Profits and Margins Along Uganda's Charcoal Value Chain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Were Legally Registered and the Ones That Had Identified, 194 Were Not in the Register Were Found Operational by the Census Team

A SACCO Annual General Meeting in Lango, Northern Uganda Chapter Five SACCOs and MFIs 125 5.1 Failing SACCOs: Who Cares?1 Visiting a member of MAMIDECOT, a successfully managed SACCO in Masaka. Section 1 Evidence of Failure Why should anybody care about failing, – thus SACCOs seldom live their “full missing or untraceable SACCOs? Are not lives”. They therefore do not serve their institutions, like biological organisms, full purpose before dying. supposed to be subject to the immutable ii) In the remote rural areas, SACCOs are law of entropy? Are they not supposed to be often the only providers of financial born, grow, decline and die? And, given this services for most people. When the pattern, should the failing of SACCOs be an SACCOs fail, this leaves people with issue? little or no alternative services. There are three principal reasons why we iii) SACCO collapses leave people poorer should all be concerned about the failure rate and more desperate as they lose their of SACCOs in Uganda: meager savings i) Whereas in countries like Kenya the iv) Losing their money in failing SACCOs life of a SACCO spans over decades, makes poor people more cynical of the failure rate in Uganda suggests that using financial institutions. Such a most SACCOs fail after only a few years 1 Author: Andrew Obara, FRIENDS Consult 126 polluting effect entrenches financial iii. While the census team was remarkably exclusion as more low-income / poor thorough, there may have been some people get discouraged from accessing institutions which exist but were simply financial institutions’ services. -

DISTRICT BASELINE: Nakasongola, Nakaseke and Nebbi in Uganda

EASE – CA PROJECT PARTNERS EAST AFRICAN CIVIL SOCIETY FOR SUSTAINABLE ENERGY & CLIMATE ACTION (EASE – CA) PROJECT DISTRICT BASELINE: Nakasongola, Nakaseke and Nebbi in Uganda SEPTEMBER 2019 Prepared by: Joint Energy and Environment Projects (JEEP) P. O. Box 4264 Kampala, (Uganda). Supported by Tel: +256 414 578316 / 0772468662 Email: [email protected] JEEP EASE CA PROJECT 1 Website: www.jeepfolkecenter.org East African Civil Society for Sustainable Energy and Climate Action (EASE-CA) Project ALEF Table of Contents ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Background of JEEP ............................................................................................................ 8 1.2 Energy situation in Uganda .................................................................................................. 8 1.3 Objectives of the baseline study ......................................................................................... 11 1.4 Report Structure ................................................................................................................ -

18 Magado Ronald Article

GEROLD RAHMANN, VICTOR OLOWE, TIMOTHY OLABIYI, KHALID AZIM, OLUGBENGA ADEOLUWA (Eds.) (2018) Scientific Track Proceedings of the 4TH African Organic Conference. “Ecological and Organic Agriculture Strategies for Viable Continental and National Development in the Context of the African Union's Agenda 2063”. November 5-8, 2018. Saly Portudal, Senegal Impact of Climate Change on Cassava Farming a Case study of Wabinyonyi Sub county Nakasongola District Magado Ronald and Abstract Ssekyewa Charles Cassava is a potential crop to improve the livelihood of people but findings from Nakasongola District this research through conducting interviews from respondents show that 97.8% Farmers Association, responded that climate change contributed to the decline in yield. There is increased P.O Box 1, Nakasongola incidences of pest and diseases that cause rotting of the tubers that are the economic District, Uganda part used by the people. The study recommends that the Government of Uganda should strengthen climate change issues through line ministries such as Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industries and Fisheries, Ministry of Lands, Housing and Corresponding author: Urban development; Ministry of Water and Environment in terms of policies to [email protected] support the development of smallholder farmers during this era of climate change. Nakasongola District Local Government and its development partners should strengthen agricultural service delivery in all areas particularly climate Keywords: change smart agriculture and much attention should be put on cassava value Climate change, chain from production, value addition and marketing as a high value crop for mitigation mechanism, both food security and income generation. mixed cropping system, cassava, food security Introduction Cassava is widely grown and has the potential to alleviate poverty in Uganda. -

Population, Distribution and Conservation Status of Sitatunga (Tragelaphus Spekei) (Sclater) in Selected Wetlands in Uganda

POPULATION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF SITATUNGA (TRAGELAPHUS SPEKEI) (SCLATER) IN SELECTED WETLANDS IN UGANDA Biological -Life history Biological -Ecologicl… Protection -Regulation of… 5 Biological -Dispersal Protection -Effectiveness… 4 Biological -Human tolerance Protection -proportion… 3 Status -National Distribtuion Incentive - habitat… 2 Status -National Abundance Incentive - species… 1 Status -National… Incentive - Effect of harvest 0 Status -National… Monitoring - confidence in… Status -National Major… Monitoring - methods used… Harvest Management -… Control -Confidence in… Harvest Management -… Control - Open access… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -Aim… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Tragelaphus spekii (sitatunga) NonSubmitted Detrimental to Findings (NDF) Research and Monitoring Unit Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) Plot 7 Kira Road Kamwokya, P.O. Box 3530 Kampala Uganda Email/Web - [email protected]/ www.ugandawildlife.org Prepared By Dr. Edward Andama (PhD) Lead consultant Busitema University, P. O. Box 236, Tororo Uganda Telephone: 0772464279 or 0704281806 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Final Report i January 2019 Contents ACRONYMS, ABBREVIATIONS, AND GLOSSARY .......................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... viii 1.1Background ........................................................................................................................... -

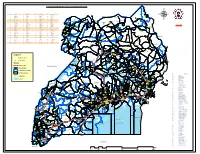

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Nakasongola-District-Local

OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF NAKASONGOLA DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2018 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL UGANDA TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS ........................................................................................................... 3 Opinion .................................................................................................................................... 4 Key Audit Matters ................................................................................................................ 4 1.0 Performance of Youth Livelihood Programme ......................................................... 5 1.1 Underfunding of the Programme ............................................................................... 5 1.2 Non-compliance with the Repayment Schedule ...................................................... 6 1.3 Transfer of Recovered Funds to the Recovery Account in BOU. ........................... 6 1.4 Inspection of Performance of Youth Projects .......................................................... 6 2.0 Implementation of the Uganda Road Funds ............................................................ 7 2.1 Budget Performance..................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Status of Implementation ............................................................................................ 8 2.2.1 Routine Manual Maintenance -

National Guidelines: Managing Healthcare Waste Generated from Safe Male Circumcision Procedures | I

AUGUST 2013 This publication was made possible through the support of the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the U.S. Agency for International Development under contract number GHH-I-00-07-00059-00, AIDS Support and Technical Assistance Resources (AIDSTAR-One) Project, Sector I, Task Order 1. Uganda National Guidelines: Managing Healthcare Waste Generated from Safe Male Circumcision Procedures | i Acronyms ACP AIDS Control Programme HCW health care waste HCWM health care waste management IP implementing partner MoH Ministry of Health NDA National Drug Authority NEMA National Environmental Management Authority PEPFAR U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief PHC primary health center PMTCT prevention of mother-to-child transmission POP persistent organic pollutants SMC safe male circumcision STI sexually transmitted infections UAC Uganda AIDS Commission UNBOS Uganda National Bureau of Standards USG U.S. Government WHO World Health Organization ii | Uganda National Guidelines: Managing Healthcare Waste Generated from Safe Male Circumcision Procedures Table of Contents Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................... ii Preface ............................................................................................................................................................. v 1.0 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................... -

Uganda Wildlife Assessment PDFX

UGANDA WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING REPORT ASSESSMENT APRIL 2018 Alessandra Rossi TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC is a leading non-governmental organisation working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. Reproduction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organisations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Published by: TRAFFIC International David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street, Cambridge CB2 3QZ, UK © TRAFFIC 2018. Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. ISBN no: UK Registered Charity No. 1076722 Suggested citation: Rossi, A. (2018). Uganda Wildlife Trafficking Assessment. TRAFFIC International, Cambridge, United Kingdom. Front cover photographs and credit: Mountain gorilla Gorilla beringei beringei © Richard Barrett / WWF-UK Tree pangolin Manis tricuspis © John E. Newby / WWF Lion Panthera leo © Shutterstock / Mogens Trolle / WWF-Sweden Leopard Panthera pardus © WWF-US / Jeff Muller Grey Crowned-Crane Balearica regulorum © Martin Harvey / WWF Johnston's three-horned chameleon Trioceros johnstoni © Jgdb500 / Wikipedia Shoebill Balaeniceps rex © Christiaan van der Hoeven / WWF-Netherlands African Elephant Loxodonta africana © WWF / Carlos Drews Head of a hippopotamus Hippopotamus amphibius © Howard Buffett / WWF-US Design by: Hallie Sacks This report was made possible with support from the American people delivered through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of USAID or the U.S. -

IOM 2009 Report

A RESPONSE ANALYSIS OF HIV/AIDS PROGRAMMING ALONG TRANSPORT CORRIDORS IN UGANDA July 2009 THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA ABOUT IOM Established in 1951, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) is the leading agency on issues of migration. IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: !Assist in meeting the growing operational challenges of migration management. !Advance understanding of migration issues. !Encourage social and economic development through migration. !Uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As-of June 2009, IOM comprised 127 Member States and I8 observer states. FINANCIAL CONTRIBUTORS AND PARTNERS Financial support was provided by the Governments of United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland through the Joint UN Team on AIDS in Uganda. AUTHORS This study report was prepared by Dr Bernadette Ssebadduka, John Ssengendo, Agatha Kafuko and Godfrey Kalikabyo. CORRESPONDENCE For further information please contact: International Organization for Migration (IOM) Uganda Mission | Plot 40 Mackenzie Vale, Kololo | PO BOX 11431 Kampala Tel: +256 414 236 622, +256 312 263 210 | Email: [email protected] COPY RIGHTS All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. A RESPONSE ANALYSIS OF HIV/AIDS PROGRAMMING ALONG TRANSPORT CORRIDORS IN UGANDA International Organization for Migration (IOM) July 2009 Contents Foreword (UAC) 2 Foreword (IOM) 3 Executive Summary 4 Acknowledgments 7 Acronyms 8 Glossary 10 1. -

NAKASONGOLA D LG Q2 .Pdf

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report Vote: 544 Nakasongola District 2014/15 Quarter 2 Structure of Quarterly Performance Report Summary Quarterly Department Workplan Performance Cumulative Department Workplan Performance Location of Transfers to Lower Local Services and Capital Investments Submission checklist I hereby submit _________________________________________________________________________. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:544 Nakasongola District for FY 2014/15. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Chief Administrative Officer, Nakasongola District Date: 3/27/2015 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District)/ The Mayor (Municipality) Page 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report Vote: 544 Nakasongola District 2014/15 Quarter 2 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Cumulative Receipts Performance Approved Budget Cumulative % Receipts Budget UShs 000's Received 1. Locally Raised Revenues 542,250 441,746 81% 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 3,185,532 1,335,265 42% 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 13,897,019 6,151,240 44% 2c. Other Government Transfers 2,631,296 1,652,264 63% 3. Local Development Grant 281,575 140,635 50% 4. Donor Funding 257,571 74,874 29% Total Revenues 20,795,242 9,796,024 47% Overall Expenditure Performance Cumulative Releases and Expenditure Perfromance Approved -

Social and Engineering Aspects of an Aquacultural Development Project in the Nakasongola District of Uganda

1 Social and Engineering Aspects of an Aquacultural Development Project in the Nakasongola District of Uganda G. W. Feyereisen Biosystems and Agricultural Engineering Department 1390 Eccles Avenue University of Minnesota St. Paul, MN 55108-6005 USA email: [email protected] Abstract: Political upheaval and civil war in the 1970’s and 1980’s, coupled with AIDS deaths in the 1980’s and 1990’s, have brought hardship on the people of the east African country of Uganda, especially the children. Cornerstone Development Uganda, a charitable organization founded in 1988, has established a 700-head working dairy cattle ranch in Nakasongola District of central Uganda to provide opportunity, education, and income for local families. Another charitable entity, African Children’s Mission (ACM), operates a feeding program providing meals to 1300 children daily at primary schools on the ranch and in the neighboring community, and organizes building projects in support of the ranch. ACM needed design assistance to build a training center, waste treatment system, and aquaculture operation on a 50 ha parcel of land adjacent to the ranch. ACM requested technical assistance from Engineering Ministries International (EMI), a U.S.-based group. EMI recruited and organized a group of eleven professionals from various parts of the United States to visit the ranch in October 2001, to complete surveys and collect data for the designs. This paper will present the social and cultural aspects of the visit, and the process of data assimilation and design that has been utilized to engineer the fish ponds and a water reservoir to support a pond aquaculture operation. -

Feasibility Study for the Establishment of a Rhino Sanctuary for Black and White Rhinos at Ziwa Ranch, Buruuli, Uganda

FEASIBILITY STUDY FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A RHINO SANCTUARY FOR BLACK AND WHITE RHINOS AT ZIWA RANCH, BURUULI, UGANDA Rob Brett Coordination with National and Continental Rhino Conservation Semester 5 task 1.3-1.4 PUBLICATION CREDITS: Title: Feasibility Study for the Establishment of a Rhino Sanctuary for Black and White Rhinos at Ziwa Ranch, Buruuli, Uganda Author: Rob Brett Date: June 2002 Special Yvonne Verkaik, Wilhelm Möller, Capt Joe Roy, Mr & Mrs Bruce Hawthorn, Richard acknowledgements: Lamprey, Moses Mapesa, Arthur Mugisha, Kenya Airways (Kampala) This report is an output from a task of the SADC Regional Programme for Rhino Conservation ABOUT the SADC Regional Programme for Rhino Conservation: The Programme is funded by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Directorate General for Development Cooperation (Project AID 5064). The Programme is contracted to CESVI and implemented through a regional consortium which comprises: The Secretariat of the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) IUCN-ROSA (The World Conservation Union - Regional Office for Southern Africa) The IUCN African Rhino Specialist Group WWF-SARPO - (World Wide Fund for Nature - Southern Africa Regional Programme Office) CESVI (Cooperazione e Sviluppo) The Programme goal is to contribute to maintain viable and well distributed metapopulations of Southern African rhino taxa as flagship species for biodiversity conservation within the SADC region. The Programme objective is to implement a pragmatic regional rhino strategy within the SADC region following the acquisition of sound information on, firstly, the constraints and opportunities for rhino conservation within each range state and secondly, the constraints and opportunities for rhino metapopulation management at the regional level.