Where There Is No Banker: Financial Systems in Remote Rural Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Were Legally Registered and the Ones That Had Identified, 194 Were Not in the Register Were Found Operational by the Census Team

A SACCO Annual General Meeting in Lango, Northern Uganda Chapter Five SACCOs and MFIs 125 5.1 Failing SACCOs: Who Cares?1 Visiting a member of MAMIDECOT, a successfully managed SACCO in Masaka. Section 1 Evidence of Failure Why should anybody care about failing, – thus SACCOs seldom live their “full missing or untraceable SACCOs? Are not lives”. They therefore do not serve their institutions, like biological organisms, full purpose before dying. supposed to be subject to the immutable ii) In the remote rural areas, SACCOs are law of entropy? Are they not supposed to be often the only providers of financial born, grow, decline and die? And, given this services for most people. When the pattern, should the failing of SACCOs be an SACCOs fail, this leaves people with issue? little or no alternative services. There are three principal reasons why we iii) SACCO collapses leave people poorer should all be concerned about the failure rate and more desperate as they lose their of SACCOs in Uganda: meager savings i) Whereas in countries like Kenya the iv) Losing their money in failing SACCOs life of a SACCO spans over decades, makes poor people more cynical of the failure rate in Uganda suggests that using financial institutions. Such a most SACCOs fail after only a few years 1 Author: Andrew Obara, FRIENDS Consult 126 polluting effect entrenches financial iii. While the census team was remarkably exclusion as more low-income / poor thorough, there may have been some people get discouraged from accessing institutions which exist but were simply financial institutions’ services. -

DISTRICT BASELINE: Nakasongola, Nakaseke and Nebbi in Uganda

EASE – CA PROJECT PARTNERS EAST AFRICAN CIVIL SOCIETY FOR SUSTAINABLE ENERGY & CLIMATE ACTION (EASE – CA) PROJECT DISTRICT BASELINE: Nakasongola, Nakaseke and Nebbi in Uganda SEPTEMBER 2019 Prepared by: Joint Energy and Environment Projects (JEEP) P. O. Box 4264 Kampala, (Uganda). Supported by Tel: +256 414 578316 / 0772468662 Email: [email protected] JEEP EASE CA PROJECT 1 Website: www.jeepfolkecenter.org East African Civil Society for Sustainable Energy and Climate Action (EASE-CA) Project ALEF Table of Contents ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Background of JEEP ............................................................................................................ 8 1.2 Energy situation in Uganda .................................................................................................. 8 1.3 Objectives of the baseline study ......................................................................................... 11 1.4 Report Structure ................................................................................................................ -

18 Magado Ronald Article

GEROLD RAHMANN, VICTOR OLOWE, TIMOTHY OLABIYI, KHALID AZIM, OLUGBENGA ADEOLUWA (Eds.) (2018) Scientific Track Proceedings of the 4TH African Organic Conference. “Ecological and Organic Agriculture Strategies for Viable Continental and National Development in the Context of the African Union's Agenda 2063”. November 5-8, 2018. Saly Portudal, Senegal Impact of Climate Change on Cassava Farming a Case study of Wabinyonyi Sub county Nakasongola District Magado Ronald and Abstract Ssekyewa Charles Cassava is a potential crop to improve the livelihood of people but findings from Nakasongola District this research through conducting interviews from respondents show that 97.8% Farmers Association, responded that climate change contributed to the decline in yield. There is increased P.O Box 1, Nakasongola incidences of pest and diseases that cause rotting of the tubers that are the economic District, Uganda part used by the people. The study recommends that the Government of Uganda should strengthen climate change issues through line ministries such as Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industries and Fisheries, Ministry of Lands, Housing and Corresponding author: Urban development; Ministry of Water and Environment in terms of policies to [email protected] support the development of smallholder farmers during this era of climate change. Nakasongola District Local Government and its development partners should strengthen agricultural service delivery in all areas particularly climate Keywords: change smart agriculture and much attention should be put on cassava value Climate change, chain from production, value addition and marketing as a high value crop for mitigation mechanism, both food security and income generation. mixed cropping system, cassava, food security Introduction Cassava is widely grown and has the potential to alleviate poverty in Uganda. -

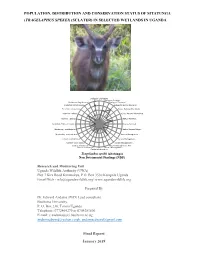

Population, Distribution and Conservation Status of Sitatunga (Tragelaphus Spekei) (Sclater) in Selected Wetlands in Uganda

POPULATION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF SITATUNGA (TRAGELAPHUS SPEKEI) (SCLATER) IN SELECTED WETLANDS IN UGANDA Biological -Life history Biological -Ecologicl… Protection -Regulation of… 5 Biological -Dispersal Protection -Effectiveness… 4 Biological -Human tolerance Protection -proportion… 3 Status -National Distribtuion Incentive - habitat… 2 Status -National Abundance Incentive - species… 1 Status -National… Incentive - Effect of harvest 0 Status -National… Monitoring - confidence in… Status -National Major… Monitoring - methods used… Harvest Management -… Control -Confidence in… Harvest Management -… Control - Open access… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -Aim… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Tragelaphus spekii (sitatunga) NonSubmitted Detrimental to Findings (NDF) Research and Monitoring Unit Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) Plot 7 Kira Road Kamwokya, P.O. Box 3530 Kampala Uganda Email/Web - [email protected]/ www.ugandawildlife.org Prepared By Dr. Edward Andama (PhD) Lead consultant Busitema University, P. O. Box 236, Tororo Uganda Telephone: 0772464279 or 0704281806 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Final Report i January 2019 Contents ACRONYMS, ABBREVIATIONS, AND GLOSSARY .......................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... viii 1.1Background ........................................................................................................................... -

Departm~N • for The

Annual Report of the Game Department for the year ended 31st December, 1935 Item Type monograph Publisher Game Department, Uganda Protectorate Download date 23/09/2021 21:05:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/35596 .. UqANDA PROTECTO ATE. I ANNUAL REPO T o THE • GAME DEPARTM~N • FOR THE . Year ended 31st December, 1935. I· ~nhli£heb hll ®ommanb of ll.li£ Ot.n:ellcncrr the Q301mnor. ENTEBBE: PRINTED BY THE GOVERNMENT PRINTER,. UGANDA• 1936 { .-r ~... .. , LIST OF CONTENTS. SECTION I.-ADMINISTRATION. PAGK. StaJr 3 Financial-Expenditure and Revenue 3 FOR THE DJegal Ki)ling of Game and Breaches of .Bame La"'s ... 5 Game Ordinance, 1926 5 Game Reserves. ... ... ... ... ... 5 Game Trophies, 'including Table of ,,·eight. of "hcence" ivory i SECTION Il.-ELEPHANT CO~TROL. Game Warden Game Ranger8 General Remarks 8 Return of Elephant. Destroyed ... ... •.. 8 Table d Control Ivory. based on tUok weight; and Notes 9 Clerk ... .•. J Table "(11 ,"'onnd Ivory from Uncon[,rolled are:>. ' .. 9 Tabld\'ot Faun.!! Ivory from Controlled sreas; and Notes - 9 Distritt Oont~t ... 10 1. Figures for-I General No~ r-Fatalities 18 Expenditure Elephant Speared 19 Visit to lYlasindi 'Township 19 Revenue Sex R.atio ... 19 Balanc'e 0" Curio,us Injury due to Fighting 19 Elephant Swimming 19 Nalive Tales 20 The revenue was Ri!!es ' 20 t(a) Sale of (b) Sale (c) Gam SECTION IlL-NOTES ON THE FAUNA. Receipts frolIl f\., (A) M'M~I'LS- (i) Primates 21 1934 figures; and from (il) Oarnivora 22 (iii) Ungulates 25 2; The result (8) BIRDS 30 November were quite (0) REPI'ILES 34 mately Shs. -

Living Lakes Goals 2019 - 2024 Achievements 2012 - 2018

Living Lakes Goals 2019 - 2024 Achievements 2012 - 2018 We save the lakes of the world! 1 Living Lakes Goals 2019-2024 | Achievements 2012-2018 Global Nature Fund (GNF) International Foundation for Environment and Nature Fritz-Reichle-Ring 4 78315 Radolfzell, Germany Phone : +49 (0)7732 99 95-0 Editor in charge : Udo Gattenlöhner Fax : +49 (0)7732 99 95-88 Coordination : David Marchetti, Daniel Natzschka, Bettina Schmidt E-Mail : [email protected] Text : Living Lakes members, Thomas Schaefer Visit us : www.globalnature.org Graphic Design : Didem Senturk Photographs : GNF-Archive, Living Lakes members; Jose Carlo Quintos, SCPW (Page 56) Cover photo : Udo Gattenlöhner, Lake Tota-Colombia 2 Living Lakes Goals 2019-2024 | Achievements 2012-2018 AMERICAS AFRICA Living Lakes Canada; Canada ........................................12 Lake Nokoué, Benin .................................................... 38 Columbia River Wetlands; Canada .................................13 Lake Ossa, Cameroon ..................................................39 Lake Chapala; Mexico ..................................................14 Lake Victoria; Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda ........................40 Ignacio Allende Reservoir, Mexico ................................15 Bujagali Falls; Uganda .................................................41 Lake Zapotlán, Mexico .................................................16 I. Lake Kivu; Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda 42 Laguna de Fúquene; Colombia .....................................17 II. Lake Kivu; Democratic -

Water Resources of Uganda: an Assessment and Review

Journal of Water Resource and Protection, 2014, 6, 1297-1315 Published Online October 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jwarp http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jwarp.2014.614120 Water Resources of Uganda: An Assessment and Review Francis N. W. Nsubuga1,2*, Edith N. Namutebi3, Masoud Nsubuga-Ssenfuma2 1Department of Geography, Geoinformatics and Meteorology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa 2National Environmental Consult Ltd., Kampala, Uganda 3Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kampala, Uganda Email: *[email protected] Received 1 August 2014; revised 26 August 2014; accepted 18 September 2014 Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Water resources of a country constitute one of its vital assets that significantly contribute to the socio-economic development and poverty eradication. However, this resource is unevenly distri- buted in both time and space. The major source of water for these resources is direct rainfall, which is recently experiencing variability that threatens the distribution of resources and water availability in Uganda. The annual rainfall received in Uganda varies from 500 mm to 2800 mm, with an average of 1180 mm received in two main seasons. The spatial distribution of rainfall has resulted into a network of great rivers and lakes that possess big potential for development. These resources are being developed and depleted at a fast rate, a situation that requires assessment to establish present status of water resources in the country. The paper reviews the characteristics, availability, demand and importance of present day water resources in Uganda as well as describ- ing the various issues, challenges and management of water resources of the country. -

Improving Emergency Care in Uganda a Low-Cost Emergency Care Initiative Has Halved Deaths Due to Emergency Conditions in Two District Hospitals in Uganda

News Improving emergency care in Uganda A low-cost emergency care initiative has halved deaths due to emergency conditions in two district hospitals in Uganda. The intervention is being scaled up nationally. Gary Humphreys reports. Halimah Adam, a nurse at the Mubende countries have no emergency access In Uganda, road traffic crashes are regional referral hospital in Uganda, telephone number to call for an ambu- a matter of particular concern. “Uganda remembers the little boy well. “He was lance, and many countries have no am- has one of the highest incidences of brought into the hospital by his mother,” bulances to call. Hospitals lack dedicated road traffic trauma and deaths on the she says. “He was unconscious and emergency units and have few providers African continent,” says Joseph Ka- barely breathing.” trained in the recognition and manage- lanzi, Senior House Officer, Emergency The mother told Halimah that the ment of emergency conditions. Medicine, Makerere University College boy had drunk paraffin, mistaking it “Over half of deaths in low- and of Health Sciences. “We are faced with for a soft drink. Paraffin (kerosene) is middle-income countries are caused multiple road traffic crashes daily and poorly absorbed by the gastrointestinal by conditions that could be addressed have barely any dedicated emergency tract, but when aspirated, which can by effective emergency care,” says Dr re s p on s e .” happen when a child vomits, it causes Teri Reynolds, an expert in emergency, According to WHO’s Global status lung inflammation, preventing the lungs trauma and acute care at the World report on road safety 2018, road traffic from oxygenating the blood. -

Museveni Receives Go Forward Executive

4 NEW VISION, Tuesday, February 2, 2016 ELECTION 2016 68 Mbabazi security men defect to NRM By Eddie Ssejjoba were formerly working as private security guards Sixty-eight musclemen and in Iraq, Afghanistan and women, claiming to belong Somalia, while others are to independent presidential veteran soldiers. candidate Amama Mbabazi’s The Team Thorough private security detail have spokesman, Godfrey Kimera defected to the National Babi, said the group would be Resistance Movement (NRM) stationed in Kampala to boost camp. the party’s security during the Composed of nine women, days left to the polling day. the group, which claimed He said for some time, they to have participated in the had been persuading the clashes with NRM supporters men, contacting them one in Ntungamo district on by one, to leave the Mbabazi December 12 last year, team and they had studied yesterday evening showed their behaviour since they up at the Team Thorough renounced their membership NRM party offices on Luthuli of Go Forward. Avenue in Kampala, wearing Ssebyala, however, said they T-shirts with the inscriptions have not heard from their of Go Forward, Mbabazi’s leader, Christopher Aine, Leaders of Go Forward from Sebei region in eastern Uganda, who defected to NRM, being introduced to political pressure group. since the Ntungamo clashes. supporters of candidate Yoweri Museveni during a rally in Kassanda, Mubende district on Sunday. PPU photo Team Thorough is a group Ntungamo was the scene of mostly youthful NRM of ugly clashes between mobilisers. supporters of the NRM and One of the bodyguards’ Go Forward on December leaders, Peter Okello, read a 12, after which Aine’s name statement before journalists, featured prominently as one stating that they had come out of the perpetrators of the Museveni receives boldly to inform the public violence. -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

Uganda Workplace HIV/AIDS Prevention Project (WAPP)

Uganda Workplace HIV/AIDS Prevention Project (WAPP) Kyenjojo Mubende Kampala RTI International is implementing a 4-year (2003–2007) HIV prevention and impact mitigation project that seeks Masaka to stem HIV infections in Ugandan informal-sector workplaces. Funded by the U.S. Department of Labor, the program provides support for approaches that include ■ “ABC” (abstinence, being faithful, condom use) HIV prevention methods Accomplishments to date ■ Prevention of mother-to-child transmission During the past 2 years, RTI has reached nearly 530,000 ■ Reduction of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and people through project-supported programs. Informal- discrimination at the workplace sector workers reached include market vendors, boda ■ Mitigation of the impact of HIV/AIDS among informal- boda (motorcycle and bicycle) transporters, carpenters, sector workers and their families. fi shermen and fi sh processors, taxi operators, food vendors and attendants, bar and lodge attendants, shop attendants, Collaboration shoe shiners, and tea harvesters. Project-supported activities We collaborate closely with the government, national and include the following: international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and community- and faith-based organizations (CBOs and Group education on HIV/AIDS FBOs). Th e program strengthens the ability of CBOs and With its partner FBOs and CBOs, RTI has successfully FBOs to better implement HIV/AIDS activities locally. organized 850 HIV/AIDS education and awareness campaigns for informal-sector workers that include Operating in Kampala, Kyenjojo, Masaka, and Mubende/ health talks, drama, and testimonies from persons living Mityana districts, RTI’s approach is to reach a large number with HIV/AIDS, combined with dialogue sessions where of informal-sector workers with HIV prevention and participants are encouraged to ask questions and off er mitigation messages through cost-eff ective and effi cient their own perspectives on HIV prevention. -

Office of the Auditor General the Republic of Uganda

OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF MITYANA DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2018 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL UGANDA TABLE OF CONTENTS Opinion ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Basis for Opinion ...................................................................................................................... 5 Key Audit Matters .................................................................................................................... 5 1.0 Performance of Youth Livelihood Programme ......................................................... 6 1.1 Underfunding of the Programme ............................................................................... 6 1.2 Non Compliance with the Repayment Schedules .................................................... 7 1.3 Inspection of Performance of YLP Projects .............................................................. 7 1.3.1 Miggo Agricultural Produce Project ........................................................................ 7 1.3.2 Youth Vision 2040 ..................................................................................................... 8 2.0 Implementation of the Uganda Road Funds ............................................................ 8 2.1 Budget Performance .....................................................................................................