MLB Pitcher Re-Files Lawsuit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Game Information

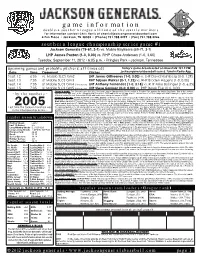

game information double-a southern league affiliate of the seattle mariners For Information contact Chris Harris at [email protected] 4 Fun Place • Jackson, TN 38305 • (Phone) 731.988.5299 • (Fax) 731.988.5246 southern league championship series game #1 Jackson Generals (79-61, 3-1) vs. Mobile BayBears (69-71, 3-1) LHP James Paxton (1-0, 0.00) vs. RHP Chase Anderson (1-0, 3.60) Tuesday, September 11, 2012 • 6:05 p.m. • Pringles Park • Jackson, Tennessee upcoming games and probable pitchers: all times cdt Today’s game broadcasted on NewsTalk 101.5 FM, Date Time Opponent Pitcher jacksongeneralsbaseball.com & TuneIn Radio App. Sept. 12 6:05 vs. Mobile SLCS Gm2 LHP James Gillheeney (1-0, 3.00) vs. LHP David Holmberg (0-0, 1.29) Sept. 13 7:05 at Mobile SLCS Gm3 RHP Taijuan Walker (0-1, 1.23) vs. RHP Braden Hagens (1-0, 0.00) Sept. 14 7:05 at Mobile SLCS Gm4 (if necessary) LHP Anthony Fernandez (1-0, 3.18) vs. RHP Mike Bolsinger (1-0, 6.35) Sept. 15 7:05 at Mobile SLCS Gm5 (if necessary) LHP Steve Garrison (0-0, 0.00) vs. RHP Derek Eitel (0-0, 0.00) TODAY’S GAME: The Generals open the 2012 Southern League Championship Series tonight at Pringles Park against the Mobile BayBears. This is the Jackson franchise’s first apperance in the Championship Series since 2005 and fourth overall appearance. Jackson won 6 of 10 meetings with Mobile during the regular season. - by the numbers - Mobile is looking for their 2nd straight SL title and fourth since joining the league in 19997. -

Arizona Diamondbacks 2015 Spring Training Game Notes

ARIZONA DIAMONDBACKS 2015 SPRING TRAINING GAME NOTES dbacks.com losdbacks.com @Dbacks @LosDbacks facebook.com/D-backs Salt River Fields at Talking Stick 7555 N. Pima Road, Scottsdale, Ariz., 85258 ARIZONA DIAMONDBACKS (2-1) @ SEATTLE MARINERS (2-1) PRESS.DBACKSMEDIA.COM Saturday, March 7, 2015 ♦ Peoria Sports Complex ♦ Peoria, Ariz. ♦ 1:05 p.m. ♦Daily content includes media guides, game notes, statistical reports, lineups, Game No. 4 ♦ Road Game No. 2 ♦ Home Record: 1-1 ♦ Road Record: 1-0 press releases, etc.…please contact a D-backs’ Communications staff mem- RHP Josh Collmenter (NR) vs. RHP Hisashi Iwakuma (NR) ber for the login/password. Arizona Sports 98.7 FM 2015 D-BACKS SPRING SCHEDULE (2-1) DIAMOND-FACTS D-BACKS WEARING “KAYLA” PATCH THIS WEEK WINNING LOSING DATE OPP RESULT REC. PITCHER PITCHER ATT. ♦Arizona is in its 18th Cactus League season (fi fth in ♦D-backs are wearing a black patch with “KAYLA” 3/3 Arizona State W, 4-0 - Schugel Graybill 6,655 the Valley)…Tucson served as the club’s headquar- written on the sleeve in memory of Prescott resi- 3/4 @ COL W, 6-2 1-0 Blair (R, 1-0) Laffey (R, 0-1) 6,780 ters from 1998-2010. dent Kayla Mueller, a human rights activist who 3/5 COL W, 4-3 2-0 Nuño (R, 1-0) Butler (R, 0-1) 7,595 ♦D-backs are 2-1 this spring and 284-267-17 all-time passed away last month while being held captive by 3/6 OAK L, 2-7 2-1 Graveman (1-0) Ray (0-1) 10,726 in spring…in 2014, the D-backs went 12-13-3. -

The Astros' Sign-Stealing Scandal

The Astros’ Sign-Stealing Scandal Major League Baseball (MLB) fosters an extremely competitive environment. Tens of millions of dollars in salary (and endorsements) can hang in the balance, depending on whether a player performs well or poorly. Likewise, hundreds of millions of dollars of value are at stake for the owners as teams vie for World Series glory. Plus, fans, players and owners just want their team to win. And everyone hates to lose! It is no surprise, then, that the history of big-time baseball is dotted with cheating scandals ranging from the Black Sox scandal of 1919 (“Say it ain’t so, Joe!”), to Gaylord Perry’s spitter, to the corked bats of Albert Belle and Sammy Sosa, to the widespread use of performance enhancing drugs (PEDs) in the 1990s and early 2000s. Now, the Houston Astros have joined this inglorious list. Catchers signal to pitchers which type of pitch to throw, typically by holding down a certain number of fingers on their non-gloved hand between their legs as they crouch behind the plate. It is typically not as simple as just one finger for a fastball and two for a curve, but not a lot more complicated than that. In September 2016, an Astros intern named Derek Vigoa gave a PowerPoint presentation to general manager Jeff Luhnow that featured an Excel-based application that was programmed with an algorithm. The algorithm was designed to (and could) decode the pitching signs that opposing teams’ catchers flashed to their pitchers. The Astros called it “Codebreaker.” One Astros employee referred to the sign- stealing system that evolved as the “dark arts.”1 MLB rules allowed a runner standing on second base to steal signs and relay them to the batter, but the MLB rules strictly forbade using electronic means to decipher signs. -

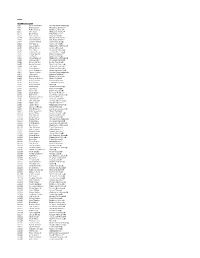

2014 Starting Pitchers Fatigue Ratings GS BF BF

2014 Starting Pitchers Fatigue Ratings GS BF BF RATING Chase Anderson ARI 21 486 23 Bronson Arroyo ARI 14 357 26 Mike Bolsinger ARI 9 221 25 Trevor Cahill ARI 17 397 23 Andrew Chafin* ARI 3 60 20 Josh Collmenter ARI 28 683 24 Randall Delgado ARI 4 78 20 Wade Miley* ARI 33 866 26 Zeke Spruill ARI 1 29 29 Gavin Floyd ATL 9 229 25 David Hale ATL 6 138 23 Aaron Harang ATL 33 876 27 Mike Minor* ATL 25 637 25 Ervin Santana ATL 31 817 26 Julio Teheran ATL 33 884 27 Alex Wood* ATL 24 625 26 Wei-Yin Chen* BAL 31 772 25 Kevin Gausman BAL 20 476 24 Miguel Gonzalez BAL 26 662 25 Ubaldo Jimenez BAL 22 527 24 T.J. McFarland* BAL 1 20 20 Bud Norris BAL 28 687 25 Chris Tillman BAL 34 871 26 Clay Buchholz BOS 28 737 26 Rubby De La Rosa BOS 18 434 24 Anthony Ranaudo BOS 7 170 24 Allen Webster BOS 11 259 24 Brandon Workman BOS 15 353 24 Steven Wright BOS 1 22 22 Jake Arrieta CHC 25 614 25 Dallas Beeler CHC 2 46 23 Kyle Hendricks CHC 13 321 25 Edwin Jackson CHC 27 629 23 Eric Jokisch* CHC 1 20 20 Carlos Villanueva CHC 5 106 21 Tsuyoshi Wada* CHC 13 289 22 Travis Wood* CHC 31 781 25 Chris Bassitt CHW 5 137 27 Scott Carroll CHW 19 482 25 John Danks* CHW 32 855 27 Erik Johnson CHW 5 109 22 Charles Leesman* CHW 1 17 17 Felipe Paulino CHW 4 103 26 Jose Quintana* CHW 32 830 26 2014 Starting Pitchers Fatigue Ratings GS BF BF RATING Andre Rienzo CHW 11 262 24 Chris Sale* CHW 26 685 26 Dylan Axelrod CIN 4 69 17 Homer Bailey CIN 23 604 26 Tony Cingrani* CIN 11 262 24 Daniel Corcino CIN 3 66 22 Johnny Cueto CIN 34 961 28 David Holmberg* CIN 5 110 22 Mat Latos CIN 16 420 26 Mike Leake CIN 33 902 27 Alfredo Simon CIN 32 818 26 Trevor Bauer CLE 26 663 26 Carlos Carrasco CLE 14 360 26 T.J. -

SAN DIEGO PADRES (20-23) at LOS ANGELES DODGERS (25-16) Saturday, May 23, 2015 • 7:10 P.M

SAN DIEGO PADRES (20-23) at LOS ANGELES DODGERS (25-16) Saturday, May 23, 2015 • 7:10 p.m. PT • Dodger Stadium • Los Angeles, CA RHP Ian Kennedy (2-3, 6.75) vs. RHP Mike Bolsinger (2-0, 1.04) Game 44 • Road Game 21 • Mighty 1090 AM • XEMO 860 • FOX Sports San Diego San Diego Padres Communications • 100 Park Ave, San Diego, CA • (619) 795-5000 All Padres game information, including game notes and rosters, is available at http://padrespressbox.com. SO-CAL SERIES: The Padres continue this two-city, six-game Southern California road trip with the second of three PADRES AT A GLANCE tonight at Dodger Stadium after falling in the series opener by a score of 2-1…following tomorrow afternoon’s game the club will head south (31 miles down “The 5”) to Orange County where they will play three interleague games Overall Record: 20-23 against the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim at Angel Stadium (Monday-Wednesday). NL West Standing: 4th (-6.0) Home Record: 11-12 • Following the current road trip, the club will return to Petco Park for a seven-game homestand against the Road Record: 9-11 Pittsburgh Pirates (four games) and New York Mets (three games). Day Record: 6-7 Night Record: 14-16 WILD, WILD WEST: The Padres, to this point in the season, have played 28 of their 43 games, including a stretch of 27 of their fi rst 33 games, against National League West opponents…the club has gone 15-13 this season against Road Trip: 0-1 divisional opponents, including 7-5 in their last 12 divisional games since April 26 vs. -

2016 Topps Updates Checklist

BASE TRADED PLAYERS US6 Chris Herrmann Arizona Diamondbacks® US7 Blaine Boyer Milwaukee Brewers™ US8 Pedro Alvarez Baltimore Orioles® US10 John Jaso Pittsburgh Pirates® US11 Erick Aybar Atlanta Braves™ US12 Matt Szczur Chicago Cubs® US14 Chris Capuano Milwaukee Brewers™ US16 Alexei Ramirez San Diego Padres™ US20 Junichi Tazawa Boston Red Sox® US22 Neil Walker New York Mets® US26 Jose Lobaton Washington Nationals® US28 Alfredo Simon Cincinnati Reds® US32 Juan Uribe Cleveland Indians® US35 Joaquin Benoit Toronto Blue Jays® US36 Yonder Alonso Oakland Athletics™ US37 Jon Niese New York Mets® US41 Mark Melancon Washington Nationals® US42 Andrew Miller Cleveland Indians® US46 Steven Wright Boston Red Sox® US47 Austin Romine New York Yankees® US49 Ivan Nova Pittsburgh Pirates® US51 Steve Pearce Baltimore Orioles® US55 Vince Velasquez Philadelphia Phillies® US60 Daniel Hudson Arizona Diamondbacks® US61 Jed Lowrie Oakland Athletics™ US64 Steve Pearce Baltimore Orioles® US66 Fernando Rodney Miami Marlins® US71 Kelly Johnson New York Mets® US75 Alex Colome Tampa Bay Rays™ US76 Yunel Escobar Angels® US77 Wade Miley Baltimore Orioles® US78 Jay Bruce New York Mets® US80 Aaron Hill Boston Red Sox® US82 Chad Qualls Colorado Rockies™ US83 Bud Norris Los Angeles Dodgers® US87 Asdrubal Cabrera New York Mets® US90 Jake McGee Colorado Rockies™ US91 Dan Jennings Chicago White Sox® US94 Adam Lind Seattle Mariners™ US95 Hector Neris Philadelphia Phillies® US97 Cameron Maybin Detroit Tigers® US98 Mike Bolsinger Los Angeles Dodgers® US100 Andrew Cashner Miami Marlins® -

Cincinnati Reds' Last Glory Year in 1990

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings April 4, 2016 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY 1988-The Reds win on Opening Day for the sixth consecutive season, 5-4, in 12 innings over the Cardinals MLB.COM Glimpse of budding talent as Phils visit Reds By Chad Thornburg / MLB.com | April 2nd, 2016 + 17 COMMENTS Throughout every rebuilding process, there comes a point when a franchise begins to see results. Young prospects break through to the Majors. The lineup starts clicking, the pitching staff finds its groove. Soon, the wins start to accumulate. The Phillies and Reds are hoping 2016 is that year. Both organizations have fallen out of contention in recent years but are in the midst of significant rebuilds. There are many reasons to be optimistic about each club's future, starting with an Opening Day contest in Cincinnati on Monday at 4:10 p.m. ET. Right-hander Jeremy Hellickson will get the start for the Phillies in the opener, while 26- year-old righty Raisel Iglesias goes for the Reds. The Phillies roster that will take the field at Great American Ball Park features some promising youth -- including third baseman Maikel Franco -- with more talent potentially on its way among the Minor League ranks. "This is the most talent we've had in the four years I've been here," said Phillies director of player development Joe Jordan. "We got to see all of our big prospects ... together in big league camp this year, and they all represented themselves very well. There are a lot of good things happening." Opening Day will be a first for new Phillies manager Pete Mackanin, who has managed only on an interim basis prior to this season. -

South Bend Cubs 2018 Media Guide

1 President Joe Hart, Owner Andrew Berlin, Cubs President Theo Epstein and Cubs Senior Vice President Jason McLeod n the first six years of his ownership, affiliate of the Chicago White Sox, the additions of the splash pad, the tiki hut, IAndrew Berlin and his staff have turned team was a hit among locals, drawing an and plenty of new food options across the the South Bend baseball franchise from average of 250,000 fans each season. concourse, Four Winds Field has become a rustbelt dud to Minor League gold South Bend has always been known for a destination for baseball fans from across standard. college sports with the University of Notre the country. Dame. However, professional sports were The story of how the Chairman and CEO new on the scene in the late ‘80s. Looking “We needed to improve everything,” of Berlin Packaging acquired the team has back at the numbers, Hart found that Berlin said. “From the cleanliness, to been well documented, including the date baseball fans in South Bend were present, infrastructure, quality of food, sponsorship, down to the minute (November 11, 2011 at but the ballpark amenities and experiences merchandise… everything needed an 11:11am). But what was the secret ingredi- were not up to par. upgrade.” ent that brought new life into a historical ballpark and baseball team that had lost “We immediately joined every chamber of As the franchise made these massive its identity? commerce within 60 miles of the ballpark,” improvements, the fan base in South Bend Hart said. “As much as I wanted the public grew at a rapid pace. -

LOS ANGELES DODGERS (91-71) at Washington Nationals (95-67) National League Division Series – Game 5 (Series Tied, 2-2) LHP Rich Hill (0-1, 8.31) Vs

LOS ANGELES DODGERS (91-71) at Washington Nationals (95-67) National League Division Series – Game 5 (Series tied, 2-2) LHP Rich Hill (0-1, 8.31) vs. RHP Max Scherzer (0-1, 6.00) Thursday, Oct. 13, 2016 | 8:08 p.m. ET | Nationals Park | Washington, DC TV: FS1 | Radio: AM 570 (Eng.)/KTNQ 1020 AM (Span.)/AM 1540 (Kor.)/ESPN Radio #LALOVESOCTOBER: The Dodgers, champions of the National League MATCHUP vs. NATIONALS West, face the East Division-champion Washington Nationals in a All-Time vs. MON/WAS: LA leads series, 271-194 (14-13 at Nationals Park) decisive Game 5 of their Division Series for the right to face the Cubs All-Time Postseason vs. MON/WAS: 5-4 overall; LA won 1981 NLCS, 3-2 in the NLCS, which opens Saturday in Chicago. 2016: LA won series, 5-1 (2-1 at Nationals Park) The only previous postseason meeting between the Dodgers June 20 @LA: W, 4-1 W: Kershaw L: Petit S: Jansen and the Washington/Montreal franchise ended in a winner- June 21 @LA: W, 3-2 W: Coleman L: Roark S: Jansen take-all Game 5 in the 1981 NLCS, won by Los Angeles, 2-1, June 22 @LA: W, 4-3 W: Hatcher L: Kelley on a ninth-inning home run by Rick Monday. The Dodgers July 19 @WAS: W, 8-4 W: Kazmir L: Lopez lost NLDS Game 5 to the Mets, 3-2, last year at Dodger July 20 @WAS: L, 1-8 W: Gonzalez L: Norris Stadium, but are 4-1 in winner-take-all postseason games July 21 @WAS: W, 6-3 W: Liberatore L: Strasburg S: Jansen since moving to Los Angeles in 1958 (5-4 overall in franchise NLDS G1, Oct. -

Nationals Edge New York Mets 4-3

Sports42 FRIDAY, JULY 24, 2015 Nationals edge New York Mets 4-3 WASHINGTON: Michael Taylor had a tying two-out, the fifth straight time. Todd Frazier extended his post- two-run single in the eighth inning, Danny Espinosa derby surge with three more hits, including a two-run followed with an RBI double and the Washington double in the first inning off Kyle Hendricks (4-5). Joey Nationals rallied from three runs down to beat the Votto added a solo homer off Hendricks, who gave up New York Mets 4-3 on Wednesday. In danger of hav- four runs while facing nine batters in the first inning. ing their lead over the Mets in the NL East cut to one game, Taylor drove in the Nationals’ first run in the PHILLIES 5, RAYS 4, 10 INNINGS fourth with a single off Noah Syndergaard to make it Pinch-hitter Odubel Herrera’s RBI single with two 3-1. After a wild pitch from Bobby Parnell (1-1) put run- outs in the 10th inning lifted Philadelphia to a victory ners on second and third in the eighth, Taylor ripped a over Tampa Bay. The Phillies lost a franchise-record 62 full-count fastball to left to tie it. Taylor then stole sec- games before the All-Star break, but are 5-1 since ond base before Espinosa put Washington in position returning. They swept a three-game set against Miami to take two of three from the Mets and open a three- and took two of three from the Rays to win consecu- game lead in the division. -

BASE US1 Aaron Thompson Minnesota Twins® US2 Wilmer Difo

BASE US1 Aaron Thompson Minnesota Twins® US2 Wilmer Difo Washington Nationals® Rookie US3 Tyler Wilson Baltimore Orioles® Rookie US4 Jean Machi Boston Red Sox® US5 Ryan Vogelsong San Francisco Giants® US6 David DeJesus Angels® US7 Brad Miller Seattle Mariners™ US8 Alex Claudio Texas Rangers® Rookie US9 Shane Greene Detroit Tigers® Future Star US10 Bobby Parnell New York Mets® US11 Evan Gattis Houston Astros® Future Star US12 Travis Ishikawa Pittsburgh Pirates® US13 Tommy Pham St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie US14 Joey Gallo Texas Rangers® Rookie Debut US15 River City Rakers Pittsburgh Pirates® US16 John Axford Colorado Rockies™ US17 Manny Machado Baltimore Orioles® US18 Michael Blazek Milwaukee Brewers™ US19 Erasmo Ramirez Tampa Bay Rays™ US20 Cole Hamels Texas Rangers® US21 High-Voltage Battery San Francisco Giants® US22 Jake Diekman Texas Rangers® US23 Kevin Plawecki New York Mets® Rookie US24 Chris Young New York Yankees® US25 Byron Buxton Minnesota Twins® Rookie US26 Jack Leathersich New York Mets® Rookie US27 Nathan Eovaldi New York Yankees® US28 Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® US29 Ben Paulsen Colorado Rockies™ US30 David Phelps Miami Marlins® US31 Gordon Beckham Chicago White Sox® US32 Blake Swihart Boston Red Sox® Rookie US33 Alex Rodriguez New York Yankees® US34 Matt Andriese Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie US35 Justin Bour Miami Marlins® Rookie US36 Roberto Perez Cleveland Indians® US37 Luis Avilan Los Angeles Dodgers® US38 Michael Lorenzen Cincinnati Reds® Rookie US39 Potent Padres™ San Diego Padres™ US40 Sam Dyson Miami Marlins® US41 Travis Shaw Boston Red Sox® Rookie Combos Allan Dykstra Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie Combos US42 Madison Bumgarner San Francisco Giants® US43 Randall Delgado Arizona Diamondbacks® US44 Tim Cooney St. -

Toronto Blue Jays Make Multiple Trades at Deadline

Toronto Blue Jays make multiple trades at deadline Author : Robert D. Cobb The Toronto Blue Jays were quite busy today as they made multiple deals to help strengthen their pitching staff and bullpen. They ended up acquiring Scott Feldman from the Houston Astros and Francisco Liriano from the Pittsburgh Pirates. They ended up trading Jesse Chavez to the Los Angeles Dodgers for pitcher Mike Bolsinger. In addition to all these deals being done, it was also announced that the Blue Jays would be moving pitcher Aaron Sanchez to the bullpen. Let's look first at the Scott Feldman trade. The Blue Jays ended up trading Scott Feldman for RHP prospect Guadalupe Chavez. Reports were coming out after the trade that the plan with Scott Feldman is to use him out of the bullpen for a majority of the season. One upside to having someone like Scott Feldman is he can be a spot starter for the Blue Jays as they try to make a push towards the playoffs for the second consecutive season. During his time in Houston, Scott Feldman ended up pitching five games as a starter and spent the rest of the time pitching out of the bullpen. The next trade made by the Toronto Blue Jays made came down after the 4 pm deadline. It was reported on several sites that the Blue Jays had acquired Francisco Liriano from the Pittsburgh Pirates for Drew Hutchinson. When Francisco Liriano was sent to Pittsburgh, he had a bit of a revival in his career as he went 35-25 between 2013 to 2015.