821213 C(82) 43 (129-215-393).Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Radares 909 Durante La Guerra De Malvinas

BCN 832 9 El Capitán de Navío (R) Néstor Antonio Domínguez egresó de la ENM en 1956 (Promoción 83) y pasó a retiro voluntario en 1983. Estudió Ingeniería Electromecánica (orientación Electrónica) en la Facultad de Ingeniería de la UBA y posee el título de Ingeniero de la Armada. Es estudiante avanzado de la Carre- ra de Filosofía de dicha Universidad. LOS RADARES 909 DURANTE Fue Asesor del Estado Mayor General de la Armada en Materia LA GUERRA DE MALVINAS Satelital; Consejero Especial en Ciencia y Tecnología y Coordinador HMS Sheffield. Académico en Cursos de Capaci- IMAGEN: WWW.BASENAVAL.COM Néstor A. Domínguez tación Universitaria, en Intereses Marítimos y Derecho del Mar y Marítimo, del Centro de Estudios Es- tratégicos de la Armada; y profesor, Postulado de Horner: “La experiencia aumenta directamente investigador y tutor de proyectos de investigación en la Maestría en según la maquinaria destrozada”. Defensa Nacional de la Escuela de Defensa Nacional. Es Académico Fundador y Presi- “La tecnología está dominada por dos tipos de personas: dente de la Academia del Mar y miembro del Grupo de Estudios de • Aquellos que entienden lo que no manejan. Sistemas Integrados en la USAL. • Aquellos que manejan lo que no entienden”. Ha sido miembro de las Comisiones para la Redacción de los Pliegos y De las Leyes de Murphy. (1) la Adjudicación para el concurso in- ternacional por el Sistema Satelital Nacional de Telecomunicaciones por omo lo he expresado en un artículo anterior referido a esta Satélite Nahuel y para la redacción historia (Boletín Nº830), al regreso al país con el destructor inicial del Plan Espacial Nacional. -

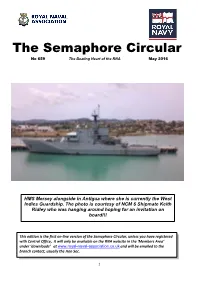

The Semaphore Circular No 659 the Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 659 The Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016 HMS Mersey alongside in Antigua where she is currently the West Indies Guardship. The photo is courtesy of NCM 6 Shipmate Keith Ridley who was hanging around hoping for an invitation on board!!! This edition is the first on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. April Open Day 2. New Insurance Credits 3. Blonde Joke 4. Service Deferred Pensions 5. Guess Where? 6. Donations 7. HMS Raleigh Open Day 8. Finance Corner 9. RN VC Series – T/Lt Thomas Wilkinson 10. Golf Joke 11. Book Review 12. Operation Neptune – Book Review 13. Aussie Trucker and Emu Joke 14. Legion D’Honneur 15. Covenant Fund 16. Coleman/Ansvar Insurance 17. RNPLS and Yard M/Sweepers 18. Ton Class Association Film 19. What’s the difference Joke 20. Naval Interest Groups Escorted Tours 21. RNRMC Donation 22. B of J - Paterdale 23. Smallie Joke 24. Supporting Seafarers Day Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General -

Gunline-Dec-08.Pdf

Gunline Dec08.qxd:Gunline 15/12/08 16:16 Page 1 Gunline - The First Point of Contact Published by the Royal Fleet Auxiliary Service December 2008 www.rfa.mod.uk COMBINED SERVICES CULINARY CHALLENGE 2008 he eighth Combined Services creativity, workmanship, composition TCulinary Challenge took place at and presentation, including taste. A 90% Sandown Park in October and was + score is awarded a gold medal, 75% + yet again an extremely successful a silver medal, 65% + a bronze medal event. Well attended by both and 55% + is awarded a certificate of supporters and competitors; HRH merit. The best in class is awarded a The Countess of Wessex (Patron of further trophy. There were 15 Blue the Craft Guild of Chefs) attended Riband events from which the inter- and presented medals on the last day. service Champions trophy is awarded. The Royal Naval team included This year the RAF won the trophy. competitors from RN, RM, RFA, There was a variety of events, a one Aramark and Sodexho and this year course dish for chefs to prepare, flambé picked up an impressive total of 6 dishes for the stewards to master and gold medals, 10 best in class awards, combination events such as cook and 16 silver medals, 14 bronze medals serve with chef and steward working and 22 certificates of merit. together. It can get very nerve racking The organisation, training, with a camera crew filming your every preparation and co-ordination were move and the audience being very close; demanding and required a huge the junior and novice competitors did amount of time and effort from all. -

198J. M. Thornton Phd.Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Thornton, Joanna Margaret (2015) Government Media Policy during the Falklands War. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/50411/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Government Media Policy during the Falklands War A thesis presented by Joanna Margaret Thornton to the School of History, University of Kent In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History University of Kent Canterbury, Kent January 2015 ©Joanna Thornton All rights reserved 2015 Abstract This study addresses Government media policy throughout the Falklands War of 1982. It considers the effectiveness, and charts the development of, Falklands-related public relations’ policy by departments including, but not limited to, the Ministry of Defence (MoD). -

The Royal Engineers Journal

ISSN 0035-8878 m 0 fl z z m 0 THE id- ROYAL d ENGINEERS r JOURNAL INSTITUTION OF RE OFFICE COPY < DO NOT REMOVE Volume 96 DECEMBER 1982 No. 4 THE COUNCIL OF THE INSTITUTION OF ROYAL ENGINEERS (Established 1875, Incorporated by Royal Charter, 1923) Patron-HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN President Major-General PC Shapland, CB, MBE, MA .......................................................... 1982 Vice-Presidents Brigadier D L G Begbie, OBE, MC, BSc, C Eng, FICE .................................. 1980 Major General G B Sinclair, CBE, FIHE ................................................................ 1980 Elected Members Lieut-Colonel C C Hastings, MBE .................................... 1980 Colonel P E Williams, TD ........ ..................................... 1980 Brigadier D H Bowen, OBE ........... ............................................ 1980 Colonel W MR Addison, BSc ....................................... 1981 ColonelJ G Evans,TD .............................................. 1981 Captain J H Fitzmaurice ............................................. 1981 CaptainA MWright, RE, BSc .......................................................... 1981 ColonelJN Blashford-Snell, MBE ........................................................ 1982 Colonel RC Miall,TD, BSc, FRICS,ACIArb ........................................ 1982 Colonel J HG Stevens, BSc, CEng, FICE ....................................................... 1982 MajorWS Baird, RE ................................................. 1982 Ex-Officio Members Brigadier R A Blomfield, -

Issue 432 April/May 2020

NUMBER APRIL / MAY 432 ! 2020 2210 (Cowley) SQN AIR CADET NEWS: The start of 2020 has seen cadets and staff from 2210 (Cowley) Sqn involved in a number of exciting activities! They attended Thames Valley Wing’s first Multi-Activity Course: it was accommodated on HMS Bristol, a Type 82 destroyer which saw action in the Falklands, and is berthed in Portsmouth. Cadets could choose from courses in leadership, first aid, radio communications, instructional techniques or weapon handling. Cadets from 2210 (Cowley) Sqn also joined others from across Oxfordshire & Berkshire to practise their marksmanship skills by firing the L144A1 target rifle: they were trained to use the weapon safely, then coached during firing to ensure they could accurately & consistently hit a target 25 metres away. Finally 2210 (Cowley) Sqn undertook a 12 Km walk in the countryside to put into practice map reading and navigation skills learnt on normal parade nights. Cadets took it in turn to lead the group, and decide on the route & direction. If you are aged 12 (& in Yr 8) to 19 and interested in joining as a cadet or as a member of staff, please feel free to attend (Mondays & Wednesdays 7.15-9.30 pm, Sandy Lane West) or contact Fg Off O'Riordan on [email protected]. Fg Off Tim O’Riordan (photos © T O’R: all permissions received) THE SCHOOL READINESS PROJECT: GROWING MINDS NEWS FROM LITTLEMORE PLAYGROUP This is a partnership between John Henry Newman Academy, Thank you to the Parish Council for the 2nd part of their grant. Peeple www.peeple.org.uk, Home-Start www.home-start.org.uk, & the We’ve used it to buy much-needed resources: these include Imagination Library imaginationlibrary.com/uk). -

Falklands Survivors

Price £1.00 Black Jack QUARTERLY MAGAZINE SOUTHAMPTON BRANCH WORLD SHIP SOCIETY www.sotonwss.org.uk Issue No: 163 Summer 2012 No longer under threat!!! Plans for the demolition of both iconic 1930s-built gateways to the Western Docks – No 8 seen above on Herbert Walker Avenue and No 10 by the Solent Flour Mills – have now been abandoned after the pair were accorded listed status. Photo by Nigel Robinson Black Jack - 1 2012 Branch Meeting Programme Black Jack - Summer 2012 No.163 June 12th Gosport Ferries – Phil Simons July 10th My First AGM – Monty Beckett Editorial team Mick Lindsay, Nigel Robinson and Editorial Assistant Michael Page. Website – Neil Richardson August 14th Members’ Image Gallery – Our annual competition with slides and Black Jack is the quarterly newsletter for the digital entries Southampton Branch of the World Ship Society. Four editions available for £5 inclusive of postage. September Ocean Liners and Cruise Ships 1905 - th 11 2005 – Doug and Daphne Toogood Branch Meetings Venue: October 9th Blue Funnel Line – John Lillywhite St James Road Methodist Church St James Road November A.G.M. – Plus “The Start of it All”, Shirley 13th Colin Drayson Southampton, SO15 5HE December At Sea in the ‘Fifties – All meetings commence at 19.30 and the meeting 11th Edwin Goodfellow room is to be vacated by 21.30. Meetings are on the second Tuesday of each month. Honorary Branch Secretary Colin Drayson 57 The Drove Commercial St Bitterne Southampton, SO18 6LY 023 8049 0290 Chairman Neil Richardson 109 Stubbington Lane All contributions to BJ either by post, email, floppy disk or Stubbington CD are most welcome. -

United Kingdom Defence Statistics 2010

UNITED KINGDOM DEFENCE STATISTICS 2010 th Published: 29 September 2010 DASA (WDS) Tel: 020-7807-8792 Ministry of Defence Fax: 020-7218-0969 Floor 3 Zone K Mil: 9621 78792 Main Building, Whitehall E-mail: [email protected] London SW1A 2HB Web site: http://www.dasa.mod.uk INTRODUCTION Welcome to the 2010 edition of UK Defence Statistics, the annual statistical compendium published by the Ministry of Defence. Changes to UK Defence Statistics (UKDS) this year include a new section on Defence Inflation and an expanded International Defence section in Chapter 1, the restructuring of the Armed Forces Personnel section in Chapter 2, and a new section on Amputations in Chapter 3. UK Defence Statistics (UKDS) is a National Statistics publication, produced according to the standards of the Official Statistics Code of Practice. However some of the tables in UKDS do not have National Statistics status – some are produced by areas outside of the scope of the Government Statistical Service; some do not yet meet all the quality standards of the Official Statistics Code of Practice; and others have not gone through the required assessment process to be classed as National Statistics. All such tables are clearly marked with explanatory notes. This year UKDS is once again being issued as a web document only, due to financial constraints within the Ministry of Defence. Each table and chapter is available in pdf format which is suitable for printing. There is also a pdf version of the entire publication, and of the UKDS factsheet. We have ceased publication of the UKDS pocket cards this year, since they are of limited value in electronic format. -

RECORD of the MEETING of the LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Held 26Th April 1989

Qll#9 RECORD OF THE MEETING OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL held 26th April 1989 : RECORD OF THE MEETING OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL HELD IN STANLEY ON 26TH APRIL 1989 PRESIDENT His Excellency the Governor, Mr W H Fullerton PRESENT MEMBERS Ex-Officio The Honourable the Chief Executive (Mr R Sampson) The Honourable the Financial Secretary (Mr J H Buckland-James) Elected The Honourable A T Blake (Elected Member for Camp Constituency) The Honourable J E Cheek (Elected member for Stanley Constituency) The Honourable R M Lee (Elected Member for Camp Constituency) The Honourable L G Blake OBE JP (Elected Member for Camp Constituency) The Honourable E M Goss MBE (Elected Member for Camp Constituency) The Honourable T S Betts (Elected Member for Stanley Constituency) PERSONS ENTITLED TO ATTEND The Commander British Forces (Air Vice Marshall D 0 Crwys-Williams) The Attorney General (Mr D G Lang) CLERK Mr P T King PRAYERS Prayers were said by the Reverend J W G Hughes RAF APOLOGIES were received from the Honourable C D Keenleyside and the Honourable Mrs C W Teggart The President Honourable Members, we have two principal items of business before us today: the Legislative Council (Privileges) Bill 1989 and a motion by the Honourable the Chief Executive on Seamount. Before we begin ITd like to extend a warm welcome to both our new Financial Secretary, Mr John Buckland-James, and to the Chief Executive, Mr Ronnie Sampson himself, on the occasion of their first meeting of Legislative Council. It is a pleasure to have them with us. Both I know have impressed us with their enthusiasm and the interest they take in matters pertaining to the Falklands and both bring a wealth of experience which I am sure will be of great value to us all. -

Designer Notes

Designer’s Notes I started work on this game several years ago at the request of Rich Hamilton. I am sure I tried his patience as progress was always slow and sometimes non-existent. While I had helped to playtest Soviet – Afghan Wars and even designed a few scenarios for that game, I had a lot to learn about putting a game together from the ground up. I am still learning as I am sure the play-testers would be happy to confirm. When I was told that the subject of the game would be the Falklands War of 1982, my initial thought was that it would have to be combined with some other conflicts, such as Grenada and Panama to provide enough material for scenarios. However, the more I read about the war, I realized that this was not necessary at all. Unlike any other tactical wargame I am aware of, in Squad Battles Falklands, there are scenarios that cover almost every action above squad level that actually occurred, along with several that did not occur, but might have. This gives the gamer, as well as the designer, a change to fully experience the conflict from beginning to end. It also provides a number of small scenarios utilizing elite troops, such as the SAS, SBS and the Argentine Commandos This game uses the weapon values from Squad Battles Tour of Duty, with only a few changes. HEAT type weapons have a reduced lethality, but the flag that doubles their lethality against vehicles. This was started in Soviet – Afghan Wars and I have retained it. -

Operation in Iraq, Our Diplomatic Efforts Were Concentrated in the UN Process

OPERATIONS IN IRAQ First Reflections IRAQ PUBLISHED JULY 2003 Produced by Director General Corporate Communication Design by Directorate of Corporate Communications DCCS (Media) London IRAQ FIRST REFLECTIONS REPORT Contents Foreword 2 Chapter 1 - Policy Background to the Operation 3 Chapter 2 - Planning and Preparation 4 Chapter 3 - The Campaign 10 Chapter 4 - Equipment Capability & Logistics 22 Chapter 5 - People 28 Chapter 6 - Processes 32 Chapter 7 - After the Conflict 34 Annex A - Military Campaign Objectives 39 Annex B - Chronology 41 Annex C - Deployed Forces and Statistics 43 1 Foreword by the Secretary of State for Defence On 20 March 2003 a US-led coalition, with a substantial contribution from UK forces, began military operations against the Saddam Hussein regime in Iraq. Just 4 weeks later, the regime was removed and most of Iraq was under coalition control. The success of the military campaign owed much to the determination and professionalism of the coalition’s Armed Forces and the civilians who supported them. I regret that, during the course of combat operations and subsequently, a number of Service personnel lost their lives. Their sacrifice will not be forgotten. The UK is playing a full part in the re-building of Iraq through the establishment of conditions for a stable and law-abiding Iraqi government. This process will not be easy after years of repression and neglect by a brutal regime. Our Armed Forces are performing a vital and dangerous role by contributing to the creation of a secure environment so that normal life can be resumed, and by working in support of humanitarian organisations to help the Iraqi people. -

The Semaphore Circular

Published 1st Monday of the Month The Semaphore Circular No 711 The Beating Heart of the RNA July 2021 HMS Victory bottom side up! Next year see’s the ship celebrates being in her dry dock for 100 years and has just opened a walk-way under the hull where you can see the original part of the keel and her innovative design. Shipmates Please Stay Safe If you need assistance call the RNA Helpline on 07542 680082 This edition is the on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec 1 Central Office Contacts Admin 023 9272 3747 [email protected] CEO/General Secretary 023 9272 2983 [email protected] Operations 07889 761934 [email protected] Finance 023 9272 3823 [email protected] Communications 07860 705712 [email protected] Digital Communications [email protected] Fundraising – Special 07926 128754 [email protected] Events Membership Support 023 92723747 [email protected] 07542 680082 [email protected] Welfare Programmes 07591 829416 [email protected] Project Semaphore [email protected] National Advisors National Branch Retention [email protected] and Recruiting Advisor National Welfare Advisor [email protected] National Rules and Bye- [email protected] Laws Advisor National Ceremonial [email protected] Advisor PLEASE NOTE DURING THE CURRENT RESTRICTIONS CENTRAL OFFICE IS CLOSED. PLEASE USE EMAIL OR, IF THE MATTER IS URGENT, THE HELPLINE ON 07542 680082.