A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Continuing Studies and of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in Partia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Scheme

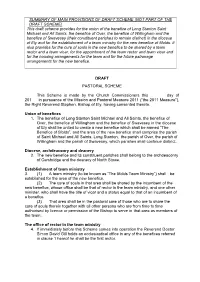

SUMMARY OF MAIN PROVISIONS OF DRAFT SCHEME (NOT PART OF THE DRAFT SCHEME) This draft scheme provides for the union of the benefice of Long Stanton Saint Michael and All Saints, the benefice of Over, the benefice of Willingham and the benefice of Swavesey (their constituent parishes to remain distinct) in the diocese of Ely and for the establishment of a team ministry for the new benefice of 5folds. It also provides for the cure of souls in the new benefice to be shared by a team rector and a team vicar, for the appointment of the team rector and team vicar and for the housing arrangements for the team and for the future patronage arrangements for the new benefice. DRAFT PASTORAL SCHEME This Scheme is made by the Church Commissioners this day of 201 in pursuance of the Mission and Pastoral Measure 2011 (“the 2011 Measure”), the Right Reverend Stephen, Bishop of Ely, having consented thereto. Union of benefices 1. The benefice of Long Stanton Saint Michael and All Saints, the benefice of Over, the benefice of Willingham and the benefice of Swavesey in the diocese of Ely shall be united to create a new benefice which shall be named “The Benefice of 5folds”, and the area of the new benefice shall comprise the parish of Saint Michael and All Saints, Long Stanton, the parish of Over, the parish of Willingham and the parish of Swavesey, which parishes shall continue distinct. Diocese, archdeaconry and deanery 2. The new benefice and its constituent parishes shall belong to the archdeaconry of Cambridge and the deanery of North Stowe. -

Mission and Pastoral Measure 2011 Draft Pastoral Church Buildings Scheme Saint Wandregesilius, Bixley in the Parish of Porlingland, Diocese of Norwich

James Davidson-Brett Pastoral Case Advisor 16/4/2021 Mission and Pastoral Measure 2011 Draft Pastoral Church Buildings Scheme Saint Wandregesilius, Bixley in the parish of Porlingland, diocese of Norwich The bishop has asked us to prepare a draft Pastoral Church Buildings Scheme in respect of pastoral proposals affecting this parish. I attach a copy of the draft Scheme and memo I am sending a copy to all the statutory interested parties, as the Mission and Pastoral Measure requires, and any others with an interest in the proposals. Anyone may make representations for or against all or any part or parts of the draft Scheme (please include the reasons for your views) preferably by email or by post to reach me no later than midnight on 19 May 2021. If we have not acknowledged receipt of your representation before this date, please ring or e- mail me to ensure it has been received. For administrative purposes, a petition will be classed as a single representation and we will only correspond with the sender of the petition, if known, or otherwise the first signatory for whom we can identify an address – “the primary petitioner”. If we do not receive representations against the draft Scheme, we will make the Scheme and it will come into effect as it provides. A copy of the completed Scheme will be sent to you together with a note of its effective date. If we receive any representations against the draft Scheme, we will send them, and any representations supporting the draft Scheme, to the Archbishop whose views will be sought. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE GERALD R. MCDERMOTT Professor of Religion and Philosophy Roanoke College Salem, VA 24153 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION: Ph.D. University of Iowa, 1989 M.R.E Grand Rapids Baptist Seminary, 1982 B.S. in History and Education, North Dakota State University, 1982 B.A. in New Testament and Early Christian Literature, University of Chicago, 1974. FELLOWSHIPS, GRANTS AND HONORS: Copenhaver Visiting Scholar Grant, to bring Hungarian literary critic Tibor Fabiny to Roanoke College for the fall of 2006, $15, 500. Institutional Renewal Grant, for 4-part lecture series on “The Lutheran Tradition” at Roanoke College, Rhodes Consultation, 2004-05, $4000. Resident Fellow, Institute for Ecumenical and Cultural Studies, Collegeville Minnesota, 2002-03. Louisville Institute, 2002-03, for sabbatical at Institute for Ecumenical and Cultural Studies. $5400. Member, Rhodes Consultation on the Future of Church-Related Colleges, 2000-03, $3500. Member, Lutheran Academy of Scholars in Higher Education, Harvard University, June 1999, $2000. Roanoke College, “Professional Achievement Award,” 1999, $1000. Member, Center of Theological Inquiry, Princeton, New Jersey, Aug. 1995–July 1996, $32,800. Virginia Foundation for Independent Colleges, Mednick Fellowship, 1995, $800, for research trip to Yale’s Beinecke Library. Presbyterian Historical Society, 1993 Woodrow Wilson Award for outstanding scholarly article: “Jonathan Edwards, the City on a Hill, and the Redeemer Nation: A Reappraisal,” $100. Selected by Roanoke College student body to give the “Last Lecture” December 1993 (first professor selected) Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture, Fellowship for Young Scholars in American Religion, 1992–93, $1000 plus expenses for four trips to Indianapolis to work with Catherine Albanese and William Hutchison. -

Mission and Pastoral Measure 2011 Diocese of Oxford Benefice of Shill Valley and Broadshire, for the Creation of a New Benefice

Mission and Pastoral Committee From the Secretary 24th October 2019 Mission and Pastoral Measure 2011 Diocese of Oxford Benefice of Shill Valley and Broadshire, for the creation of a new benefice of Black Bourton comprising the parish of Black Bourton in the diocese of Oxford, for the appointment of the first incumbent of the new benefice and for the future patronage arrangements for the new benefice. The Bishop of Oxford has asked me to publish a draft pastoral scheme in respect of pastoral proposals affecting this benefice. I enclose a copy of the draft Scheme. I am sending a copy to all the statutory interested parties, as the Mission and Pastoral Measure requires, and any others with an interest in the proposals. Anyone may make representations for or against all or any part or parts of the draft Scheme (please include the reasons for your views) in writing or by email to the Church Commissioners at the following address no later than midnight on Monday 2nd December 2019. James Davidson-Brett Church Commissioners Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3AZ (email: [email protected] / tel: 020 7898 1687) If he has not acknowledged receipt of your representation before this date, please ring or e-mail them to ensure it has been received. For administrative purposes, a petition will be classed as a single representation and the Commissioners will only correspond with the sender of the petition, if known, or otherwise the first signatory – “the primary petitioner”. If the Commissioners do not receive representations against the draft Scheme, they will make the Scheme and it will come into effect as it provides. -

Colonial Families and Their Descendants

M= w= VI= Z^r (A in Id v o>i ff (9 VV- I I = IL S o 0 00= a iv a «o = I] S !? v 0. X »*E **E *»= 6» = »*5= COLONIAL FAMILIES AND THEIR DESCENDANTS . BY ONE OF THE OLDEST GRADUATES OF ST. MARY'S HALL/BURLI^G-TiON-K.NlfJ.fl*f.'< " The first female Church-School established In '*>fOn|tSe<|;, rSJatesi-, which has reached its sixty-firstyear, and canj'pwß^vwffit-^'" pride to nearly one thousand graduates. ; founder being the great Bishop "ofBishop's^, ¦* -¦ ; ;% : GEORGE WASHINGTON .DOANE;-D^D];:)a:i-B?':i^| BALTIMORE: * PRESS :OF THE.SUN PRINTING OFFICE, ¦ -:- - -"- '-** - '__. -1900. -_ COLONIAL FAMILIES AND THEIR DESCENDANTS , BY ONE OF THE OLDEST GRADUATES OF - ST. MARY'S HALL, BURLINGTON, N. J. " The first female Church-School established in the United.States, which has reached its sixty-first year, and can point with ; pride to nearly one thousand graduates. Its.noble „* _ founder being the great Bishop ofBishops," GEORGE WASHINGTON DOANE, D.D., LL.D: :l BALTIMORE: PRESS "OF THE SUN PRINTING OFFICE, igOO. Dedication, .*«•« CTHIS BOOK is affectionately and respectfully dedicated to the memory of the Wright family of Maryland and South America, and to their descendants now livingwho inherit the noble virtues of their forefathers, and are a bright example to "all"for the same purity of character "they"possessed. Those noble men and women are now in sweet repose, their example a beacon light to those who "survive" them, guiding them on in the path of "usefulness and honor," " 'Tis mine the withered floweret most to prize, To mourn the -

The Arc of American Religious Historiography with Respect to War: William Warren Sweet's Pivotal Role in Mediating Neo-Orthodox Critique Robert A

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Arc of American Religious Historiography with Respect to War: William Warren Sweet's Pivotal Role in Mediating Neo-Orthodox Critique Robert A. Britt-Mills Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE ARC OF AMERICAN RELIGIOUS HISTORIOGRAPHY WITH RESPECT TO WAR: WILLIAM WARREN SWEET’S PIVOTAL ROLE IN MEDIATING NEO-ORTHODOX CRITIQUE By ROBERT A. BRITT-MILLS A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2012 Robert A. Britt-Mills defended this dissertation on April 18, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Amanda Porterfield Professor Directing Dissertation Neil Jumonville University Representative John Corrigan Committee Member John Kelsay Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT v 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Trends in American Religious Historiography 6 1.2 Early American Histories 8 1.3 Chapter Contents 9 2. WAR JUSTIFIED BY GOD AND NATURAL EVIDENCE: EARLY AMERICAN CHURCH HISTORIANS DESCRIBE PROTESTANT SUPPORT FOR WAR, 1702-1923 14 2.1 Cotton Mather 15 2.2 Baird, Bacon, Bacon, and Mode 18 2.2.1 Robert Baird 18 2.2.2 Leonard Bacon 27 2.2.3 Leonard Woolsey Bacon 33 2.2.4 Peter George Mode 41 2.3 Conclusion 48 3. -

Religion and the American Founding

RELIGION AND THE AMERICAN FOUNDING Ellis Sandoz ∗ I. INTRODUCTION : COMMON GROUND AND GENERAL PRINCIPLES — HOMONOIA (A RISTOTLE ) A. Federalist No. 2 (Jay) Providence has been pleased to give this one connected country to one united people—a people descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, . who . have nobly established their general liberty and independence. [I]t appears as if it was the design of Providence that an inheritance so proper and convenient for a band of brethren . should never be split into a number of unsocial, jealous, and alien sovereignties. 1 In justifying union under the Constitution, Publius (Madison) later appeals “to the great principle of self-preservation; to the transcendent law of nature and of nature’s God, which declares that the safety and happiness of society are the objects at which all political institutions aim and to which all such institutions must be sacrificed.” 2 Publius thus invokes Aristotle, Cicero, and salus populi , suprema lex esto , as often was also done by John Selden, Sir Edward Coke, and the Whigs in the 17th century constitutional debate. 3 This was understood to be the ultimate ground of all free government and basis for exercise of legitimate authority (not tyranny) over free men—the liber homo of the Magna Carta and English common law. 4 James Madison and the other founders knew and accepted this as a fundamental to their own endeavors. ∗ Hermann Moyse, Jr. Distinguished Professor of Political Science, Director of the Eric Voegelin Institute for American Renaissance Studies, Louisiana State University. -

Mission and Pastoral Committee from the Secretary 27Th June 2018

Mission and Pastoral Committee From the Secretary 27th June 2018 Mission and Pastoral Measure 2011 Diocese of Oxford Parish of Southlake St. James Parish of Woodley, St John the Evangelist The Bishop of Oxford has asked me to prepare a draft Pastoral Scheme affecting the above parishes. I enclose a copy of the draft Scheme. I am sending a copy to all the statutory interested parties, as the Mission and Pastoral Measure requires, and any others with an interest in the proposals. Anyone may make representations for or against all or any part or parts of the draft Scheme (please include the reasons for your views) in writing or by email to reach the Church Commissioners at the following address no later than midnight on Monday 13th August 2018. James Davidson-Brett Church Commissioners Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3AZ ( email james [email protected]) (tel 020 7898 1687) If they have not acknowledged receipt of your representation before this date, please ring or e-mail them to ensure it has been received. For administrative purposes, a petition will be classed as a single representation and they will only correspond with the sender of the petition, if known, or otherwise the first signatory – “the primary petitioner”. If the Commissioners do not receive representations against the draft Scheme, they will make the Scheme and it will come into effect as it provides. A copy of the completed Scheme will be sent to you together with a note of its effective date. If the Commissioners receive any representations against the draft Scheme, they will send them, and any representations supporting the draft Scheme, to the Bishop whose views will be sought. -

THE Virginia Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

GENEALOGY COLLECTION ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 833 01740 4739 GENEALOGY 975.5 V82385 1920 THE VIRGINIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Published Quarterly by THE VIRGINIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY FOR THE YEAR ENDING DECEMBER 31, 1920 VOL. XXVIII RICHMOND, VA. HOUSE OF THE SOCIETY 707 E. FRANKLIN ST. Reprinted with the permission of the original publisher KRAUS REPRINT CORPORATION New York 1968 PUBLICATION COMMITTEE E. V. VALENTINE C. V. MEREDITH Editor of the Magazine WILLIAM G. STANARD Reprinted in U.S.A. •V «9^160 TABLE OF CONTENTS Banister, John, Letter from, 1775 266 Byrd, William, First, Letters of 11 Council and General Court Minutes, 1622-29 3» 97, 219, 319 Genealogy : Aucher 285 Corbin 281, 370 Cornwallis, Wroth, Rich 375 Grymes 90, 187, 374 Lovelace 83, 176 Illustrations : Aucher Arms 285 Archer's Hope Creek, Views at 106a Gray Friars, Canterbury 88a Grymes Children 92a Grymes, Philip, Children of 92a Hall End, Warwickshire 280a Lovelace, Richard (Poet) 182a Lovelace, William 82a Lovelace, Sir William (d. 1629) 86a Lovelace, Sir William (d. 1627) 176a McCabe, William Gordon Frontispiece, July No. Northern Neck, Map of Boundaries, Frontispiece, October No. McCabe, President William Gordon, Announcement of death, January No. McCabe, William Gordon, A Brief Memoir, By A. C. Gordon 195 Mecklenburg Co., Va., Resolutions, 1774 54 Northampton Co., Land Certificates for 142 Northern Neck, Documents Relative to Boundaries of 297 Notes and Queries 65, 161, 274, 361 Orange County Marriages 152, 256, 360 Preston Papers 109, 241, 346 Virginia Gleanings in England (Wills) 26, 128, 235, 340 Virginia Historical Society, Officers and Members, January 1920, April No. -

Regent University Law Review

REGENT UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 20 2007-2008 NUMBER 1 CONTENTS ADDRESSES THE EVOLUTION OF VIRGINIA'S CONSTITUTIONS: A CELEBRATION OF THE RULE OF LAW IN AMERICA Leroy Rountree Hassell, Sr. 1 RELIGION AND THE AMERICAN FOUNDING Ellis Sandoz 17 RELIGION AND LIBERTY UNDER LAW AT THE FOUNDING OF AMERICA Harold J. Berman 31 ARTICLES JUSTICE THOMAS AND PARTIAL INCORPORATION OF THE ESTABLISHMENT CLAUSE: HEREIN OF STRUCTURAL LIMITATIONS, LIBERTY INTERESTS, AND TAKING INCORPORATION SERIOUSLY Richard F. Duncan 37 REPUBLICANISM AND RELIGION: SOME CONTEXTUAL CONSIDERATIONS Ellis Sandoz 57 REGENT UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW Volume 20 2007-2008 Number 1 Editor-in-Chief JOHN LEGG BOARD OF EDITORS Executive Editor JAIRED B. HALL Managing Editor Managing Editor VALERIE H. KUNTZ CORT I. WALKER Articles Editor Articles Editor TIMOTHY L. CREED ZACHARY CUMMINGS Symposium Editor Business Manager JODI LYNN FOSS NATHANIEL L. STORY Notes and Comments Editor Notes and Comments Editor LEO MARVIN LESTINO MELISSA K. DEEM Senior Editor Senior Editor LISA A. BIRON STEPHEN D. CASEY Senior Editor AMBER D. WOOTTON STAFF R. SCOTT ADAMS ROBERTA J. GANTEA TIFFANY N. BARRANS ERIN K. MCCORMICK BRANDON J. CARR VALERIE S. PAYNE LAURA L. DAVIDS JONATHAN PENN ELIZABETH E. FABICK MICHELLE R. RIEL BETHANY FLITON J. SCOTT TALBERT AMANDA K. FREEMAN FACULTY ADVISOR DAVID M. WAGNER EDITORIAL ADVISOR JAMES J. DUANE NOTES DOCKING THE TAIL THAT WAGS THE DOG: WHY CONGRESS SHOULD ABOLISH THE USE OF ACQUITTED CONDUCT AT SENTENCING AND How COURTS SHOULD TREAT ACQUITTED CONDUCT AFTER UNITED STATES V. BOOKER FarnazFarkish 101 GALLOWAY, SPLIT-INTEREST TRUSTS, AND UNDIVIDED PORTIONS: DOES DISALLOWING THE CHARITABLE CONTRIBUTION DEDUCTION OVERSTEP LEGISLATIVE INTENT? Valerie H. -

JONATHAN EDWARDS' RHETORIC of HISTORY by Juan Sánchez

IMMEDIATE AND PROGRESSIVE DIVINE AGENCY: JONATHAN EDWARDS’ RHETORIC OF HISTORY by Juan Sánchez Naffziger BA, University of Seville, 2005 MA, University of Seville, 2010 A DISSERTATION Submitted to the faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English and North American Literature Concentration in American Studies at the University of Seville Seville, Spain April 2015 Acknowledgements The following dissertation would never have been completed without the continued encouragement and invaluable help of professor Ramón Espejo Romero. He has been instrumental (providential, if I may put it in more Edwardsean terms) in bringing about the final result in more ways than the ‘mere’ revision and correction of the text. It was through a scholarship offered by the department he is currently the Director of that I was able to come to the United States, where I have found the time and inspiration to finish my readings and dissertation writing. Had Dr. Espejo not prompted me to go for the ‘American experience’, I probably would never have finished the following study. I certainly would not have been able to include or consult many of the works (recent scholarly studies on Jonathan Edwards, old letters and sermons, etc.) that have been made available to me at UNC Chapel Hill, and which now make up what I believe is a solid bibliography. My most grateful recognition and special thanks, therefore, to this excellent professor of North American literature at the University of Seville, Spain. The love and support of my wife through the last five years, as I locked myself away to read and write during Christmas, Easter and summer holidays, deserve the deepest thanks. -

The Beda Review 2018 - 2019 the Beda Review

The Beda Review 2018 - 2019 The Beda Review Pontificio Collegio Beda Viale di San Paolo 18 00146 Roma Tel: + 39 06 5512 71 Fax: + 39 06 5512 Website: www.bedacollege.org Facebook: www.facebook.com/The-Pontifical-Beda-College-272626833130878 Twitter: www.twitter.com/@pontificalbeda Editor Fr Alan Hodgson Associate Editor Br Markus Ohlsson TOR Photographers Fr Alan Hodgson and Br Markus Ohlsson TOR Design and print Pixelpress Ltd Publishing Consultant Fergus Mulligan Communications www.publishing.ie Front cover: The last two windows in the Beda College chapel by the stained glass artist, Lucia Larreta, will be a familiar sight to anyone who has visited the College but especially to former students who spend so much of their time in valuable contemplation beneath these beautiful windows. They depict A Holy Priesthood and The heavenly banquet respectively. Back Cover: A bronze of St Bede commissioned by the College and crafted by James Davidson (www.ajdsculptors.co.uk). A copy of this bronze was presented to Professor Karen Kilby, holder of the Bede Chair of Catholic Theology at Durham University, after the first Bede Lecture held at the College in the first semester of this academic year. 2 The Beda Review 2018-2019 Contents Rector’s Report 5 Editorial 12 Features Homily for the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity 2019 - Fr John O’Toole 14 Bartimaeus, the Blind Beggar - Rev. Norm Allred 19 Cucina Romana - Fr Ronald Campbell 21 Religious music but not in church - Rev. Adrian Lowe 25 A Jewish perspective on New testament Interpretation - Sr