The Evolution of in Vitro Fertilization in the United States: a Closer Look at Media Coverage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Georgeanna Seegar Jones (1912-2005) [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9883/georgeanna-seegar-jones-1912-2005-1-59883.webp)

Georgeanna Seegar Jones (1912-2005) [1]

Published on The Embryo Project Encyclopedia (https://embryo.asu.edu) Georgeanna Seegar Jones (1912-2005) [1] By: Ruffenach, Stephen C. Keywords: Biography [2] Fertilization [3] Reproductive assistance [4] Medicine [5] Georgeanna Seegar Jones [6] was a reproductive endocrinologist who created one of America’s most successfuli nfertility [7] clinics and eventually, along with her husband Howard W. Jones, MD, performed the first in vitro [8] fertilization [9] in America, leading to the birth of Elizabeth Jordan Carr. Jones was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on 6 July 1912. Her father, Dr. John King Beck Emory Seegar [10], was a practicing physician at the time working in the field of obstetrics. Early in her childhood Jones had a broken bone that eventually became infected and caused a great deal of pain, inspiring her to go into the field of medicine. Jones’ education began at Goucher College [11] in Baltimore where she received her bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1932. After graduating, she traveled to Johns Hopkins Medical School and obtained her MD in 1936. Jones then continued research in the field of reproductive physiology at Johns Hopkins University [12] until she applied for and received a fellowship at the National Institute of Health, where she was able to continue her work until 1939. It was at this point that Jones took a position working at Johns Hopkins Medical School, serving in a number of different positions including the director of the reproductive physiology lab as well as the head gynecologist of the Gynecological Endocrine Clinic at Johns Hopkins. Jones continued working in both positions, eventually becoming a full-time professor of gynecology and obstetrics until her retirement in 1978. -

Emmy Nominated Transformers Rescue Bots Returns to Discovery Family Channel with Back-To-Back Premiere Episodes Beginning Saturday, April 23

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 7, 2016 CONTACT: Jared Albert, (347) 449-1085 [email protected] EMMY NOMINATED TRANSFORMERS RESCUE BOTS RETURNS TO DISCOVERY FAMILY CHANNEL WITH BACK-TO-BACK PREMIERE EPISODES BEGINNING SATURDAY, APRIL 23 – This Season, Celebrity Guest Stars Kristen Schaal and Alex Kingston Visit Griffin Rock and TRANSFORMERS RESCUE BOTS Celebrates its 100th Episode Milestone – (New York) – Power up, energize and roll to the rescue as the fourth season of TRANSFORMERS RESCUE BOTS premieres on Discovery Family Channel with back-to-back episodes on Saturday, April 23 at 8 AM ET/7 AM CT and 8:30 AM ET/7:30 AM CT. Additionally, the animated series will introduce new characters – the first-ever female Rescue Bot “Quickshadow” voiced by Alex Kingston (“ER”) and “Chickadee” voiced by Kristen Schaal (“Bob’s Burgers”). TRANSFORMERS RESCUE BOTS will also celebrate its 100th episode milestone this season. In the season four back-to-back premiere episodes “New Normal” and “Bridge Building,” the invasion of an evil alien race forces the Rescue Bots to reveal their true extraterrestrial identities to the citizens of Griffin Rock. But before the townspeople vote on whether to let the robots in disguise stay in their town, the Autobots are transported to the Sahara Desert and must band together with their human counterparts to get home safely. Throughout the action-packed season, the Bots work tirelessly on a new project, construction of the Mainland Training Center and continue to test the powerful “Groundbridge” portal that allows them to transport between their firehouse headquarters and training center. TRANSFORMERS RESCUE BOTS follows the adventures of four young Transformers and their human counterparts – a family of emergency responders with 12-year-old Cody Burns at the center. -

Genealogical Sketch Of

Genealogy and Historical Notes of Spamer and Smith Families of Maryland Appendix 2. SSeelleecctteedd CCoollllaatteerraall GGeenneeaallooggiieess ffoorr SSttrroonnggllyy CCrroossss--ccoonnnneecctteedd aanndd HHiissttoorriiccaall FFaammiillyy GGrroouuppss WWiitthhiinn tthhee EExxtteennddeedd SSmmiitthh FFaammiillyy Bayard Bache Cadwalader Carroll Chew Coursey Dallas Darnall Emory Foulke Franklin Hodge Hollyday Lloyd McCall Patrick Powel Tilghman Wright NEW EDITION Containing Additions & Corrections to June 2011 and with Illustrations Earle E. Spamer 2008 / 2011 Selected Strongly Cross-connected Collateral Genealogies of the Smith Family Note The “New Edition” includes hyperlinks embedded in boxes throughout the main genealogy. They will, when clicked in the computer’s web-browser environment, automatically redirect the user to the pertinent additions, emendations and corrections that are compiled in the separate “Additions and Corrections” section. Boxed alerts look like this: Also see Additions & Corrections [In the event that the PDF hyperlink has become inoperative or misdirects, refer to the appropriate page number as listed in the Additions and Corrections section.] The “Additions and Corrections” document is appended to the end of the main text herein and is separately paginated using Roman numerals. With a web browser on the user’s computer the hyperlinks are “live”; the user may switch back and forth between the main text and pertinent additions, corrections, or emendations. Each part of the genealogy (Parts I and II, and Appendices 1 and 2) has its own “Additions and Corrections” section. The main text of the New Edition is exactly identical to the original edition of 2008; content and pagination are not changed. The difference is the presence of the boxed “Additions and Corrections” alerts, which are superimposed on the page and do not affect text layout or pagination. -

STAR ALEX KINGSTON COMING to MOTOR CITY COMIC CON Special Appearance Friday, May 15Th Through Sunday, May 17Th, 2020

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE “ER” AND “DOCTOR WHO” STAR ALEX KINGSTON COMING TO MOTOR CITY COMIC CON Special appearance Friday, May 15th through Sunday, May 17th, 2020 NOVI, MI. (January 21, 2020) – Motor City Comic Con, Michigan’s largest and longest running comic book and pop culture convention since 1989 is thrilled to announce Alex Kingston will be attending this year’s con. Kingston will attend on May 15th, 16th and 17th, and will host a panel Q&A, be available for autographs ($50.00) and photo ops ($60.00). To purchase tickets and for more information about autographs and photo ops, please go to – https://www.motorcitycomiccon.com/tickets/ Known for roles in some of the most popular television series in both the US and the UK, Alex Kingston began her career with a recurring role on the BBC teen drama Grange Hill. After appearing in such films as The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover and A Pin for the Butterfly, Kingston began appearing on the long-running medical drama ER in September of 1997. She first appeared in the premiere episode of the fourth season, the award-winning live episode "Ambush" where she portrayed British surgeon, Elizabeth Corday. Her character proved to be incredibly popular, appearing on the series for just over seven seasons until leaving in October 2004. Kingston did return to the role in spring 2009 during ER’s 15th and final season for two episodes. Kingston continued to entertain US audiences in November 2005, when she guest-starred in the long-running mystery drama Without a Trace. -

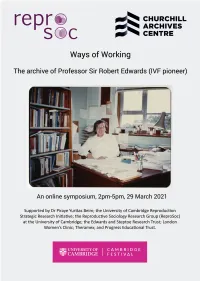

Full Programme

Ways of Working online symposium programme 2.00pm-2.05pm Welcome from Allen Packwood, Director of Churchill Archives Centre. 2.05pm-2.35pm Madelin Evans (Edwards Papers Archivist, Churchill Archives Centre) and Professor Nick Hopwood (Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge) in conversation about using the archive of Robert Edwards for research. 2.35pm-3.05pm Professor Sarah Franklin (Reproductive Sociology Research Group, University of Cambridge) and Gina Glover (Artist, creator of Art in ART: Symbolic Reproduction exhibition) on working with images of reproduction in the Edwards archive. 3.05pm-3.15pm Break, with the chance to view a film of Art in ART: Symbolic Reproduction exhibition by Gina Glover 3.15pm-3.45pm Dr Kay Elder (Senior Research Scientist, Bourn Hall Clinic) and Dr Staffan Müller-Wille (University Lecturer, Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge) on using clinical research notebooks, and scientific notebooks and manuscripts, for historical research. 3.45pm-4.15pm Professor Sir Richard Gardner (Emeritus Royal Society Research Professor in the University of Oxford) and Professor Roger Gosden (lately Professor at Cornell University, now Visiting Scholar at William & Mary and official biographer of Robert Edwards) on Robert Edwards’ style of working in the laboratory. 4.15pm-4.30pm Dr Jenny Joy (daughter of Robert Edwards, key in gathering together his archive) will talk about her experience of how her father worked. 4.30pm-5pm Concluding remarks, questions and discussion The Papers of Professor Sir Robert Edwards, at Churchill Archives Centre The archive comprises 141 boxes of personal and scientific papers including correspondence, research and laboratory notebooks, draft publications and journal articles, newspaper clippings, photographs, videos and film. -

Torchwood Doctor Who: Wicked Sisters Big Finish

ISSUE: 140 • OCTOBER 2020 WWW.BIGFINISH.COM THE TENTH DOCTOR AND RIVER SONG TOGETHER AGAIN, BUT IN WHAT ORDER? PLUS: BLAKE’S 7 | TORCHWOOD DOCTOR WHO: WICKED SISTERS BIG FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULLCAST AUDIO WE LOVE STORIES! DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND OR ABOUT BIG FINISH DOWNLOAD Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, WWW.BIGFINISH.COM Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, The @BIGFINISH Avengers, The Prisoner, The THEBIGFINISH Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain Scarlet, Space: BIGFINISHPROD 1999 and Survivors, as well BIG-FINISH as classics such as HG Wells, BIGFINISHPROD Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the SUBSCRIPTIONS Opera and Dorian Gray. If you subscribe to our Doctor We also produce original BIG FINISH APP Who The Monthly Adventures creations such as Graceless, The majority of Big Finish range, you get free audiobooks, Charlotte Pollard and The releases can be accessed on- PDFs of scripts, extra behind- Adventures of Bernice the-go via the Big Finish App, the-scenes material, a bonus Summereld, plus the Big available for both Apple and release, downloadable audio Finish Originals range featuring Android devices. readings of new short stories seven great new series: ATA and discounts. Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence Secure online ordering and Investigate, Blind Terror, details of all our products can Transference and The Human be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF Frontier. BIG FINISH WELL, THIS is rather exciting, isn’t it, more fantastic THE DIARY OF adventures with the Tenth Doctor and River Song! For many years script editor Matt Fitton and I have both dreamed of RIVER SONG hearing stories like this. -

2009 TV Land Awards' on Sunday, April 19Th

Legendary Medical Drama 'ER' to Receive the Icon Award at the '2009 TV Land Awards' on Sunday, April 19th Cast Members Alex Kingston, Anthony Edwards, Linda Cardellini, Ellen Crawford, Laura Innes, Kellie Martin, Mekhi Phifer, Parminder Nagra, Shane West and Yvette Freeman Among the Stars to Accept Award LOS ANGELES, April 8 -- Medical drama "ER" has been added as an honoree at the "2009 TV Land Awards," it was announced today. The two-hour show, hosted by Neil Patrick Harris ("How I Met Your Mother," Harold and Kumar Go To White Castle and Assassins), will tape on Sunday, April 19th at the Gibson Amphitheatre in Universal City and will air on TV Land during a special presentation of TV Land PRIME on Sunday, April 26th at 8PM ET/PT. "ER," one of television's longest running dramas, will be presented with the Icon Award for the way that it changed television with its fast-paced steadi-cam shots as well as for its amazing and gritty storylines. The Icon Award is presented to a television program with immeasurable fame and longevity. The show transcends generations and is recognized by peers and fans around the world. As one poignant quiet moment flowed to a heart-stopping rescue and back, "ER" continued to thrill its audiences through the finale on April 2, which bowed with a record number 16 million viewers. Cast members Alex Kingston, Anthony Edwards, Linda Cardellini, Ellen Crawford, Laura Innes, Kellie Martin, Mekhi Phifer, Parminder Nagra, Shane West and Yvette Freeman will all be in attendance to accept the award. -

SPECTACULAR DOCTOR WHO HD CINEMA EVENT BBC Worldwide Australasia Partners with Event Cinemas for Global Exclusive

FOR ONE NIGHT ONLY: SPECTACULAR DOCTOR WHO HD CINEMA EVENT BBC Worldwide Australasia partners with Event Cinemas for global exclusive 26 February 2013: For the first time in New Zealand, Doctor Who fans will be able to see two high definition episodes of Doctor Who on the big screen, in a special cinema event as part of the celebrations for the Doctor Who 50th anniversary year. For one night only on Thursday 14 March at 7pm, fans can experience ‘The Impossible Astronaut’ and ‘Day of the Moon’ from Series 6 in HD, a two-part story which introduced the newest monster created by series executive producer and showrunner Steven Moffat – the Silence. Screening in cinemas across New Zealand and Australia, this will be a world-first multiple cinema screening for Doctor Who. Taking place at select Event Cinemas across the country, there will be a ‘best dressed’ prize at each cinema for the Doctor Who fan with the most impressive costume, from Time Lords to Monsters. More details can be found on participating cinema websites. Written by Steven Moffat and directed by Toby Haynes, the 90-minute screening stars Matt Smith (Eleventh Doctor), Karen Gillan (Amy Pond), Arthur Darvill (Rory Williams), Alex Kingston (River Song) and Mark Sheppard (Canton Everett Delaware III). In ‘The Impossible Astronaut’, the Doctor, Amy and Rory receive a secret summons that leads them to the Oval Office in 1969. Enlisting the help of a former FBI agent and the irrepressible River Song, the Doctor promises to assist the President in saving a terrified little girl from a mysterious Space Man. -

Pag. 4 • DOCTOR WOW • PSYCHIC PAPER

P U L L T O O P E N È più grande all’interno! THE MAGAZINE • DOCTOR WEAR • DOCTOR WOW Consigli e ispirazioni per Gossip Cosmico Whovians vacanzieri in questa e altre - pag. 4 galassie - pag. 14 • DOCTOR IF • PSYCHIC PAPER Una rubrica dedicata La nostra rubrica alle fanfiction del della posta mondo Whovian - pag. 23 - pag. 6 numero 14 luglio 2021 4 Doctor Wear! Consigli e ispirazioni per Whovians vacanzieri 6 Doctor if 2021 Ogni mese vi regaliamo una fanfiction: una storia ambientata nell’universo di Doctor Who, in cui l’immaginazione di un fan muove e rein- venta i personaggi della nostra serie preferita! 14 Doctor wow! Gossip Cosmico in questa e altre galassie 16 Enigmistica whovian Giochi a tema Whovian: cruciverba e tanto altro! 21 The Shadow Proclamation luglio Metti da parte pesci, leoni e sagittari: prova il nostro Oroscopo Whovian, l’unico adattabile a più di 5 milioni di forme di vita differenti, liq- uide, solide o gassose! 25 Psychic Paper La nostra rubrica della posta... copertina, retro e grafica creati da: Bruno Alicata con l’aiuto dello staff editor testi: SakiJune, Tardis rubriche a cura di: Dalek Oba Seven Saki June Tardis Eleven Brig Alex Kingston (River Song) Inglese da parte di padre e tedesca da parte di madre, l’abbiamo conosciuta anche come Elizabeth Corday nella serie ER… tra l’altro Elizabeth è il suo secondo nome! Si è sposata tre volte e il suo primo marito è stato l’attore Ralph Fiennes. Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte di George Seurat VWORP VWORP! Pull to Open è più grande all’interno! Ogni -

Howard Wilber Jones Jr

Published on The Embryo Project Encyclopedia (https://embryo.asu.edu) Howard Wilber Jones Jr. [1] By: Zhang, Mark Keywords: Reproduction [2] Fertilization [3] Reproductive assistance [4] Howard Wilber Jones Jr. and his wife, Georgeanna Seegar Jones [5], developed a method of in vitro [6] fertilization [7] and helped create the first baby in the US using that method. Though the first in vitro [6] baby was born in England in 1978, Jones and his wife's contribution allowed for the birth of Elizabeth Carr on 28 December 1981. Jones, a gynecologist and an obstetrician, researched human reproduction for most of his life. Jones was born in Baltimore, Maryland on 30 December 1910. His father, Howard Wilber Jones Sr. was a doctor of internal medicine. From an early age, Jones Sr. allowed Jones Jr. to join him on house calls and hospital rounds. Jones's mother, Ethel Ruth Marling Jones, drove him to have the best possible education, despite only having a high school education herself. She forbade him to attend the city public schools, and she instead sent him to a more rural public school. After Jones Sr. died when he was thirteen years old, she transferred her son to a private school. In 1927 Jones matriculated to Amherst College in Amherst Massachusetts. After graduating with an undergraduate degree in 1931, he studied at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine [8] in Baltimore, Maryland, and received his MD degree in 1935, trained in gynecology and general surgery. In 1940 he took a chief residency in general surgery. After he completed his residency in 1940, Jones married Georgeanna Seegar, a gynecologist who had graduated from Johns Hopkins in 1936. -

ANNE DIXON Costume Designer

(10/17/18) ANNE DIXON Costume Designer www.anne-dixon.com FILM & TELEVISION DIRECTOR COMPANIES CAST “THE SONG OF NAMES” François Girard Serendipity Point Films Catherine McCormack Lyla Films Clive Owen Feel Films Tim Roth “SCTV REUNION SPECIAL” Martin Scorsese Insight Productions Eugene Levy Andrea Martin Martin Short “IN THE DARK” Michael Showalter CBS Television Studios Perry Mattfeld (Pilot) Red Hour Films Brooke Marham “OUR HOUSE” Anthony Scott Burns Prospero Pictures Nicola Pelt Thomas Mann “ANNE WITH AN E” Niki Caro Netflix Amybeth McNulty (Season 1) Various CBC Geraldine James Nomination: Canadian Screen Award for Best Costume Design “SHOOT THE MESSENGER” Sudz Sutherland CBC Elyse Levesque (TV Mini-Series) Various Hungry Eyes Lyriq Bent Alex Kingston “TOTAL FRAT MOVIE” Warren P. Sonoda Emerge Entertainment Nick Bateman Tom Green “LAVENDER” Ed Gass-Donnelly South Creek Pictures Abbie Cornish Dermot Mulroney Justin Long “BORN TO BE BLUE” Robert Budreau New Real Films Ethan Hawke Carmen Ejogo “WORKING THE ENGELS” Jason Priestley Shaw Media Andrea Martin (TV Series) Various Halfire Entertainment Eugene Levy Martin Short “WHAT WE HAVE” Maxime Desmons Filmshow Roberta Maxwell Maxime Desmons “THE RIGHT KIND OF WRONG” Jermiah Chechik Serendipity Point Films Ryan Kwanten Nomadic Pictures Will Sasso Catherine O’Hara “LOST GIRL” John Fawcett Syfy Anna Silk (TV Series: Seasons 1 & 2) Various Prodigy Pictures Ksenia Solo “XIII” Duane Clark Europacorp Television Stewart Townsend (TV Series: Season 1) Various Prodigy Pictures Aisha Tyler Stephen -

Lorna Jowett Is a Reader in Television Studies at the University Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NECTAR 1 The Girls Who Waited? Female Companions and Gender in Doctor Who Lorna Jowett Abstract: Science fiction has the potential to offer something new in terms of gender representation. This doesn’t mean it always delivers on this potential. Amid the hype surrounding the 50th anniversary of Doctor Who, the longest running science fiction series on television, a slightly critical edge is discernable in the media coverage concerning the casting of the twelfth Doctor and issues of representation in the series. This paper examines Doctor Who in the broader context of TV drama and changes to the TV industry, analysing the series’ gender representation, especially in the 2005 reboot, and focusing largely on the female ‘companions’. Keywords: gender representation, television, feminism, BBC. When I put together an earlier version of this paper two years ago, I discovered a surprising gap in the academic study of Doctor Who around gender. Gender in science fiction has often been studied, after all, and Star Trek, another science fiction television series starting in the 1960s (original run 1966-69) and continued via spin-offs and reboots, has long been analysed in terms of gender. So why not Doctor Who? Admittedly, Doctor Who’s creators have no clear philosophy about trying to represent a more equal society, as with the utopian Trek. The lack of scholarship on gender in Doctor Who may also be part of a lack of scholarship generally on the series—academic study of it is just gaining momentum, and only started to accumulate seriously in the last five years.