Arnold W. Brunner Memorial Prize of Architecture in New York, 2004. -

DENTRO LA STRADA NOVISSIMA 20 Facades Designed by 20 Architects Including Frank O

DENTRO LA STRADA NOVISSIMA 20 facades designed by 20 architects including Frank O. Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, Hans Hollein, Franco Purini, Arata Isozaki, Robert Venturi, Osvald Mathias Ungers draw the Strada Novissima, the exhibition curated by Paolo Portoghesi at the first Biennale of Architecture in 1980 Today at MAXXI, a focus dedicated to that exhibition is an opportunity to reflect on a crucial moment in the history of twentieth century architecture 07 December 2018 - 29 September 2019 www.maxxi.art | #DentroLaStradaNovissima Rome, 6 December 2018. The First International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale curated by Paolo Portoghesi opened on 27 July 1980, and was entitled La Presenza del Passato [The Presence of the Past]. During this Biennale, Paolo Portoghesi proposed the exhibition La Strada Novissima, that involved 20 international architects who created 20 life-size facades to activate a reflection on the theme of the road and create a concrete image of a different way of thinking about architecture. Today the MAXXI, after almost forty years, returns to reflect on this theme with the great exhibition The Street. Where the world is made, and the same Portoghesi curates DENTRO LA STRADA NOVISSIMA an in-depth focus on this crucial moment in the history of twentieth century architecture, which started the international discussion on postmodernism. The Focus will be held at the Architecture Archive Centre from 7 December 2018 to 28 April 2019. As a whole, La Strada Novissima proposed a real 70-metre path and 10 life-size facades per side designed by Ricardo Bofill, Costantino Dardi, Frank O. Gehry, Michael Graves, GRAU, Allan Greenberg, Hans Hollein, Arata Isozaki, Josef Paul Kleihues, Rem Koolhaas, Léon Krier, Charles W. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Everything Is Architecture Bau Magazine from the 60S and 70S.Pdf

ICA 27 September 2015 29 July – ICA 29 July – 27 September 2015 from the from 60s and 70s Bau Magazine from the from 60s and 70s Bau Magazine Everything is Architecture: Everything is Architecture: This display focuses on the Austrian architectural magazine Bau: Zeitschrift für Architektur und Städtebau (Bau: Magazine for Architecture and Urban Planning). Originally named Der Bau, the magazine was published by the Central Association of Austrian Architects and established in 1925 as a trade publication. From 1965 to 1970, its editorship was taken over by a group of pioneering Austrian artists and architects: Sokratis Dimitriou, Günther Feuerstein, Hans Hollein, Oswald Oberhuber, Gustav Peichl and Walter Pichler. The magazine became a platform for debate, innovation and experimentation within architecture and urban planning but also art, design and politics. It contained several different strands of architectural writing and documentation, from both within Austria and the German-speaking world and the broader international scene. Visual and theoretical essays by the editors helped to bring their pioneering architectural ideas to a wider audience. The architecture of forgotten figures such as Josef Hoffmann, Adolf Loos, Rudolph M. Schindler and Ludwig Wittgenstein was celebrated as a way to readdress the historical amnesia following the Second World War. The magazine also showcased the radical work of a younger generation of Austrian architects such as COOP HIMMELB(L)AU and Haus-Rucker-Co, and helped to provide a window to the major international, architectural and artistic scenes of the time, publishing the work of London-based architectural group Archigram and American architects and artists Buckminster Fuller and Claes Oldenburg. -

Discussion Guide

Young Adult Book Discussion Kits Young Adult Book Discussion Kits are available to library patrons for use by home and community discussion groups, as well as teachers in the classroom setting. Each kit contains a set of thirty identical soft-cover books accompanied by a book discussion guide. The guides feature information about the author, reviews of the book, discussion questions, suggested further readings, and other pertinent information. Each kit is packaged in a canvas tote bag and may be borrowed for six weeks. Young Adult Book Discussion Kits may be reserved and sent A Reader’s Guide to to the library branch of your choice for pick up. If you would like to Juvenile Book reserve a kit, please stop by your local library branch or call 574- Discussion Kit 1611 . The kits may also be reserved through our website The David www.lfpl.org . A list of all the kits may be found in the LFPL cata- Macaulay Collection log by typing Book Discussion Kit Young Adult at the title prompt. Xtreme Reads Xtreme Reads Xtreme Reads Children’s & Young Adult Services 301 York Street Xtreme Reads Louisville, KY 40203 Xtreme Reads 502-574-1620 Information for this flyer was partially gathered from the following re- Young Adult Book sources: Discussion Kits Contemporary Authors Online, Thomson Gale, 2004. http://www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com/authors/macaulay/macaulaybio.shtml David Macaulay’s is a very pro- He spent time working as an What the Critics Say… lific children’s illustrator. His 6. David Macaulay says Black and interior designer, middle school teacher, works range from meticulous White is comprised of four stories, and college professor before breaking “Macaulay’s books on architecture architectural drawings to witty or maybe it is really about one into the world of children’s literature. -

SO-Cover Copy.Indd

Bricks Politics& What gets built at Harvard, what doesn’t, and why by Joan Wickersham very year, on a hot summer day, 10 Boston-area architects pile into a van together and drive around for hours looking for beauty. Lately, at least, they haven’t been finding it at Harvard. EThey are members of a jury assembled annually by the Boston Society of Architects to award the Harleston Parker Medal, a prize given to the recent building judged to be “the most beautiful.” It’s not the biggest, fanciest award in the world, or even in the world of architecture (that distinction belongs to the Pritzker Prize, sometimes referred to as “the Nobel of architecture”). But the Parker Medal is a good gauge of how architects—who are both the toughest critics and This elegant and austere office building for the Harvard University Library rose at greatest appreciators of one another’s work—view the aes- 90 Mount Auburn Street after the Cambridge Historical Commission rejected a design by Viennese architect Hans Hollein that would thetic quality of what’s being built around Boston. have been a bold, provocative piece of art that might have begun “a new kind of Since 2000, juries have recognized buildings on the Welles- architecture in Harvard Square.” 50 September - October 2007 Photographs by Jim Harrison ley campus twice, at Northeastern University twice, and at MIT York’s Morgan Library—was hired in 1999 to design a new mu- once. The last time a Harvard building was chosen was in 1994: seum for Harvard’s modern art collection. -

Zgallerymanager MSPM

Thomas Demand ARCHIVMATERIAL / NEW STOP MOTION Sprüth Magers, Berlin November 24, 2018 – January 19, 2019 In the past several years, Thomas Demand has periodically turned his camera away from the models he constructs himself, as content for his well-known photographs, to focus on models he has encountered in the archives and studios of renowned architects. First instigated by the artist’s visits to the John Lautner archives at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, Demand’s Model Studies continued with the paper constructions he photographed at the Tokyo studio of Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa (SANAA). Sprüth Magers is pleased to present ARCHIVMATERIAL, the third iteration of Demand’s contemplative series, which concentrates on models by the Viennese artist-architect Hans Hollein. Also on view NEW STOP MOTION, two of the artist’s mesmerizing stop motion animations completed in 2016 and 2018. A radical thinker and an instigator in the history of postmodern architecture, Hans Hollein (1934–2014) sought to expand the concept of architecture to encompass all forms of environments, from space suits to advertisement spreads to telecommunications systems. As he declared in Bau magazine in 1968: “Architects must cease to think only in terms of buildings... Everyone is an architect. Everything is architecture.” The title of Demand’s exhibition, ARCHIVMATERIAL, is a playful nod to the theoretical seriousness of conceptual manifestos of the 1960s and 1970s, of which Hollein penned his fair share. Presented with the opportunity to explore Hollein’s extensive archives, packed into numerous apartments across Vienna, Demand delved into the architect’s materials.