Harold Bloom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News, Notes, & Correspondence

News, Notes, & Correspondence The Theatre of E. E. Cummings Published In the News, Notes & Correspondence section of Spring 18, we re- ported that a new edition of The Theatre of E. E. Cummings was in the works, and—behold!—the book appeared on schedule at the beginning of 2013. This book, which contains the plays Him, Anthropos, and Santa Claus, along with the ballet Tom, provides readers with a handy edition of Cummings’ theatre works. The book also has an afterword by Norman Friedman, “E. E. Cummings and the Theatre,” which we printed in Spring 18 (94-108). The Thickness of the Coin In February, 2012 we received a card from Zelda and Norman Fried- man. They wrote: We are okay and want to tell you that the older we get the more skillful and wise E. E. Cummings becomes. Zelda has been trying to locate the line “love makes the little thickness of the coin” and came upon it accidentally in “hate blows a bubble of despair into” across the page in Complete Poems from “love is more thicker than forget”—the poem where she thought it might be. The Cummings-Clarke Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society *In October 2012, Peter Steinberg of the Massachusetts Historical Society wrote to inform us that some of the Cummings-Clarke family papers con- taining “some materials by E. E. Cummings” had “recently been processed and made available for research.” Peter sent us the following “link to the finding aid / collection guide in hopes that you or your society members might be interested in learning about [the papers and] visiting the MHS”: http://www.masshist.org/findingaids/doc.cfm?fa=fa0367. -

Ee Cummings Poems: “O the Sun Comes Up- Up-Up in the Opening” (CP 773), “(Of Ever-Ever Land I Speak” (CP 466), and “I Thank You God for Most This Amazing” (CP 663)

EEC Society Blog. E E C S O C I E T Y B L O G for the leaping greenly spirits of trees AUT HO R: MICHAEL WEB S T ER CFP: E. E. Cummings Sessions at the American Literature Association’s 29th annual conference DECEMBER 16 , 20 17 / COMMENTS OFF The deadline for submitting abstracts for the ALA conference has been extended to January 27. (It cannot be extended further.) Here is the revised call for papers: E. E. Cummings Sessions at the American Literature Association’s 29th annual conference, San Francisco, CA, May 24-27, 2018 (deadline 1/27/2018) The E. E. Cummings Society will sponsor two sessions at the 2018 ALA. We invite proposals for papers on any aspect of Cummings’ life or work. Proposals that touch upon the following topics will be especially welcome: Cummings in 1917-1918 (detention at La Ferté Macé, Cummings at Camp Devens, The Enormous Room as a modernist memoir) Early experiments in modernism Readings of little-studied Cummings poems Re-readings of much-studied Cummings poems Cummings among the modernists and post-modernists Love and art vs. the unworld of modernity Submit 250-400 word abstracts to Michael Webster ([email protected]) by January 27, 2018. For further information, consult the web page of the American Literature Association conference. like & share: Call for Papers, Louisville Conference, February 22-24, 2018 JULY 28 , 20 17 / 0 COMMENTS CFP: E. E. Cummings Sessions at the Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture since 1900, University of Louisville, February 22-24, 2018 (deadline 9/8/2017) “my specialty is living said”: Modernist Rhythm, Visual Form, and Cummings’ Cultural Aesthetics The E. -

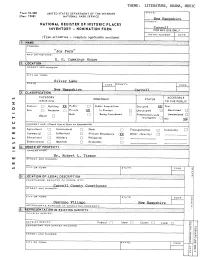

New^ Hampshire. Nnaamnn ——— O

THEME: LITERATURE, DRAMA, MUSIC Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Dec. 1968) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE New Hampshire COUN TY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Carroll INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY EN TRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) 'joy Farm' AND/OR HISTORIC: E. E. Cummings House STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Silver Lake New^ Hampshire. CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District n Bui Iding Public a Public Acquisition: Occupied XiXJ Yes: Site n Structure a Private m In Process Unoccupied || Restricted Both Being Considered Preservation work Unrestricted Object n in progress || No: PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) Agricultural [ ] Government [ | Park Transportation | | Comments o Commercial Q Industrial Q Private Residence Other (Specify) n ——— Educational Q Military Q Religious Entertoinment Q] Museum | | Scientific OWNERS NAME: Mr. Robert L. Timmer STREET AND NUMBER: Cl TY OR TOWN: COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Carroll County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Ossippe Village New Hampshire APPROXIMATE ACREAGE OF NOMINATED PROPERTY: TITLE OF SURVEY: DATE OF SURVEY: Federal |~~1 State County Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: CONDITION (Check One) Excellent D Good Q Fair K Deteriorated Q R uins a Unexposed a (Check One) (Check One) INTEGRITY Altered ^3 Unaltered a Moved a Original Site fiQ The main house at "joy Farm" is a one-and-a-half story, white clapboarded structure with two interior chimnies. Its modified gable roof is flattened along the ridge to form a deck enclosed by a railing. -

E. E. Cummings Biography

E. E. Cummings Biography http://famouspoetsandpoems.com/poets/e__e__cummings/biography Edward Estlin Cummings was born October 14, 1894 in the town of Cambridge Massachusetts. His father, and most constant source of awe, Edward Cummings, was a professor of Sociology and Political Science at Harvard University. In 1900, Edward left Harvard to become the ordained minister of the South Congregational Church, in Boston. As a child, E.E. attended Cambridge public schools and lived during the summer with his family in their summer home in Silver Lake, New Hampshire. (Kennedy 8-9) E.E. loved his childhood in Cambridge so much that he was inspired to write disputably his most famous poem, "In Just-" (Lane pp. 26-27) Not so much in, "In Just-" but Cummings took his father's pastoral background and used it to preach in many of his other poems. In "you shall above all things be glad and young," Cummings preaches to the reader in verse telling them to love with naivete and innocence, rather than listen to the world and depend on their mind. Enlarge Picture Attending Harvard, Cummings studied Greek and other languages (p. 62). In college, Cummings was introduced to the writing and artistry of Ezra Pound, who was a large influence on E.E. and many other artists in his time (pp. 105-107). After graduation, Cummings volunteered for the Norton-Haries Ambulance Corps. En-route to France, Cummings met another recruit, William Slater Brown. The two became close friends, and as Brown was arrested for writing incriminating letters home, Cummings refused to separate from his friend and the two were sent to the La Ferte Mace concentration camp. -

E. E. Cummings: Modernist Painter and Poet Author(S): Milton A

E. E. Cummings: Modernist Painter and Poet Author(s): Milton A. Cohen Source: Smithsonian Studies in American Art, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Spring, 1990), pp. 54-74 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Smithsonian American Art Museum Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3108985 . Accessed: 05/04/2011 17:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Smithsonian American Art Museum are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Smithsonian Studies in American Art. -

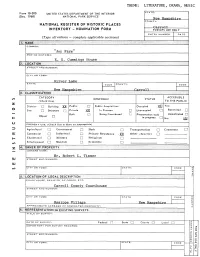

Fliiiiiiiiii; STREET and NUMBER

THEME: LITERATURE, DRAMA, MUSIC Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Dec. 1968) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE New Hampshire NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY EN TRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) C OMMON: Joy Farm AND/OR HISTORIC: E. E. Cummings House fliiiiiiiiii; STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Silver Lake COUNTY: m^mmmsmmmmm CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District FJ Building Public a Public Acquisition: Occupied XiXJ Yes: Site Q Structure Private m In Process || Unoccupied [I Restricted Both Being Considered EH Preservation work Unrestricted Object n a in progress || No: PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) Agricultural [ | Government | | Park Transportation | | Comments o Commercial EH Industrial Q Private Residence Other (Specify) n ——— Educational [ | Military Q Religious [ | Entertainment | | Museum | | Scientific | | OWNERS NAME: Mr. Robert L. Timmer STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC: ___________Carroll County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Ossippe Village New Hampshire APPROXIMATE ACREAGE OF NOMINATED PROPERTY: TITLE OF SURVEY: DATE OF SURVEY: Federal [~~] State D County Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: fCftec/c One) CONDITION Excellent D Good (^D Fair g[ Deteriorated | | Ruins a Unexposed a (Check One) (Check One) INTEGRITY Altered ^] Unaltered a Mov ed n Original Site J£] DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The main house at HJoy Farm" is a one-and-a-half story, white clapboarded structure with two interior chimnies. Its modified gable roof is flattened along the ridge to form a deck enclosed by a railing. -

News, Notes, & Correspondence

News, Notes, & Correspondence Act III of Him to Appear in Anthology *Cummings’ play Him has long been out of print, but we are pleased to announce that at least Act III of the play will soon be available. On June 12, 2009 Sarah Bay-Cheng wrote to inform us that she was “about to pub- lish an anthology of modernist poetic drama (including the third act of Cummings’ Him).” The anthology, edited along with Barbara Cole, called Poets at Play: An Anthology of Modernist Drama, was published by Sus- quehanna University Press (Associated University Presses) in April of 2010. The cover features Cummings’ drawing of burlesque and vaudeville comedian Jack Shargel. The publisher’s blurb follows. Poets at Play: An Anthology of Modernist Drama is the first book in more than thirty years to consider the dramatic and theatrical legacy of American modernist poets, making these plays accessible to students and scholars in one volume. This critical anthology presents selected plays by American poets writing between 1916 and 1956—Wallace Stevens, Edna St. Vincent Millay, H. D., E. E. Cummings, Marita Bon- ner, William Carlos Williams, Gertrude Stein, and Ezra Pound. Begin- ning with Stevens’s Three Travelers Watch a Sunrise (1916) as a dy- namic introduction to the modernist transformation of poetry into per- formance, the collection also includes Millay’s biting anti-war satire, Aria da Capo (1920) and H. D.’s Hippolytus Temporizes (1927), loosely adapted from the Euripides play. Despite being out of print for more than twenty-five years, Cummings’s Him (1927), combines ab- surd wordplay and nonlinear dramatic structure, in what may be called American dada, to comment on the theater, popular culture, and sexual politics against the darkening background of pre-World War II geopoli- tics. -

Edward Estlin Cummings

Classic Poetry Series Edward Estlin Cummings - 45 poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: PoemHunter.Com - The World's Poetry Archive Edward Estlin Cummings (14 October 1894 - 3 September 1962) Edward Estlin Cummings, popularly known as E. E. Cummings, with the abbreviated form of his name often written by others in all lowercase letters as e. e. cummings, was an American poet, painter, essayist, author, and playwright. His body of work encompasses approximately 2,900 poems, an autobiographical novel, four plays and several essays, as well as numerous drawings and paintings. He is remembered as a preeminent voice of 20th century poetry, as well as one of the most popular. Birth and early years Cummings was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on October 14, 1894 to Edward and Rebecca Haswell Clarke Cummings. He was named after his father but his family called him by his middle name. Estlin's father was a professor of sociology and political science at Harvard University and later a Unitarian minister. Cummings described his father as a hero and a person who could accomplish anything that he wanted to. He was well skilled and was always working or repairing things. He and his son were close, and Edward was one of Cummings' most ardent supporters. His mother, Rebecca, never partook in stereotypically "womanly" things, though she loved poetry and reading to her children. Raised in a well-educated family, Cummings was a very smart boy and his mother encouraged Estlin to write more and more poetry every day. His first poem came when he was only three: "Oh little birdie oh oh oh, With your toe toe toe." His sister, Elizabeth, was born when he was six years old. -

Muoz-Elefantesyrascacielos.Pdf

1 9 3 9 - 2 0 1 9 ELEFANTES & RASCACIELOS Editorial de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Centro Universitario, Ciudad de Mendoza (5500) Tel: (261) 4135000Interno Editorial: 2240 - [email protected] Muñoz, María Victoria Elefantes&rascacielos : tradición e innovación en la poesía de E.E.Cummings / María Victoria Muñoz. - 1a edición para el profesor - Mendoza : Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, 2019. 215 p. ; 21 x 15 cm. ISBN 978-950-774-357-3 1. Estudios Literarios. I. Título. CDD 807 Imagen de tapa: acuarela de Andrea Zucol "Ganesha" Diseño gráfico y maquetación: Clara Luz Muñiz Versión impresa: Talleres Gráficos de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, UNCUYO, Argentina - Printed in Argentina Se permite la reproducción de los artículos siempre y cuando se cite la fuente. Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Atribución-NoComercial- CompartirIgual 2.5 Argentina (CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 AR. Usted es libre de: copiar y redistribuir el material en cualquier medio o formato; adaptar, transformar y construir a partir del material citando la fuente. Bajo los siguientes términos: Atribución —debe dar crédito de manera adecuada, brindar un enlace a la licencia, e indicar si se han realizado cambios. Puede hacerlo en cualquier forma razonable, pero no de forma tal que sugiera que usted o su uso tienen el apoyo de la licenciante. NoComercial —no puede hacer uso del material con propósitos comerciales. CompartirIgual — Si remezcla, transforma o crea a partir del material, debe distribuir su contribución bajo la lamisma licencia del original. -

" Mum STATE UNIVERSITY * F Wllliam ELUOT THOMPSON 1.976

MEANING AND TECHNIQUE: _UNlTY IN THE LATER POETRY~ ; ' 0F e.e.cumm"ing‘s ' _’ v———w+ Dissertation forthé Degree of Ph. 'D. v " mum STATE UNIVERSITY * f WlLLIAM ELUOT THOMPSON 1.976 . - f llllllllllllllllll u Michigan 59!! University This is to certify that the thesis entitled MEANING AND TECHNIQUE: UNITY IN THE LATER POETRY OF e. e. cummings presented by WILLIAM ELLIOT THOMPSON has been accepted towards fulfillment of the requirements for Ph.D. degree in EngliSh if” C kwfi Major professor Date/ OJ, / 28, / 7740 0-7639 ’ Eflfifnl’ll'u'i‘“ tummy. «£23 LTVAm’ ABSTRACT MEANING AND TECHNIQUE: UNITY IN THE LATER POETRY OF e. e. cummings BY William Elliot Thompson The criticism most persistently made during the half-century of e. e. cummings' writing career was that he was limited by "permanent adolescence." Every admirer of cummings' unique style has had to counter this charge; accordingly, cummings' life-view has been compared to the philosophies of the Romantic poets, to Martin Buber‘s "I-thou" concept and to the christian (with a lower case "0") love ethic. This dissertation employs a humanistic psychological analysis of cummings' life-view to affirm the positive value of his vision. In the first four chapters I inductively derive the major elements of his life-view from his poems, fiction and prose, demonstrating a reading process which any careful reader can replicate, showing by example the processes a reader might use to discover the ethical system expressed in the poems. Comparison of the major elements of cummings' life-view with the principles of William Elliot Thompson Abraham Maslow's "Psychology of Being" shows that, accord- ing to Maslovian standards of health, cummings' persona presents attitudes which are mature, humanistic and psy- chologically healthy.