L' Abbaye De Maizières

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

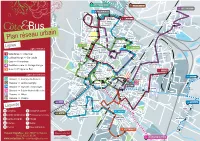

Légende Lignes

ZI de Savigny- lès-Beaune 10 Savigny-lès-Beaune 12 Ladoix-Serrigny 4 Gentilhommière CollègeCollège MongeMonge ForumForum 42 4 Bataillon Mermoz de la Garde 1 Maladières Collège Monge Maladières Clos du Roy Sablière 2 Chilènes Gigny-Ecole Gendarmerie Gigny-Brully Sablière 1 Lac de Gigny Funérarium Savigny 2 Plan réseau urbain Acacias 2 Acacias 1 Cimetière Savigny 1 Route de Dijon Rolin Lignes 3 Primevères Créptilles Lignes urbaines Camping 3 Primevères Hôpital Payot De Lattre Dominicaines Maladières <> Chevrolet Camp Américain 1 Aigue Chorey Collège Monge <> De Gaulle Michel Camping 2 Bon Reon Les Bouleaux Marey 3 Gare <> Primevères Clair Matin Buttes Monument Barbizottes Gentilhommière <> Collège Monge Parc de la aux Morts 4 Bouzaise Colbert Citeaux 1 Gare <> Philippe Le Bon Jardin 5 Bouzaise Anglais 1 Chevrolet ZI de Beaune Square Vignoles des Lions Ferry Lignes interurbaines Collégiale Transco Pétasse Notre Dame Perriaux Lycée Viticole Tribunal 14 Vignoles 10 Beaune <> Savigny-lès-Beaune Hospices Citeaux 2 Bouley 1 2 3 4 5 12 Beaune <> Ladoix-Serrigny MaufouxHôtel Dieu Place Madeleine 10 12 14 16 20 BruottéeBruottés ZI Prévolles Carnot Gare 14 Beaune <> Vignoles / Challanges VeryVéry Celer Laurioz ZA des Bruottés 16 Beaune <> Sainte-Marie-la-Blanche Sécurité sociale Chartreuse Route de 20 Beaune <> Nolay Seurre Dupuis Lac 1 20 Beaune <> Chagny Levées Roupnel 1 20 Nolay Lac 14 Challanges Echaliers Joigneaux Chazeaux TaresRates 11 Marie- St Jacques Légende Noël Roupnel 2 Tulipiers Lac Camping Complexe sportif 2 De Gaulle 20 Chagny TaresRates 22 Centre commercial Etablissement scolaire Cuirassiers Palais des Maranches Centre d’intérêt Hôpital Congrès Cinéma Mairie Piscine Sous-préfecture Ampère 5 Philippe Le Bon Flun Espace Côte&Bus : Gare SNCF de Beaune La Cerisière Tél 03 80 21 85 09 Sainte-Marie-la-Blanche Parc d’entreprises Buffon 16 www.coteetbus.fr - [email protected] de la Porte de Beaune La Saule Rigaud Ru e J. -

Nationalism in the French Revolution of 1789

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Nationalism in the French Revolution of 1789 Kiley Bickford University of Maine - Main Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation Bickford, Kiley, "Nationalism in the French Revolution of 1789" (2014). Honors College. 147. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/147 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIONALISM IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION OF 1789 by Kiley Bickford A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for a Degree with Honors (History) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: Richard Blanke, Professor of History Alexander Grab, Adelaide & Alan Bird Professor of History Angela Haas, Visiting Assistant Professor of History Raymond Pelletier, Associate Professor of French, Emeritus Chris Mares, Director of the Intensive English Institute, Honors College Copyright 2014 by Kiley Bickford All rights reserved. Abstract The French Revolution of 1789 was instrumental in the emergence and growth of modern nationalism, the idea that a state should represent, and serve the interests of, a people, or "nation," that shares a common culture and history and feels as one. But national ideas, often with their source in the otherwise cosmopolitan world of the Enlightenment, were also an important cause of the Revolution itself. The rhetoric and documents of the Revolution demonstrate the importance of national ideas. -

Règlement Du Service De L'assainissement

REGLEMENT DU SERVICE DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT – Communauté d’Agglomération Chalon Val de Bourgogne De plus, le Grand Chalon est responsable, à l’intérieur des agglomérations, des ouvrages majeurs de REGLEMENT DU SERVICE DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT gestion des eaux pluviales sur toutes les communes de la Communauté, hormis Chalon-sur-Saône et Rully, dont le service a été confié, avant la prise de compétence par la Communauté, à des opérateurs Le présent règlement s’applique dans les communes de Barizey, Charrecey, Châtenoy-en-Bresse, privés. Châtenoy-le-Royal, Demigny, Epervans, Farges-les-Chalon, Fontaines, Gergy, Givry, Jambles, La Charmée, Lans, Lessard le National, Lux, Marnay, Oslon, Saint-Ambreuil, Saint-Marcel, Saint-Rémy, Pour les eaux pluviales, en plus des communes citées à la page précédente, le présent Saint-Désert, Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, Saint-Mard-de-Vaux, Sassenay, Sevrey et Varennes-le-Grand règlement s’applique à Champforgeuil, Crissey, Dracy-le-Fort, Fragnes, La Loyère, Mellecey, pour les eaux usées et pluviales Mercurey, Saint Denis de Vaux, Saint Jean de Vaux, Saint Mard de Vaux, Saint Martin sous Pour les eaux pluviales, le présent règlement s’applique dans les communes de Champforgeuil, Montaigu et Virey le Grand. Crissey, Dracy-le-Fort, Fragnes, La Loyère, Mellecey, Mercurey, Saint Denis de Vaux, Saint Jean de Vaux, Saint Mard de Vaux, Saint Martin sous Montaigu et Virey le Grand. L’AUTO-SURVEILLANCE ET LA GARANTIE DE LA QUALITE DES REJETS INFORMATIONS PREALABLES Le suivi de l’évolution de l’état du patrimoine ainsi que l’appréciation de son fonctionnement fait partie intégrante des missions de la Direction de l’Eau et de l’Assainissement. -

Art De Vivre, Belle Campagne, Urbain & Branché

LE BOOK PRO DE LA CÔTE-D’OR Art de vivre, belle campagne, urbain & branché SOMMAIRE LA CÔTE-D’OR PRATIQUE 5 Venir & se déplacer en Côte-d’Or 6 LÉGENDE Thématiques & arguments de vente 7 Au coeur des vignes À chaque besoin, sa réponse 8 Carte des incontournables 10 L’Agenda Une année en Côte-d’Or 12 Nouveau ART DE VIVRE 17 Chez le vigneron À voir, à faire 18 Où manger 21 Groupe Où dormir 23 BELLE CAMPAGNE 29 En ville À voir, à faire 30 Où manger 34 Charme Où dormir 36 Luxe URBAIN & BRANCHÉ 41 À voir, à faire 42 Où manger 44 Campagne chic Où dormir 46 Original RESTONS EN CONTACT 49 À venir en Côte-d’Or 50 À la ferme, locavore Carnet d’adresses 51 3 LA CÔTE-D’OR PRATIQUE 5 Thématiques & arguments de vente 7 À chaque besoin, sa réponse 8 Carte des incontournables 10 L’Agenda Une année en Côte-d’Or 12 ART DE VIVRE 17 À voir, à faire 18 Où manger 21 La Côte-d’Or pratique Où dormir 23 BELLE CAMPAGNE 29 À voir, à faire 30 Où manger 34 Où dormir 36 URBAIN & BRANCHÉ 41 À voir, à faire 42 Où manger 44 Où dormir 46 RESTONS EN CONTACT 49 À venir en Côte-d’Or 50 Carnet d’adresses 51 Côte-d’Or Tourisme © M. Abrial Tourisme Côte-d’Or 5 VENIR & SE DÉPLACER EN CÔTE-D’OR Située au cœur de la Bourgogne à un carrefour européen, la Côte-d’Or est traversée par les axes de transport majeurs comme l’autoroute A6 ou les TGV Paris-Lyon-Marseille et Rhin-Rhône. -

CDC SAINT-AUBIN Homologation 23-10-09

CAHIER DES CHARGES DE L'APPELLATION D'ORIGINE CONTRÔLEE "SAINT-AUBIN" 1/15 CHAPITRE PREMIER I - Nom de l'appellation Seuls peuvent prétendre à l'appellation d’origine contrôlée "Saint-Aubin", initialement reconnue par le décret du 31 juillet 1937, les vins répondant aux dispositions particulières fixées ci-après. II - Dénominations géographiques et mentions complémentaires Le nom de l'appellation peut être complété d’un nom de climat d’origine ou de la mention "premier cru" ou de l’un et de l’autre pour les vins répondant aux conditions de production fixées pour ces mentions dans le présent cahier des charges. Le nom de l’appellation peut être suivi de la dénomination géographique « Côte de Beaune ». III - Couleur et types de produit L’appellation d’origine contrôlée "Saint-Aubin" est réservée aux vins tranquilles blancs ou rouges. La dénomination géographique "Côte de Beaune" est réservée aux vins tranquilles rouges. IV - Aires et zones dans lesquelles différentes opérations sont réalisées 1° - Aire géographique : La récolte des raisins, la vinification, l'élaboration et l'élevage des vins sont assurés sur le territoire de la commune de Saint-Aubin dans le département de la Côte d'Or. 2° - Aire parcellaire délimitée : a) - Les vins sont issus exclusivement des vignes situées dans l’aire parcellaire de production telle qu’approuvée par l'Institut national de l'origine et de la qualité lors des séances du comité national compétent des 9 et 10 février 1977. L’Institut national de l'origine et de la qualité dépose auprès de la mairie de la commune mentionnée au 1°- les documents graphiques établissant les limites parcellaires de l’aire de production ainsi approuvées. -

Liste Des Communes Ou La Presence De Castors Est

LISTE DES COMMUNES OU LA PRESENCE DE CASTORS EST AVEREE L'ABERGEMENT-DE-CUISERY CIEL LAIZY PONTOUX SAUNIERES ALLEREY-SUR-SAONE CLERMAIN LAYS-SUR-LE-DOUBS PRETY SAVIGNY-SUR-GROSNE ALLERIOT CLUNY LESME RANCY SAVIGNY-SUR-SEILLE AMEUGNY CONDAL LOISY RATENELLE LA CELLE-EN-MORVAN ANZY-LE-DUC CORDESSE LONGEPIERRE RIGNY-SUR-ARROUX SOMMANT ARTAIX CORMATIN LOUHANS ROMANECHE-THORINS SORNAY AUTUN CORTAMBERT LOURNAND SAINT-AGNAN SULLY BANTANGES CRECHES-SUR-SAONE LUCENAY-L'EVEQUE SAINT-ALBAIN TAIZE BARNAY CRESSY-SUR-SOMME LUGNY-LES-CHAROLLES SAINT-AUBIN-SUR-LOIRE TAVERNAY BAUGY CRISSEY LUX SAINTE-CECILE THIL-SUR-ARROUX BEY CRONAT MACON SAINTE-CROIX SENOZAN LES BORDES CUISERY MALAY SAINT-DIDIER-EN-BRIONNAIS SERCY LA BOULAYE DAMEREY MALTAT SAINT-DIDIER-SUR-ARROUX SERMESSE BOURBON-LANCY DIGOIN MARCIGNY SAINT-EDMOND SIMANDRE BOURG-LE-COMTE DOMMARTIN-LES-CUISEAUX MARLY-SOUS-ISSY SAINT-FORGEOT TINTRY BOYER DRACY-SAINT-LOUP MARNAY SAINT-GENGOUX-LE-NATIONAL TOULON-SUR-ARROUX BRAGNY-SUR-SAONE ECUELLES MASSILLY SAINT-GERMAIN-DU-PLAIN TOURNUS BRANDON EPERVANS MAZILLE SAINT-JULIEN-DE-CIVRY TRAMBLY BRANGES EPINAC MELAY SAINT-LEGER-DU-BOIS LA TRUCHERE BRAY ETANG-SUR-ARROUX MESSEY-SUR-GROSNE SAINT-LEGER-LES-PARAY UCHIZY BRIENNE FARGES-LES-MACON MESVRES SAINT-LEGER-SOUS-LA-BUSSIERE UXEAU BRION FRETTERANS MONTAGNY-SUR-GROSNE SAINT-LOUP-DE-VARENNES VARENNE-L'ARCONCE BRUAILLES FRONTENARD MONTBELLET SAINT-MARCEL VARENNES-LE-GRAND CHALON-SUR-SAONE FRONTENAUD MONTCEAUX-L'ETOILE SAINT-MARTIN-BELLE-ROCHE VARENNES-LES-MACON CHAMBILLY LA GENETE MONTHELON SAINT-MARTIN-DE-LIXY -

Visites Et Découvertes

Imprimerie Saulieu Imprimerie # FESTI 20 – WILLIAM DEUTCH 4 PARIS Saulieu Imprimerie par modifiée Maquette - Création Rouge Ocre Goumaz, Delphine : graphique Création ARTISANS, PRODUITS DU TERROIR VITTEAUX Tourisme. de Office : photos Crédit • Vente à domicile des grands vins de Bourgogne en CRAFT, LOCAL PRODUCE bouteille, au détail ou en grande quantité suivant demande. Ouvert tous les jours de 10h à 19h ou sur RV # MAISON DE PAYS 1 Thorey-sous-charny Vielmoulin (en cas d’absence, me joindre sur portable). 7 A6 MARTROIS • Exposition-Vente de produits régionaux dans une salle de 270 m2, pour Home sales of great Burgundy wines (bottled), retail or SOMBERNOSOMBERNONN découvrir le savoir-faire de 110 producteurs et artisans bourguignons • large quantities, according to client requirements. Open Réservoir (produits de bouche et artisanat). de Grosbois daily, 10am to 7pm or by appt. (if not there, call mobile phone). 13 • Dégustation sur RV à partir de 10 personnes : Mairey Montberthaut BLANCEY EGUILLY de 5,50 à 10 € par pers. 16, rue Bonaparte • 21320 Thoisy-le-Désert • 09 53 67 41 76 ou 06 75 50 08 58 CIVRY EN 3 8 24 • Ouvert toute l’année : de 10h à 18h (18h30 en [email protected] MONT-ST.JEAN canal de Bourgogn MONTAGNE DIJON juillet - août et décembre) + dimanche et jours 2 10 Lantillière A38 fériés l’après-midi. Entrée libre. 5 BELLENOT # EPICERIE BIOLOGIQUE « CISTELLE NATURE » Sonnotte D108 D970 • Exhibition-Sale of regional produce in large ORGANIC GROCER “CISTELLE NATURE” SOUS POUILLPOUILLYY display area (270 sq. m.). Discover the skills of 110 Ormancey Borde e D108f Burgundian producers and craftsmen (foodstuffs and craftwork). -

Paysage Et Carrières En Saône-Et-Loire DREAL Bourgogne

Paysage et carrières en Saône-et-Loire DREAL Bourgogne Cédric Chardon paysagiste dplg et géographe octobre 2012 PAYSAGE ET CARRIÈRES EN SAÔNE-ET-LOIRE 1 Le pilotage de cette étude a été assuré par la DREAL Bourgogne Service Ressources et Patrimoine Naturel Mission Air Énergies Renouvelables Ressources Minérales 19bis-21 Avenue Voltaire BP 27 805 21 078 DIJON Cedex Cédric Chardon, paysagiste dplg et géographe SIRET : 488 644 063 00031 adresse : 1bis avenue Alphonse Baudin 01000 Bourg-en-Bresse bureau à Lyon : 92 rue Béchevelin 69007 Lyon port : 06 76 41 87 11 fixe : 09 53 24 63 69 fax : 09 58 24 63 69 mail : [email protected] www.atelierchardon.com demande d’autorisation d’utilisation ou de reproduction des photographies et cartographies à demander à la DREAL Bourgogne et à Cédric Chardon paysagiste. PAYSAGE ET CARRIÈRES EN SAÔNE-ET-LOIRE SOMMAIRE CONTEXTE ET OBJE C TIFS 5 1. LES PAYSAGES DE SAÔNE -ET -LOIRE 7 1.1. LES 6 FAMI ll ES DE PAYSAGES DE SAÔNE -ET -LOIRE 9 1.2. LA SENSIBI L ITÉ DES PAYSAGES : cl ÉS DE C OMPRÉHENSION 12 1.3. LES ENTITÉS PAYSAGÈRES DE SAÔNE -ET -LOIRE 18 1.4. LES UNITÉS PAYSAGÈRES DE SAÔNE -ET -LOIRE 19 2. LES C ARRIÈRES DE SAÔNE -ET -LOIRE 63 2.1. ÉTAT DES L IEUX DES C ARRIÈRES EN SAÔNE -ET -LOIRE 64 2.2. L’IMPA C T PAYSAGER DES C ARRIÈRES DE SAÔNE -ET -LOIRE 66 3. LES RE C OMMANDATIONS POUR L A PRISE EN C OMPTE DU PAYSAGE DANS L ES AMÉNAGEMENTS DE C ARRIÈRES 77 3.1. -

RELAIS ASSISTANTS MATERNELS DU DEPARTEMENT DE SAONE-ET-LOIRE Mise À Jour Au 23 Janvier 2020

DIRECTION ENFANCE ET FAMILLES PROTECTION MATERNELLE ET INFANTILE +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ RELAIS ASSISTANTS MATERNELS DU DEPARTEMENT DE SAONE-ET-LOIRE mise à jour au 23 janvier 2020 TERROIRE D'ACTION SOCIALE MONTCEAU LE CREUSOT NOM ET ADRESSE DU ADRESSE DU RELAIS PERMANENCES COUVERTURE GEOGRAPHIQUE AUTUN GESTIONNAIRE Mme Elodie BERGER Mme Rose Hélène CASTILLO Anost – Antully – Autun Saint Pantaléon- Auxy–Barnay - RAM intercommunal lundi de 14 à 18 h Chissey en Morvan – Cordesse - Curgy - Cussy en Morvan Maison de la Petite Enfance Bel Gazou mercredi de 8 à 12 h - Dracy Saint Loup – Igornay - La Celle en Morvan - La AUTUN (CCGAM) 8 Bd Frédéric Latouche - 71400 AUTUN jeudi de 14 à 17 h Grande Verrière - La Petite Verrière – Lucenay l'Évêque – ( 03 85 86 95 33 Monthelon - Reclesne - Roussillon en Morvan - Saint [email protected] Forgeot - Sommant - Tavernay - Mr Luc PIRONNEAU Collonges la Madeleine - Couches - Créot – Dracy les RAM Intercommunal EPINAC Mercredi de 9 à 12 h Couches - Epertully - Épinac - Morlet - Saint Emiland - Centre intercommunal Mairie – Place Charles de Gaulle Saint Gervais sur Couches - Saint Jean de Trézy - Saint d'action sociale 71360 EPINAC ( 03 85 82 99 67 / 07 86 35 15 40 Léger du Bois - Saint Martin de Communes - Saint Maurice Le Grand Autunois Morvan EPINAC / COUCHES (CCGAM) [email protected] les Couches - Saisy - Sully - Tintry - 7 route du Bois de Sapins BP 97 RAM intercommunal -

Résultats Individuels Par Centre

50ème CROSS DEPARTEMENTAL DE SAONE-ET-LOIRE Samedi 06 Février 2016 à DEMIGNY Résultats individuels de l'équipe ANTENNE SUD Catégorie Class Dossard Temps Nom Prénom Né(e) le Masculin Vétéran 1 60 576 0:40:26 VIDAL JEAN-LUC 16/05/1971 62 575 0:40:28 THOUVIGNON DENIS 10/09/1970 2 Personne(s) 2 Personne(s) au total ANTENNE SUD 1/94 50ème CROSS DEPARTEMENTAL DE SAONE-ET-LOIRE Samedi 06 Février 2016 à DEMIGNY Résultats individuels de l'équipe AUTUN Catégorie Class Dossard Temps Nom Prénom Né(e) le Masculin Minime 2 070 0:09:17 MACCORIN NOAH 16/09/2001 87 071 0:12:49 NEVEUX AXEL 05/05/2001 2 Personne(s) Catégorie Class Dossard Temps Nom Prénom Né(e) le Masculin Cadet 8 211 0:22:02 CHIFFLOT NATHAN 22/06/2000 20 213 0:23:00 DOLIVER TOM 03/03/2000 40 220 SCHOTS TANGUY 29/11/2000 58 217 GAUTHIER AYMERIC 14/05/1999 59 212 COMPAGNON ANTHONY 18/06/1999 63 210 BRIEL FLORESTAN 06/03/2000 80 216 GAUTHEY LOUIS 04/06/1999 81 214 DUCHAINE GREGOIRE 31/05/2000 94 215 GATA JONATHAN 24/07/2000 9 Personne(s) Catégorie Class Dossard Temps Nom Prénom Né(e) le Masculin Senior 2 361 0:34:36 CHATELOT ELIE 14/06/1991 9 366 0:37:46 LATTANZI DAVID 31/08/1995 15 363 0:39:19 DEVOUCOUX DENIS 17/09/1982 22 368 0:40:41 RATEAU THIBAUT 22/08/1990 24 362 0:41:39 DE CARLI WILFRIED 27/05/1986 29 365 0:42:20 GUILLERMINET REGIS 05/12/1986 62 367 0:44:42 LORTON THOMAS 11/10/1990 112 360 0:50:19 ARNOULT JONATHAN 25/08/1986 8 Personne(s) Catégorie Class Dossard Temps Nom Prénom Né(e) le Féminine Minime 37 786 0:17:48 PATOUT LUDIVINE 06/10/2001 1 Personne(s) 20 Personne(s) au total -

St Martin En Gatinois

L'église de Saint-Martin-en-Gâtinois maçonnerie du chœur. La voûte en arc brisé porte pierres tombales dont les inscriptions sont également la marque du roman. effacées. L'église est l’une des 57 églises du diocèse placée La nef a été remaniée, probablement en 1790. Dans la nef, près du chœur, une belle pierre sous le vocable de Saint-Martin. Elle a été plafonnée et à la place des baies tombale sous laquelle repose Pierre Midot, mort L'édifice actuel a pris la suite d'une très ancienne romanes, on a percé de larges fenêtres. en 1579. Celui-ci, qui pouvait être le fermier du chapelle construite en 1120 devenue église Dans l'angle nord-ouest de la nef subsiste un seigneur du lieu, a fait don à l'église de terres et paroissiale en 1271. bénitier très ancien qui pourrait être du XIIIe de prés, à charge pour le curé de dire une messe L'architecture générale de l'église rappelle ces siècle. pour le repos de son âme tous les vendredis de édifices construits selon le style roman, en l'année. Une pierre gravée scellée dans le mur Bourgogne, jusqu'à la fin du XIIIe siècle. Statuaire extérieur de l'église côté sud, rappelle cette Les guerres civiles du XVIe siècle et les guerres donation. Dans les chapelles latérales du transept, deux étrangères du XVIIe qui ont ravagé le Val de statues: côté sud, à droite, une Vierge à l'enfant, Vitraux et peintures Saône, ont causé des dégâts importants à l'église côté nord, à gauche, un évêque bénissant, peut- de Saint-Martin. -

The Magisterium of the Faculty of Theology of Paris in the Seventeenth Century

Theological Studies 53 (1992) THE MAGISTERIUM OF THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY OF PARIS IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY JACQUES M. GRES-GAYER Catholic University of America S THEOLOGIANS know well, the term "magisterium" denotes the ex A ercise of teaching authority in the Catholic Church.1 The transfer of this teaching authority from those who had acquired knowledge to those who received power2 was a long, gradual, and complicated pro cess, the history of which has only partially been written. Some sig nificant elements of this history have been overlooked, impairing a full appreciation of one of the most significant semantic shifts in Catholic ecclesiology. One might well ascribe this mutation to the impetus of the Triden tine renewal and the "second Roman centralization" it fostered.3 It would be simplistic, however, to assume that this desire by the hier archy to control better the exposition of doctrine4 was never chal lenged. There were serious resistances that reveal the complexity of the issue, as the case of the Faculty of Theology of Paris during the seventeenth century abundantly shows. 1 F. A. Sullivan, Magisterium (New York: Paulist, 1983) 181-83. 2 Y. Congar, 'Tour une histoire sémantique du terme Magisterium/ Revue des Sci ences philosophiques et théologiques 60 (1976) 85-98; "Bref historique des formes du 'Magistère' et de ses relations avec les docteurs," RSPhTh 60 (1976) 99-112 (also in Droit ancien et structures ecclésiales [London: Variorum Reprints, 1982]; English trans, in Readings in Moral Theology 3: The Magisterium and Morality [New York: Paulist, 1982] 314-31). In Magisterium and Theologians: Historical Perspectives (Chicago Stud ies 17 [1978]), see the remarks of Y.