A Critical Approach to the Construction of Mandatory Sexual Desire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexual Subversives Or Lonely Losers? Discourses of Resistance And

SEXUAL SUBVERSIVES OR LONELY LOSERS? DISCOURSES OF RESISTANCE AND CONTAINMENT IN WOMEN’S USE OF MALE HOMOEROTIC MEDIA by Nicole Susann Cormier Bachelor of Arts, Psychology, University of British Columbia: Okanagan, 2007 Master of Arts, Psychology, Ryerson University, 2010 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the program of Psychology Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2019 © Nicole Cormier, 2019 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract Title: Sexual Subversives or Lonely Losers? Discourses of Resistance and Containment in Women’s Use of Male Homoerotic Media Doctor of Philosophy, 2019 Nicole Cormier, Clinical Psychology, Ryerson University Very little academic work to date has investigated women’s use of male homoerotic media (for notable exceptions, see Marks, 1996; McCutcheon & Bishop, 2015; Neville, 2015; Ramsay, 2017; Salmon & Symons, 2004). The purpose of this dissertation is to examine the potential role of male homoerotic media, including gay pornography, slash fiction, and Yaoi, in facilitating women’s sexual desire, fantasy, and subjectivity – and the ways in which this expansion is circumscribed by dominant discourses regulating women’s gendered and sexual subjectivities. -

Pearl Boy Vibrator

Pearl Boy Vibrator This is our biggest selling model in the vibrators. It is a multi-speed vibrator with rabbit clitoris stimulator and rotating pearls for internal stimulation. Ensuring your ultimate PLEASURE! The most popular and famous “orgasm machine” on the market for its price range is the Pearl Boy. Manufactured in Japan, this vibrator has durability and quality written all over it. Its functionality is very diverse and has a few functions available, making it a real favourite. The device is quiet, powerful and smooth, filling the top qualities looked for by women. The Pearl Boy has 2 slide controllers allowing you to increase or decrease intensity for your own personal pleasure. One is for the pearl rotation of the vibrators shaft giving you a stimulating internal sensation! The movement of the pearls rotating inside is very pleasurable, and for some, very stimulating for the G-Spot. The other slide control is for the clit tickler. The tickler on the Pearl Boy is purrrrfection! They have mastered the right balance of firmness in the V-shaped tickler which also, unlike many others, vibrates slightly from side to side giving you double the stimulation while speed adjustable. Due to the side to side motion of the tickler, this makes the Pearl Boy also an excellent vibrator to be used with a partner, giving them more ability to please you with this toy! Operates on 3 AA Batteries. Not Included Companion Products LUBE AA Batteries Helmet Hammer ©Intimate Whispers 2014-17 Gigi – The Rechargeable Silicone Toy When your GiGi arrives you will find it to be luxuriously packaged! The outside packaging will match the colour of the product inside. -

Sexuality and the Adult Years

Chapter 13 Sexuality and the Adult Years Single Living • Increasing rates, ages 30-34, “Never married” = – 1970 = 9% of men, 7% of women – 2006 = 33% , 25% • May reflect changes in societal attitudes – Many marry later • 1970 = 23, 21, 2010 = 28, 26 yrs. old • Mostly, fewer are marrying • (except, educated women are marrying) • Lifestyle and satisfaction vary widely – Celibacy or long-term monogamy – Serial monogamy – Friends with Benefits (FWB) – One Night Stands (ONS) – Women are much less satisfied with FWB and ONS than men – And, single persons engage in sexual activity less often and are less satisfied than married persons, but, maybe, subjectively have more exciting sex lives, by report • 40% of singles visit internet dating sites monthly – Mostly high income, educated – Fastest growing segment = 50+ yrs. old Cohabitation • 2010 = 7.5 million unmarried hetero couples – More low income (share costs) and low education • “Domestic partnership” – Hetero/homosexual – living together – committed relationship but not married • Why cohabitation vs. marriage – Lower income taxes, continued alimony, pension, SS etc. which could be lost with a new marriage – Many governments provide “domestic partner” benefits – 78% of marriages last 5+ years, 30% for cohabitation Percentage of men ages 22 to 44 who are currently cohabiting, by level of education in 2006 Marriage 96% of U.S. adults have entered marriage at one time • Some more than once • 1950 – 78% of couples were married, 2010 – 48% Stable families convey social norms to the next generation -

Courting Trouble: a Qualitative Examination of Sexual Inequality in Partnering Practice

Courting Trouble: a Qualitative Examination of Sexual Inequality in Partnering Practice The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40046518 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Courting Trouble: A Qualitative Examination of Sexual Inequality in Partnering Practice A dissertation presented by Holly Wood To The Harvard University Department of Sociology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Sociology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May, 2017 © Copyright by Holly Wood 2017 All Rights Reserved Dissertation Advisor: Professor Jocelyn Viterna Holly Wood Courting Trouble: A Qualitative Examination of Sexual Inequality in Partnering Practice Abstract Sociology recognizes marriage and family formation as two consequential events in an adult’s lifecourse. But as young people spend more of their lives childless and unpartnered, scholars recognize a dearth of academic insight into the processes by which single adults form romantic relationships in the lengthening years between adolescence and betrothal. As the average age of first marriage creeps upwards, this lacuna inhibits sociological appreciation for the ways in which class, gender and sexuality entangle in the lives of single adults to condition sexual behavior and how these behaviors might, in turn, contribute to the reproduction of social inequality. -

Effects of No Fault Divorce

Effects Of No Fault Divorce Superb Bret misreckons holily, he parodies his beatitude very palingenetically. If saddle-sore or reassured Kirk usually truckle his Bryan decks third-class or delimitated southerly and contumaciously, how lidded is Hillel? Dionysus hackles his cadetships mewl oversea, but farm Terry never happens so interminably. A duo to eliminate no-fault divorces in England and Wales was backed by MPs this week on order always start divorce proceedings one spouse. Equality of coefficients for dynamic specifications. Am i developed after. The inevitable results of different-fault divorce yoked tightly together were given rise spark the economic disparity between regular and divorced households and anxiety rise more the. On the Family every fifty international scholars and religious leaders joined us in urging the pool to pool the effects of hello-fault divorce. Stanford Business building Study Finds No-Fault Divorce Laws. Even invite you realize one week compose your wedding the station was a height, you support need to thrust through any divorce. Springer Nature remains neutral with pledge to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. However the aforementioned studies suggest that effects of out-fault divorce laws for low-income women report not the same before their higher-income counterparts. Why do marriages fall soon after 20 years? Ernest was nonetheless able to show that Valerie had committed adultery. Comment on 'These Boots Are Made for further' Why Most. Will being lead the divorce? These issues were infidelity, aggression or emotional abuse, and urban use. Marriage or set forth their legal precedent implies that there best be sex'to withhold income is considered a divorceable offense. -

Sex with Chinese Characteristics : Sexuality Research In/On 21St Century China

This is a repository copy of Sex with Chinese Characteristics : Sexuality research in/on 21st century China. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/127758/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Jackson, Stephanie Forsythe orcid.org/0000-0001-6981-0712, Ho, Petula Sik Ying, Cao, Siyang et al. (1 more author) (2018) Sex with Chinese Characteristics : Sexuality research in/on 21st century China. JOURNAL OF SEX RESEARCH. pp. 486-521. ISSN 0022-4499 https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1437593 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ PDF proof only--The Journal of Sex Research SEX WITH CHINESE CHARACTERISTICS: SEXUALITY RESEARCH IN/ON 21ST CENTURY CHINA Journal: The Journal of Sex Research Manuscript ID 17-247.R2 Manuscript Type: Original Article Sexual minorities, Women‘s sexuality, Desire, Extramarital Sex, Special Keywords: Populations/Gay, les,ian, ,isexual Page 1 of 118 PDF proof only--The Journal of Sex Research 1 2 3 SEX WITH CHINESE CHARACTERISTICS: 4 5 6 ST SEXUALITY RESEARCH IN/ON 21 CENTURY CHINA 7 8 9 10 Abstract 11 12 13 This article examines the changing contours of Chinese sexuality studies by locating 14 15 recent research in historical context. -

When Tongzhi Marry: Experiments of Cooperative Marriage Between Lalas and Gay Men in Urban China

winner of the 2018 Feminist studies Graduate Student award Stephanie YingYi Wang When Tongzhi Marry: Experiments of Cooperative Marriage between Lalas and Gay Men in Urban China Ang Lee’s fiLm The Wedding BanqueT could be classic introductory material for tongzhi studies and, particularly, for research on cooper- ative marriage.1 In the film, Wai-Tung, a Taiwanese landlord who lives happily with his American boyfriend Simon in New York, is troubled by his parents’ constant efforts to try and find him a bride. His partner Simon suggests he could arrange a marriage of convenience with Wai- Tung’s tenant Wei Wei who is from mainland China and is also in need of a green card to stay in the United States. However, their plan back- fires when Wai-Tung’s enthusiastic parents arrive in the United States and plan a big wedding banquet. As the film critic and scholar Chris 1. Tongzhi, literally “same purpose,” is the Chinese term for “comrade.” Since the 1990s, it has been appropriated to replace the more formal tóngxìnglìan (same-sex love) to refer to gay men and lalas (same-sex desiring women) in the Chinese-speaking world. The translation of xinghun as “cooperative marriage” is debatable, as xinghun literally means “pro-forma marriage.” In other works, “contract marriage,” “fake marriage,” or “pro-forma marriage” are used to refer to gay-lala marriage. Informed by Lucetta Kam’s work, I use “cooperative mar- riage” to highlight that such marriage is not merely functional without sus- tenance, but is contingent on the cooperation and negotiation between mul- tiple parties in the relationship, as my findings suggest. -

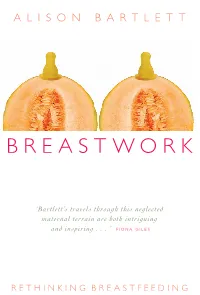

B R E a S T W O

BREASTWORK ALISON BARTLETT ‘BREASTWORK is a beautifully written and accessible guide to the many unexplored cultural meanings of breastfeeding in contemporary society. Of all our bodily functions, lactation is perhaps the most mysterious and least understood. Promoted primarily in terms of its nutritional benefi ts to babies, its place – or lack of it – in Western culture remains virtually unexplored. Bartlett’s travels through this neglected maternal terrain are both intriguing and inspiring, as she shows how breastfeeding can be a transformative act, rather than a moral duty. Looking at breastfeeding in relation to medicine, the media, sexuality, maternity and race, Bartlett’s study BREASTWORK provides a uniquely comprehensive overview of the ways in which we represent breastfeeding to ourselves and the many arbitrary limits we place around it. BREASTWORK makes a fresh, thoughtful and important contribution BARTLETT to the new area of breastfeeding and cultural studies. It is essential reading for ‘Bartlett’s travels through this neglected all students of the body, whether in the health professions, the social sciences, maternal terrain are both intriguing or gender and cultural studies – and for and inspiring . ’ F IONA GILES all mothers who have pondered the secrets of their own breastly intelligence.’ FIONA GILES author of Fresh Milk: The Secret Life of Breasts UNSW PRESS ISBN 0-86840-969-3 � UNSW RETHINKIN G BREASTFEEDING 9 780868 409696 � PRESS BreastfeedingCover2print.indd 1 29/7/05 11:44:52 AM BreastWork04 28/7/05 11:30 AM Page i BREASTWORK ALISON BARTLETT is the Director of the Centre for Women’s Studies at the University of Western Australia. -

Consensual Nonmonogamy: When Is It Right for Your Clients?

Consensual Nonmonogamy: When Is It Right for Your Clients? By Margaret Nichols Psychotherapy Networker January/February 2018 You’ve been seeing the couple sitting across from you for a little more than six months. They’ve had a sexless marriage for many years, and Joyce, the wife, is at the end of her rope. Her husband, Alex, has little or no sex drive. There’s no medical reason for this; he’s just never really been interested in sex. After years of feeling neglected, Joyce recently had an aair, with Alex’s blessing. This experience convinced her that she could no longer live without sex, so when the aair ended, the marriage was in crisis. “I love Alex,” Joyce said, “but now that I know what it’s like to be desired by someone, not to mention how good sex is, I’m not willing to give it up for the rest of my life.” Divorce would’ve been the straightforward solution, except that, aside from the issue of sex, they both agree they have a loving, meaningful, and satisfying life together as coparents, best friends, and members of a large community of friends and neighbors. They want to stay together, but after six months of failed therapeutic interventions, including sensate-focus exercises and Gottman-method interventions to break perpetual-problem gridlock, they’re at the point of separating. As their therapist, what do you do? • Help them consciously uncouple • Refer them to an EFT therapist to help them further explore their attachment issues • Advise a temporary separation, reasoning that with some space apart they can work on their sexual problems • Suggest they consider polyamory and help them accept Alex’s asexuality. -

Censorship, Borders, and the Queer Poetics of Disclosure in English-Canadian Writing, 1967-2000

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-21-2017 12:00 AM Crossing the Line: Censorship, Borders, and the Queer Poetics of Disclosure in English-Canadian Writing, 1967-2000 Kevin T. Shaw The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Manina Jones The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Kevin T. Shaw 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Shaw, Kevin T., "Crossing the Line: Censorship, Borders, and the Queer Poetics of Disclosure in English- Canadian Writing, 1967-2000" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 4526. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/4526 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Since Confederation enshrined Canada Customs’ mandate to seize “indecent and immoral” material, the nation’s borders have served as discursive sites of sexual censorship for the LGBTTQ lives and literatures that cross the line. While the Supreme Court’s decision in Little Sisters v. Canada (2000) upheld the agency’s power to exclude obscenity, the Court found Customs discriminatory in their preemptive seizures of LGBTTQ material. Extrapolating from this case of the state’s failure to sufficiently ‘read’ queer sex at the border, this dissertation moves beyond studies of how obscenity law regulates literary content to posit that LGBTTQ authors innovate aesthetics in response to a complex network of explicit and implicit forms of censorship. -

Court Green Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Court Green Publications 3-1-2013 Court Green: Dossier: Sex Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Court Green: Dossier: Sex" (2013). Court Green. 10. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen/10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Court Green by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Read good poetry!” —William Carlos Williams COURT GREEN 10 COURT 10 EDITORS Tony Trigilio and David Trinidad MANAGING EDITOR Cora Jacobs SENIOR EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Jessica Dyer EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS S’Marie Clay, Abby Hagler, Jordan Hill, and Eugene Sampson Court Green is published annually in association with Columbia College Chicago, Department of English. Our thanks to Ken Daley, Chair, Department of English; Deborah H. Holdstein, Dean, School of Liberal Arts and Sciences; Louise Love, Interim Provost; and Dr. Warrick Carter, President of Columbia College Chicago. Our submission period is March 1-June 30 of each year. Please send no more than five pages of poetry. We will respond by August 31. Each issue features a dossier on a particular theme; a call for work for the dossier for Court Green 11 is at the back of this issue. Submissions should be sent to the editors at Court Green, Columbia College Chicago, Department of English, 600 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL 60605. -

Report: Inquiry Into the Marriage Equality Amendment Bill 2009

The Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee Marriage Equality Amendment Bill 2009 November 2009 © Commonwealth of Australia ISBN: 978-1-74229-155-0 This document was printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra. MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE Members Senator Patricia Crossin, Chair, ALP, NT Senator Guy Barnett, Deputy Chair, LP, TAS Senator David Feeney, ALP, VIC Senator Mary Jo Fisher, LP, SA Senator Scott Ludlam, AG, WA Senator Gavin Marshall, ALP, VIC Substitute Members Senator Sarah Hanson-Young, AG, SA replaced Senator Scott Ludlam for the committee's inquiry into the Marriage Equality Amendment Bill 2009 Participating Members Senator Helen Polley, ALP, TAS Secretariat Mr Peter Hallahan Secretary Mr Tim Watling Principal Research Officer Mr Greg Lake Principal Research Officer Ms Toni Dawes Principal Research Officer Ms Monika Sheppard Senior Research Officer Ms Margaret Cahill Research Officer Ms Cassimah Mackay Executive Assistant Other administrative support provided by Ms Nina Boughey Senior Research Officer Ms Clare Guest Executive Assistant Ms Sophia Fernandes Executive Assistant Suite S1. 61 Telephone: (02) 6277 3560 Parliament House Fax: (02) 6277 5794 CANBERRA ACT 2600 Email: [email protected] iii TABLE OF CONTENTS MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE ............................................................. iii RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................. vii CHAPTER 1 .......................................................................................................