The Posthumous Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investment Proposal (Project) Application Form of GREENFIЕLD

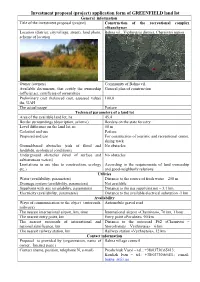

Investment proposal (project) application form of GREENFIЕLD land lot General information Title of the investment proposal (project) Construction of the recreational complex «Stanchyna» Location (district, city/village, street), land photo, Bahna vil., Vyzhnytsia district, Chernivtsi region scheme of location Owner (owners) Community of Bahna vil. Available documents, that certify the ownership General plan of construction (official act, certificate of ownership) Preliminary cost (balanced cost, assessed value) 100,0 ths. UAH The actual usage Pasture Technical parameters of a land lot Area of the available land lot, ha 45,4 Border surroundings (description, scheme) Borders on the state forestry Level difference on the land lot, m 50 m Cadastral end use Pasture Proposed end use For construction of touristic and recreational center, skiing track Ground-based obstacles (risk of flood and No obstacles landslide, ecological conditions) Underground obstacles (level of surface and No obstacles subterranean waters) Limitations in use (due to construction, ecology According to the requirements of land ownership etc.) and good-neighborly relations Utilities Water (availability, parameters) Distance to the source of fresh water – 250 m Drainage system (availability, parameters) Not available Supplying with gas (availability, parameters) Distance to the gas supplying net – 3,1 km. Electricity (availability, parameters) Distance to the available electrical substation -1 km Availability Ways of communication to the object (autoroads, Automobile gravel -

Wojciech Molendowicz

Wojciech Molendowicz Bobowa 2009 Serdecznie dziękuję za pomoc Pani Barbarze Kowalskiej, bez której wiedzy, pasji i miłości do Bobowej, ta książka nie miałaby szans powstać. Autor Partnerzy wydania: Projekt i opracowanie graczne – Tomasz Bocheński Opieka redakcyjna i korekta – Katarzyna Gajdosz Fotoedytor – Kuba Toporkiewicz Na okładce: najstarsza bobowska pocztówka z 1900 r., ze zbiorów Leszka Wojtasiewicza © Copyright by Wojciech Molendowicz, Bobowa 2009 ISBN 978-83-60822-57-9 Wydawca: Agencja Artystyczno-Reklamowa „Great Team” Rafał Kmak ul. Fiołkowa 52, 33-395 Chełmiec kontakt: 0-697-715-787 Współwydawca i Druk: Wydawnictwo i Drukarnia NOVA SANDEC ul. Lwowska 143, 33-300 Nowy Sącz tel. 018 547 45 45, e-mail: [email protected] Zdjęcia w książce: Bogdan Belcer, Krakowskie Towarzystwo Fotograczne, Grzegorz Ziemiański oraz prywatne archiwa bobowian, m.in.: Barbary Durlak, Józefy Myśliwiec, Beaty Król, Leszka Wojtasiewicza, Olgi Potoczek, Barbary Kowalskiej, Leszka Wieniawy-Długoszowskiego, Jana Wojtasa, Zoi Tokarskiej, Leokadii Hebdy, Zoi Rębisz, Antoniego Szczepanka, Katarzyny Fałdy, Antoniego Szpili, Zoi Chmury, Emilii Ślęczkowskiej. W materiałach archiwalnych składnia, ortograa i interpunkcja zostały zachowane zgodnie z oryginałem. WSTĘP choć niedawno ponownie stała się miastem, ciągle pozostaje częścią globalnej wioski. Dziś, nie wychodząc z domu, więcej wiemy o wydarzeniach na drugim Bobowa, końcu świata, niż o najbliższym sąsiedzie. Mam nadzieję, że ta książka choć tro- chę wzbogaci naszą wiedzę o tym, co nas otacza. Nie powinniśmy mieć żadnych kompleksów. Blisko 700-letnia historia Bo- bowej pełna jest wydarzeń niezwykłych, a dzień dzisiejszy pokazuje, że ludzie związani z tym miastem świetnie sobie radzą w przeróżnych profesjach w Polsce i świecie. Stosunkowo niedawno w jednej z codziennych gazet napisano takie oto zda- nie: „Bobowa – dziura zabita dechami”. -

Stamford Hill.Pdf

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Housing Studies on Volume 33, 2018. Schelling-Type Micro-Segregation in a Hassidic Enclave of Stamford-Hill Corresponding Author: Dr Shlomit Flint Ashery Email [email protected] Abstract This study examines how non-economic inter- and intra-group relationships are reflected in residential pattern, uses a mixed methods approach designed to overcome the principal weaknesses of existing data sources for understanding micro residential dynamics. Micro-macro qualitative and quantitative analysis of the infrastructure of residential dynamics offers a holistic understanding of urban spaces organised according to cultural codes. The case study, the Haredi community, is composed of sects, and residential preferences of the Haredi sect members are highly affected by the need to live among "friends" – other members of the same sect. Based on the independent residential records at the resolution of a single family and apartment that cover the period of 20 years the study examine residential dynamics in the Hassidic area of Stamford-Hill, reveal and analyse powerful Schelling-like mechanisms of residential segregation at the apartment, building and the near neighbourhood level. Taken together, these mechanisms are candidates for explaining the dynamics of residential segregation in the area during 1995-2015. Keywords Hassidic, Stamford-Hill, Segregation, Residential, London Acknowledgments This research was carried out under a Marie Curie Fellowship PIEF-GA-2012-328820 while based at Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (CASA) University College London (UCL). 1 1. Introduction The dynamics of social and ethnoreligious segregation, which form part of our urban landscape, are a central theme of housing studies. -

Vol-26-2E.Pdf

Table of Contents // June 2012 2-3 | Dr. Leah Teicher / From the Editor’s Desk. 4 | Dr. Leah Haber-Gedalia / Chairperson’s Note. 5-15 | Dr. Leah Haber-Gedalia / Jewish Galicia Geography, Demography, History and Culture. 16-27 | Pamela A.Weisberger / Galician Genealogy: Researching Your Roots with "Gesher Galicia". 28-36 | Dr. Eli Brauner / My Journey in the Footsteps of Anders’ Army. 37-50 | Immanuel (Ami) Elyasaf / Decoding Civil Registry and Mapping the Brody Community Cemetery. 51-57 | Amnon Atzmon / The Town of Yahil'nytsya - Memorial Website. 58 | Some Galician Web Pages. 59-60 | Instructions for writing articles to be published in "Sharsheret Hadorot". The Israel Genealogical Society | "Sharsheret Hadorot" | 1 | From the Editor’s Desk // Dr. Leah Teicher Dear Readers, “Er iz a Galitsianer”, my father used to say about a Galician Jew, and that said everything about a person: he had a sense of humor; he was cunning, a survivor, a reader, a fan of music, musicians and culture; a religious person, and mostly, a Yiddish speaker and a Holocaust survivor. For years, Galicia had been a part of Poland. Its scenery, woods and rivers had been our parents’ memories. A Jewish culture had developed in Galicia, the Yiddish language was created there, customs established, unique Jewish foods cooked, the figure of the “Yiddishe Mame” developed, inspiring a good deal of genealogical research; “Halakhot” and Rabbinic Laws made; an authoritative leadership established in the towns, organizing communities on their social institutions – Galicia gave birth to the “Shttetl” – the Jewish town, on all its social-historical and emotional implications. -

DLA Piper. Details of the Member Entities of DLA Piper Are Available on the Website

EUROPEAN PPP REPORT 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Report has been published with particular thanks to: The EPEC Executive and in particular, Livia Dumitrescu, Goetz von Thadden, Mathieu Nemoz and Laura Potten. Those EPEC Members and EIB staff who commented on the country reports. Each of the contributors of a ‘View from a Country’. Line Markert and Mikkel Fritsch from Horten for assistance with the report on Denmark. Andrei Aganimov from Borenius & Kemppinen for assistance with the report on Finland. Maura Capoulas Santos and Alberto Galhardo Simões from Miranda Correia Amendoeira & Associados for assistance with the report on Portugal. Gustaf Reuterskiöld and Malin Cope from DLA Nordic for assistance with the report on Sweden. Infra-News for assistance generally and in particular with the project lists. All those members of DLA Piper who assisted with the preparation of the country reports and finally, Rosemary Bointon, Editor of the Report. Production of Report and Copyright This European PPP Report 2009 ( “Report”) has been produced and edited by DLA Piper*. DLA Piper acknowledges the contribution of the European PPP Expertise Centre (EPEC)** in the preparation of the Report. DLA Piper retains editorial responsibility for the Report. In contributing to the Report neither the European Investment Bank, EPEC, EPEC’s Members, nor any Contributor*** indicates or implies agreement with, or endorsement of, any part of the Report. This document is the copyright of DLA Piper and the Contributors. This document is confidential and personal to you. It is provided to you on the understanding that it is not to be re-used in any way, duplicated or distributed without the written consent of DLA Piper or the relevant Contributor. -

Welcome to Gorlice County

WELCOME TO GORLICE COUNTY © Wydawnictwo PROMO Dear Readers, The publication commissioned by I wish to invite you to the beautiful and hospitable Gorlice County located in County Head Office in Gorlice south-eastern Poland. It is a perfect place for active recreation, offering you an opportunity to experience the natural beauty of the Beskid Niski as well as the multiculturality, richness and historical diversity of our region. In the past, Bishop Karol Wojtyła – the Polish pope St. John Paul II – traversed this land on foot with young people. Participants of the 06 World Youth Days Editing: Wydawnictwo PROMO as well as many pilgrims and wayfarers continue to follow in his footsteps across the Land of Gorlice. I would like to recommend the Wooden Architecture Route, abundant in Proofreading: Catholic and Orthodox churches with as many as five entered on the UNSECO Maciej Malinowski World Heritage List. Feel invited to come and trek along the Trail of First World War Cemeteries where soldiers of many nationalities rest in peace and the Petro- Translation: leum Trail featuring the world’s first oil rigs and a place in Gorlice where Ignacy Mikołaj Sekrecki Łukasiewicz lit up the world’s first kerosene streetlamp. Be sure to visit the royal town of Biecz, with a hospital funded by Saint Queen Jadwiga and Bobowa with strong Hasidic ties. Feel invited to use the well-being facilities available in our Photography: Paweł Kutaś, health resorts Wysowa Zdrój and Wapienne as well as the lake in Klimkówka and Archive of the Culture and Promotion Centre of Bobowa Municipality (p. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

Tropy Akowskie W Poezji Jerzego Ficowskiego

Poznańskie Studia Polonistyczne Seria Literacka 20 (40) Jerzy Kandziora Tropy akowskie w poezji Jerzego Ficowskiego Pamięci Profesor Aliny Brodzkiej-Wald śledząc nurty narracji historycznej w poezji Jerzego Ficowskie- go, odnajdujemy wiele wierszy związanych z doświadczeniem jego walki w szeregach Armii Krajowej i udziału w powstaniu warszawskim. Warto zauważyć, że o ile dominujący w obrę- bie tej narracji temat zagłady żydów stanowił dla Ficowskiego niezmienne i przez wiele lat istniejące wyzwanie, aby odnaleźć sposób poe tyckiego wysłowienia zbrodni (co ostatecznie stało się w cyklu Odczytanie popiołów z 1979 r.), o tyle temat akowski został w pewien sposób odsunięty na dłuższy czas poza horyzont poe tycki autora. Dotykający tych spraw debiut Ołowiani żołnierze (1948) prześlizgnął się, rzec można, ponad historią akowską i po- wstańczą, gdzie indziej, poza owymi wątkami, osadzając znaki poetyckiej oryginalności, znamionującej już wówczas twórczość Ficowskiego. Odpowiedź na pytanie, dlaczego tak się stało, nie jest jed- noznaczna. Z różnych rozproszonych refleksji poety można odtworzyć kilka przyczyn. Powstanie warszawskie dotknęło Ficowskiego najbardziej bezpośrednio i traumatycznie. Wal- czył na Mokotowie, i tu był świadkiem śmierci swoich kolegów z oddziału. Poproszony w 1994 r. o komentarz do dziennika Bar- bary Kaczyńskiej-Januszkiewicz, która jako trzynastolatka za- pisywała wydarzenia powstania dziejące się od 1 sierpnia 1944 r. w okolicach jej domu przy ulicy Ursynowskiej 26, w tym także odnotowała pojawienie się dziewiętnastoletniego strzelca „Wra- ka”, który „poszedł zamówić trumny”, Ficowski stwierdza m.in.: „Niewiele pamiętam, walczyłem z pamięcią, bo zbyt bo- lała. [...] Wdzięczny jestem 13-letniej Basi, że utrwaliła strzępki pamięci o zapomnianym prawie przeze mnie strzelcu «Wraku», którym wówczas byłem, o moich poległych kolegach”1. -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

Moldavia and Maramureş – Micro-Destinations for Relaunching the Romanian Tourism*

Theoretical and Applied Economics Volume XVIII (2011), No. 10(563), pp. 45-56 Moldavia and Maramureş – Micro-destinations * for Relaunching the Romanian Tourism Aurelia-Felicia STĂNCIOIU Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies [email protected] Ion PÂRGARU “Polytechnica” University of Bucharest [email protected] Nicolae TEODORESCU Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies [email protected] Anca-Daniela VLĂDOI Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies [email protected] Monica Paula RAŢIU Romanian American University of Bucharest [email protected] Abstract. Since Romania holds a rich tourism heritage and a great tourism potential, the tourism division into zones was drawn up as “a possibility toward a superior and complex development of the tourism resources, in a unified vision…” (Erdeli, Gheorghilaş, 2006, p. 264), this representing a permanent concern of the specialists from all fields that are related to the tourism management. Although the criteria for selection and ranking of the tourist attractions have been the subject of some controversies, regarding the types of tourism that can be practiced in these areas, there were arrived almost unanimous conclusions. In order to ensure the representativeness and considering that all historical regions of the contemporary Romania are to the same extent micro- destinations with a substantial “tourism heritage”, the regions of Moldavia (including Bukovina) and Maramureş were merged into one for the elaboration of the research that presents, in essence, the main types of tourism and a part of the treasury of Romanian age-old heritage. Keywords: tourism destination; tourism micro-destination; destination image; regional tourism brand; type of tourism; destination marketing. JEL Code: M31. -

Urząd Miasta W Gorlicach

Piątek, 26 lipca 2019 The history of Gorlice The history of Gorlice The beginning of the town is strongly associated with the figure of Dersław I Karwacjan - Stolnik of Sandomierz, who was a Cracovian councilor and banker. In 1354 he received a royal permission from King Kazimierz the Great to establish a town near two rivers: Ropa and Sękówka. Initially, Gorlice was formed on Polish rights but at the beginning of the 15th century it was changed into Magdeburg rights. At that time Gorlice was mainly a trading town. Clothiers, shoemakers, sewers, bakers, brewers were famous not only in Cracow and in the towns of Subcarpathia, but also abroad: on the areas of today’s Slovakia. Gorlice had the privilege to organize weekly markets and big fairs twice a year which were numerously visited by Hungarian traders. In the second half of the 16th century the Odrowąży Pieniążek Family inherited Gorlice. Due to them, the town became a very important centre of Calvinism in Subcarpathia. A colloquium of three faiths: Catholicism, Calvinism and Polish Brethren took place here. In 1625, the half of the town was redeemed by Rylska Family, devoted reformers. During the Swedish Deluge, the Rylska Family took the side of the invaders, whereas the Odrowąży Pieniążek Family remained faithful to the Polish King. In 1657 a unified Swedish- Transylvanian troop destroyed the part of Gorlice which belonged to the Pieniążek Family. The war had tragic consequences - out of 1200 inhabitants only 284 people survived. In the 18th century the town started gradually developing and eventually Gorlice was redeemed by the Łętowska Family.