Legitimacy on Stage: Discourse and Knowledge in Environmental Review Processes in Northern Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YELLOWKNIFE Map Legend SKI CLUB

FOLK ON 1 THE ROCKS 9 LONG LAKE N’dilo G NWT HIGHWAY No. 4 NWT HIGHWAY No. 3 PROSPECTORS’ TRAIL NWT HIGHWAY No. 3 INGRAHAM TRAIL INGRAHAM YELLOWKNIFE map legend SKI CLUB 2 LATHAM ISLAND Stanton Territorial Hospital 4 15 14 1 1 BACK BAY Fire Department JACKFISH YELLOWKNIFE AIRPORT 2 Police LAKE BACK BAY LOOKOUT TRAIL Yellowknife Airport 11 Boat Launch BOULEVARD CHO DEH 3 5 10 Heritage Site 8 4 2 YELLOWKNIFE BAY Hotel 10 7 Bed & Breakfast 9 3 NWT HIGHWAY No. 4 No. HIGHWAY NWT Gas Station NIVEN LAKE TRAIL JOLIFFE ISLAND OLD AIRPORT ROAD 12 Key Attraction NIVEN LAKE 4 Aurora Viewing 6 FRAME 12 Walking/Hiking Trail LAKE 13 1 Campground 6 5 MCMAHON FRAME LAKE TRAIL 11 Park 4 Water ? 9 5 5 13 48th STREET Ice Road 49th STREET SCHOOL DRAW AVENUE 4 9 ICE ROAD TO DETTAH BORDEN DRIVE 50th STREET City Hall FRANKLIN AVENUE (50th AVE.) 51st STREETF 8 52nd STREET T 6 Visitor Centre REE ST 53rd STREET EL Z 54th STREET 7 IT A Ruth Inch Memorial Pool RANGE LAKE 8 G 2 1 7 2 B Yellowknife Community Arena 10 5 RANGE LAKE TRAIL 11 3 OLD AIRPORT8 ROAD C Yellowknife Curling Club 13 A 3 52nd AVENUE D Multiplex B 6 C E Yellowknife Fieldhouse 7 FORRE ST D F Public Library RI VE 3 G Solid Waste Facility (Dump) DEH CHO BOULEVARD TRAIL FRANKLIN AVENUE (50th AVE.) 12 D A O R E K TIN CAN HILL TRAILS A TAYLOR ROAD DEH CHO BOULEVARD L D washrooms E G CO N N E A RO R A City Hall Visitor Centre, 4807-52 Street D Twist & Shout, 4915 – 50 Street Yellowknife Fieldhouse, 45 Kam Lake Road KAM LAKE ROAD Multiplex, 41 Kam Lake Road Yellowknife Community Arena, 6004 Franklin Ave. -

Checklist of Northwest Territories Government Publications for 2002

CHECKLIST OF NORTHWEST TERRITORIES GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS FOR 2002 Bureau of Statistics 2001 NWT socio-economic scan. May 2001. [78] p. GNWT government-wide measures: 2001. September 2001. 74 p., col. ill. Labour market trends: Northwest Territories - 1999. November 2001. 1 v., ill. Statistics quarterly. Volume 23, no. 2, June 2001. v, 46 p. Volume 23, no. 3, September 2001. v, 46 p. Volume 24, no. 1, March 2002. v, 46 p. Volume 24, no. 2, June 2002. v, 46 p. Education, Culture and Employment Departmental directive for career development across the lifespan. June 2001. 18 leaves. NWT labour force development plan: 2002-2007 … a workable approach. March 2002. 56 p., ill. A plain language audit tool / written by the NWT Literacy Council. 2002. 12 p., ill. Revitalizing, enhancing, and promoting aboriginal languages: strategies for supporting aboriginal languages. [2002]. ii, 64 p., col. ill. Towards excellence : a report on education in the NWT. 2002. 94 p. N.W.T. Tabled Document 69-14(5). Tabled on October 29, 2002. Voices of our youth: stories for Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in honour of the Golden Jubilee from students of the Northwest Territories. 2002. 151 p., col. ill. Write for your reader: a plain language handbook / written by the NWT Literacy Council. 2002. iv, 63 p., ill. Aurora College. Aurora Research Institute Gwich'in ethnobotany: plants used by the Gwich'in for food, medicine, shelter and tools / by Alestine Andre and Alan Fehr. Published and distributed by Gwich'in Social and Cultural Institute and Aurora Research Institute. 2001. 68 p., ill. (some col.) Executive - 2 - Doing our part: the GNWT's response to the social agenda. -

Northern Transportation Conference

November 9 & 10, 2005 Yellowknife, Northwest Territories Post-Conference Report Paul D. Larson, Ph.D. Post-Conference Report Proceedings of the Northern Transportation Conference Paul D. Larson, Ph.D. Professor and Head, Department of Supply Chain Management Director, Transport Institute Asper School of Business University of Manitoba 614 Drake Centre Winnipeg, MB R3T 5V4 phone: 204-474-6054 fax: 204-474-7530 e-mail: [email protected] Dedicated to Douglas E. Larson, a wonderful man and a great Dad. Northern Transportation Conference Table of Contents Executive Summary Page 4 The Conference Page 6 Issues and Stakeholders Page 8 Conference Presentation Summaries Page 10 Session One: Northern Vision, Priorities and Expectations Page 10 Session Two: Transportation Partnerships Page 12 Session Three: Current Northern Transportation Infrastructure Page 14 Luncheon Keynote Address Page 17 Session Four: Air Transportation Challenges Page 17 Session Five: Surface and Marine Transportation Challenges Page 20 Session Six: Pipeline Development Page 23 Session Seven: Climate Change Page 24 Session Eight: Northern Sovereignty and Security Page 27 Northern Transportation Moving Forward: An Action Plan Page 32 References Page 38 Appendix I. Roundtable Discussion Summaries Page 39 Appendix II. Survey Results Page 43 Appendix III. Web Sites Page 52 Yellowknife, Northwest Territories 2 Northern Transportation Conference Appendix IV. Maps Page 55 Appendix V. Conference Program and Participants Page 56 Yellowknife, Northwest Territories 3 Northern Transportation Conference Executive Summary The primary purpose of this report is to propose and outline an action plan for northern transportation in Canada. The action plan follows from the Proceedings of the Northern Transportation Conference, including expert presentations, discussions, roundtable sessions and a survey. -

Accommodations, Services, Outfitters & Operators and Events

Accommodations, Services, Outfitters & Operators and Events Nunavut Tourism is a not-for-profit membership based industry association representing Canada's newest and largest territory; our members provide the finest and safest experiences in Nunavut. Your journey to the Canadian Arctic begins right here. The following listing will help you plan your trip to Nunavut – find the right hotel, outfitter or travel service for your adventure! Within each section, services are listed alphabetically and categorized by community when applicable; for a snapshot of tourism operators, outfitters and related businesses skip to centre for an at-a-glance list. Also, be sure to check out the Community Events Listing on the last page to see what’s happening around Nunavut throughout the year! Did you know about our airline discounts? Talk to Nunavut Tourism today to learn how you can save. Accommodations Nunamiut Lodge Green Row Executive Suites P.O. Box 369, Baker Lake, NU X0C 0A0 P.O. Box 1052, Cambridge Bay, NU X0B 0C0 Arviat T: 867.793.2512 T: 867.983.3456 Katimavik Suites (Arviat) F: 867.793.2505 F: 867.983.3444 P.O. Box 420, Arviat, NU X0C 0E0 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] T: 867.857.2752 www.nunamiutlodgehotel.ca www.greenrow.ca F: 867.857.2972 Welcome to the Nunamiut Lodge Hotel in Baker Our 2 Bedroom suites are similar to a small apart - E: [email protected] Lake! 100% Inuit Owned. At the Nunamiut ment and offer you the same comforts as being in www.katimaviksuites.com Lodge Hotel, enjoy our northern hospitality in a your own home. -

Meeting&Conferenceplan

MEETING&CONFERENCEPLANNER2011 1.800.661.0788SPECTACULARNWT.COM VAN BRUGGEN | CTC Over 600 quality rooms for your next conference in Yellowknife. ARNICA INN CAPITAL SUITES CHATEAU NOVA HOTEL COAST FRASER TOWER www.arnicainn.com www.capitalsuites.ca AND SUITES SUITE HOTEL 43 rooms 53 one and two www.chateaunova.com www.coasthotels.com bedroom suites 80 rooms including suites 58 suites EXPLORER HOTEL NOVA COURT SUPER 8 YELLOWKNIFE INN www.explorerhotel.ca www.scpl.com www.super8yellowknife.com www.yellowknifeinn.com 187 rooms 54 rooms 66 rooms 129 rooms The Mark of Quality Accommodations The Mark of Quality Accommodations in Yellowknife. in Yellowknife 2 FOllOw us for uPDATEs at Twitter.com/spectacularnwT ENODAH WILDERNESS LTD. 02. The Fish (eating and catching!) CTC | NWT TOURISM TERRY PARKER | NWT TOURISM 01. The Northern Lights 03. Amazing Wildlife 04. The Midnight Sun GEORGE FISCHER | NWT TOURISM TERRY PARKER | NWT TOURISM 05. The Cultural Events 06. Outdoor Adventures DAVE BROSHA | NWT TOURISM DAVE BROSHA | NWT TOURISM DAVE BROSHA | NWT TOURISM DAVE BROSHA | NWT TOURISM 07. The Modern Facilities 08. Forged Friendships 09. All That You Learned 10. Endless Smiles NOrTHwEsT TERRITOrIEs TOURIsM | 2011 CONFErENCE & MEETING PlANNEr | 1.800.661.0788 | sPECTACULArNwT.COM 3 4 FOllOw us for uPDATEs at Twitter.com/spectacularnwT WE’RE HERETO HELP Planning your next conference or event in the Northwest conference or event. Your options are endless: from day trips by Territories is simply one of the best decisions you’ll boat or air, to short walking excursions to lakeside lodges that ever make. Not only will you have chosen a unique and cater to your every need. -

City of Yellowknife Visitor

IL) RA T AM 16 H RA G 10 IN ( 5 3 . M I O TC N H 4 Y EL A L W D R. H 2 IG H Back .T CITY OF A .W RC N WAY NO. 3 H N.W.T HIGH IB Bay 3 AL D S T. 1 YELLOWKNIFE 15 . D R EY Long IL W 4 VISITOR MAP 9 . D . 13 R R 3 Lake E D IN C M ID C A 12 A A H A A 6 R R 9 R G G D N UN CL I UB RD. 8 B RIS TO 2 L C 6 R 11 T. BLACKB ERG D ST. R. 5 . R BRINTNELL D D B AL R N . IS I O ST TO L D Y TI ILI C 4 RR L O. 3 T M E AV Y N O E 3 Yellowknife B E WA IL E . IGH IL CH .T H T A N.W T I 5 IL WEAVER DR. 18 T Bay 3 ORAH A N. E S L ST. Y OT’ MCMILLAN K PIL 1 SI TILI KEMELLI TILI 10 ILI 7 A T . 11YE D 8 .) T O IK R E S T S R V 11 T NE A S R 11 O S U 0 1 . H T 5 N ( I Jackfish R . D E E K 3 D R V L A 13 C . I N A IN L D O 4 K S N I A Lake 1 R FR R Back O . -

NEWS to a Better Future for Our North

NAPEG Vision Recognition as a trusted authority contributing NAPEG NEWS to a better future for our North. Volume 6, Issue 5 Friday, September 27, 2019 DESK OF EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR / REGISTRAR Call for NAPEG Award Nominations Do you have a project that should be recognized for its Do you have suggestions for speakers for the Annual excellence? Do you know an engineer or geoscientist Professional Development Symposium? Is there a topic who deserves recognition? Is there a significant project that would be of interest to you? You can find a form for in Nunavut or Northwest Territories that should be Expression of Interest on the NAPEG website. recognized and awarded? The Professional Development Symposium takes place If so, please consider submitting a nomination for a over two days and generally includes at least one local NAPEG Award. You can find a nomination form on the tour. There is no increase in the fee to attend in 2020 NAPEG Website or you could call the NAPEG Office and you’ll be earning Professional Development Hours and we will send you a copy of the nomination form. to help with your mandatory reporting. We want to make the events both relevant and enjoyable. To see who has been recognized in the past, you can review the 2019 Annual Report. It shows both the 2019 Immediately following the NAPEG AGM, there is an recipients and past award recipients. AGM for the NAPEG Education Foundation. To read more about the Foundation, you can review the 2019 We need your help to make the 2020 Awards Banquet Annual Report for the Foundation. -

2018 Visitors Guide Travel Tips ✱ Maps ✱ Activities

FREE 2018 VISITORS GUIDE TRAVEL TIPS ✱ MAPS ✱ ACTIVITIES The City of Yellowknife WELCOMES YOU! Discover Yellowknife is a cooperative effort from our own City staff and the team at Up Here Publishing. Yellowknife’s unique location is the perfect start for an unforgettable experience. Stay a weekend, a week or a month, and discover our vibrant capital city on the shores on Great Slave Lake. Many year-round adventures are to be had in Yellowknife and no matter the season, our parks and trails are worth a visit. Hike around the beautiful Frame Lake for a skyline view of downtown Yellowknife. During the winter, head out onto the Great Slave Lake ice road or visit the Snow Castle and Long John Jamboree. Take the kids tobogganing or exploring in one of our many playgrounds around the city. Between June and September, join the locals for a picnic at Somba K’e Civic Plaza as they gather for the weekly Yellowknife Farmer’s Market. In Yellowknife, the wilderness is only five minutes away. Whether you prefer a stroll around downtown, a self-guided tour in Old Town, viewing the aurora, dogsledding, fishing, paddling or hiking in the wilderness - I am sure you will discover a spectacular Connect with the MACKENZIE/NWTT JAMES City of Yellowknife on experience of your choosing! Welcome to Our Yellowknife! Mayor Mark Heyck yellowknife.ca [email protected] CONTENTS 8 INTRODUCTION 44 WITH THE KIDS A quick look at our city, from its Family fun and adventure awaits. history to busting common myths. 48 FOOD & DRINK 12 GETTING HERE From high-end cuisine to Travelling to (and within) the city? irresistible food trucks and diner classics. -

Adobe Photoshop

Message from the Chair ................................................................................................................................................ 1 CEO’s Report .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 In Memoriam ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Vision, Mission and Background .................................................................................................................................... 4 Marketing & Communications ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 5 FAM Tours ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Trade Shows .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Advertising & Other Events ........................................................................................................................... 9 Recreational Sport Fishing .......................................................................................................................................... -

Frobisher Inn & Explorer Hotel

Frobisher Inn & Explorer Hotel www.nunastar.com 02 Experience the warmth of Canada’s arctic hotels COMPANY FOCUS CB THE FROBISHER INN AND EXPLORER HotEL Experience the warmth of Canada’s arctic hotels 4 HOSPITALITY The Frobisher Inn and Explorer Hotel A lot of times when people think about the Arctic, visions of polar bears, igloos and snow-covered barren land ensue. Those images aren’t necessarily inaccurate, but they don’t represent all that goes on in the Great White North. The Arctic is Canada’s last frontier and, truth be told, things are heating up. Just ask Rainer Launhardt, Vice President of Hotels for Nunastar Properties. “WHEN NunaVut BEcamE the newest Canadian territory in 1999, there was a lot of activity and construction in Iqaluit,” says Launhardt. “The government was establishing itself, the city needed infrastructure and a lot of people were visiting for different reasons. More than 10 years later, people are still coming and going, and the city of Iqaluit is expanding every year.” The influx of visitors in the last decade has created a need for more hospitality. And that’s where The Frobisher Inn comes into play, because visiting the north doesn’t mean roughing it. Located at the centre of Nunavut’s capital city, The Frobisher Inn is the largest hotel in the eastern Arctic—which was recently expanded to house 95 rooms. With unparalleled full-service, the Frobisher Inn is the hotel destination in one of Canada’s fastest growing cities. HOSPITALITY The Frobisher Inn and Explorer Hotel 6 HOSPITALITY The Frobisher Inn and Explorer Hotel Named after British explorer Sir Martin Fro- “This is a hotel with a flavour of the north,” says bisher, who landed on Baffin Island in search of Launhardt. -

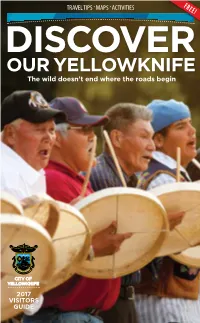

OUR YELLOWKNIFE the Wild Doesn’T End Where the Roads Begin

TRAVEL TIPS • MAPS • ACTIVITIES FREE! DISCOVER OUR YELLOWKNIFE The wild doesn’t end where the roads begin 2017 VISITORS GUIDE OLD TOWN. PILOT’S MONUMENT. WILDCAT CAfÉ. LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. FRAME LAKE TRAIL. SEE THEM ALL. If you’re visiting Yellowknife, stop by the Northern Frontier Visitors Centre Outcrop is offering visitors free use of a fleet of sturdy one-speed bicycles for touring anywhere within the city limits, any day of the week from early June until late September. The Quarry Restaurant, located at the Chateau Nova Yellowknife, delivers food and quality nothing short of exceptional. This modern steakhouse-themed restaurant is opened for breakfast, lunch and dinner and offers a large menu at really great prices. NORTHERN FRONTIER Our Quarry Lounge provides the perfect atmosphere to meet for drinks, enjoy nightly food specials or finish the day VISITORS CENTRE with a nice glass of vino. 867.873.4262 visityellowknife.com CLIENT: Client Name VERSION: A REVISION: 1 DATE: Dec / 22 / 16 TIME: DOCKET #: 0000-A000 SIZE: 5.25” x 8.5” (with full bleed 0.125”) (Full page) COLOUR: CMYK DESIGNER: BC PUBLICATION: Visitor’s Guide, Year UP HERE PUBLISHING LTD. / Suite 800 / 4920-52 Street / Yellowknife / Northwest Territories / Canada / X1A 3T1 / T. 867-766-6710 / F. 867-873-9876 / www.uphere.ca The City of Yellowknife WELCOMES YOU! Discover Yellowknife is a cooperative effort from our own City staff, the friendly tourism staff at the Northern Fron- tier Visitor Centre and the team at Up Here Publishing. Yellowknife’s unique location is the perfect start for an unforgettable experience. -

Link to the Program

The Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada’s 35th Annual Conference 1 La Société pour l’Étude de l’Architecture au Canada 35e Congrès Annuel Yellowknife, Northwest Territories / Territoires du Nord-Ouest 28 Juin-1 Juillet 2008 / June 28-July 1st 2008, Explorer Hotel CONFERENCE PROGRAM / PROGRAMME DU CONGRÈS FRIDAY JUNE 27 / VENDREDI 28 JUIN 18:00- Registration and Reception / Inscription et reception, Explorer Hotel 21:00 SATURDAY JUNE 28 / SAMEDI 28 JUIN 8:00 Registration / Inscription 9:00 Welcome, Andrew Waldron, President SSAC / Remarque préliminare, Andrew Waldron, président de la SÉAC 9:10 Drum Ceremony, N’Dilo drummers / Cérémonie du tambour, N’Dilo batteurs 9:20 Commissioner of the Northwest Territories Address / Remarque préliminaire du Commissaire des Territories du Nord-Ouest 9:30 Mayor’s Address / Remarque préliminare du maire de Yellowknife 9:40 Presentation of the Phyllis Lambert Prize / Présentation du Prix Phyllis Lambert 10:00 Book Launch / Lancement du livre: Peter Coffman, Newfoundland Gothic, l’Institut du patrimoine, UQAM 10:30 Coffee Break / pause-café SESSION 1 / SÉANCE 1 REGIONALISM / EXPRESSIONS RÉGIONALES MODERATOR: ANDREW WALDRON 11:00 Kelly Crossman: Rethinking Prairie Regionalism 11:30 David Monteyne: Questioning Regionalism 12:00 Lunch Break / pause déjeuner SESSION 2 / SÉANCE 2 THE WEST COAST / LA CÔTE OUEST MODERATOR: TBA / AC 1:00 Barry Magrill: Village and Town Churches in British Columbia and the Yukon 1:30 Norman Shields: Division of Space in Chee Kung Tong Buildings: The Example of Barkerville,