SO-Cover Copy.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate

For publication on or after Monday, March 29, 2010 Media Kit announcing the 2010 PritzKer architecture Prize Laureate This media kit consists of two booklets: one with text providing details of the laureate announcement, and a second booklet of photographs that are linked to downloadable high resolution images that may be used for printing in connection with the announcement of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. The photos of the Laureates and their works provided do not rep- resent a complete catalogue of their work, but rather a small sampling. Contents Previous Laureates of the Pritzker Prize ....................................................2 Media Release Announcing the 2010 Laureate ......................................3-5 Citation from Pritzker Jury ........................................................................6 Members of the Pritzker Jury ....................................................................7 About the Works of SANAA ...............................................................8-10 Fact Summary .....................................................................................11-17 About the Pritzker Medal ........................................................................18 2010 Ceremony Venue ......................................................................19-21 History of the Pritzker Prize ...............................................................22-24 Media contact The Hyatt Foundation phone: 310-273-8696 or Media Information Office 310-278-7372 Attn: Keith H. Walker fax: 310-273-6134 8802 Ashcroft Avenue e-mail: [email protected] Los Angeles, CA 90048-2402 http:/www.pritzkerprize.com 1 P r e v i o u s L a u r e a t e s 1979 1995 Philip Johnson of the United States of America Tadao Ando of Japan presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. presented at the Grand Trianon and the Palace of Versailles, France 1996 1980 Luis Barragán of Mexico Rafael Moneo of Spain presented at the construction site of The Getty Center, presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. -

Renzo Piano Building Workshop

Renzo Piano Building Workshop Renzo Piano Antonio Belvedere Founding Partner, Chairman Partner-director In charge of the V-A-C Cultural Space, Moscow Company Profile Renzo Piano was born in Genoa in 1937 Born in 1969, Antonio Belvedere graduated into a family of builders. in architecture from the University of The Renzo Piano Building Workshop While studying at Politecnico of Milan Florence. He joined RPBW’s Paris (RPBW) is an international architectural University, he worked in the office of office in 1999, working on phase three practice with offices in Paris and Genoa. Franco Albini. of the Fiat Lingotto factory conversion In 1971, he set up the “Piano & Rogers” project, particularly on the design of the The Workshop is led by eight partner- office in London together with Richard Polytechnic and the Pinacoteca Agnelli. directors, including the founder and Pritzker Rogers, with whom he won the competition He was subsequently lead architect on Prize laureate, architect Renzo Piano, and for the Centre Pompidou. He subsequently the masterplan for Columbia University’s 3 partners. The company permanently moved to Paris. Manhattanville development in New York. employs nearly 130 people. Our 90- From the early 1970s to the 1990s, he Following promotion to Associate in 2004, plus architects are from all around the worked with the engineer Peter Rice, he worked on the masterplan for the ex- world, each selected for their experience, sharing the Atelier Piano & Rice from 1977 Falck area in Milan. enthusiasm and calibre. to 1981. He became a Partner in 2011. Recently The company’s staff has the expertise to In 1981, the “Renzo Piano Building completed projects include the Valletta City provide full architectural design services, Workshop” was established, with 150 staff Gate in Malta. -

Iceland, Scandinavia, England & Scotland

OUR 15TH ARCHITECTURE TOUR JOIN MALCOLM CARVER’S ARCHITECTURE TOUR OF ICELAND, SCANDINAVIA, ENGLAND & SCOTLAND London, Manchester, Glasgow, Reykjavik, Oslo, Aalborg & Copenhagen 4 -24 August 2018 A tour for architects and everybody that enjoys beautiful buildings ARCHITECTURE TOUR OF The tour at a glance… Three previous architecture tours to this delightful part of the world were limited ICELAND, to the work of the renowned modernist architect, Alvar Aalto in Finland. This grand tour of Scandinavia extends beyond Finland and begins in the City of London where many may wish to explore before we begin our northern hemisphere SCANDINAVIA, journey. Scandinavia has long been on our horizon particularly with enthusiastic ENGLAND & SCOTLAND encouragement from our many friends and previous eminent guests who we hope will again join another grand architectural pilgrimage. This region of the world has long shown exceptional, original leading modernist trends in architecture, art and Recent contemporary design that continues to inspire the whole world. architecture coupled with Our itinerary includes exciting and outstanding buildings with orientation tours of iconic modern buildings, by the gems in each city, providing a balance of old and new. We have also allowed outstanding award-winning free time for participants to individually enjoy particular buildings and landmarks of their choice, or time to enjoy galleries and museums and share the sheer pleasures and internationally renowned these beautiful cities traditionally have to offer. architects including Norman Foster, Renzo Piano, Jorn Utzon, Santiago Calatrava, Charles Rennie Mackintosh Daniel Libeskind, Denton, Corker Marshall, Stephen Holl and Zaha Hadid. TOUR ITINERARY DAY 7 Friday 10 August 2018 Glasgow Today begins with one of Zaha Hadid’s recent buildings before her sad DAY 1 Saturday 4 August 2018 Departure passing last year, Maggies Centre Kircaldy, then Glasgow School of Art Tour members depart Australian for London. -

![The Pritzker Architecture Prize1998[1]. RENZO PIANO 2](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1482/the-pritzker-architecture-prize1998-1-renzo-piano-2-371482.webp)

The Pritzker Architecture Prize1998[1]. RENZO PIANO 2

Photo by M. Denancé Reconstruction of the Atelier Brancusi, Paris, France — 1997 Photo by C. Richters Photo by M. Denancé The Beyeler Foundation Museum Basel, Switzerland 1997 Ushibuka Bridge linking three islands of the Amakusa Archipelago, Japan — 1997 Photo by Paul Hester The Menil Collection Museum Houston, Texas — 1987 Photo by Paul Hester Drawing illustrating the roof system of “leaves” for adjusting the amount of light admitted to the galleries. Photo by Hickey Robertson The Cy Twombly Gallery at the Menil Collection Museum Houston, Texas — 1995 Photo by Hickey Robertson THE ARCHITECTURE OF RENZO PIANO — A T RIUMPH OF CONTINUING CREATIVITY BY COLIN AMERY AUTHOR AND ARCHITECTURAL CRITIC, THE FINANCIAL TIMES SPECIAL ADVISOR TO THE WORLD MONUMENTS FUND It was modern architecture itself that was honored at the White House in Washington, D.C. on June 17, 1998. The twentieth anniversary of the Pritzker Prize and the presentation of the prestigious award to Renzo Piano made for an extraordinary event. Piano’s quiet character and almost solemn, bearded appearance brought an atmosphere of serious, contemporary creativity to the glamorous event. The great gardens and the classical salons of the White House were filled with the flower of the world’s architectural talent including the majority of the laureates of the previous twenty years. But perhaps the most significant aspect of the splendid event was the opportunity it gave for an overview of the recent past of architecture at the very heart of the capital of the world’s most powerful country. It was rather as though King Louis XIV had invited all the greatest creative architects of the day to a grand dinner at Versailles. -

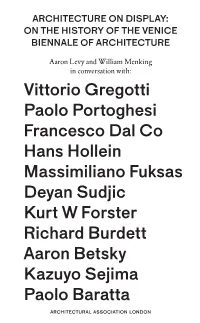

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

Renzo Piano 1998 Laureate Essay

Renzo Piano 1998 Laureate Essay The Architecture of Renzo Piano—A Triumph of Continuing Creativity By Colin Amery Author and Architectural Critic, The Financial Times Special Advisor to the World Monuments Fund It was modern architecture itself that was honored at the White House in Washington, D.C. on June 17, 1998. The twentieth anniversary of the Pritzker Prize and the presentation of the prestigious award to Renzo Piano made for an extraordinary event. Piano’s quiet character and almost solemn, bearded appearance brought an atmosphere of serious, contemporary creativity to the glamorous event. The great gardens and the classical salons of the White House were filled with the flower of the world’s architectural talent including the majority of the laureates of the previous twenty years. But perhaps the most significant aspect of the splendid event was the opportunity it gave for an overview of the recent past of architecture at the very heart of the capital of the world’s most powerful country. It was rather as though King Louis XIV had invited all the greatest creative architects of the day to a grand dinner at Versailles. In Imperial Washington the entire globe gathered to pay tribute to the very art of architecture itself. Renzo Piano was not overwhelmed by the brilliance of the occasion, on the contrary he seized his opportunity to tell the world about the nature of his work. In his own words, he firmly explained that architecture is a serious business being both art and a service. Those are perhaps two of the best words to describe Renzo Piano’s work. -

“Shall We Compete?”

5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall We Compete?” Pedro Guilherme 35 5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall we compete?” Author Pedro Miguel Hernandez Salvador Guilherme1 CHAIA (Centre for Art History and Artistic Research), Universidade de Évora, Portugal http://uevora.academia.edu/PedroGuilherme (+351) 962556435 [email protected] Abstract Following previous research on competitions from Portuguese architects abroad we propose to show a risomatic string of politic, economic and sociologic events that show why competitions are so much appealing. We will follow Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura as the former opens the first doors to competitions and the latter follows the master with renewed strength and research vigour. The European convergence provides the opportunity to develop and confirm other architects whose competences and aesthetics are internationally known and recognized. Competitions become an opportunity to other work, different scales and strategies. By 2000, the downfall of the golden initial European years makes competitions not only an opportunity but the only opportunity for young architects. From the early tentative, explorative years of Siza’s firs competitions to the current massive participation of Portuguese architects in foreign competitions there is a long, cumulative effort of competence and visibility that gives international competitions a symbolic, unquestioned value. Keywords International Architectural Competitions, Portugal, Souto de Moura, Siza Vieira, research, decision making Introduction Architects have for long been competing among themselves in competitions. They have done so because they believed competitions are worth it, despite all its negative aspects. There are immense resources allocated in competitions: human labour, time, competences, stamina, expertizes, costs, energy and materials. -

C O M P a N Y P R O F I

company profile whotectoo is a creative hub of architects whose partners’ background experience spans across many countries and continents: Europe, North America, Middle East and Far East, Australia and Africa. Our people We trust in what we do and how it is conceived selecting the right people with different attitudes, expertise and ambitions but with common qualities: trust, motivation and knowledge. 1 Tectoo is an architectural design firm established by the Architect Susanna Scarabicchi, former partner of Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW). Her expertise, sensitivity and competence have been highly recognized around the world throughout the projects she led and designed over the past 30 years. She developed a commendable portfolio of projects that prompted community regeneration, sense of place and design quality. Tectoo’s cutting-edge approach is also enhanced by the expertise of Architect Andrea Peschiera, with whom Architect Scarabicchi has had a close and productive collaboration during the last five years at RPBW and who joined the firm as partner and director since the early stages, sharing the common focus on technical excellence and experimentation developed through his international experience. Tectoo is deeply rooted by architectural, environmental and social convictions for what designing for the future means. Creating something new in a world everyday more fragile requires the profound awareness that the best building concepts grow by means of a rigorous and innovative approach. Our view is that creating good architecture involves developing and implementing competencies in collaboration with an extensive network of experts from many fields and disciplines whilst engaging in a strong relationship with our clients in order to define common goals. -

Architectural Thought : the Design Process and and the Expectant

184 Drexler, Arthur (1955) The Architecture of Japan, New York Evans, Robin (1986) ‘Translations from drawing to building’, AA Files, no. 12, London Fawcett, Chris (1980) ‘Colin St J Wilson’ in Contemporary Architects, London Fletcher, B.C. (1943) A History of Architecture: On the Comparative Method, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 11th edn Foster, Norman (1996) ‘Carré d’Art’ in The Architecture of Information (ed. Michael Brawne), London Gaskell, Ivan (2000) Vermeer’s Wager: Speculations on Art History, Theory & Museums, London Gideon, Sigfried (1954) Space, Time and Architecture: the growth of a new tradition, 3rd edition, Oxford University Press, London Gimpel, Jean (1993) The Cathedral Builders (translated from the French by Michael Russell), London Girouard, Mark (1998) Big Jim: the Life & Work of James Stirling, London Gombrich, E.H. (1960/77) Art and Illusion, Oxford Hays, K. Michael (ed.) (2000) Architecture Theory Since 1968, Cambridge, Mass Isaacs, Jeremy (2000) ‘Wunderkind’ in The Royal Academy Magazine, no. 68, Autumn, London Johnson, Eugene V. & Lewis, Michael J. (1996) The Travel Sketches of Louis I. Kahn, Cambridge, Mass Johnson, N.E. (1975) ‘Light is the Theme’, Fort Worth, Texas Kruft, Hanno-Walter (1994) A History of Architectural Theory from Vitruvius to the Present, London Latour, Alessandra (1991) Louis I. Kahn: writings, lectures & interviews, New York LeCuyer, Annette (1997) ‘Building Bilbao’ in Architectural Review, December Leiviskä, Juha (1999) Juha Leiviskä, Helsinki Libeskind, Daniel (1992) ‘Between the Lines’ in Extension to the 185 Berlin Museum with Jewish Museum Department (ed. Kristin Feireiss), exhibition catalogue, Berlin McLaughlin, Patricia (1991) ‘How am I doing, Corbusier’ in Louis I. -

Vision for M+ Herzog & De Meuron Start Each Project Free Of

Herzog & de Meuron + TFP Farrells Vision for M+ Herzog & de Meuron start each project free of M+ shall be much more than an individual building, but predetermined ideas, guided by curiosity and conscious instead like a small city with entrance gates, gathering naivety. Developed through rational methodologies and places, main avenues and side streets. Movement, of open dialogue, we design projects that respond to the people and objects, shall be conceived horizontally and needs of users and are meaningful to their context. vertically, like Hong Kong itself, to achieve openness and accessibility. M+ has the opportunity and responsibility to lead the architecture and atmosphere of the West Kowloon As a shared platform for the local and global to meet, M+ Cultural District in its development. M+ shall address shall both grow out of and nourish the evolving cultural all of its neighbours with equal consideration whether it community of Hong Kong and include a large distribution be sea or land, city or park, underground or sky, tunnel of education spaces that encourage direct and spontaneous or tower. The responses to each internal and external learning. condition will ultimately shape M+ into its final form. The ability to choose and create one’s own experience We imagine a variety of exhibition possibilities – both could be a key factor that differentiates M+ from previous inside and outdoors – that provide the very specific and incarnations of the big museum, and leads it to become the very flexible by offering a range of spaces and uses not only a global centre of culture, but a common space in that embrace difference and individuality, rather than Hong Kong to generate new perceptions, new phenomena repetition or one-size-fits-all universality. -

Introduction to Modern Literature David Spurr, Fall 2020 11 Nov

Introduction to Modern Literature David Spurr, Fall 2020 11 Nov. Architectural form and representation: Some principles American beginnings of modernism: The Chicago School Louis Sullivan, “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered,” 1896 https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/architecture/4-205-analysis-of-contemporary- architecture-fall-2009/readings/MIT4_205F09_Sullivan.pdf 18 Nov. Organic architecture: Frank Lloyd Wright Wright, “In the Cause of Architecture,” 1908 https://www.architecturalrecord.com/ext/resources/news/2016/01- Jan/InTheCause/Frank-Lloyd-Wright-In-the-Cause-of-Architecture-March- 1908.pdf “Frank Lloyd Wright: American Architect,” Museum of Modern Art, 1940: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2992 Architectural Forum, special issue on Wright, January 1938: https://usmodernist.org/AF/AF-1938-01.pdf 25 Nov. European beginnings of modernism: Walter Gropius Gropius, “Bauhaus Manifesto and Programme,” 1919 http://mariabuszek.com/mariabuszek/kcai/ConstrBau/Readings/GropBau19.p df Gropius, “Principles of Bauhaus Production,” 1926 http://mariabuszek.com/mariabuszek/kcai/ConstrBau/Readings/GropPrdctn.p df Gropius, ”The Theory and Organization of the Bauhaus,” 1923, in Herbert Bayer, Bauhaus 1919-1928, Museum of Modern Art: https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2735_300190238.pdf De Stijl: Gerrit Rietveld Theo van Doesburg, First De Stijl Manifesto, 1918 https://www.readingdesign.org/de-stijl-manifesto Rietveld, “The New Functionalism in Dutch Architecture,“ 1932 https://modernistarchitecture.wordpress.com/2010/10/20/gerrit-rietveld- %E2%80%9Cnew-functionalism-in-dutch-architecture%E2%80%9D-1932/ Machines for Living: Le Corbusier Le Corbusier, “Five Points Towards a New Architecture,” 1926 https://www.spaceintime.eu/docs/corbusier_five_points_toward_new_archit ecture.pdf Le Corbusier, “Towards a New Architecture,” 1927 https://archive.org/details/TowardsANewArchitectureCorbusierLe/page/n91/ mode/2up E1027: Eileen Gray Joseph Rykwert, “Eileen Gray, Design Pioneer,” 1968. -

400 Buildings 230 Architects 6 Geographical Regions 80 Countries a U R P E Or Am S Ica Fr a Ce Ia

400 Buildings 100 single houses┆53 schools┆21 art galleries 66 museums┆7 swimming pools┆2 town halls 230 Architects 52 office buildings┆33 unibersities┆5 international 6 Geographical Regions airports21 libraries┆5 embassies┆30 hotels 5 railway staions 80 Countries 80Architects dings Buil 125 ia As O ce an ZAHA HADID ARCHITECTS//OMA//FUKSAS//ASYMPTOTE ARCHITECTURE//ANDRÉS ia 6 5 PEREA ARCHITECT//SNØHETTA//BERNARD TSCHUMI//COOP HIMMELB(L)AU//FOSTER + B u i ld in g PARTNERS//UNStudio//laN+//KISHO KUROKAWA ARCHITECT AND ASSOCIATES//STEVEN s s t c e 8 it 0 h A c r HOLL ARCHITECTS//JOHN PORTMAN & ASSOCIATES//3DELUXE//TADAO ANDO ARCHITECT r c A h 0 it e 8 c t s & ASSOCIATES//MVRDV//SAUCIER + PERROTTE ARCHITECTES//ACCONCI STUDIO// s g n i d l i DRIENDL*ARCHITECTS//OGRYDZIAK / PRILLINGER ARCHITECTS//URBAN ENVIRONMENTS u B 5 0 ARCHITECTS//ORTLOS SPACE ENGINEERING//MOSHE SAFDIE AND ASSOCIATES INC.// 2 LOMA //JENSEN & SKODVIN ARKITEKTKONTOR AS+ARNE HENRIKSEN ARKITEKTER AS + e p o C-V HØLMEBAKK ARKITEKT//HENN ARCHITEKTEN//GIENCKE & COMPANY//CHETWOODS r u E A ARCHITECTS//AAARCHITECTEN//ABALOS+SENTKIEWICZ ARQUITECTOS//VARIOUS f r i ARCHITECTS//DENTON CORKER MARSHALL//SAMYN AND PARTNERS//ANTOINE PREDOCK// c a FREE Fernando Romero...... 3 5 s B t c u e i t l i d h i n c r g s A 0 8 8 0 s A g r c n i h d i l t i e u c B t s 0 9 a c i r e m A h t r o N S o u t h A m e r i c s t a c e t i h c r A 0 8 1 s 1 g n 5 i d B l i u ISBN 978-978-12585-2-6 7 8 9 7 8 1 Editorial Department of Global Architecture Practice Editorial Department of Global Architecture