Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 & 2 Samuel Series Lesson #176

1 & 2 Samuel Series Lesson #176 June 25, 2019 Dean Bible Ministries www.deanbibleministries.org Dr. Robert L. Dean, Jr. LEVIATHAN, TANNIN, AND RAHAV–PART 3 2 SAMUEL 7:18–29; PSALM 89:10 What the Bible Teaches About The Davidic Covenant Psa. 89:10, “You have broken Rahab in pieces, as one who is slain; You have scattered Your enemies with Your mighty arm.” comm masc sing abs Rahab, Rahav רהַב proper Rahab, literally, Rachav, name רָ חָב This term shows up in in Job 9:13; Job 26:12; Psalm 89:10; Isaiah 51:9. TWOT describes the verbal form in this manner: The basic meaning of the noun is arrogance. Rahav, can best be translated as “the arrogant one.” 1. God created all living things including Rahav, leviathan, behemoth, the sea, and the tannin. These are real, not mythological creatures and creation. 2. God in His omniscience designed all of these things. Their design was intentional, with a view to how they would be used as biblical symbols as well as mythological representations. Tracing these “sea monsters” 1. Yam 2. Tannin 3. Leviathan 4. Rahav 5. Behemoth GOD the Creator Mythological Deities All creatures: Yam, Leviathan, Behemoth, Tannin, Rahav designed with a purpose Uses God’s creatures to represent pagan deities [demons] and to describe origin myths. Referred to in the Bible: 1. As actual, historical creatures, and also 2. with a view to their mythological connotations to communicate God vs. evil. Job 9:13, “God will not turn back His anger; Beneath Him crouch the helpers of Rahav.” [NKJV: allies of the proud] Isa. -

Sea Monsters and Real Environmental Threats: Reconsidering the Famous Osborne, ‘Moha-Moha’, Valhalla, and ‘Soay Beast’ Sightings of Unidentified Marine Objects

IMAGINARY SEA MONSTERS AND REAL ENVIRONMENTAL THREATS: RECONSIDERING THE FAMOUS OSBORNE, ‘MOHA-MOHA’, VALHALLA, AND ‘SOAY BEAST’ SIGHTINGS OF UNIDENTIFIED MARINE OBJECTS R. L. FRANCE Dal Ocean Research Group Department of Plant, Food, and Environmental Sciences, Dalhousie University Abstract At one time, largely but not exclusively during the nineteenth century, retellings of encounters with sea monsters were a mainstay of dockside conversations among mariners, press reportage for an audience of fascinated landlubbers, and journal articles published by believing or sceptical natural scientists. Today, to the increasing frustration of cryptozoologists, mainstream biologists and environmental historians have convincingly argued that there is a long history of conflating or misidentifying known sea animals as purported sea monsters. The present paper provides, for the first time, a detailed, diachronic review of competing theories that have been posited to explain four particular encounters with sea monsters, which at the time of the sightings (1877, 1890, 1905, and 1959) had garnered worldwide attention and considerable fame. In so doing, insights are gleaned about the role played by sea monsters in the culture of late-Victorian natural science. Additionally, and most importantly, I offer my own parsimonious explanation that the observed ‘sea monsters’ may have been sea turtles entangled in pre-plastic fishing gear or maritime debris. Environmental history is therefore shown to be a valuable tool for looking backward in order to postulate the length of time that wildlife populations have been subjected to anthropogenic pressure. This is something of contemporary importance, given that scholars are currently involved in deliberations concerning the commencement date of the Anthropocene Era. -

From Indo-European Dragon Slaying to Isa 27.1 a Study in the Longue Durée Wikander, Ola

From Indo-European Dragon Slaying to Isa 27.1 A Study in the Longue Durée Wikander, Ola Published in: Studies in Isaiah 2017 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Wikander, O. (2017). From Indo-European Dragon Slaying to Isa 27.1: A Study in the Longue Durée. In T. Wasserman, G. Andersson, & D. Willgren (Eds.), Studies in Isaiah: History, Theology and Reception (pp. 116- 135). (Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament studies, 654 ; Vol. 654). Bloomsbury T&T Clark. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 LIBRARY OF HEBREW BIBLE/ OLD TESTAMENT STUDIES 654 Formerly Journal of the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series Editors Claudia V. -

Worthless Deities in the Hebrew Text

Worthless Deities Listed in the Hebrew Text by Kathryn QannaYahu I would like to thank my daughters Leviyah and Genevieve for their support, both encouragement and financial so that I could work on this study full time. I would also like to thank the Bozeman Public Library, especially Mary Ann Childs, who handled well over a hundred of my interlibrary loans during these two years. Subcategory Links Foreign Language Intro Study Intro Proto-Indo-Europeans and the Patriarchy From Clan Mother To Goddess Ancestor Worship/Cult of the Dead Therafiym Molek/Melek Nechushthan and Sherafiym Astral Cult Seal of God – Mark of the Beast Deities Amurru / Amorite Ugaritic / Canaanite Phoenician / Felishthiym [Philistine] / Carthaginian Syrian / Aramean Babylonian / Assyrian Map of Patron Deity City Names Reference Book List Foreign Language Intro This study incorporates many textual elements that need their own introduction because of all the languages presented. For the Hebrew, I use a Hebrew font that you will not be able to view without a download, unless you happen to have the font from another program. If you should see odd letters strung together where a name or word is being explained, you probably need the font. It is provided on my fonts page http://www.lebtahor.com/Resources/fonts.htm . Since Hebrew does not have an upper and lower case, another font used for the English quoting of the Tanak/Bible is the copperplate, which does not have a case. I use this font when quoting portions of the Tanak [Hebrew Bible], to avoid translator emphasis that capitalizing puts a slant on. -

An Example Reinterpreting the British Isles' Most Detailed Account of a Sea Serpent Sight

RESEARCH ARTICLE Ethnobiology and Conservation 2019, 8:12 (12 October 2019) doi:10.15451/ec2019-10-8.12-1-31 ISSN 22384782 ethnobioconservation.com Ethnobiology and Shifting Baselines: An Example Reinterpreting the British Isles’ Most Detailed Account of a Sea Serpent Sighting as Early Evidence for PrePlastic Entanglement of Basking Sharks Robert L. France ABSTRACT Recognizing shifts in baseline conditions is necessary for understanding longterm changes in populations as a prelude to implementing presentday management actions and setting future restoration goals for anthropogenicallyaltered marine ecosystems. Examining historical information contained within anecdotal accounts from nontraditional sources has previously proven useful in this regard. Herein, I scrutinize eyewitness accounts and accompanying illustrations published in nineteenthcentury natural history journals which together comprise the most detailed description of sighting a purported sea serpent in the British Isles. I then reinterpret this anecdote (as well as complementary evidence offered by cryptozooloogists in its support obtained from other published journal articles of similarly described unidentified marine objects), suggesting it to provide one of the earliest reports of the nonlethal entanglement of an animal—in this case what I believe to have been a basking shark—in European waters. The present work suggests that the entanglement of sharks in fishing gear or hunting equipment has a much longer environmental history than is commonly believed, and provides another example of how ethnozoological studies can contribute toward recognizing past fishingrelated pressures and baseline shifts in affected populations. Sharks, it seems, have been subjected to the impacts of not just direct fishery exploitation but also through becoming bycatch, long before the advent and widespread use of plastic in the middle of the twentieth century. -

Water Resources

L-- I; Ii II II Ii II II II II II II Strait of Canso II Ii Natural Environment Inventory I: II Water Resources I; commissioned by The Canada-Nova Scotia Strait of Canso EnvironmentCommittee II 1975 " II " ., I Reports printed by Earl Whynot & Associates Limited, Halifax, Nova Scotia Maps printed by Montreal Lithographing Limited, Montreal, Quebec ] "j c- FOREWORD An exchange of letters in 1973 between the Ministers of the Environment for Nova Scotia and for Canada identified the need for an environmental assessment of the Strait of Canso region and established the Canada-Nova Scotia Strait of Canso Environment Committee. The Committee is composed of representatives of the Department of Regional Economic Expansion, Environment Canada and Transport Canada, and of the Department of the Environment, Department of Development and Department of Municipal Affairs of the Province of Nova Scotia. The Strait of Canso Environment Committee has as its first objective the development of an environmental management strategy proposal for the Strait of Canso area. Regional environmental assessment and environmental management programs must necessarily be based upon a comprehensive and integrated knowledge of the physical, social and economic resource base ofthe region. Toward this end, the Committee arranged for an initial program, funded under a Federal-Provincial agreement, comprising an inventory of existing information on the natural environment of the Strait of Canso region. The inventory of natural resources and resource uses commenced the summer of 1974, leading to the presentation of the information in a series of special maps and accompanying reports for publication and distribution in late 1975 and early 1976. -

Tolkien's Treatment of Dragons in Roverandom and Farmer Giles of Ham

Volume 34 Number 1 Article 8 10-15-2015 "A Wilderness of Dragons": Tolkien's Treatment of Dragons in Roverandom and Farmer Giles of Ham Romuald I. Lakowski MacEwan University in Edmonton, Canada Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lakowski, Romuald I. (2015) ""A Wilderness of Dragons": Tolkien's Treatment of Dragons in Roverandom and Farmer Giles of Ham," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 34 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol34/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract An exploration of Tolkien’s depictions of dragons in his stories for children, Roverandom and Farmer Giles of Ham. Draws on “On Fairy-stories,” the Beowulf lecture, the Father Christmas letters, and a little-known “Lecture on Dragons” Tolkien gave to an audience of children at the University Museum in Oxford, as well as source Tolkien would have known: Nennius, The Fairy Queene, and so on. -

Port Hawkesbury Looking Back

Port Hawkesbury Looking Back... CONNECTING LITERACY AND COMMUNITY Port Hawkesbury Literacy Council June 2002 Our sincere thanks to the National Literacy Secretariat, Human Resources Development Canada for providing funding for this project. Acknowledgements This book is a project of the Port Hawkesbury Literacy Council which recognized the need for relevant adult learning material that was written for Level 1 and 2 learners in our CLI Adult Learning Program. The creation of this material would not have been possible without the support of the Port Hastings Museum staff. A thank you to them for the use of their many resources. A special thank you to the Port Hawkesbury Centennial Committee for permission to use material found in their invaluable resource, A Glimpse of the Past. Thanks also to the Tamarac Education Center Library for sharing their resources. Learners, Instructors, and Tutors from the Port Hawkesbury Community Learning Initiative Levels 1 and 2 took part in the planning and piloting of this material. A sincere thanks for their interest and input. Thanks, as well, to Bob Martin of Bob Martin Photographic Studios for the use, and copies, of his collection of Port Hawkesbury photographs and to Pat MacKinnion for the use of the beautiful colour picture on the cover. Thanks as well to the staff of the Town of Port Hawkesbury for their administrative assistance; to the Port Hawkesbury Parks, Recreation and Tourism Department for their ongoing support of literacy in our area; to the members and staff of the Port Hawkesbury Literacy Council for their continued support; and to the Nova Scotia Department of Education, Adult Education Section, for their ongoing support. -

Adobe PDF File

BOOK REVIEWS Tony Tanner (ed.). The Oxford Book of Sea Allan Poe's "Descent into the Maelstrom," and Stories. New York & Toronto: Oxford Univer• H.G. Wells' "In the Abyss," imagine the terrors sity Press, 1994. xviii + 410 pp. $36.95, cloth; and mysteries of the sea in tales of supernatural ISBN 0-19-214210-0. moment. E.M. Forster's "The Story of the Siren" and Malcom Lowry's "The Bravest Boat" The sea assumes a timeless presence in this present a gentle contrast to these adventures collection of fiction from Oxford. Tony Tanner through their writers' rendering of lives attuned has selected a diverse assortment of stories by to the sea's rhythms. But the true gems in the well-known British, American and Canadian book, possibly the best ever written in the genre, writers. Through his editing, he emphasizes the Conrad's "The Secret Sharer" and Stephen eternal quality of the tales at the expense of Crane's "The Open Boat," bridge these two historical and social contexts, presenting stories forms, focusing in lyrical fashion on their involving sailors and landlubbers alike. The narrators' moral dilemmas within the intrigue of selections are arranged roughly chronologically, the adventure plots. encompassing the period from 1820 to 1967, As this list indicates, Tanner has selected and amply representing Great Britain (fifteen tales that will appeal to romantics and realists stories) and the United States (eleven stories). alike, but his interest is clearly aesthetic, not Canada gets short shrift, with only Charles G.D. historical. His muse in this regard seems to be Roberts, an odd choice, represented. -

How to Tell a Sea Monster: Molecular Discrimination of Large Marine Animals of the North Atlantic

Reference: Biol. Bull. 202: 1–5. (February 2002) How To Tell a Sea Monster: Molecular Discrimination of Large Marine Animals of the North Atlantic S. M. CARR1,*, H. D. MARSHALL1, K. A. JOHNSTONE1, L. M. PYNN1, AND G. B. STENSON2 1Genetics, Evolution, and Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Department of Biology, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Newfoundland A1B 3X9, Canada; and 2Marine Mammals Section, Science, Oceans, and Environment Branch, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, PO Box 5667, St. John’s, Newfoundland A1C 5X1, Canada “Either we do know all the varieties of beings which people our planet, or we do not. If we do not know them all—if Nature has still secrets in the deeps for us, nothing is more conformable to reason than to admit the existence of fishes, or cetaceans of other kinds, or even of new species ...which an accident of some sort has brought at long intervals to the upper level of the ocean.” —Jules Verne, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, 1870 Abstract. Remains of large marine animals that wash (1994) gives a contemporary list. Even in the first year of a onshore can be difficult to identify due to decomposition new century when the complete human genome has become and loss of external body parts, and in consequence may be known (International Human Genome Sequencing Consor- dubbed “sea monsters.” DNA that survives in such car- tium, 2001), the possibility that entirely new, previously casses can provide a basis of identification. One such crea- unknown species may unexpectedly present themselves re- ture washed ashore at St. -

N: a Sea Monster of a Research Project

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects Honors Program 5-2019 N: A Sea Monster of a Research Project Adrian Jay Thomson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Thomson, Adrian Jay, "N: A Sea Monster of a Research Project" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. 424. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/424 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. N: A SEA MONSTER OF A RESEARCH PROJECT by Adrian Jay Thomson Capstone submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with UNIVERSITY HONORS with a major in English- Creative Writing in the Department of English Approved: UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT SPRING2019 Abstract Ever since time and the world began, dwarves have always fought cranes. Ever since ships set out on the northern sea, great sea monsters have risen to prey upon them. Such are the basics of life in medieval and Renaissance Scandinavia , Iceland, Scotland and Greenland, as detailed by Olaus Magnus' Description of the Northern Peoples (1555) , its sea monster -heavy map , the Carta Marina (1539), and Abraham Ortelius' later map of Iceland, Islandia (1590). I first learned of Olaus and Ortelius in the summer of 2013 , and while drawing my own version of their sea monster maps a thought hit me: write a book series , with teenage characters similar to those in How to Train Your Dragon , but set it amongst the lands described by Olaus , in a frozen world badgered by the sea monsters of Ortelius. -

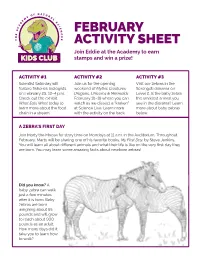

FEBRUARY ACTIVITY SHEET Join Eddie at the Academy to Earn Stamps and Win a Prize!

FEBRUARY ACTIVITY SHEET Join Eddie at the Academy to earn stamps and win a prize! ACTIVITY #1 ACTIVITY #2 ACTIVITY #3 Scientist Saturday will Join us for the opening Visit our zebras in the feature fisheries biologists weekend of Mythic Creatures: Serengeti diorama on on February 23, 12–4 p.m. Dragons, Unicorns & Mermaids Level 2. Is the baby zebra Check out the exhibit February 16–18 where you can the smallest animal you What Eats What today to watch as we dissect a “kraken” see in the diorama? Learn learn more about the food at Science Live. Learn more more about baby zebras chain in a stream. with the activity on the back. below. A ZEBRA’S FIRST DAY Join Marty the Moose for story time on Mondays at 11 a.m. in the Auditorium. Throughout February, Marty will be sharing one of his favorite books, My First Day, by Steve Jenkins. You will learn all about different animals and what their life is like on the very first day they are born. You may learn some amazing facts about newborn zebras! Did you know? A baby zebra can walk just a few minutes after it is born. Baby zebras are born weighing about 65 pounds and will grow to reach about 900 pounds as an adult. How many days did it take you to learn how to walk? MEMBER Don’t forget your stamp. Get your monthly stamp at the admissions desks. If you have eight stamps, it’s time to collect your prize in the Academy Shop! ansp.org 4/13/18 5:38 PM ANS_Kids_Club_Membership_Card.indd 1 RELEASE THE KRAKEN There are legends written about a sea monster called the Kraken.