FERA GA Online Series Session 1 October 6 2020 Transcription

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Mujer Es Cosa De Hombres-Isabel Coixet

50 años de... - La mujer, cosa de hombres. Isabel Coixet. Corto dirigido por Isabel Coixet en torno al tradicional papel de la mujer en la sociedad española y la repercusión que tienen en los medios los delitos por violencia de género. http://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/50-anos-de/50-anos-mujer-cosa- hombres/1491834/ Isabel Coixet nació en Sant Adrià del Besós el 9 de abril de 1960. Estudió Historia Contemporánea en la Universidad de Barcelona, trabajó como periodista en la revista Fotogramas . Su afición a la imagen le hace acercarse al mundo del cine, desempeñando diversas tareas y al mundo de la publicidad en el que, tras un tiempo, creará productora propia. Años más tarde, decidida a filmar su primer largometraje, se traslada a Estados Unidos a rodar Cosas que nunca te dije (1996). Un año después, nace su hija Zoe. Es un peso pesado de la industria publicitaria, y dirigió anuncios por todo el mundo: ha sido directora creativa de la agencia JWT, fundadora y directora creativa de la agencia Target y la productora Eddie Saeta, obteniendo los más prestigiosos premios por sus trabajos en este campo. En el año 2000 creó la productora Miss Wasabi Films desde donde también ha realizado destacados documentales -y vídeo clips a los más variados músicos En 2005 realiza La vida secreta de las palabras cuyos protagonistas son Tim Robbins y Sarah Polley. En 2006 formó, junto a otras cineastas como Inés París, Chus Gutiérrez o Icíar Bollaín, CIMA (Asociación de mujeres cineastas y de medios audiovisuales). Isabel ha contado con Penélope Cruz para el papel protagonista de su película Elegy, estrenada en 2008, y basada en una novela de Philip Roth. -

Marta Díaz De Lope Díaz: a Conversation with the Filmmaker

This work is on a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Access to this work was provided by the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) ScholarWorks@UMBC digital repository on the Maryland Shared Open Access (MD-SOAR) platform. Please provide feedback Please support the ScholarWorks@UMBC repository by emailing [email protected] and telling us what having access to this work means to you and why it’s important to you. Thank you. 1 The Passion of Marta Díaz de Lope Díaz: A Conversation with the Filmmaker In her directorial debut, Ronda native Marta Díaz de Lope Díaz takes inspiration from the cartography of her origin for her filmic vision. Her cultural roots anchor her life and filmography, that she has been perfecting over the years of her study and teaching at the ESCAC film school in Barcelona. Her first feature-length film, Mi querida cofradía (Hopelessly Devout), clearly reflects this influence since it drinks and revels in the most traditional celebration of her hometown: Holy Week. Likewise, as can be seen in this interview, the feature establishes an interesting parallel between the passion of the protagonist Carmen (Gloria Muñoz) to realize her dream of leading her Catholic brotherhood and the aspiration of its own Marta Díaz to become a film director. With humor, her cinema masterfully delves into the experiences of women, of their sisterhood, in both the private and public spheres, displaying the obstacles that they encounter when trying to fulfill their goals in a man’s world and exhibiting their skills at overcoming interference. -

Walter Salles

Selenium Films / A Contracorriente films / Altiro Films Original title: “La contadora de películas” A film by Isabel Coixet Screenplay by Walter Salles & Isabel Coixet Based on the novel «La Contadora de Películas» of Hernán Rivera Letelier This is the captivating story of Maria Margarita, The story develops hand in hand with a young girl who lives in a mining town nestled relevant cultural events in the history of in the heart of Chile's Atacama Desert in the the town, like the arrival and success of 60s. She has a very special gift — an almost un- cinema exhibition, followed by its decline canny ability to retell movies. Her talent and as the TV arrives. On a broader passion soon spread beyond her impoverished perspective, ‘The Movie-Teller’ portrays the family circle — five siblings and their disabled decay of the historical salt-peter mining father confined to a wheel-chair, who can only towns in the North of Chile. The film afford a ticket for one at the local movie thea- reveals the untold memories buried deep tre— to reach the whole community. People get in our historical roots; we are taught how together to listen Maria Margarita with delight all the dreams and hopes of ordinary and amusement, so they can forget the harsh people are ultimately subjected to the routines of their day-to-day lives. tyranny of fate. « I was immediately touched « It has all the elements by its profound humanity, that fascinate me and that by the innate capacity to blend make me love cinema humor and drama, and, of course, above all things » by its utter passion for film » _ _ Isabel Coixet Walter Salles Production storytelling. -

SEATTLE SEATTLE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL for More Information Go To

NEWS FROM EGEDA US Phone: 310 246 0531 Fax: 310 246 1343 Email: [email protected] SPANISH MOVIES IN USA – JUNE 2013 LOS ANGELES LOS ANGELES INTERNATIONAL FILM FEST For more information go to http://filmguide.lafilmfest.com/tixSYS/2013/xslguide/eventnote.php?EventNumber=5446 I’m So Excited! Thu, June 13 – 7:30 PM (Opening Night) at Regal Cinemas, 1000 W. Olympic Blvd. Dir. Pedro Almodovar - Spain|2012|90 min. Cast: Antonio de la Torre, Hugo Silva, Miguel Ángel Silvestre, Laya Martí, Javier Cámara, Carlos Areces, Raúl Arévalo, José María Yazpik, Guillermo Toledo, José Luis Torrijo, Lola Dueñas, Cecilia Roth, Blanca Suárez When a passenger jet headed for Mexico--which you are free to take or leave as a metaphor for Spain today--develops dangerous mechanical problems, all hell breaks loose in business class. Here we meet an amazing assortment of Almodóvarian characters, including a psychic, a chic dominatrix, a crooked businessman and a soap star. Tending to their peculiar, increasingly frantic needs are a trio of high camp stewards who react to the crisis in ways only the mischievous director could dream up--like lacing their passengers drinks with mescaline. Fasten your seat belts as this bawdy, pointed farce takes us up, up and away. Opens on Friday june 28th in New York & Los Angeles…!!! SEATTLE SEATTLE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL For more information go to http://www.siff.net/festival-2013/films-a-to-z?country=Spain Yesterday Never ends Sat, June 1 – 5:30 PM at SIFF Cinema Uptown, 511 Queen Anne Avenue N Dir. Isabel Coixet - Spain|2013|108 min. -

Introduction

Introduction 1 Iciar Bollaín (left) rehearsing Mataharis Iciar Bollaín (Madrid, 1967), actress, scriptwriter, director and producer, is one of the most striking figures currently working in the Spanish cinema, and the first Spanish woman filmmaker to make the Oscars shortlist (2010). She has performed in key films directed by, among others, Víctor Erice, José Luis Borau, Felipe Vega and Ken Loach. Starting out as assistant director and coscriptwriter, she has Santaolalla_Bollain.indd 1 04/04/2012 15:38 2 The cinema of Iciar Bollaín gone on to make four short films and five feature films to date, all but one scripted or coscripted by her. She is also one of the founding members of Producciones La Iguana S. L., a film production company in existence since 1991. Her work raises questions about authorship, female agency and the mediation in film of social issues. It also highlights the tensions between creative and industrial priori ties in the cinema, and national and transnational allegiances, while prompting reflection on the contemporary relevance of cinéma engagé. Bollaín’s contribution to Spanish cinema has been acknowledged both by filmgoers and the industry. Te doy mis ojos (Take My Eyes, 2003) is one of a handful of Spanish films seen by over one million spectators, and was the first film made by a woman ever to receive a Best Film Goya Award (Spanish Goyaequivalent) from the Academia de las Artes y las Ciencias Cinematográficas de España (Spanish Film Academy).1 Recognition has also come through her election to the Executive Committee of the College of Directors and Scriptwriters of the SGAE (Sociedad General de Autores y Editores) in July 2007, and to the VicePresidency of the Spanish Film Academy in June 2009.2 The varied range of Bollaín’s contribution to Spanish cinema, and the extent to which she is directly involved in key roles associated with filmmaking, inevitably lead to speculation on the extent to which she may be regarded as an auteur. -

La Vida Secreta De Las Palabras, Galardonada Con El XI Premio Cinematográfico José María Forqué

EGEDA BOLETIN 42-43 8/6/06 11:44 Página 1 No 42-43. 2006 Entidad autorizada por el Ministerio de Cultura para la representación, protección y defensa de los intereses de los productores audiovisuales, y de sus derechos de propiedad intelectual. (Orden de 29-10-1990 - B.O.E., 2 de Noviembre de 1990) La vida secreta de las palabras, galardonada con el XI Premio Cinematográfico José María Forqué Una historia de soledad e incomunicación, La vida secreta de las palabras, producida por El Deseo y Mediapro y dirigida por Isabel Coixet, ha sido galardonada con el Premio José María Forqué, que este año ha llegado a su undécima edición. En la gala, celebrada en el Teatro Real el 9 de mayo, La vida secreta de las palabras compartió homenaje con el documental El cielo gira, que se llevó el IV Premio Especial EGEDA, y con el productor Andrés Vicente Gómez, galardonado con la Medalla de Oro (Foto: Pipo Fernández) (Foto: de EGEDA por el conjunto de su carrera. La gala tuvo como maestros de ceremo- cida por Maestranza Films, ICAIC y Pyra- vertirán a los creadores españoles en los nias a Concha Velasco y Jorge Sanz, y con- mide Productions, y dirigida por Benito más protegidos de Europa. tó con la actuación musical del Grupo Sil- Zambrano; Obaba, producida por Oria ver Tones, que interpretó temas de rock Films, Pandora Film y Neue Impuls Film, y Por su parte, el presidente de EGEDA, En- and roll de los años 50 y 60. Esto supone dirigida por Montxo Armendáriz, y Prince- rique Cerezo, entregó la Medalla de Oro una novedad en el escenario del Teatro sas, producida por Reposado PC y Media- de la entidad al veterano productor An- Real, pues es la primera vez que acoge este pro, y dirigida por Fernando León de Ara- drés Vicente Gómez en reconocimiento “a género musical. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: María Camí-Vela University

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: María Camí-Vela University Address: University of North Carolina-Wilmington 601 S. College Rd. Wilmington, NC 28403-5954 Tel: (910)962-3342 E-mail: [email protected] I. EDUCATION Ph.D. in Spanish Literature Spring 1995 Romance Languages and Literatures University of Florida Dissertation: La búsqueda de la identidad en la obra de Carme Riera (The Search for Identity in Carme Rieras’s Narrative) Summer 1993 Universidad Complutense Madrid, Spain Course title: “Mujeres Creadoras” (“Women Creators”) M.A. in Spanish Fall 1989 Romance Languages and Literatures University of Florida Master’s Thesis: El feminismo en la obra periodística de Emilia Pardo Bazán (Feminism in Emilia Pardo Bazán’s Journalistic Works) B.A. in Spanish Fall 1986, Romance Languages and Literatures University of Florida Other Studies Fall 1975-Fall 1976 Universidad de Murcia, Spain II. TEACHING EXPERIENCE Professor: 2007- Associate Professor: 2003- 2007 Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures, U. of North Carolina -Wilmington. Assistant Professor: 1997-2003 Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures, U. of North Carolina -Wilmington. III.PUBLICATIONS AND ACADEMIC PRESENTATIONS A. Publications Books Mujeres detrás de la cámara: Entrevistas con cineastas españolas 1990-2004. (Women Behind the Camera: Interviews with Spanish Women Filmmakers 1990-2004.) Madrid: Madrid/Ocho y Medio, 2005. Mujeres detrás de la cámara: Entrevistas con cineastas españolas de la década de los 90. (Women Behind the Camera: Interviews with Spanish Women Filmmakers of the 90’s.) Madrid: Festival de Cine Experimental de Madrid/Ocho y Medio, 2001. La búsqueda de la identidad en la obra literaria de Carme Riera. (The Search for Identity in the Narrative Works of Carme Riera.) Madrid: Pliegos, 2000. -

“In a Land of Myth and a Time of Magic”: the Role and Adaptability of the Arthurian Tradition in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries Sarah Wente St

St. Catherine University SOPHIA Antonian Scholars Honors Program School of Humanities, Arts and Sciences 4-2013 “In a Land of Myth and a Time of Magic”: The Role and Adaptability of the Arthurian Tradition in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries Sarah Wente St. Catherine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://sophia.stkate.edu/shas_honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wente, Sarah, "“In a Land of Myth and a Time of Magic”: The Role and Adaptability of the Arthurian Tradition in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries" (2013). Antonian Scholars Honors Program. 29. https://sophia.stkate.edu/shas_honors/29 This Senior Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Humanities, Arts and Sciences at SOPHIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Antonian Scholars Honors Program by an authorized administrator of SOPHIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “In a Land of Myth and a Time of Magic” The Role and Adaptability of the Arthurian Tradition in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries By Sarah Wente A Senior Project in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Honors Program ST. CATHERINE UNIVERSITY April 2, 2013 Acknowledgements The following thesis is the result of many months of reading, writing, and thinking, and I would like to express the sincerest gratitude to all who have contributed to its completion: my project advisor, Professor Cecilia Konchar Farr – for her enduring support and advice, her steadfast belief in my intelligence, and multiple gifts of chocolate and her time; my project committee members, Professors Emily West, Brian Fogarty, and Jenny McDougal – for their intellectual prodding, valuable feedback, and support at every stage; Professor Amy Hamlin – for her assistance in citing the images used herein; and my friends, Carly Fischbeck, Rachel Armstrong, Megan Bauer, Tréza Rosado, and Lydia Fasteland – for their constant encouragement and support and for reading multiple drafts along the way. -

Voscope the Bookshop

Label européen des langues, prix d’excellence pour l’innovation dans l’enseignement et l’apprentissage des langues décerné par l’agence Erasmus + France / Education Formation Le supplément cinéma de Un film d'Isabel Coixet Dans les salles le 19 décembre 2018 4 pages en anglais pour découvrir le contexte historique et sociologique du film et une interview de la réalisatrice. VOCABLE Du X au X mois 2015 • 1 SYNOPSIS In 1959, Florence Green, a war widow, moves to Hardborough, a small Suffolk seaside town. She decides to buy the Old House, a derelict building, and convert it into a bookshop. But she has to battle provincialism to keep it open... The movie is an adaptation of the eponymous novel by Penelope Fitzgerald. war widow veuve de guerre / Suffolkcomté du sud-est de l’Angleterre / seaside (en) bord de mer / derelict délabré, à l’abandon / to convert transformer / to battle lutter contre, combattre / provincialism esprit de clocher / eponymous éponyme, du même nom / novel roman. (Septième Factory) NORTHERN IRELAND CREATING Crawfordsburn Helen’s Bay THE DIRECTOR HARDBOROUGH Isabel Coixet is a “I think The movie takes place in the Spanish director. behind the fictional seaside Suffolk town of Born in Barcelona in camera I'm Hardborough but was mostly shot 1960, she studied in Northern Ireland. Portaferry, history at Barcelona very a small town in County Down, University before comfortable served as Hardborough’s streets starting a successful and harbour. It is also in Portaferry career in advertising. in any place that the exterior of the Old House Portaferry In 1988, her first in the Bookshop was recreated, in a former art gallery. -

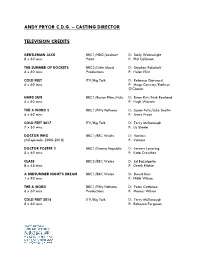

Andy Pryor C.D.G

ANDY PRYOR C.D.G. – CASTING DIRECTOR TELEVISION CREDITS GENTLEMAN JACK BBC1/HBO/Lookout D: Sally Wainwright 8 x 60 mins. Point P: Phil Collinson THE SUMMER OF ROCKETS BBC2/Little Island D: Stephen Poliakoff 6 x 60 mins. Productions P: Helen Flint COLD FEET ITV/Big Talk D: Rebecca Gatward 6 x 60 mins. P: Mags Conway/Kathryn O’Connor HARD SUN BBC1/Euston Films/Hulu D: Brian Kirk/Nick Rowland 6 x 60 mins. P: Hugh Warren THE A WORD 2 BBC1/Fifty Fathoms D: Susan Tully/Luke Snellin 6 x 60 mins. P: Jenny Frayn COLD FEET 2017 ITV/Big Talk D: Terry McDonough 7 x 60 mins. P: Lis Steele DOCTOR WHO BBC1/BBC Wales D: Various (All episodes 2005-2018) P: Various DOCTOR FOSTER 2 BBC1/Drama Republic D: Jeremy Lovering 5 x 60 mins. P: Kate Crowther CLASS BBC3/BBC Wales D: Ed Bazalgette 8 x 45 mins. P: Derek Ritchie A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM BBC1/BBC Wales D: David Kerr 1 x 90 mins P: Nikki Wilson THE A WORD BBC1/Fifty Fathoms D: Peter Cattaneo 6 x 60 mins. Productions P: Marcus Wilson P: Marcus Wilson COLD FEET 2016 ITV/Big Talk D: Terry McDonough 8 x 60 mins. P: Rebecca Ferguson [Type here] UNDERCOVER BBC1/BBC Drama D: James Hawes/Jim O’Hanlon 6 x 60 mins Productions P: Richard Stokes P: Richard Stokes CLOSE TO THE ENEMY BBC2/Little Island D: Stephen Poliakoff 6 x 60 mins. Pictures P: Helen Flint P: Helen Flint DOCTOR FOSTER BBC1/Drama Republic D: Tom Vaughan/Bruce Goodison 5 x 60 mins. -

Isabel Coixet

Written & directed by ISABEL COIXET Based on the novel by Penelope Fitzgerald “A good book is the precious life-blood of a master-spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life, and as such it must surely be a necessary commodity.” Penelope Fitzgerald - The Bookshop PITCH A town that lacks a bookshop isn’t always a town that wants one. LOGLINE England 1959. In a small East Anglian town, Florence Green decides, against polite but ruthless local opposition, to open a bookshop. SYNOPSIS Based on Penelope Fitzgerald’s novel of the same name; The Bookshop is set in 1959, Florence Green (Emily Mortimer), a free-spirited widow, puts grief behind her and risks everything to open up a bookshop – the first such shop in the sleepy seaside town of Hardborough, England. Fighting damp, cold and considerable local apathy she struggles to establish herself but soon her fortunes change for the better. By exposing the narrow-minded local townsfolk to the best literature of the day including Nabokov’s scandalising Lolita and Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, she opens their eyes thereby causing a cultural awakening in a town which has not changed for centuries. Her activities bring her a kindred spirit and ally in the figure of Mr.Brundish (Bill Nighy)who is himself sick of the town’s stale atmosphere. But this mini social revolution soon brings her fierce enemies: she invites the hostility of the town’s less prosperous shopkeepers and also crosses Mrs. Gamart (Patricia Clarkson), Hardborough’s vengeful, embittered alpha female who is herself a wannabe doyenne of the local arts scene. -

LE 18 JUILLET AU CINEMA the BOOKSHOP Un Film De Isabel Coixet

LE 18 JUILLET AU CINEMA THE BOOKSHOP Un film de Isabel Coixet Rien ne semble troubler la paix de Hardborough, aimable bourgade de l’Est de l'Angleterre. Mais quand Florence Green (Emily Mortimer), un jeune veuve, décide d’y ouvrir une librairie, elle découvre l'enfer feutré des médisances puis l’ostracisme féroce d’une partie de la population. Alors que la très influente Violet Gamart (Patricia Clarckson) monte les habitants contre son projet, Florence trouvera un soutien précieux auprès du mystérieux Mr Brundish (Bill Nighy) qui trouve que cette petite ville a bien besoin d'un souffle nouveau. Cette adaptation du livre de Penelope Fitzgerald (lauréat du Booker Prize) par Isabel Coixet a remporté 3 Goyas en Espagne : Meilleur Film, Meilleure Réalisatrion et Meilleur Scénario. Durée: 113 min. - Angleterre - 2017 Matériel presse disponible sur www.cineart.be Distribution: Presse: Cinéart Heidi Vermander 72-74, Rue de Namur T. 0475 62 10 13 1000 Bruxelles [email protected] T. 02 245 87 00 ISABEL COIXET - DIRECTOR Filmography 2017 THE BOOKSHOP 2016 SPAIN IN A DAY (documentary) 2015 NOBODY WANTS THE NIGHT 2014 LEARNING TO DRIVE 2014 ANOTHER ME 2013 YESTERDAY NEVER ENDS 2011 LISTENING TO JUDGE GARZÓN (documentary) 2010 ARAL. THE LOST SEA (short) 2009 MAP OF THE SOUNDS OF TOKYO 2008 ELEGY 2007 INVISIBLES (documentary, segment: Letters to Nora) 2003 MY LIFE WITHOUT ME 2006 PARIS JE T’AIME (segment: Bastille) 1998 TO THOSE WHO LOVE 2005 THE SECRET LIFE OF WORDS 1996 THINGS I NEVER TOLD YOU 2004 ¡HAY MOTIVO! (segment: The 1989 TOO OLD TO DIE YOUNG Unbearable Lightness of the Shopping 1984 LOOK AND SEE (short) Trolley) Isabel Coixet started filming when she was given a 8mm camera on the occasion of her First Communion.