1852 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Billing Outline First Son John Who Married Margery Blewet and Settled at St Tudy in the 1540S

THE HERALD’S VISITATION OF 1620 FOCUSED SOLELY ON THE LINE OF JOHN BILLING / TRELAWDER’S 6 miles BILLING OUTLINE FIRST SON JOHN WHO MARRIED MARGERY BLEWET AND SETTLED AT ST TUDY IN THE 1540S. Summary of what is a rather large chart: BILLING update, December 2018. The rest of the family successfully finished their 1000 National Archives document R/5832 has a supposed date of 24 April 1512; but is This outline sets out the BILLING alias TRELAWDER family connections in Cornwall THIS LINE IS SHOWN HERE IN PURPLE ON THE LEFT HAND SIDE AS SET OUT IN 1874 BY THE HARLEIAN piece jigsaw puzzle; but sadly we have not been so successful in joining together the many over two hundred years. It is unusual to see an alias - our modern equivalent being the SOCIETY AND USED BY SIR JOHN MACLEAN IN HIS RESEARCH. endorsed with a note by C.G.. Henderson “This deed was forged about 17 Eliz. [1577] hundreds of pieces that make up the BILLING alias TRELAWDER story. by Nicholas Beauchamp of Chiton (denounced by the Devon Jury)” hyphenated name - being sustained over so long a time. OTHER BRANCHES OF THE FAMILY STAYED IN ST MINVER AND IN THE ST BREOCK / EGLOSHAYLE AREA. ST TUDY LINE LEFT In many cases, no connections are attempted. At other times links have been suggested. THESE WERE NOT CHRONICLED, BUT WE MAY ASSUME THAT RICHARD, AT ST MINVER IN 1523, AND As mentioned earlier, the 1874 book on the Cornwall Visitations by the Harleian Society, The spelling of TRELAWDER does vary, sometimes TRELODER or TRELOTHER etc. -

Parish Boundaries

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

View in Website Mode

25 bus time schedule & line map 25 Fowey - St Austell - Newquay View In Website Mode The 25 bus line (Fowey - St Austell - Newquay) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Fowey: 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM (2) Newquay: 5:55 AM - 3:55 PM (3) St Austell: 5:58 PM (4) St Austell: 5:55 PM (5) St Stephen: 4:55 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 25 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 25 bus arriving. Direction: Fowey 25 bus Time Schedule 94 stops Fowey Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM Bus Station, Newquay 16 Bank Street, Newquay Tuesday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM East St. Post O∆ce, Newquay Wednesday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM 40 East Street, Newquay Thursday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM Great Western Hotel, Newquay Friday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM 36&36A Cliff Road, Newquay Saturday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM Tolcarne Beach, Newquay 12A - 14 Narrowcliff, Newquay Barrowƒeld Hotel, Newquay 25 bus Info Hilgrove Road, Trenance Direction: Fowey Stops: 94 Newquay Zoo, Trenance Trip Duration: 112 min Line Summary: Bus Station, Newquay, East St. Post The Bishops School, Treninnick O∆ce, Newquay, Great Western Hotel, Newquay, Tolcarne Beach, Newquay, Barrowƒeld Hotel, Kew Close, Treloggan Newquay, Hilgrove Road, Trenance, Newquay Zoo, Kew Close, Newquay Trenance, The Bishops School, Treninnick, Kew Close, Treloggan, Dale Road, Treloggan, Polwhele Road, Dale Road, Treloggan Treloggan, Near Morrisons Store, Treloggan, Carn Brae House, Lane, Hendra Terrace, Hendra Holiday Polwhele Road, Treloggan Park, Holiday -

20 Egloshayle Road, Wadebridge, Cornwall, Pl27 6Ad

PROPOSED EXTENSION TO : 20 EGLOSHAYLE ROAD, WADEBRIDGE, CORNWALL, PL27 6AD (REV. A) 2003: 20 EGLOSHAYLE ROAD Issue Status Date Revision Author Details 19.02.2021 - AW Issued for Planning RIBA STAGE 3: HERITAGE STATEMENT 22.02.2021 A AW Issued for Planning - Rev.A PREPARED ON BEHALF OF: MR AND MRS PATTERSON L IL H K A er I n n VEN o ver N 7 w 5 a GO A 6 9 o 5 t ar Bank va 1 Gonvena Str T y 6 l 1 r o S e e 6 Well Manor T n r ath T r 7 x e i OSE D u g se 24.6m 7 L C House ea N l C 1 in o am L 2a l et h ER OA o a EER 1 Trevarner L 0 R M n 1 2 h SH 1 IL b M 3 L I Tank L er C F H K The Beeches e o ittl 7 S r er o e a wo B e D R i n r a m EW r yn n b H R A 1 k e T r o T P H Depot A I a V 7 i C d M S B g o ST E f h ttag ie W ES l D B 6 Purpose of the Statement: e r a e 3a a H R te Issues 2 in i St D 3 r T g b d R M El e h 1 o EVI i f 1 4 1 l c Sub Sta a o an h l R a 7 4b F L en e l 5 4c L d 's IN Alpen s sb G T u r R Rose e rg O d Trevarner Heverswood an 4a 1 A 2 2 D n 1 D en VI ROA Cottages 3 K 1 R C S PA 4b Bureau Pencarn 16.8m T 1 ES Allen Trevarin 1 B 4 1 d PI House OR n G U FIGURE 4 Car Park House Coombe Florey GY I .6m A 60.3m 11 PA LA s The k 4 BS N Mud r Lodge 1 E Wks o R K f (T Pumping Slipway W OSE 6 r 5 L 8 ack) y ) 1 C 1 a KLIN F Station w (PH An Tyak FRAN W lip g 5 rin a Sp n 1 6 S 0 CHARACTER AREAS D n n 2 1 R Gardens e I re Trenant r g p El Su b Sta o a i 4 ar d a C se Cott r h 1 W ea Farm i o a S M n M G K tt 2 Little 2 El 3 i L 1 2 n B 4 21 K g W R Su e R Trenant fi A c PA 5 0 IA 1 3 D 1 44 sh F b la OR 1 .9 OR P CT 1 er St 1 -

Copyrighted Material

176 Exchange (Penzance), Rail Ale Trail, 114 43, 49 Seven Stones pub (St Index Falmouth Art Gallery, Martin’s), 168 Index 101–102 Skinner’s Brewery A Foundry Gallery (Truro), 138 Abbey Gardens (Tresco), 167 (St Ives), 48 Barton Farm Museum Accommodations, 7, 167 Gallery Tresco (New (Lostwithiel), 149 in Bodmin, 95 Gimsby), 167 Beaches, 66–71, 159, 160, on Bryher, 168 Goldfish (Penzance), 49 164, 166, 167 in Bude, 98–99 Great Atlantic Gallery Beacon Farm, 81 in Falmouth, 102, 103 (St Just), 45 Beady Pool (St Agnes), 168 in Fowey, 106, 107 Hayle Gallery, 48 Bedruthan Steps, 15, 122 helpful websites, 25 Leach Pottery, 47, 49 Betjeman, Sir John, 77, 109, in Launceston, 110–111 Little Picture Gallery 118, 147 in Looe, 115 (Mousehole), 43 Bicycling, 74–75 in Lostwithiel, 119 Market House Gallery Camel Trail, 3, 15, 74, in Newquay, 122–123 (Marazion), 48 84–85, 93, 94, 126 in Padstow, 126 Newlyn Art Gallery, Cardinham Woods in Penzance, 130–131 43, 49 (Bodmin), 94 in St Ives, 135–136 Out of the Blue (Maraz- Clay Trails, 75 self-catering, 25 ion), 48 Coast-to-Coast Trail, in Truro, 139–140 Over the Moon Gallery 86–87, 138 Active-8 (Liskeard), 90 (St Just), 45 Cornish Way, 75 Airports, 165, 173 Pendeen Pottery & Gal- Mineral Tramways Amusement parks, 36–37 lery (Pendeen), 46 Coast-to-Coast, 74 Ancient Cornwall, 50–55 Penlee House Gallery & National Cycle Route, 75 Animal parks and Museum (Penzance), rentals, 75, 85, 87, sanctuaries 11, 43, 49, 129 165, 173 Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Round House & Capstan tours, 84–87 113 Gallery (Sennen Cove, Birding, -

Ref: LCAA1820

Ref: LCAA7727 £625,000 Cornerstone, Castle Horneck Road, Penzance, Cornwall, TR18 4TY FREEHOLD An immaculately presented, extended and refurbished detached modern house now impeccably presented and offering large open-plan living areas with 5 bedrooms (3 en-suite) together with a studio. All set in large, beautifully landscaped well stocked gardens, in all extending to approximately ¾ of an acre. 2 Ref: LCAA7727 SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION Ground Floor: reception hall, sitting room, conservatory, study, kitchen/dining room, utility room, master bedroom with en-suite dressing room and en-suite bathroom. Stair hall, guest bedroom 3 with en-suite shower room, 2 further bedrooms, family shower room. First Floor: bedroom 2 with en-suite bath/shower room. Outside: studio/gatehouse, bedroom, shower/hall and washroom. Large lawned garden with electric gated asphalted driveway sweeping up to a large parking area in front of the house. Store/workshop (originally part of a double garage, part of which is now being used as a utility room). Large three bay carport. Beautifully landscaped well planted gardens. Terracing to the front of the house with room for hot tub and steps down on to a large lawned front garden with well hedged boundaries. In all the grounds extend to approximately ¾ of an acre. DESCRIPTION A fantastically spacious and beautifully refurbished, extended, detached five bedroom dormer style house with the majority of the accommodation on the ground floor comprising large open-plan living spaces and excellent bedroom accommodation, sufficient for a large family. The entire property is impeccably presented having been refitted to an excellent standard. The accommodation comprises a superb open-plan sitting room with doors off to a large modern conservatory and a study. -

Warwickshire County Record Office

WARWICKSHIRE COUNTY RECORD OFFICE Priory Park Cape Road Warwick CV34 4JS Tel: (01926) 738959 Email: [email protected] Website: http://heritage.warwickshire.gov.uk/warwickshire-county-record-office Please note we are closed to the public during the first full week of every calendar month to enable staff to catalogue collections. A full list of these collection weeks is available on request and also on our website. The reduction in our core funding means we can no longer produce documents between 12.00 and 14.15 although the searchroom will remain open during this time. There is no need to book an appointment, but entry is by CARN ticket so please bring proof of name, address and signature (e.g. driving licence or a combination of other documents) if you do not already have a ticket. There is a small car park with a dropping off zone and disabled spaces. Please telephone us if you would like to reserve a space or discuss your needs in any detail. Last orders: Documents/Photocopies 30 minutes before closing. Transportation to Australia and Tasmania Transportation to Australia began in 1787 with the sailing of the “First Fleet” of convicts and their arrival at Botany Bay in January 1788. The practice continued in New South Wales until 1840, in Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania) until 1853 and in Western Australia until 1868. Most of the convicts were tried at the Assizes, The Court of the Assize The Assizes dealt with all cases where the defendant was liable to be sentenced to death (nearly always commuted to transportation for life. -

PDFHS CD/Download Overview 100 Local War Memorials the CD Has Photographs of Almost 90% of the Memorials Plus Information on Their Current Location

PDFHS CD/Download Overview 100 Local War Memorials The CD has photographs of almost 90% of the memorials plus information on their current location. The Memorials - listed in their pre-1970 counties: Cambridgeshire: Benwick; Coates; Stanground –Church & Lampass Lodge of Oddfellows; Thorney, Turves; Whittlesey; 1st/2nd Battalions. Cambridgeshire Regiment Huntingdonshire: Elton; Farcet; Fletton-Church, Ex-Servicemen Club, Phorpres Club, (New F) Baptist Chapel, (Old F) United Methodist Chapel; Gt Stukeley; Huntingdon-All Saints & County Police Force, Kings Ripton, Lt Stukeley, Orton Longueville, Orton Waterville, Stilton, Upwood with Gt Ravely, Waternewton, Woodston, Yaxley Lincolnshire: Barholm; Baston; Braceborough; Crowland (x2); Deeping St James; Greatford; Langtoft; Market Deeping; Tallington; Uffington; West Deeping: Wilsthorpe; Northamptonshire: Barnwell; Collyweston; Easton on the Hill; Fotheringhay; Lutton; Tansor; Yarwell City of Peterborough: Albert Place Boys School; All Saints; Baker Perkins, Broadway Cemetery; Boer War; Book of Remembrance; Boy Scouts; Central Park (Our Jimmy); Co-op; Deacon School; Eastfield Cemetery; General Post Office; Hand & Heart Public House; Jedburghs; King’s School: Longthorpe; Memorial Hospital (Roll of Honour); Museum; Newark; Park Rd Chapel; Paston; St Barnabas; St John the Baptist (Church & Boys School); St Mark’s; St Mary’s; St Paul’s; St Peter’s College; Salvation Army; Special Constabulary; Wentworth St Chapel; Werrington; Westgate Chapel Soke of Peterborough: Bainton with Ashton; Barnack; Castor; Etton; Eye; Glinton; Helpston; Marholm; Maxey with Deeping Gate; Newborough with Borough Fen; Northborough; Peakirk; Thornhaugh; Ufford; Wittering. Pearl Assurance National Memorial (relocated from London to Lynch Wood, Peterborough) Broadway Cemetery, Peterborough (£10) This CD contains a record and index of all the readable gravestones in the Broadway Cemetery, Peterborough. -

Cognition and Learning Schools List

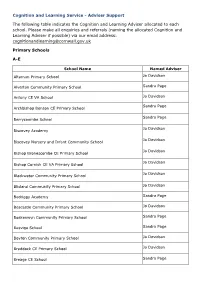

Cognition and Learning Service - Adviser Support The following table indicates the Cognition and Learning Adviser allocated to each school. Please make all enquiries and referrals (naming the allocated Cognition and Learning Adviser if possible) via our email address: [email protected] Primary Schools A-E School Name Named Adviser Jo Davidson Altarnun Primary School Sandra Page Alverton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Antony CE VA School Sandra Page Archbishop Benson CE Primary School Sandra Page Berrycoombe School Jo Davidson Biscovey Academy Jo Davidson Biscovey Nursery and Infant Community School Jo Davidson Bishop Bronescombe CE Primary School Jo Davidson Bishop Cornish CE VA Primary School Jo Davidson Blackwater Community Primary School Jo Davidson Blisland Community Primary School Sandra Page Bodriggy Academy Jo Davidson Boscastle Community Primary School Sandra Page Boskenwyn Community Primary School Sandra Page Bosvigo School Boyton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Jo Davidson Braddock CE Primary School Sandra Page Breage CE School School Name Named Adviser Jo Davidson Brunel Primary and Nursery Academy Jo Davidson Bude Infant School Jo Davidson Bude Junior School Jo Davidson Bugle School Jo Davidson Burraton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Callington Primary School Jo Davidson Calstock Community Primary School Jo Davidson Camelford Primary School Jo Davidson Carbeile Junior School Jo Davidson Carclaze Community Primary School Sandra Page Cardinham School Sandra Page Chacewater Community Primary -

Environmental Protection Final Draft Report

Environmental Protection Final Draft Report ANNUAL CLASSIFICATION OF RIVER WATER QUALITY 1992: NUMBERS OF SAMPLES EXCEEDING THE QUALITY STANDARD June 1993 FWS/93/012 Author: R J Broome Freshwater Scientist NRA C.V.M. Davies National Rivers Authority Environmental Protection Manager South West R egion ANNUAL CLASSIFICATION OF RIVER WATER QUALITY 1992: NUMBERS OF SAMPLES EXCEEDING TOE QUALITY STANDARD - FWS/93/012 This report shows the number of samples taken and the frequency with which individual determinand values failed to comply with National Water Council river classification standards, at routinely monitored river sites during the 1992 classification period. Compliance was assessed at all sites against the quality criterion for each determinand relevant to the River Water Quality Objective (RQO) of that site. The criterion are shown in Table 1. A dashed line in the schedule indicates no samples failed to comply. This report should be read in conjunction with Water Quality Technical note FWS/93/005, entitled: River Water Quality 1991, Classification by Determinand? where for each site the classification for each individual determinand is given, together with relevant statistics. The results are grouped in catchments for easy reference, commencing with the most south easterly catchments in the region and progressing sequentially around the coast to the most north easterly catchment. ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 110221i i i H i m NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY - 80UTH WEST REGION 1992 RIVER WATER QUALITY CLASSIFICATION NUMBER OF SAMPLES (N) AND NUMBER -

CORNWALL Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph CORNWALL Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No Parish Location Position CW_BFST16 SS 26245 16619 A39 MORWENSTOW Woolley, just S of Bradworthy turn low down on verge between two turns of staggered crossroads CW_BFST17 SS 25545 15308 A39 MORWENSTOW Crimp just S of staggered crossroads, against a low Cornish hedge CW_BFST18 SS 25687 13762 A39 KILKHAMPTON N of Stursdon Cross set back against Cornish hedge CW_BFST19 SS 26016 12222 A39 KILKHAMPTON Taylors Cross, N of Kilkhampton in lay-by in front of bungalow CW_BFST20 SS 25072 10944 A39 KILKHAMPTON just S of 30mph sign in bank, in front of modern house CW_BFST21 SS 24287 09609 A39 KILKHAMPTON Barnacott, lay-by (the old road) leaning to left at 45 degrees CW_BFST22 SS 23641 08203 UC road STRATTON Bush, cutting on old road over Hunthill set into bank on climb CW_BLBM02 SX 10301 70462 A30 CARDINHAM Cardinham Downs, Blisland jct, eastbound carriageway on the verge CW_BMBL02 SX 09143 69785 UC road HELLAND Racecourse Downs, S of Norton Cottage drive on opp side on bank CW_BMBL03 SX 08838 71505 UC road HELLAND Coldrenick, on bank in front of ditch difficult to read, no paint CW_BMBL04 SX 08963 72960 UC road BLISLAND opp. Tresarrett hamlet sign against bank. Covered in ivy (2003) CW_BMCM03 SX 04657 70474 B3266 EGLOSHAYLE 100m N of Higher Lodge on bend, in bank CW_BMCM04 SX 05520 71655 B3266 ST MABYN Hellandbridge turning on the verge by sign CW_BMCM06 SX 06595 74538 B3266 ST TUDY 210 m SW of Bravery on the verge CW_BMCM06b SX 06478 74707 UC road ST TUDY Tresquare, 220m W of Bravery, on climb, S of bend and T junction on the verge CW_BMCM07 SX 0727 7592 B3266 ST TUDY on crossroads near Tregooden; 400m NE of Tregooden opp. -

Britishness, What It Is and What It Could Be, Is

COUNTY, NATION, ETHNIC GROUP? THE SHAPING OF THE CORNISH IDENTITY Bernard Deacon If English regionalism is the dog that never barked then English regional history has in recent years been barely able to raise much more than a whimper.1 Regional history in Britain enjoyed its heyday between the late 1970s and late1990s but now looks increasingly threadbare when contrasted with the work of regional geographers. Like geographers, in earlier times regional historians busied themselves with two activities. First, they set out to describe social processes and structures at a regional level. The region, it was claimed, was the most convenient container for studying ‘patterns of historical development across large tracts of the English countryside’ and understanding the interconnections between social, economic, political, demographic and administrative history, enabling the researcher to transcend both the hyper-specialization of ‘national’ historical studies and the parochial and inward-looking gaze of English local history.2 Second, and occurring in parallel, was a search for the best boundaries within which to pursue this multi-disciplinary quest. Although he explicitly rejected the concept of region on the grounds that it was impossible comprehensively to define the term, in many ways the work of Charles Phythian-Adams was the culmination of this process of categorization. Phythian-Adams proposed a series of cultural provinces, supra-county entities based on watersheds and river basins, as broad containers for human activity in the early modern period. Within these, ‘local societies’ linked together communities or localities via networks of kinship and lineage. 3 But regions are not just convenient containers for academic analysis.