Demystifying the Root Causes of Violent Conflicts in South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Institute of Peace Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Sudan Experience Project

United States Institute of Peace Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Sudan Experience Project Interview # 81 – Executive Summary Interviewed by: Barbara Nielsen Initial interview date: May 26, 2007 Copyright 2007 USIP & ADST The interviewee is an architect of Sudanese origin. In addition to his architectural work, he works with a variety of organizations to promote awareness regarding the conflict in Darfur and assist in the realization of peace throughout Sudan. The Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) has provided for a stable peace between the Sudanese government in Khartoum and the Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/SPLM). U.S. involvement was critical in the development of the CPA. The United States exerted political pressure on the Sudanese government to engage in negotiations with the SPLA/SPLM. Still, the Khartoum government remains reluctant to implement certain provisions of the CPA. After 22 years of war, the SPLA/SPLM is rapidly transforming from a warring faction to a legitimate political party. The Sudanese government has used a technique of “divide and conquer” as a means to weaken the political influence of southern Sudan. It has employed corrupt mechanisms in encouraging SPLA/SPLM leaders, such as Riek- Machar and Lam Akol, to split off from the main faction. But other entities have largely succeeded in reuniting these groups. The United States, as well as certain Scandinavian and Christian groups, have played a key role in this process. Salva Kiir, Vice President of Sudan and President of the autonomous government of Southern Sudan, has also successfully promoted the unity of SPLM. While certain critics claim the CPA is too complex for successful implementation, the comprehensive and detailed nature of the agreement has assured widespread confidence in continued peace. -

The Crisis in South Sudan

Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs September 22, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43344 Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Summary South Sudan, which separated from Sudan in 2011 after almost 40 years of civil war, was drawn into a devastating new conflict in late 2013, when a political dispute that overlapped with preexisting ethnic and political fault lines turned violent. Civilians have been routinely targeted in the conflict, often along ethnic lines, and the warring parties have been accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The war and resulting humanitarian crisis have displaced more than 2.7 million people, including roughly 200,000 who are sheltering at U.N. peacekeeping bases in the country. Over 1 million South Sudanese have fled as refugees to neighboring countries. No reliable death count exists. U.N. agencies report that the humanitarian situation, already dire with over 40% of the population facing life-threatening hunger, is worsening, as continued conflict spurs a sharp increase in food prices. Famine may be on the horizon. Aid workers, among them hundreds of U.S. citizens, are increasingly under threat—South Sudan overtook Afghanistan as the country with the highest reported number of major attacks on humanitarians in 2015. At least 62 aid workers have been killed during the conflict, and U.N. experts warn that threats are increasing in scope and brutality. In August 2015, the international community welcomed a peace agreement signed by the warring parties, but it did not end the conflict. -

South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’S Newest Country

The Republic of South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’s Newest Country Ted Dagne Specialist in African Affairs July 1, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41900 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Republic of South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’s Newest Country Summary In January 2011, South Sudan held a referendum to decide between unity or independence from the central government of Sudan as called for by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement that ended the country’s decades-long civil war in 2005. According to the South Sudan Referendum Commission (SSRC), 98.8% of the votes cast were in favor of separation. In February 2011, Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir officially accepted the referendum result, as did the United Nations, the African Union, the European Union, the United States, and other countries. On July 9, 2011, South Sudan is to officially declare its independence. The Obama Administration welcomed the outcome of the referendum and pledged to recognize South Sudan as an independent country in July 2011. The Administration is expected to send a high-level presidential delegation to South Sudan’s independence celebration on July 9, 2011. A new ambassador is also expected to be named to South Sudan. South Sudan faces a number of challenges in the coming years. Relations between Juba, in South Sudan, and Khartoum are poor, and there are a number of unresolved issues between them. The crisis in the disputed area of Abyei remains a contentious issue, despite a temporary agreement reached in mid-June 2011. -

Addis PEACE a 411St ME HEADS O BANJUL, 30 DECEM AFRICAN

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, P.O. Box: 3243 Tel.: (251‐11) 5513 822 Fax: (251‐11) 5519 321 Email: situationroom@africa‐union.org PEACE AND SECURITY COUNCIL 411st MEETING AT THE LEVEL OF HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT BANJUL, THE GAMBIA 30 DECEMBER 2013 PSC/AHG/3(CDXI) REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON OFF THE COMMISSION ON THE SITUATION IN SOUTH SUDAN PSC/AHG/3(CDXI) Page 1 REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON OF THE COMMISSION ON THE SITUATION IN SOUTH SUDAN I. INTRODUCTION 1. The present report is submitted in the context of the meeting of Council to be held in Banjul, The Gambia, on 30 December 2013, to deliberate on the unfolding situation in South Sudan. The conflict in South Sudan erupted on 15 December, in the context of a political challenge to the President of the Republic of South Sudan, from leading members of the ruling party, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM). This rapidly mutated into violent confrontation and rebellion. The conflict imperils the lives and wellbeing of South Sudanese, jeopardizes the future of the young nation, and is a threat to regional peace and security. 2. The report provides a background to the current crisis, a chronology of the events of the last six months and an overview of the regional, continental and international response. The report concludes with observations on the way forward. II. BACKGROUND 3. The current conflict represents the accumulation of unresolved political disputes within the leadership of the SPLM. The leaders had disagreements on fundamental aspects of the party and country’s leadership, governance and direction. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

Human Security in Sudan: the Report of a Canadian Assessment Mission

Human Security in Sudan: The Report of a Canadian Assessment Mission Prepared for the Minister of Foreign Affairs Ottawa, January 2000 Disclaimer: This report was prepared by Mr. John Harker for the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. The views and opinions contained in this report are not necessarily those of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. 1 Human Security in Sudan: Executive Summary 1 Introduction On October 26, 1999, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Lloyd Axworthy and the Minister for International Co-operation, Maria Minna, announced several Canadian initiatives to bolster international efforts backing a negotiated settlement to the 43-year civil war in Sudan, including the announcement of an assessment mission to Sudan to examine allegations about human rights abuses, including the practice of slavery. There are few other parts of the world where human security is so lacking, and where the need for peace and security - precursors to sustainable development - is so pronounced. Canada's commitment to human security, particularly the protection of civilians in armed conflict, provides a clear basis for its involvement in Sudan and its support for the peace process. Charm Offensive, or Signs of Progress? Following the visit to Khartoum of an EU Mission, a political dialogue was launched by the European Union on November 11 1999. The EU was of the view that there has been sufficient progress in Sudan to warrant a renewed dialogue. In this view, there has been a positive change, and it is necessary to encourage the Sudanese, and push them further where there is need. -

From Independence to Civil War Atrocity Prevention and US Policy Toward South Sudan

From Independence to Civil War Atrocity Prevention and US Policy toward South Sudan Jon Temin July 2018 CONTENTS Foreword ............................................................................................................................. i Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 4 Project Background .......................................................................................................... 7 The South Sudan Context ................................................................................................ 9 Post-Benghazi, Post-Rwanda ...................................................................................... 9 Long US History and Friendship .............................................................................. 10 Hostility Toward Sudan and Moral Equivalence ...................................................... 11 Divergent Perceptions of Influence and Leverage .................................................. 11 Pivotal Periods ................................................................................................................ 13 1. Spring/Summer 2013: Opportunity for Prevention? ........................................... 13 2. Late 2013/Early 2014: The Uganda Question ....................................................... 17 3. Early 2014: Arms Embargo—A -

CRP on the Report of the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan in English2

United Nations A/HRC/37/CRP.2 General Assembly Distr.: Restricted 23 February 2018 Original: English Human Rights Council Thirty-seventh session Agenda item 4 Human Rights Situations that require the attention of the Council Report of the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan* * The information contained in this document should be read in conjunction with the report of the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan (A/HRC/37/71). GE. CRP on the Report of the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan in English2 Contents Page I. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 II. Mandate/Methodology ........................................................................................................................... 3 A. Mandate ......................................................................................................................................... 3 B. Methodology .................................................................................................................................... 4 C. The Commission’s work .................................................................................................................. 6 III. Background ......................................................................................................................................... 7 A. Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (2015)..................... 7 B. Breakdown -

Interna Tional Edition

Number 2 2014 ISSN 2196-3940 INTERNATIONAL South Sudan’s Newest War: When Two Old Men Divide a Nation Carlo Koos and Thea Gutschke A political power struggle between South Sudanese president Salva Kiir and former vice president Riek Machar resulted in violent clashes between ethnic army factions in December 2013. Since then fighting has spread across South Sudan and claimed the lives of around 10,000 people. Analysis South Sudan has experienced several insurgencies since gaining independence in 2011. Nevertheless, the current war has the potential to be more destructive to the country than previous ones because both parties – President Salva Kiir, an ethnic Dinka, and his opponent, former vice president Riek Machar, an ethnic Nuer – are instrumentalizing ethnic identities and pulling their communities into their personal feud. A number of latent issues have contributed to the current crisis. These include South Sudan’s dysfunctional political system and inadequate political leadership, the historical distrust between the Dinka and the Nuer, and the country’s unhealthy EDITION dependence on oil rents. The civilian population is carrying the cost of the conflict. More than 10,000 people have been killed and more than one million displaced since the outbreak of the latest violence. Livelihoods have been destroyed and more than 3.7 million people, approximately a third of the population, are estimated to be at risk of food insecurity. The short- and long-term economic consequences for South Sudan are harsh. Oil production has dropped by 40 percent, severely affecting the state’s budget. Trade has suffered. In the long run, political instability will jeopardize foreign direct investment in South Sudan. -

Hostilities Between Sudan and South Sudan a Timeline of Recent Events

Hostilities between Sudan and South Sudan A Timeline of Recent Events April 2012 February 11, 2012: Sudan and South Sudan sign a “non-aggression” pact during talks in Addis Ababa agreeing to “respect for each other’s sovereignty and territorial integrity” and to “refrain from launching any attack, including bombardment.” 1 March 13, 2012: Sudan and South Sudan initial two agreements in Addis Ababa that, if signed, would grant South Sudanese and Sudanese citizens certain freedoms in the other state, and commit the two states to a timeline to demarcate the agreed-upon areas of the North-South border.2 The round of talks concludes in a new “spirit of coopera- tion,” and with the announcement that the agreements would be signed in a bilateral summit attended by the two heads of states in Juba.3 March 23, 2012: Pagan Amum, South Sudan’s chief negotiator in talks with Sudan over outstanding post-independence issues, travels to Khartoum and personally delivers a letter of invitation to the President al-Bashir to join in a summit with Kiir in South Sudan. Bashir accepts the invitation.4 March 26, 2012: Clashes break out between Sudan’s and South Sudan’s armies in the disputed oil-rich area of Heglig.5 Both sides trade accusations about who instigated the violence. Southern officials accuse Khartoum of bombing southern troops in the disputed border area of Jau and of launching a ground attack on South Sudan bases south of Heglig oil field. Khartoum denies bombing Jau and accuses South Sudan of attacking Heglig with the support of Darfur rebels. -

HATE SPEECH MONITORING and CONFLICT ANALYSIS in SOUTH SUDAN Report #6: October 10 – October 23, 2017

October 25, 2017 HATE SPEECH MONITORING AND CONFLICT ANALYSIS IN SOUTH SUDAN Report #6: October 10 – October 23, 2017 This report is part of a broader initiative by PeaceTech Lab to analyze online hate speech in South Sudan in order to help mitigate the threat of hateful language in fueling violence on-the-ground. Hate speech can be defined as language that can incite others to discriminate or act against individuals or groups based on their ethnic, religious, racial, gender or national identity. The Lab also acknowledges the role of “dangerous speech,” which is a heightened form of hate speech that can catalyze mass violence. Summary of Recent Events uring this reporting period, military clashes continued throughout the Greater Equatoria and Upper Nile regions, both between rebel and government D forces, and among various rebel groups. On October 17, a contingent of National Salvation Front (NAS) fighters under General Thomas Cirillo overran SPLA-IO training bases around Kajo-Keji in Central Equatoria. The assaults occurred shortly after the SPLA-IO captured strategic barracks from government forces. The NAS itself claims that it was attacked by SPLA-IO forces, precipitating a counter-attack. It is unclear whether the NAS attack was coordinated with pro-government forces or conducted separately. The NAS rebel movement, composed mostly of Equatorians, is opposed to perceived Dinka dominance in government institutions, but is also not on good terms with the SPLA-IO. Meanwhile in Jonglei state, the divisions between Dinka Bor South and Dinka Twic East culminated in the passage of a bill in state parliament that seeks to split the state into two parts: Bor (to be based in Bor town) and Jonglei (to be headquartered in Panyagor). -

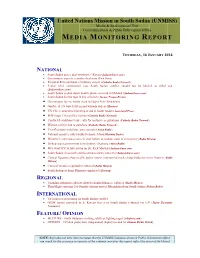

Med Ia M Onit Torin Ng Re Epor T

United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) Media & Spokesperson Unit Communications & Public Information Office MEDIA MONITORING REPORT THURSDAY, 16 JANUARY 2014 NATIONAL • South Sudan peace deal imminent – Kenya (Sudantribune.com) • Government expects ceasefire deal soon (VoA News) • President Kiir confident of miltiary victory (Catholic Radio Network) • Senior rebel commander says South Sudan conflict should not be labeled as tribal war (Sudantribune.com) • South Sudan to shut down mobile phone network in Malakal (Sudantribune.com) • South Sudan battles rage in key oil town (Agence France-Presse) • Government forces, rebels clash in Upper Nile (VoA News) • Gunfire at UN base kills on and wounds dozens (Reuters) • UN Chief condemns hijacking of aid in South Sudan (Associated Press) • MSF treats 116 conflict victims (Catholic Radio Network) • Conflict Resolution Centre calls for inclusive negotiations (Catholic Radio Network) • Women call for end to gunshots (Catholic Radio Network) • Vice-President mobilises army recruits (Anisa Radio) • National minister calls youths to donate blood (Bakhita Radio) • Minority leader raises concern over failuure to endorse state of emergency (Radio Miraya) • Bishop urges government to end ethnic cleansing (Anisa Radio) • MPs want ICC to take action on Dr. Riek Machar (Sudantribune.com) • South Sudan closes universities amid security concerns (Sudantribune.com) • Central Equatoria State traffic police orders commercial trucks, boda bodas to renew licenses (Radio MIraya) • Cases of measles reported in Awerial (Radio Miraya) • South Sudanese from Diaspora employed (Gurtong) REGIONAL • Ugandan authorities allocate plots to South Sudanese refugees (Radio Miraya) • Third flight carrying 200 Somali citizens arrives Mogadishu from South Sudan (Daalsan Radio) INTERNATIONAL • US issues stern warning on South Sudan conflict • GSDF ammo provided to S.