“Don't Be a Warrior. Be a Doctor"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{TEXTBOOK} Level 3: Doctor Who: Face the Raven Kindle

LEVEL 3: DOCTOR WHO: FACE THE RAVEN Author: Nancy Taylor Number of Pages: 64 pages Published Date: 06 Sep 2018 Publisher: Pearson Education Limited Publication Country: Harlow, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781292206196 DOWNLOAD: LEVEL 3: DOCTOR WHO: FACE THE RAVEN Level 3: Doctor Who: Face The Raven PDF Book These details may be relatively unimportant to the average dancer, but it is essential that they should be correctly applied when dealing with the printed word. The book explores the attitudes, knowledge and understanding that a practitioner must adopt in order to start or develop successful Sustained Shared Thinking. In addition Ruppert gives a very useful account of his thinking about the methodology of Constellations as a means of achieving understanding and integration. If you are thinking of buying an electric vehicle or already drive one, then this book is a must for you. we remove fuel-supply line with nozzles. They reflect the actual SAT Subject Test in length, question types, and degree of difficulty. Level 3: Doctor Who: Face The Raven Writer 2016 and gives you all the essential facts about the W110 sedan and 111 and 112 two- and four-door series. Roger Mills and staff accomplished the "miracle" in the Modello and Homestead Gardens Housing Projects, applying the Three PrinciplesHealth Realization approach based on a new spiritual psychology. From Brazilian favelas to high tech Boston, from rural India to a shed inventor in England's home counties, We Do Things Differently travels the world to find the advance guard re-imagining our future. The volume assembles a rich diversity of statements, case studies and wider thematic explorations all starting with indigenous peoples as actors, not victims. -

Unsettling a Settler Family's History in Aotearoa New Zealand

genealogy Article A Tale of Two Stories: Unsettling a Settler Family’s History in Aotearoa New Zealand Richard Shaw Politics Programme, Massey University, PB 11 222 Palmerston North, New Zealand; [email protected]; Tel.: +64-27609-8603 Abstract: On the morning of the 5 November 1881, my great-grandfather stood alongside 1588 other military men, waiting to commence the invasion of Parihaka pa,¯ home to the great pacifist leaders Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kakahi¯ and their people. Having contributed to the military campaign against the pa,¯ he returned some years later as part of the agricultural campaign to complete the alienation of Taranaki iwi from their land in Aotearoa New Zealand. None of this detail appears in any of the stories I was raised with. I grew up Pakeh¯ a¯ (i.e., a descendant of people who came to Aotearoa from Europe as part of the process of colonisation) and so my stories tend to conform to orthodox settler narratives of ‘success, inevitability, and rights of belonging’. This article is an attempt to right that wrong. In it, I draw on insights from the critical family history literature to explain the nature, purposes and effects of the (non)narration of my great-grandfather’s participation in the military invasion of Parihaka in late 1881. On the basis of a more historically comprehensive and contextualised account of the acquisition of three family farms, I also explore how the control of land taken from others underpinned the creation of new settler subjectivities and created various forms of privilege that have flowed down through the generations. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Wo2 Episode 5

Wooden Overcoats 2.5 – Flip Flap Flop © T. A. Woodsmith and Wooden Overcoats Ltd. 2017 WOODEN OVERCOATS EPISODE 2.5 – FLIP FLAP FLOP By T. A. Woodsmith RECORDING SCRIPT Rudyard Funn ~ FELIX TRENCH Antigone Funn ~ BETH EYRE Eric Chapman ~ TOM CROWLEY Georgie Crusoe ~ CIARA BAXENDALE MadeLeine ~ BELINDA LANG Mayor Desmond Desmond ~ SEAN BAKER Audrey Warrington ~ FIZ MARCUS MiLes Fahrenheit ~ BEN NORRIS Thomas Johnson ~ TIMOTHY BLOCK Agatha Doyle ~ ALISON SKILBECK Dr. Edgware ~ DAVID K. BARNES Jerry ~ MAXWELL TYLER Disclaimer: All rights including but not limited to performance, production, and publication are reserved. www.woodenovercoats.com 1 Wooden Overcoats 2.5 – Flip Flap Flop © T. A. Woodsmith and Wooden Overcoats Ltd. 2017 PRE TITLES. MADELEINE: (V.O.) Rudyard Funn runs a funeraL home in the viLLage of PiffLing VaLe. He used to run it by himseLf. He doesn’t anymore. Funn FuneraLs remains entireLy unknown beyond the shores of PiffLing. But it’s due to receive important guests – and a chance to impress the world… THEME TUNE. ANNOUNCER: Wooden Overcoats, created by David K. Barnes. Season Two Episode Five: Flip Flap Flop by T. A. Woodsmith. SCENE 1. FUNN FUNERALS KITCHEN. MADELEINE: (VO.) Of course, Rudyard had no idea what the day wouLd bring when he was sat at the breakfast tabLe on Monday morning, sifting through the post. RUDYARD: (SIGH) BiLLs, biLLs and more biLLs… TOAST POPS UP. ANTIGONE! Your toast is toasted! … Why, for once, can’t somebody send me a postcard, or a coupon, or a nice threatening chain Letter? RUNNING FOOTSTEPS. ANTIGONE: (OFF) No no no no no (ENTERS) no no no no NO! 2 Wooden Overcoats 2.5 – Flip Flap Flop © T. -

This Week's TV Player Report

The TV Player Report A beta report into online TV viewing Week ending 17th January 2016 Table of contents Page 1 Introduction 2 Terminology 3 Generating online viewing data 4 Capturing on-demand viewing & live streaming 5 Aggregate viewing by TV player (On-demand & live streaming) 6 Top channels (Live streaming) 7 Top 50 on-demand programmes (All platforms) 9 Top 50 on-demand programmes (Android apps) 11 Top 50 on-demand programmes (Apple iOS apps) 13 Top 50 on-demand programmes (Website player) 15 Top 10 on-demand programmes by TV player 18 Frequently asked questions Introduction In an era of constant change, BARB continues to develop its services in response to fragmenting behaviour patterns. Since our launch in 1981, there has been proliferation of platforms, channels and catch-up services. In recent years, more people have started to watch television and video content distributed through the internet. Project Dovetail is at the heart of our development strategy. Its premise is that BARB’s services need to harness the strengths of two complementary data sources. - BARB’s panel of 5,100 homes provides representative viewing information that delivers programme reach, demographic viewing profiles and measurement of viewers per screen. - Device-based data from web servers provides granular evidence of how online TV is being watched. The TV Player Report is the first stage of Project Dovetail. It is a beta report that is based on the first outputs from BARB working with UK television broadcasters to generate data about all content delivered through the internet. This on-going development delivers a census- level dataset that details how different devices are being used to view online TV. -

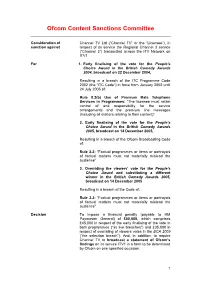

Ofcom Content Sanctions Committee

Ofcom Content Sanctions Committee Consideration of Channel TV Ltd (“Channel TV” or the “Licensee”), in sanction against respect of its service the Regional Channel 3 service (“Channel 3”) transmitted across the ITV Network on ITV1. For 1. Early finalising of the vote for the People’s Choice Award in the British Comedy Awards 2004, broadcast on 22 December 2004, Resulting in a breach of the ITC Programme Code 2002 (the “ITC Code”) in force from January 2002 until 24 July 2005 of: Rule 8.2(b) Use of Premium Rate Telephone Services in Programmes: “The licensee must retain control of and responsibility for the service arrangements and the premium line messages (including all matters relating to their content)” 2. Early finalising of the vote for the People’s Choice Award in the British Comedy Awards 2005, broadcast on 14 December 2005, Resulting in a breach of the Ofcom Broadcasting Code of: Rule 2.2: “Factual programmes or items or portrayals of factual matters must not materially mislead the audience” 3. Overriding the viewers’ vote for the People’s Choice Award and substituting a different winner in the British Comedy Awards 2005, broadcast on 14 December 2005 Resulting in a breach of the Code of: Rule 2.2: “Factual programmes or items or portrayals of factual matters must not materially mislead the audience” Decision To impose a financial penalty (payable to HM Paymaster General) of £80,000, which comprises £45,000 in respect of the early finalising of the vote in both programmes (“as live breaches”) and £35,000 in respect of overriding of viewers votes in the BCA 2005 (“the selection breach”). -

June 17 – Jan 18 How to Book the Plays

June 17 – Jan 18 How to book The plays Online Select your own seat online nationaltheatre.org.uk By phone 020 7452 3000 Mon – Sat: 9.30am – 8pm In person South Bank, London, SE1 9PX Mon – Sat: 9.30am – 11pm Other ways Friday Rush to get tickets £20 tickets are released online every Friday at 1pm Saint George and Network Pinocchio for the following week’s performances. the Dragon 4 Nov – 24 Mar 1 Dec – 7 Apr Day Tickets 4 Oct – 2 Dec £18 / £15 tickets available in person on the day of the performance. No booking fee online or in person. A £2.50 fee per transaction for phone bookings. If you choose to have your tickets sent by post, a £1 fee applies per transaction. Postage costs may vary for group and overseas bookings. Access symbols used in this brochure CAP Captioned AD Audio-Described TT Touch Tour Relaxed Performance Beginning Follies Jane Eyre 5 Oct – 14 Nov 22 Aug – 3 Jan 26 Sep – 21 Oct TRAVELEX £15 TICKETS The National Theatre Partner for Innovation Partner for Learning Sponsored by in partnership with Partner for Connectivity Outdoor Media Partner Official Airline Official Hotel Partner Oslo Common The Majority 5 – 23 Sep 30 May – 5 Aug 11 – 28 Aug Workshops Partner The National Theatre’s Supporter for new writing Pouring Partner International Hotel Partner Image Partner for Lighting and Energy Sponsor of NT Live in the UK TBC Angels in America Mosquitoes Amadeus Playing until 19 Aug 18 July – 28 Sep Playing from 11 Jan 2 3 OCTOBER Wed 4 7.30 Thu 5 7.30 Fri 6 7.30 A folk tale for an Sat 7 7.30 Saint George and Mon 9 7.30 uneasy nation. -

A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM of DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected]

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Zepponi, Noah. (2018). THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/2988 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of the Pacific Communication University of the Pacific Stockton, California 2018 3 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi APPROVED BY: Thesis Advisor: Marlin Bates, Ph.D. Committee Member: Teresa Bergman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Department Chair: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School: Thomas Naehr, Ph.D. 4 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my father, Michael Zepponi. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is here that I would like to give thanks to the people which helped me along the way to completing my thesis. First and foremost, Dr. -

Service Review

Editorial Standards Findings Appeals to the Trust and other editorial issues considered by the Editorial Standards Committee December 2012 issued February 2013 Getting the best out of the BBC for licence fee payers Editorial Standards Findings/Appeals to the Trust and other editorial issues considered Contentsby the Editorial Standards Committee Remit of the Editorial Standards Committee 2 Summaries of findings 4 Appeal Findings 6 Silent Witness, BBC One, 22 April 2012, 9pm 6 Application of Expedited Procedure at Stage 1 14 News Bulletins, BBC Radio Shropshire, 26 & 27 March 2012 19 Watson & Oliver, BBC Two, 7 March 2012, 7.30pm 26 Rejected Appeals 38 5 live Investigates: Cyber Stalking, BBC Radio 5 live and Podcast, 1 May 2011; and Cyber- stalking laws: police review urged, BBC Online, 1 May 2011 38 Olympics 2012, BBC One, 29 July 2012 2 Today, BBC Radio 4, 29 May 2012 5 Bang Goes the Theory, BBC One, 16 April 2012 9 Have I Got News For You, BBC Two, 27 May 2011and Have I Got A Bit More News For You, 2 May 2012 16 Application of expedited complaint handling procedure at Stage 1 21 Look East, BBC One 24 December 2012 issued February 2013 Editorial Standards Findings/Appeals to the Trust and other editorial issues considered by the Editorial Standards Committee Remit of the Editorial Standards Committee The Editorial Standards Committee (ESC) is responsible for assisting the Trust in securing editorial standards. It has a number of responsibilities, set out in its Terms of Reference at http://www.bbc.co.uk/bbctrust/assets/files/pdf/about/how_we_operate/committees/2011/esc_t or.pdf. -

Old Jack's Boat

OLD JACK’S BOAT / TX01: THE PEARL EARRING / POST PRODUCTION SCRIPT Post Production Script Old Jack’s Boat – TX01: The Pearl Earring By Tracey Hammett Characters appearing in this script: Jack Miss Bowline-Hitch Emily Scuttlebutt Ernie Starboard Pearl (Shelly Perriwinkle) MUSIC 1 10:00:00-0138 SCENE 1: TITLES/JACK’S INTRO/SONG IN THE TITLES OLD JACK’S BOAT TAKES A COURSE ALONG AN ANIMATED MAP. WEAVING IN AND OUT OF THE VARIOUS SITUATIONS AND CHARACTERS FROM THE STORIES. AT THE END OF THE ANIMATED JOURNEY, OLD JACK’S BOAT AT 20” RISES UP TO FORM THE ‘OLD JACKS’ BOAT LOGO. A FAST ZOOM IN TO THE BOAT’S PORTHOLE FINDS JACK EXITING HIS HOUSE ALONG WITH SALTY. 10:00:21 SCENE 2: OLD JACK’S COTTAGE JACK PULLS THE DOOR BEHIND HIM AND POINTS TO CAMERA JACK: Good day to you! JACK WINKS AND THEN STRIDES OFF DOWN THE ROAD WITH SALTY. THE MUSIC SEQUES INTO “JACK’S SONG” 10:00:28 SCENE 3: EXT VILLAGE SEES JACK WALKING THROUGH THE VILLAGE MEETING HIS VARIOUS FRIENDS. HIS FRIENDS ARE EACH ON THE WAY TO WORK. THERE IS A GENERAL AIR OF BUSY ACTIVITY AS EACH OF THE CHARACTERS GETS READY FOR 1 OLD JACK’S BOAT / TX01: THE PEARL EARRING / SHOOTING SCRIPT THEIR DAY. OLD JACK WAVES TO THEM AND THEY WAVE BACK. THE LYRICS OF THE SONG THAT JACK IS SINGING GIVE A BRIEF, FOND DESCRIPTION OF EACH OF THE CHARACTERS. AT THE END OF THIS INTRODUCTION SEQ THERE IS AN ANIMATED GRAPHIC OF A FISH THAT WIPES THROUGH FRAME. -

Werner Herzog Interview with a Legend

July/August 2019 Werner Herzog Interview with a legend David Harewood | Alex Scott | The South Bank Show CREATE MAXIMUM IMPACT WITH MUSIC A collection of epic music composed, recorded and produced specifically for film trailers and broadcast programming, from stirring emotional drama to apocalyptic action. AVAILABLE FOR LICENCE AT AUDIONETWORK.COM/DISCOVER/MAXIMUMIMPACT FIND OUT MORE: Rebecca Hodges [email protected] (0)207 566 1441 1012-RTS ADVERTS-MAX_IMPACT-V2.indd 1 25/06/2019 09:31 Journal of The Royal Television Society July/August 2019 l Volume 56/7 From the CEO We have just enjoyed We had a full house as some of televi- creative icon, Werner Herzog. His new two outstanding sion’s most successful storytellers BBC Arena film, focusing on his rela- national RTS events, shared their approaches to their craft. tionship with Bruce Chatwin, is some- the RTS Student Tele- I am very grateful to the event’s joint thing to look forward to this autumn. vision Awards and a organisers, Directors Cut Productions, Don’t miss Simon Shaps’s incisive live South Bank Show Sky Arts and Premier. review of a new book that analyses the special devoted to the I am thrilled that Alex Scott found the recent battle to own Sky, and Stewart art of screenwriting. Many thanks to time to write this edition’s Our Friend Purvis’s account of how the politics of all of you who worked hard to make column. The Women’s World Cup Brexit are challenging news broadcast- these happen. Congratulations to all really did capture and hold the pub- ers and what impartiality means in a the nominees and winners of the lic’s imagination: England’s semi-final fragmenting political landscape. -

Sociopathetic Abscess Or Yawning Chasm? the Absent Postcolonial Transition In

Sociopathetic abscess or yawning chasm? The absent postcolonial transition in Doctor Who Lindy A Orthia The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia Abstract This paper explores discourses of colonialism, cosmopolitanism and postcolonialism in the long-running television series, Doctor Who. Doctor Who has frequently explored past colonial scenarios and has depicted cosmopolitan futures as multiracial and queer- positive, constructing a teleological model of human history. Yet postcolonial transition stages between the overthrow of colonialism and the instatement of cosmopolitan polities have received little attention within the program. This apparent ‘yawning chasm’ — this inability to acknowledge the material realities of an inequitable postcolonial world shaped by exploitative trade practices, diasporic trauma and racist discrimination — is whitewashed by the representation of past, present and future humanity as unchangingly diverse; literally fixed in happy demographic variety. Harmonious cosmopolitanism is thus presented as a non-negotiable fact of human inevitability, casting instances of racist oppression as unnatural blips. Under this construction, the postcolonial transition needs no explication, because to throw off colonialism’s chains is merely to revert to a more natural state of humanness, that is, cosmopolitanism. Only a few Doctor Who stories break with this model to deal with the ‘sociopathetic abscess’ that is real life postcolonial modernity. Key Words Doctor Who, cosmopolitanism, colonialism, postcolonialism, race, teleology, science fiction This is the submitted version of a paper that has been published with minor changes in The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 45(2): 207-225. 1 1. Introduction Zargo: In any society there is bound to be a division. The rulers and the ruled.