Improving Emergency Care in Uganda a Low-Cost Emergency Care Initiative Has Halved Deaths Due to Emergency Conditions in Two District Hospitals in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buikwe District Economic Profile

BUIKWE DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT P.O.BOX 3, LUGAZI District LED Profile A. Map of Buikwe District Showing LLGs N 1 B. Background 1.1 Location and Size Buikwe District lies in the Central region of Uganda, sharing borders with the District of Jinja in the East, Kayunga along river Sezibwa in the North, Mukono in the West, and Buvuma in Lake Victoria. The District Headquarters is in BUIKWE Town, situated along Kampala - Jinja road (11kms off Lugazi). Buikwe Town serves as an Administrative and commercial centre. Other urban centers include Lugazi, Njeru and Nkokonjeru Town Councils. Buikwe District has a total area of about 1209 Square Kilometres of which land area is 1209 square km. 1.2 Historical Background Buikwe District is one of the 28 districts of Uganda that were created under the local Government Act 1 of 1997. By the act of parliament, the district was inniatially one of the Counties of Mukono district but later declared an independent district in July 2009. The current Buikwe district consists of One County which is divided into three constituencies namely Buikwe North, Buikwe South and Buikwe West. It conatins 8 sub counties and 4 Town councils. 1.3 Geographical Features Topography The northern part of the district is flat but the southern region consists of sloping land with great many undulations; 75% of the land is less than 60o in slope. Most of Buikwe District lies on a high plateau (1000-1300) above sea level with some areas along Sezibwa River below 760m above sea level, Southern Buikwe is a raised plateau (1220-2440m) drained by River Sezibwa and River Musamya. -

The Least Cost Generation Plan 2016

THE LEAST COST GENERATION PLAN 2016 – 2025 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In 2013, the Authority developed a 5 year Least Cost Generation Plan (LCGP) that covered the period 2013 to 2018. An update of the LCGP has been undertaken covering a 10 year period of 2016 to 2025. The update involved review of the load forecast in light of changed parameters, commissioning dates for committed projects, costs of generation plants, transmission and distribution system investment requirements. In the update of the plan, similar to the Power Sector Investment Plan, prepared by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development, the ”Econometric Demand” forecasting method was used at distribution level to forecast Commercial, Medium Industry and Large Industry customer category demand. A bottom up approach was used for Domestic customer category using the end-user method. A Base Case, Low Case and High Case scenario were developed for sensitivity analysis. The resultant demand forecast was 6.5%, 3.6% and 12% growth rate in energy demand for the Base Case, Low Case and High Case scenarios respectively. This growth rate is lower than the projection in the 2013 LCGP of 10%, 5% and 14% for Base Case, Low Case and High Case respectively. A number of energy supply options were considered including Hydro, Peat, Solar PV, Bagasse Cogeneration, Wind and Natural Gas. The planned supply considered already existing, committed and candidate generation plants/projects with their estimated commissioning dates aligned. We note that more than 80% of the generation will come from hydro. 1 In the demand supply balance, Figure E1 shows the demand and supply balance over the planning period. -

Fighting HIV and AIDS in Uganda

Fighting HIV and AIDS in Uganda Approximately 34 million men, women, and children today suffer from an illness that was unknown just 20 years ago. That illness is HIV/AIDS. Almost 70 per cent of the global total of HIV-positive people live in sub-Saharan Africa. Whilst in Europe and North America, AIDS is often perceived to be a disease of minorities, such as gay men or injecting drug users, in Africa it is the opposite. AIDS has affected millions of households, and the principal means of transmission is heterosexual intercourse. In the last 20 years, millions of people have died, and AIDS is now the most common cause of death amongst adults in Africa. Because AIDS tends to be most prevalent amongst the working population - those between 15 and 50 years of age - it causes poverty and destitution for their families and dependents. Uganda was one of the first countries in Africa to be hit by AIDS. Originally called 'slim' because of the wasting effect it has on the body, it was the subject of fear and superstition when it first appeared in the early 1980s. In this climate, the government of William seeking help from Uganda took an unusual and brave step. At a time when HIV and AIDS Kitovu Hospital's mobile health programme in 1991. Dying of were still poorly understood, and considered by some to be a 'deviants' AIDS, he was desperate to find plague', the Minister of Health travelled to the World Health Assembly in someone who would look after 1986 and spoke publicly about the extent and nature of AIDS in Uganda. -

IGG Report 2017.Indd

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA BI-ANNUALBI-ANNUAL INSPECTORATE INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENTGOVERNMENT PERFORMANCEPERFORMANCE REPORT REPORT TOTO PARLIAMENTPARLIAMENT JANUARY - JUNE 2017 MandateMandate To promote just utilization of public resources VisionVision A responsive and accountable public sector MissionMission To promote good governance, accountability and rule of law in public offfice CCoreore ValuesValues Integrity Impartiality Professionalism Gender Equality and Equity INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT BI-ANNUAL INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT PERFORMANCE REPORT TO PARLIAMENT JANUARY – JUNE 2017 THE LEADERSHIP OF THE INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT Justice Irene Mulyagonja Kakooza Inspector General of Government Ms. Mariam Wangadya Mr. George Bamugemereire Deputy Inspector General of Deputy Inspector General of Government Government Ms. Rose N. Kafeero Secretary to the Inspectorate of Government THE INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT Jubilee Insurance Centre, Plot 14, Parliament Avenue P.O. Box 1682 Kampala, Uganda General Lines: 0414-255892/259738 z Hotlines: 0414-347387/0312-101346 Fax: 0414-344810 z Email: [email protected] z Website: www.igg.go.ug Facebook: Inspectorate of Government z Twitter: @IGGUganda YouTube: Inspectorate of Government OFFICE OF THE INSPECTOR GENERAL OF GOVERNMENT Inspector General of Government Justice Irene Mulyagonja Kakooza Tel: 0414-259723 z Email: [email protected] Deputy Inspector General of Government Deputy Inspector General of Government Mr. George Bamugemereire Ms. Mariam Wangadya Tel: 0414-259780 Tel: 0414-259709 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Department of Finance and Administration: Secretary to the Inspectorate of Government Undersecretary Finance and Administration Ms. Rose N. Kafeero Ms. Glory Anaƾun Tel: 0414-259788; Fax: 0414-257590 Tel: 0414-230398 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Information and Internal Inspection Division Public and International Relations Division Head of Division: Mr. -

Ministry of Health

UGANDA PROTECTORATE Annual Report of the MINISTRY OF HEALTH For the Year from 1st July, 1960 to 30th June, 1961 Published by Command of His Excellency the Governor CONTENTS Page I. ... ... General ... Review ... 1 Staff ... ... ... ... ... 3 ... ... Visitors ... ... ... 4 ... ... Finance ... ... ... 4 II. Vital ... ... Statistics ... ... 5 III. Public Health— A. General ... ... ... ... 7 B. Food and nutrition ... ... ... 7 C. Communicable diseases ... ... ... 8 (1) Arthropod-borne diseases ... ... 8 (2) Helminthic diseases ... ... ... 10 (3) Direct infections ... ... ... 11 D. Health education ... ... ... 16 E. ... Maternal and child welfare ... 17 F. School hygiene ... ... ... ... 18 G. Environmental hygiene ... ... ... 18 H. Health and welfare of employed persons ... 21 I. International and port hygiene ... ... 21 J. Health of prisoners ... ... ... 22 K. African local governments and municipalities 23 L. Relations with the Buganda Government ... 23 M. Statutory boards and committees ... ... 23 N. Registration of professional persons ... 24 IV. Curative Services— A. Hospitals ... ... ... ... 24 B. Rural medical and health services ... ... 31 C. Ambulances and transport ... ... 33 á UGANDA PROTECTORATE MINISTRY OF HEALTH Annual Report For the year from 1st July, 1960 to 30th June, 1961 I.—GENERAL REVIEW The last report for the Ministry of Health was for an 18-month period. This report, for the first time, coincides with the Government financial year. 2. From the financial point of view the year has again been one of considerable difficulty since, as a result of the Economy Commission Report, it was necessary to restrict the money available for recurrent expenditure to the same level as the previous year. Although an additional sum was available to cover normal increases in salaries, the general effect was that many economies had to in all be made grades of staff; some important vacancies could not be filled, and expansion was out of the question. -

E464 Volume I1;Wj9,GALIPROJECT 4 TOMANSMISSIONSYSTEM

E464 Volume i1;Wj9,GALIPROJECT 4 TOMANSMISSIONSYSTEM Public Disclosure Authorized Preparedfor: UGANDA A3 NILE its POWER Richmond;UK Public Disclosure Authorized Fw~~~~I \ If~t;o ,.-, I~~~~~~~ jt .4 ,. 't' . .~ Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by: t~ IN),I "%4fr - - tt ?/^ ^ ,s ENVIRONMENTAL 111teinlauloln.al IMPACT i-S(. Illf STATEME- , '. vi (aietlph,t:an,.daw,,, -\S_,,y '\ /., 'cf - , X £/XL March, 2001 - - ' Public Disclosure Authorized _, ,;' m.. .'ILE COPY I U Technical Resettlement Technical Resettlement Appendices and A e i ActionPlan ,Community ApenicsAcinPla Dlevelopment (A' Action Plan (RCDAP') The compilete Bujagali Project EIA consists of 7 documents Note: Thetransmission system documentation is,for the most part, the same as fhat submittedto ihe Ugandcn National EnvironmentalManagement Authority(NEMAI in December 2000. Detailsof the changes made to the documentation betwoon Dccomber 2000 and the presentsubmission aro avoiloblo from AESN P. Only the graphics that have been changed since December, 2000 hove new dates. FILE: DOChUME[NTC ,ART.CD I 3 fOOt'ypnIp, .asod 1!A/SJV L6'.'''''' '' '.' epurf Ut tUISWXS XillJupllD 2UI1SIXg Itb L6 ... NOJIDSaS1J I2EIof (INY SISAlVNV S2IAIlVNTIuaJ bV _ b6.sanl1A Puu O...tp.s.. ZA .6san1r^A pue SD)flSUIa1DJltJJ WemlrnIn S- (7)6. .. .--D)qqnd llH S bf 68 ..............................................................--- - -- io ---QAu ( laimpod u2Vl b,-£ 6L ...................................... -SWulaue lu;DwIa:43Spuel QSI-PUU'l Z btl' 6L .............................................----- * -* -SaULepunog QAfjP.4SlUTtUPad l SL. sUOItllpuo ltUiOUOZg-OioOS V£ ££.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~A2~~~~~~~~~3V s z')J -4IOfJIrN 'Et (OAIOsOa.. Isoa0 joJxxNsU uAWom osILr) 2AX)SO> IsaIo4 TO•LWN ZU£N 9s ... suotll puoD [eOT20olla E SS '' ''''''''..........''...''................................. slotNluolqur wZ S5 ' '' '' '' ' '' '' '' - - - -- -........................- puiN Z'Z'£ j7i.. .U.13 1uu7EF ................... -

I UGANDA MARTYRS UNIVERSITY MOTHER KEVIN POSTGRADUATE

UGANDA MARTYRS UNIVERSITY MOTHER KEVIN POSTGRADUATE MEDICAL SCHOOL SHORT TERM POOR OUTCOME DETERMINANTS OF PATIENTS WITH TRAUMATIC PELVIC FRACTURES: A CROSSECTIONAL STUDY AT THREE PRIVATE NOT FOR PROFIT HOSPITALS OF NSAMBYA, LUBAGA AND MENGO. PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: OSUTA HOPE METHUSELAH, MBChB (KIU) REG. NO: 2016/M181/10017 SUPERVISORS: 1- MR MUTYABA FREDERICK – MBChB(MUK), M.MED SURGERY, FCS ORTHOPAEDICS 2- SR.DR. NASSALI GORRETTI - MBChB(MUK), M.MED SURGERY, FCS A DISSERTATION TO BE SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MEDICINE IN SURGERY OF UGANDA MARTYRS UNIVERSITY © AUGUST 2018 i DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my dear wife, children and siblings for their faith in me, their unwavering love and support and to my teachers for their availability, patience, guidance, shared knowledge and moral support. ii AKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to acknowledge all the patients whose information we used in this study and the institutions in which we conducted this study, for graciously granting us access to relevant data and all the support. I also would like to express my sincere gratitude to my dissertation supervisors, Mr. Mutyaba Frederick and Sr.Dr. Nassali Gorretti whose expertise, understanding, and patience have added substantially to my masters’ experience and this dissertation in particular. Special thanks go out to Professor. Kakande Ignatius, the Late Mr. Ekwaro Lawrence, Mr. Mugisa Didace, Mr. Muballe Boysier, Mr. Ssekabira John. Mr. Kiryabwire Joel, Dr.Basimbe Francis, Dr. Magezi Moses, Sr.Dr. Nabawanuka Assumpta, Dr. Nakitto Grace, Dr. Ssenyonjo Peter, my senior and junior colleagues in this journey, the Nursing Staff, the Radiology, Laboratory and Records staff whose expertise, assistance and guidance have been invaluable through my postgraduate journey. -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

Uganda Workplace HIV/AIDS Prevention Project (WAPP)

Uganda Workplace HIV/AIDS Prevention Project (WAPP) Kyenjojo Mubende Kampala RTI International is implementing a 4-year (2003–2007) HIV prevention and impact mitigation project that seeks Masaka to stem HIV infections in Ugandan informal-sector workplaces. Funded by the U.S. Department of Labor, the program provides support for approaches that include ■ “ABC” (abstinence, being faithful, condom use) HIV prevention methods Accomplishments to date ■ Prevention of mother-to-child transmission During the past 2 years, RTI has reached nearly 530,000 ■ Reduction of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and people through project-supported programs. Informal- discrimination at the workplace sector workers reached include market vendors, boda ■ Mitigation of the impact of HIV/AIDS among informal- boda (motorcycle and bicycle) transporters, carpenters, sector workers and their families. fi shermen and fi sh processors, taxi operators, food vendors and attendants, bar and lodge attendants, shop attendants, Collaboration shoe shiners, and tea harvesters. Project-supported activities We collaborate closely with the government, national and include the following: international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and community- and faith-based organizations (CBOs and Group education on HIV/AIDS FBOs). Th e program strengthens the ability of CBOs and With its partner FBOs and CBOs, RTI has successfully FBOs to better implement HIV/AIDS activities locally. organized 850 HIV/AIDS education and awareness campaigns for informal-sector workers that include Operating in Kampala, Kyenjojo, Masaka, and Mubende/ health talks, drama, and testimonies from persons living Mityana districts, RTI’s approach is to reach a large number with HIV/AIDS, combined with dialogue sessions where of informal-sector workers with HIV prevention and participants are encouraged to ask questions and off er mitigation messages through cost-eff ective and effi cient their own perspectives on HIV prevention. -

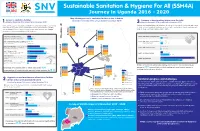

SSH4A Uganda Poster 1

Sustainable Sanitation & Hygiene For All (SSH4A) Journey in Uganda 2016 - 2020 Map showing access to sanitation facilities in the 9 districts Access to sanitation facilities (Baseline December 2016 versus Endline November 2019) Presence of hand washing station near the toilet 1. (Baseline December 2016 versus Endline November 2019) 3.(Baseline December 2016 versus Endline November 2019) Universal access to adequate sanitation is a fundamental need, human N Having and maintaining a toilet alone is not good enough. Households also need BL 1.6% right and a key part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). EL 0.0% to have a hand washing facility near their toilet and practice hand washing with The 9 SSH4A Districts were supported by SNV through the SSH4A BL 35.9% soap to improve their hygiene and health. EL 49.2% BL 11.6% program to improve sanitation and Hygiene. BL 32.8% EL 1.3% EL 32.2% BL 36.0% BL 21.1% ZOMBO EL 34.6% EL 12.7% BL 17.4% 2016 0.15% Level 5: Environmentally safe toilets 2016 7.5% EL 10.3% Level 4: HW station running tap water (a toilet where the faecal sludge does not 2019 6.8% 2019 9.8% BL 22.1% contaminate/leak into the environment) EL 43.6% PAKWACH Level 4: Improved toilets with fly management 2016 1.2% Level 3: HW station, no contamination 2016 0.42% (an improved latrine that does not allow flies to (has running water) get out of the latrine) 2019 0.3% 2019 7.04% BL 37.6% EL 3.8% BL 54.6% Level 3: Improved toilets (a toilet that has a slab BL 34.2% 2016 23.9% BL 6.6% EL 1.7% 2016 0.32 % with one hole, a door/screen -

Croc's July 1.Indd

CLASSIFIED ADVERTS NEW VISION, Monday, July 1, 2013 57 BUSINESS INFORMATION MAYUGE SUGAR INDUSTRIES LTD. SERVICE Material Testing EMERGENCY VACANCIES POLICE AND FIRE BRIGADE: Ring: 999 or 342222/3. One of the fastest developing and THE ONLY 6. BOILER ATTENDANT - 3 Posts Africa Air Rescue (AAR) 258527, MANUFACTURER OF SULPHURLESS SUGAR IN Boiler Attendant Certificate Holders with 3-5 258564, 258409. EAST AFRICA based in Uganda. The organization yrs working experience preferred (Thermo ELECTRICAL FAILURE: Ring is engaged in the manufacturing of “Nile Sugar” fluid handling) UMEME on185. and soon starting the manufacturing of Extra 7. SR. ELECTRICAL & INSTRUMENTATION ENGR. MATERIAL TESTING AND SURVEY EQUIPMENT Water: Ring National Water and Neutral Alcohol Invites applications for below - 1Post Sewerage Corporation on 256761/3, 242171, 232658. Telephone inquiry: posts; B.E.(electrical & instrumentation) or equallent Material Testing UTL-900, Celtel 112, MTN-999, 112 1. SHIFT CHEMIST FOR DISTILLATION - 3 Posts with experience of 15 years FUNERAL SERVICES Must have 3-5 years of experience in PLC/ 8. ELECTRICAL ENGR - 1 Post Aggregates impact Value Kampala Funeral Directors, SKADA system independent operation . Diploma in Electrical Engr.or equallent with Apparatus Bukoto-Ntinda Road. P.O. Box 9670, Qualification :-B.SC.Alco,Tech or Diploma in exp of 5 yrs Flakiness Gauge&Flakiness Chem Eng. 9. INSTRUMENTATION ENGR. - 1 Post Kampala. Tel: 0717 533533, 0312 Sleves 533533. 2. LABORATORY CHEMIST SHIFT - 3 Posts Diploma in Instrumentation or equallent with Los Angeles Abrasion Machine Uganda Funeral Services For Mol Analysis /Spirit Analysis /Q.C exp of 5 yrs H/Q 80A Old Kira Road, Bukoto Checking/Spent wash loss checking etc 10. -

Health Sector Semi-Annual Monitoring Report FY2020/21

HEALTH SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/21 MAY 2021 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug MOFPED #DoingMore Health Sector: Semi-Annual Budget Monitoring Report - FY 2020/21 A HEALTH SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/21 MAY 2021 MOFPED #DoingMore Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .............................................................................iv FOREWORD.........................................................................................................................vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................vii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY........................................................................................2 2.1 Scope ..................................................................................................................................2 2.2 Methodology ......................................................................................................................3 2.2.1 Sampling .........................................................................................................................3