" Mum STATE UNIVERSITY * F Wllliam ELUOT THOMPSON 1.976

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News, Notes, & Correspondence

News, Notes, & Correspondence The Theatre of E. E. Cummings Published In the News, Notes & Correspondence section of Spring 18, we re- ported that a new edition of The Theatre of E. E. Cummings was in the works, and—behold!—the book appeared on schedule at the beginning of 2013. This book, which contains the plays Him, Anthropos, and Santa Claus, along with the ballet Tom, provides readers with a handy edition of Cummings’ theatre works. The book also has an afterword by Norman Friedman, “E. E. Cummings and the Theatre,” which we printed in Spring 18 (94-108). The Thickness of the Coin In February, 2012 we received a card from Zelda and Norman Fried- man. They wrote: We are okay and want to tell you that the older we get the more skillful and wise E. E. Cummings becomes. Zelda has been trying to locate the line “love makes the little thickness of the coin” and came upon it accidentally in “hate blows a bubble of despair into” across the page in Complete Poems from “love is more thicker than forget”—the poem where she thought it might be. The Cummings-Clarke Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society *In October 2012, Peter Steinberg of the Massachusetts Historical Society wrote to inform us that some of the Cummings-Clarke family papers con- taining “some materials by E. E. Cummings” had “recently been processed and made available for research.” Peter sent us the following “link to the finding aid / collection guide in hopes that you or your society members might be interested in learning about [the papers and] visiting the MHS”: http://www.masshist.org/findingaids/doc.cfm?fa=fa0367. -

E. E. Cummings

Center for the Book at the New Hampshire State Library BIBLIOGRAPHY January 2007 e. e. cummings Poetry 1 x 1. Holt, 1944; reprinted edited, afterword, by George James Firmage. Liveright, 2002. 1/20. Roger Roughton, 1936. 100 Selected Poems. Grove, 1958. 22 and 50 Poems. Edited by George James Firmage. Liveright, 2001. 50 Poems. Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1940. 73 Poems. Harcourt, 1963. 95 Poems. Harcourt, 1958, reprinted edited by George James Firmage. Liveright, 2002. &. privately printed, 1925. (Contributor) Peter Neagoe, editor, Americans Abroad: An Anthology. Servire, 1932. Another E. E. Cummings. selected, introduced by Richard Kostelanetz, Liveright, 1998. (Chaire). Liveright, 1979. (Contributor) Nancy Cummings De Forzet. Charon's Daughter: A Passion of Identity. Liveright, 1977. Christmas Tree. American Book Bindery, 1928. Collected Poems. Harcourt, 1938. Complete Poems, 19101962. Granada, 1982. Complete Poems, 19231962. two volumes, MacGibbon & Kee, 1968; revised edition published in one volume as Complete Poems, 19131962. Harcourt, 1972. (Contributor) Eight Harvard Poets. L. J. Gomme, 1917. Etcetera: The Unpublished Poems of E. E. Cummings. Edited by Firmage and Richard S. Kennedy, Liveright, 1984. Hist Whist and Other Poems for Children. Edited by Firmage, Liveright, 1983. NH Center for the Book BIBLIOGRAPHY p. 2 of 4 e.e. cummings (January. 2007) In JustSpring. Little, Brown, 1988. is 5. Boni & Liveright, 1926; reprinted, Liveright, 1985. Love Is Most Mad and Moonly. AddisonWesley, 1978. May I Feel Said He: Poem. Paintings by Marc Chagall, Welcome Enterprises, 1995. No Thanks. Golden Eagle Press, 1935; reprinted, Liveright, 1978. Poems, 19051962. edited by Firmage, Marchim Press, 1973. Poems, 19231954. -

Harold Bloom

E.E. Cummings CURRENTLY AVAILABLE BLOOM’S MAJOR POETS Maya Angelou Elizabeth Bishop William Blake Gwendolyn Brooks Robert Browning Geoffrey Chaucer Samuel Taylor Coleridge Hart Crane E.E. Cummings Dante Emily Dickinson John Donne H.D. T. S. Eliot Robert Frost Seamus Heaney A.E. Housman Homer Langston Hughes John Keats John Milton Sylvia Plath Edgar Allan Poe Poets of World War I Shakespeare’s Poems & Sonnets Percy Shelley Wallace Stevens Mark Strand Alfred, Lord Tennyson Walt Whitman William Carlos Williams William Wordsworth William Butler Yeats E.E. Cummings © 2003 by Chelsea House Publishers, a subsidiary of Haights Cross Communications. Introduction © 2003 by Harold Bloom. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America. First Printing 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data E. E. Cummings / edited and with an introduction by Harold Bloom. p. cm.— (Bloom’s major poets) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7910-7391-2 1. Cummings, E. E. (Edward Estlin), 1894–1962—Criticism and interpretation. I. Bloom, Harold. II. Series. PS3505.U334Z59 2003 811’.52—dc21 2003000806 Chelsea House Publishers 1974 Sproul Road, Suite 400 Broomall, PA 19008-0914 http://www.chelseahouse.com Contributing Editor: Michael Baughan Cover design by Terry Mallon Layout by EJB Publishing Services CONTENTS User’s Guide 7 About the Editor 8 Editor’s Note 9 Introduction 10 Biography of E. E. Cummings 12 Critical Analysis of “All in green went my love riding” 16 Critical Views on “All in green went my love riding” 19 Barry Sanders on the Allusions to Diana 19 Will C. -

M OBAL IMTERPBETEB9S APPROACH to SELECTED

An oral interpreter's approach to selected poems by E. E. Cummings Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Holmes, Susanne Stanford, 1941- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 02:44:40 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318940 m OBAL IMTERPBETEB9 S APPROACH TO SELECTED POEMS BY E, E. CUMMINGS "by Susanne Stanford Holmes A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SPEECH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS t- In The Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 4 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable with out special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

A CATHOLIC CRITICISM of E. E. CUMMINGS a Study of Form

UNIVERSITY D-OTTAWA ~ ECOLE DES GRADUES A CATHOLIC CRITICISM OF E. E. CUMMINGS c ', i- •J. f » ifX. • A Study of Form, Technique and Content in one of the Controversial Poets of Our Time from the Traditional Christian Viewpoint* By Stephen Breen Thesis presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa through the Department of English as partial fulfill ment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 6. fWf Ottawa, Canada, 1958 AjU*A^&->w( \J \ 5 «• Q~\^- UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA - SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UMI Number: DC53307 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53307 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 UNIVERSITE D-OTTAWA ~ ECOLE DES GRADUES ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis topic was selected under the guidance of the Chairman of the English Department, Professor Emmett 0'Grady, and executed under the guidance of Dr. Paul Marcotte in its initial stages, with Dr. Brian Robinson directing its organization and conclusion. -

Marvelous Whirlings E.E. Cummings Eimi, Louis Aragon

MARVELOUS WHIRLINGS E.E. CUMMINGS EIMI, LOUIS ARAGON, EZRA POUND, & KRAZY KAT _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by JOSHUA D. HUBER Dr. Frances Dickey, Thesis Supervisor MAY 2015 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled MARVELOUS WHIRLINGS E.E. CUMMINGS EIMI, LOUIS ARAGON, EZRA POUND, & KRAZY KAT presented by Joshua D. Huber, a candidate for the degree of master of English, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Associate Professor Frances Dickey Professor Scott Cairns Professor Russ Zguta ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Grateful thanks to all those who aided me in the completion of this document, especially: my advisor, Dr. Frances Dickey (whose feedback, critiques, and suggestions were invaluable), committee members, Dr. Scott Cairns and Dr. Russell Zguta; my colleagues, both fellow graduate students and professors, at the University of Missouri; the staff of the University of Missouri for helping with the vast tides of paperwork this process requires; and, finally, my wife and family for encouragement and putting up with my sometimes anti-social and frequently bookish ways during this process. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………….. ii Chapter 1: Introduction ….…………………………………………………….. 1 Chapter 2: Dadaist Differentiation …………………………………………….. 9 2.1: Telemachus ...…………………………………………………….. 9 2.2: “The Red Front” ………………………………………………….. 15 Chapter 3: Pound and Cummings ……………………………………………... 26 3.1: The Cantos ………………………………………………………... 26 3.2: The Politics of Pound and Cummings ……………………………. 41 Chapter 4: Krazy Kat ………………………………………………………... 48 4.1: Krazy and Cummings’ Foreword …………………………………. -

Ee Cummings Poems: “O the Sun Comes Up- Up-Up in the Opening” (CP 773), “(Of Ever-Ever Land I Speak” (CP 466), and “I Thank You God for Most This Amazing” (CP 663)

EEC Society Blog. E E C S O C I E T Y B L O G for the leaping greenly spirits of trees AUT HO R: MICHAEL WEB S T ER CFP: E. E. Cummings Sessions at the American Literature Association’s 29th annual conference DECEMBER 16 , 20 17 / COMMENTS OFF The deadline for submitting abstracts for the ALA conference has been extended to January 27. (It cannot be extended further.) Here is the revised call for papers: E. E. Cummings Sessions at the American Literature Association’s 29th annual conference, San Francisco, CA, May 24-27, 2018 (deadline 1/27/2018) The E. E. Cummings Society will sponsor two sessions at the 2018 ALA. We invite proposals for papers on any aspect of Cummings’ life or work. Proposals that touch upon the following topics will be especially welcome: Cummings in 1917-1918 (detention at La Ferté Macé, Cummings at Camp Devens, The Enormous Room as a modernist memoir) Early experiments in modernism Readings of little-studied Cummings poems Re-readings of much-studied Cummings poems Cummings among the modernists and post-modernists Love and art vs. the unworld of modernity Submit 250-400 word abstracts to Michael Webster ([email protected]) by January 27, 2018. For further information, consult the web page of the American Literature Association conference. like & share: Call for Papers, Louisville Conference, February 22-24, 2018 JULY 28 , 20 17 / 0 COMMENTS CFP: E. E. Cummings Sessions at the Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture since 1900, University of Louisville, February 22-24, 2018 (deadline 9/8/2017) “my specialty is living said”: Modernist Rhythm, Visual Form, and Cummings’ Cultural Aesthetics The E. -

New^ Hampshire. Nnaamnn ——— O

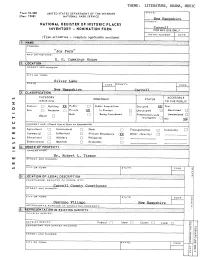

THEME: LITERATURE, DRAMA, MUSIC Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Dec. 1968) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE New Hampshire COUN TY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Carroll INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY EN TRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) 'joy Farm' AND/OR HISTORIC: E. E. Cummings House STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Silver Lake New^ Hampshire. CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District n Bui Iding Public a Public Acquisition: Occupied XiXJ Yes: Site n Structure a Private m In Process Unoccupied || Restricted Both Being Considered Preservation work Unrestricted Object n in progress || No: PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) Agricultural [ ] Government [ | Park Transportation | | Comments o Commercial Q Industrial Q Private Residence Other (Specify) n ——— Educational Q Military Q Religious Entertoinment Q] Museum | | Scientific OWNERS NAME: Mr. Robert L. Timmer STREET AND NUMBER: Cl TY OR TOWN: COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Carroll County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Ossippe Village New Hampshire APPROXIMATE ACREAGE OF NOMINATED PROPERTY: TITLE OF SURVEY: DATE OF SURVEY: Federal |~~1 State County Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: CONDITION (Check One) Excellent D Good Q Fair K Deteriorated Q R uins a Unexposed a (Check One) (Check One) INTEGRITY Altered ^3 Unaltered a Moved a Original Site fiQ The main house at "joy Farm" is a one-and-a-half story, white clapboarded structure with two interior chimnies. Its modified gable roof is flattened along the ridge to form a deck enclosed by a railing. -

E. E. Cummings Biography

E. E. Cummings Biography http://famouspoetsandpoems.com/poets/e__e__cummings/biography Edward Estlin Cummings was born October 14, 1894 in the town of Cambridge Massachusetts. His father, and most constant source of awe, Edward Cummings, was a professor of Sociology and Political Science at Harvard University. In 1900, Edward left Harvard to become the ordained minister of the South Congregational Church, in Boston. As a child, E.E. attended Cambridge public schools and lived during the summer with his family in their summer home in Silver Lake, New Hampshire. (Kennedy 8-9) E.E. loved his childhood in Cambridge so much that he was inspired to write disputably his most famous poem, "In Just-" (Lane pp. 26-27) Not so much in, "In Just-" but Cummings took his father's pastoral background and used it to preach in many of his other poems. In "you shall above all things be glad and young," Cummings preaches to the reader in verse telling them to love with naivete and innocence, rather than listen to the world and depend on their mind. Enlarge Picture Attending Harvard, Cummings studied Greek and other languages (p. 62). In college, Cummings was introduced to the writing and artistry of Ezra Pound, who was a large influence on E.E. and many other artists in his time (pp. 105-107). After graduation, Cummings volunteered for the Norton-Haries Ambulance Corps. En-route to France, Cummings met another recruit, William Slater Brown. The two became close friends, and as Brown was arrested for writing incriminating letters home, Cummings refused to separate from his friend and the two were sent to the La Ferte Mace concentration camp. -

E. E. Cummings: Modernist Painter and Poet Author(S): Milton A

E. E. Cummings: Modernist Painter and Poet Author(s): Milton A. Cohen Source: Smithsonian Studies in American Art, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Spring, 1990), pp. 54-74 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Smithsonian American Art Museum Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3108985 . Accessed: 05/04/2011 17:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Smithsonian American Art Museum are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Smithsonian Studies in American Art. -

Fliiiiiiiiii; STREET and NUMBER

THEME: LITERATURE, DRAMA, MUSIC Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Dec. 1968) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE New Hampshire NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY EN TRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) C OMMON: Joy Farm AND/OR HISTORIC: E. E. Cummings House fliiiiiiiiii; STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Silver Lake COUNTY: m^mmmsmmmmm CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District FJ Building Public a Public Acquisition: Occupied XiXJ Yes: Site Q Structure Private m In Process || Unoccupied [I Restricted Both Being Considered EH Preservation work Unrestricted Object n a in progress || No: PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) Agricultural [ | Government | | Park Transportation | | Comments o Commercial EH Industrial Q Private Residence Other (Specify) n ——— Educational [ | Military Q Religious [ | Entertainment | | Museum | | Scientific | | OWNERS NAME: Mr. Robert L. Timmer STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC: ___________Carroll County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Ossippe Village New Hampshire APPROXIMATE ACREAGE OF NOMINATED PROPERTY: TITLE OF SURVEY: DATE OF SURVEY: Federal [~~] State D County Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: fCftec/c One) CONDITION Excellent D Good (^D Fair g[ Deteriorated | | Ruins a Unexposed a (Check One) (Check One) INTEGRITY Altered ^] Unaltered a Mov ed n Original Site J£] DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The main house at HJoy Farm" is a one-and-a-half story, white clapboarded structure with two interior chimnies. Its modified gable roof is flattened along the ridge to form a deck enclosed by a railing. -

The Ambiguous Place of Popular Culture in EE Cummings'

“Damn everything but the circus!”: The Ambiguous Place of Popular Culture in E. E. Cummings’ Him Thomas Fahy At the age of six, Edward Estlin Cummings went to the circus for the first time. “Saw jaguars, hyena, bear, elephants, baby lion, and a father lion, baby monkeys climbing a tree,” he wrote excitedly in his diary that night (Kennedy 28). This experience left an indelible mark on Cummings, begin- ning a lifelong passion for the big top, sideshows, and wide range of popu- lar amusements. As biographer Richard S. Kennedy notes, the young Cum- mings relished family outings to the circus: “His father or his Uncle George took him to Forepaugh and Sells Brothers Circus (where he once rode an elephant), to Ringling Brothers, and on one glorious occasion to Barnum and Bailey where he saw sideshows for the first time—the freaks and sword-swallowers” (23). These moments inspired some of Cummings’ ear- liest poems and sketches, which featured circus acts and popular figures like Buffalo Bill Cody. As he worked to develop his own aesthetics and artistic philosophy in the teens and twenties, Cummings balanced his pas- sion for popular culture with a growing interest in Modernism. He read experimental prose and poetry, along with the Krazy Kat comic strip. He attended the Armory Show as well as vaudeville, minstrelsy, and side- shows. He listened to atonal music and ragtime. And he admired the Prov- incetown Players while frequenting burlesque and striptease acts. For Cum- mings, these amusements had a vitality that was often missing from high art—a vitality he wanted to capture in his own work.