Nelson Mandela

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Article the South African Nation

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Article The South African nation Ivor Chipkin In 1996 the South African Labour Bulletin made a startling comparison. It suggested that the movement of trade-unions to invest members' contributions in 'investment companies' resembled models for Afrikaner economic empowerment. InparticularNail (New Africa InvestmentLimited), one of the flagships of Black Economic Empowerment, was compared to Rembrandt, one of the flagships of Afrikaner economic power (SALB 1996). What was being juxtaposed here was African and Afrikaner nationalism. Indeed, it was hinted that they were somehow, even if modestly, similar. What was important was the principle of the comparison: that they could be compared at all! Since then, even if it is not commonplace, it is at least not unusual to hear journalists and others draw similarities between them (see, for example, Heribert Adam in the Weekly Mail & Guardian, April 9,1998). Today it is even possible to hear members of government or the ANC hold Afrikaner nationalism up as a model for Black Economic Empowerment (see Deputy Minister of Finance, MB Mpahlwa 2001). In this vein African and Afrikaner nationalism are beginning to receive comparative treatment in the academic literature as well. Christoph Marx in a recent article discusses continuities between the cultural nationalist ideas of Afrikaner nationalism and those of current day Africanism. -

00 List of Conferred Honorarydegrees.Xlsx

Honorary Degrees Conferred by the CSU 1963-2020 Full Name Degree Campus Date Mildred Jean Ablin Doctor of Humane Letters Bakersfield 6/13/1998 Morton I. Abramowitz Doctor of Laws Stanislaus 5/29/1993 Roberta Achtenberg Doctor of Humane Letters San Marcos 5/19/2017 Jack Acosta Doctor of Humane Letters East Bay 6/12/2010 Abel G. Aganbegyan Doctor of Laws Hayward* 6/15/2002 Yoshie Akiba Doctor of Fine Arts East Bay 6/14/2014 William C. "Bill" Allen Doctor of Humane Letters Northridge 5/22/2014 Isabel Allende Doctor of Humane Letters San Francisco 5/24/2008 Barbara Alpert Doctor of Humane Letters Long Beach 5/28/2021 Raymond Alpert Doctor of Humane Letters Long Beach 5/28/2021 Alfred E. Alquist Doctor of Laws San José 5/24/1997 Abel Coronado Amaya Doctor of Humane Letters Dominguez Hills 5/18/2007 Paul Anka Doctor of Fine Arts Pomona 6/16/2013 Robert Antle Doctor of Humane Letters Monterey Bay 5/19/2007 Alan Armer Doctor of Humane Letters Northridge 5/31/2002 Susan Armstrong Doctor of Science San Luis Obispo 12/5/2020 Ruth Asawa Doctor of Fine Arts San Francisco 5/30/1998 Ronald M. Auen Doctor of Humane Letters San Bernardino 6/13/2013 Sherrie C. Auen Doctor of Humane Letters San Bernardino 6/13/2013 Judith F. Baca Doctor of Fine Arts Northridge 5/18/2018 Robin Baggett Doctor of Laws San Luis Obispo 6/15/2014 Danny J. Bakewell, Sr. Doctor of Humane Letters Dominguez Hills 5/19/2017 Homer P. Balabanis Doctor of Fine Arts Humboldt 6/15/1985 John Baldessari Doctor of Fine Arts San Diego 5/17/2003 David Baltimore Doctor of Science San Luis Obispo 9/28/2001 Raudel J. -

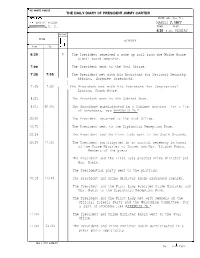

Ihe White House Iashington

HE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDE N T JIMMY CARTER LOCATION DATE (MO., Day, Yr.) IHE WHITE HOUSE MARCH 7, 1977 IASHINGTON, D. C. TIME DAY 6:30 a.m. MONDAY PHONE TIME = 0 E -u ACTIVITY 7 K 2II From To L p! 6:30 R The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. 7:oo The President went to the Oval Office. 7:30 7:35 The President met with his Assistant for National Security Affairs,Zbigniew Brzezinski. 7:45 7:50 I I, The President met with his Assistant for Congressional Liaison, Frank Moore. 8:Ol The President went to the Cabinet Room. 8:Ol 10:05 The President participated in a Cabinet meeting For a list of attendees,see APPENDIX "A." 1O:05 The President returned to the Oval Office. 1O:25 The President went to the Diplomatic Reception Room. 1O:26 The President and the First Lady went to the South Grounds. 1O:26 1l:OO The President participated in an arrival ceremony in honor of the Prime Minister of Israel and Mrs. Yitzhak Rabin. Members of the press The President and the First Lady greeted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin. The Presidential party went to the platform. 10:35 10:45 The President and Prime Minister Rabin exchanged remarks. The President and the First Lady escorted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin to the Diplomatic Reception Room. The President and the First Lady met with members of the Official Israeli Party and the Welcoming Committee. For a list of attendees ,see APPENDIX& "B." 11:oo The President and Prime Minister Rabin went to the Oval Office. -

Potential of the Implementation of Demand-Side Management at the Theunissen-Brandfort Pumps Feeder

POTENTIAL OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF DEMAND-SIDE MANAGEMENT AT THE THEUNISSEN-BRANDFORT PUMPS FEEDER by KHOTSOFALO CLEMENT MOTLOHI Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree MAGISTER TECHNOLOGIAE: ENGINEERING: ELECTRICAL In the Faculty of Engineering, Information & Communication Technology: School of Electrical & Computer Systems Engineering At the Central University of Technology, Free State Supervisor: Mr L Moji, MSc. (Eng) Co- supervisor: Prof. LJ Grobler, PhD (Eng), CEM BLOEMFONTEIN NOVEMBER 2006 i PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com ii DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENT WORK I, KHOTSOFALO CLEMENT MOTLOHI, hereby declare that this research project submitted for the degree MAGISTER TECHNOLOGIAE: ENGINEERING: ELECTRICAL, is my own independent work that has not been submitted before to any institution by me or anyone else as part of any qualification. Only the measured results were physically performed by TSI, under my supervision (refer to Appendix I). _______________________________ _______________________ SIGNATURE OF STUDENT DATE PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com iii Acknowledgement My interest in the energy management study concept actually started while reading Eskom’s journals and technical bulletins about efficient-energy utilisation and its importance. First of all I would like to thank ALMIGHTY GOD for making me believe in MYSELF and giving me courage throughout this study. I would also like to thank the following people for making this study possible. I would like to express my sincere gratitude and respect to both my supervisors Mr L Moji and Prof. LJ Grobler who is an expert and master of the energy utilisation concept and also for both their positive criticism and the encouragement they gave me throughout this study. -

South Africa and the African Renaissance

South Africa and the African Renaissance PETER VALE* AND SIPHO MASEKO On May , immediately prior to the adoption of South Africa’s new con- stitution,Thabo Mbeki, Nelson Mandela’s chosen successor, opened his address to the country’s Constitutional Assembly with the words ‘I am an African!’. In an inclusionary speech, symptomatic of post-apartheid South Africa, Mbeki drew strands of the country’s many histories together. His words evoked great emotion within the assembly chamber, and later throughout the country: across the political spectrum, South Africans strongly associated themselves with the spirit of reconciliation and outreach caught in his words. South Africa’s reunification with the rest of the continent had been a significant sub-narrative within the processes which led to negotiation over the ending of apartheid. That South Africa would become part of the African community was, of course, beyond doubt; what was at issue was both the sequence of events by which this would happen and the conditionalities attached to its happening.The continent’s enthusiasm for the peace process in South Africa was initially uneven: the Organization of African Unity (OAU) summit in June decided to retain sanctions against South Africa although the Nigerian leader, General Ibrahim Babingida, expressed an interest in meet- ing South Africa’s then President, F.W.de Klerk, if such an occasion ‘would help bring about majority rule.’ The political prize attached to uniting South Africa with the rest of the continent explains why South Africa’s outgoing minority government, despite energetic and expensive diplomatic effort, was unable to deliver its own version of South Africa in Africa. -

Remembrance African Activist Archive Project Documenting

Remembrance African Activist Archive Project Documenting Apartheid: 30 Years of Filming South Africa By Peter Davis During April 2004 and beyond we were constantly reminded that this is the tenth anniversary of the first democratic all-race elections in South Africa. I was shocked by the realization that last year also marked the thirtieth anniversary of my first visit to that country, of my first experience with apartheid. After that first trip in 1974 as part of an African tour I was doing for the American NGO, Care, I was to devote a large part of my working life to the anti-apartheid struggle. For those of us who were involved in that struggle, it was such an everyday part of life that it is hard to grasp that there is already a generation out there that does not know the meaning of “apartheid”. The struggle against apartheid took many forms, from protests, strikes, sabotage, defiance, guerrilla warfare within the country to boycotts, bans, United Nations resolutions, rock concerts, and arms and money smuggling and espionage outside. Apartheid, which was institutionalized by the coming to power of the white National Party in 1948, lasted as long as it did, against the condemnation of the world, because it had powerful friends. Chief among these were the United States, which saw a South Africa governed by whites as a useful ally in the Cold War; a Britain whose ruling class had close links with South African capital; and German, French, Israeli and Taiwanese commercial interests that extended even to sales of weapons and nuclear technology to the apartheid regime. -

Mandela at Wits University, South Africa, 1943–19491

UCLA Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies Title “The Black Man in the White Man’s Court”: Mandela at Wits University, South Africa, 1943-1949 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3284d08q Journal Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 39(2) ISSN 0041-5715 Author Ramoupi, Neo Lekgotla Laga Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.5070/F7392031110 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California “The Black Man in the White Man’s Court”: Mandela at Wits University, South Africa, 1943–19491 Neo Lekgotla laga Ramoupi* Figure 1: Nelson Mandela on the roof of Kholvad House in 1953. © Herb Shore, courtesy of Ahmed Kathrada Foundation. * Acknowledgements: I sincerely express gratitude to my former colleague at Robben Island Museum, Dr. Anthea Josias, who at the time was working for Nelson Mandela Foundation for introducing me to the Mandela Foundation and its Director of Archives and Dialogues, Mr. Verne Harris. Both gave me the op- portunity to meet Madiba in person. I am grateful to Ms. Carol Crosley [Carol. [email protected]], Registrar, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, for granting me permission to use archival material from the Wits Archives on the premise that copyright is acknowledged in this publication. I appreciate the kindness from Ms. Elizabeth Nakai Mariam [Elizabeth.Marima@ wits.ac.za ], the Archivist at Wits for liaising with the Wits Registrar for granting usage permission. I am also thankful to The Nelson Mandela Foundation, espe- cially Ms. Sahm Venter [[email protected]] and Ms. Lucia Raadschel- ders, Senior Researcher and Photograph Archivist, respectively, at the Mandela Centre of Memory for bringing to my attention the Wits Archive documents and for giving me access to their sources, including the interview, “Madiba in conver- sation with Richard Stengel, 16 March 1993.” While visiting their offices on 6 Ja- nuary 2016 (The Nelson Mandela Foundation, www.nelsonmandela.org/.). -

World Forestry Congress Flyer

©ICC Durban Investing in people Forestry is an investment in people and, in turn, an investment in sustainable development. This is highlighted by the Congress theme “Forests and People: Investing in a Sustainable Future”, which will explore six sub-themes in more depth: Get involved Forests for socioeconomic development and food security Building resilience with forests From representatives of government or non- Integrating forests and other land uses governmental organizations, private companies, Encouraging product innovation and sustainable trade academia, scientific or professional bodies, forestry Monitoring forests for better decision-making associations and local practitioners, to those who Improving governance by building capacity simply have a personal interest – all are welcome. Registration is required. Discounts on the standard fee are offered to participants from South Africa and other eligible countries, students and retirees, and participants who attend only a few days of the Congress. Defining a We hope you can join us in Durban to help define a future for forests vision for the future of forests and forestry! The Congress will: ©Flickr/ Benh LIEU SONG Strengthen the role of forests and forestry in sustainable development Special events Raise awareness of the major issues facing forests and forestry and propose new forms of technical, scientific Africa and policy actions Business Networking Event Provide a global showcase for the latest developments and innovations Forests and Climate Change Foster new collaborative partnerships -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

The Gordian Knot: Apartheid & the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order, 1960-1970

THE GORDIAN KNOT: APARTHEID & THE UNMAKING OF THE LIBERAL WORLD ORDER, 1960-1970 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Ryan Irwin, B.A., M.A. History ***** The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Peter Hahn Professor Robert McMahon Professor Kevin Boyle Professor Martha van Wyk © 2010 by Ryan Irwin All rights reserved. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the apartheid debate from an international perspective. Positioned at the methodological intersection of intellectual and diplomatic history, it examines how, where, and why African nationalists, Afrikaner nationalists, and American liberals contested South Africa’s place in the global community in the 1960s. It uses this fight to explore the contradictions of international politics in the decade after second-wave decolonization. The apartheid debate was never at the center of global affairs in this period, but it rallied international opinions in ways that attached particular meanings to concepts of development, order, justice, and freedom. As such, the debate about South Africa provides a microcosm of the larger postcolonial moment, exposing the deep-seated differences between politicians and policymakers in the First and Third Worlds, as well as the paradoxical nature of change in the late twentieth century. This dissertation tells three interlocking stories. First, it charts the rise and fall of African nationalism. For a brief yet important moment in the early and mid-1960s, African nationalists felt genuinely that they could remake global norms in Africa’s image and abolish the ideology of white supremacy through U.N. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Nelson Mandela and His Colleagues in the Rivonia Trial

South Africa: The Prisoners, The Banned and the Banished: Nelson Mandela and his colleagues in the Rivonia trial http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1969_08 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org South Africa: The Prisoners, The Banned and the Banished: Nelson Mandela and his colleagues in the Rivonia trial Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 13/69 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid Publisher Department of Political and Security Council Affairs Date 1969-10-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1969 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description Note.