Hymenoptera: Chrysididae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nordiska Vägsteklar, Pompilidae. Johan Abenius. De Svenska

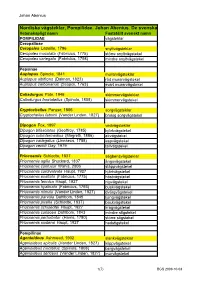

Johan Abenius Nordiska vägsteklar, Pompilidae. Johan Abenius. De svenska namnen fastställda av Kommittén för svenska djurnamn 100825 Vetenskapligt namn Fastställt svenskt namn POMPILIDAE vägsteklar Ceropalinae Ceropales Latreille, 1796 snyltvägsteklar Ceropales maculata (Fabricius, 1775) större snyltvägstekel Ceropales variegata (Fabricius, 1798) mindre snyltvägstekel Pepsinae Auplopus Spinola, 1841 murarvägsteklar Auplopus albifrons (Dalman, 1823) röd murarvägstekel Auplopus carbonarius (Scopoli, 1763) svart murarvägstekel Caliadurgus Pate, 1946 skimmervägsteklar Caliadurgus fasciatellus (Spinola, 1808) skimmervägstekel Cryptocheilus Panzer, 1806 sorgvägsteklar Cryptocheilus fabricii (Vander Linden, 1827) brokig sorgvägstekel Dipogon Fox, 1897 vedvägsteklar Dipogon bifasciatus (Geoffroy, 1785) björkvägstekel Dipogon subintermedius (Magretti, 1886) ekvägstekel Dipogon variegatus (Linnaeus, 1758) aspvägstekel Dipogon vechti Day, 1979 tallvägstekel Priocnemis Schiødte, 1837 sågbensvägsteklar Priocnemis agilis Shuckard, 1837 ängsvägstekel Priocnemis confusor Wahis, 2006 stäppvägstekel Priocnemis cordivalvata Haupt, 1927 hjärtvägstekel Priocnemis exaltata (Fabricius, 1775) höstvägstekel Priocnemis fennica Haupt, 1927 nipvägstekel Priocnemis hyalinata (Fabricius, 1793) buskvägstekel Priocnemis minuta (Vander Linden, 1827) dvärgvägstekel Priocnemis parvula Dahlbom, 1845 ljungvägstekel Priocnemis pusilla (Schiødte, 1837) backvägstekel Priocnemis schioedtei Haupt, 1927 kragvägstekel Priocnemis coriacea Dahlbom, 1843 mindre stigstekel Priocnemis -

Hymenoptera: Pompilidae) of Different Forest Habitats in the National Park Keller- Wald-Edersee (Germany, Hessen)

©Ampulex online, Christian Schmid-Egger; download unter http://www.ampulex.de oder www.zobodat.at AMPULEX 4|2012 Fuhrmann: Wegwespen des Nationalparks Kellerwald-Edersee Die Wegwespenfauna (Hymenoptera: Pompi- lidae) unterschiedlicher Waldstandorte des Nationalparks Kellerwald-Edersee Markus Fuhrmann Zum Großen Wald 19 | 57223 Kreuztal | Germany | [email protected] Zusammenfassung Es werden Ergebnisse der Untersuchung von Wegwespen drei verschiedener Waldstandorte des Nationalparks Kellerwald-Edersee vorgestellt. Während zwei der drei Wälder typische bodensaure Buchenwaldstandorte unterschiedlichen Alters verkörpern, ist der dritte Standort ein steiler Eichengrenzwald, der stark mit Kiefern bewachsen ist. Insgesamt kommen Daten von 717 gefangenen Individuen in 17 Arten zur Auswertung. Die Fauna setzt sich auf den bodensauren Buchenwaldstandorten aus weit verbreiteten euryöken Wegwespen zusammen. Auffällig ist, dass allein 628 Wegwespen in 14 Arten von einer isolierten Windwurffläche des Sturmes Kyrill stammen. Demgegenüber konnten in einem sehr alten, aufgelichteten Buchenwald nur 56 Exemplare in fünf Arten gefangen werden. Wegwespen haben in aufgelichte- ten, „urwaldähnlichen“ Buchenwäldern ihr Aktivitätsmaximum in den Frühjahrsmonaten. Auf Lichtungen hingegen kommen neben Frühjahrsarten auch Hochsommer-Pompiliden vor. Es zeigte sich, dass das Vorkommen der Pompiliden im Wesentlichen durch ein für die Entwicklung der Larven geeignetes Mikroklima innerhalb des Waldes bestimmt wird, und weniger durch die Spinnendichte und die Verfügbarkeit von Nestrequisiten. Summary Markus Fuhrmann: The fauna of Spider Wasps (Hymenoptera: Pompilidae) of different forest habitats in the National Park Keller- wald-Edersee (Germany, Hessen). Pompilid wasps were studied in three different forest types in the Nationalpark Kellerwald-Edersee (Germany, Hesse, Waldeck-Frankenberg). Two woods were red beech forests, the third was a boundary oak wood. The oak wood yet was dominated by pines. -

Lepidoptera, Zygaenidae

©Ges. zur Förderung d. Erforschung von Insektenwanderungen e.V. München, download unter www.zobodat.at _______Atalanta (Dezember 2003) 34(3/4):443-451, Würzburg, ISSN 0171-0079 _______ Natural enemies of burnets (Lepidoptera, Zygaenidae) 2nd Contribution to the knowledge of hymenoptera paraziting burnets (Hymenoptera: Braconidae, Ichneumonidae, Chaleididae) by Tadeusz Kazmierczak & J erzy S. D ^browski received 18.VIII.2003 Abstract: New trophic relationships between Braconidae, Ichneumonidae, Chaleididae, Pteromalidae, Encyrtidae, Torymidae, Eulophidae (Hymenoptera) and burnets (Lepidoptera, Zygaenidae) collected in selected regions of southern Poland are considered. Introduction Over 30 species of insects from the family Zygaenidae (Lepidoptera) occur in Central Europe. The occurrence of sixteen of them was reported in Poland (D/^browski & Krzywicki , 1982; D/^browski, 1998). Most of these species are decidedly xerothermophilous, i.e. they inhabit dry, open and strongly insolated habitats. Among the species discussed in this paperZygaena (Zygaena) angelicae O chsenheimer, Z. (Agrumenia) carniolica (Scopoli) and Z (Zygaena) loti (Denis & Schiffermuller) have the greatest requirements in this respect, and they mainly live in dry, strongly insolated grasslands situated on lime and chalk subsoil. The remaining species occur in fresh and moist habitats, e. g. in forest meadows and peatbogs. Due to overgrowing of the habitats of these insects with shrubs and trees as a result of natural succession and re forestation, or other antropogenic activities (urbanization, land reclamation) their numbers decrease, and they become more and more rare and endangered. During many years of investigations concerning the family Zygaenidae their primary and secondary parasitoids belonging to several families of Hymenoptera were reared. The host species were as follows: Adscita (Adscita) statices (L.), Zygaena (Mesembrynus) brizae (Esper), Z (Mesembrynus) minos (Denis & Schiffermuller), Z. -

Towards Simultaneous Analysis of Morphological and Molecular Data in Hymenoptera

Towards simultaneous analysis of morphological and molecular data in Hymenoptera JAMES M. CARPENTER &WARD C. WHEELER Accepted 5 January 1999 Carpenter, J. M. & W. C. Wheeler. (1999). Towards simultaneous analysis of molecular and morphological data in Hymenoptera. Ð Zoologica Scripta 28, 251±260. Principles and methods of simultaneous analysis in cladistics are reviewed, and the first, preliminary, analysis of combined molecular and morphological data on higher level relationships in Hymenoptera is presented to exemplify these principles. The morphological data from Ronquist et al. (in press) matrix, derived from the character diagnoses of the phylogenetic tree of Rasnitsyn (1988), are combined with new molecular data for representatives of 10 superfamilies of Hymenoptera by means of optimization alignment. The resulting cladogram supports Apocrita and Aculeata as groups, and the superfamly Chrysidoidea, but not Chalcidoidea, Evanioidea, Vespoidea and Apoidea. James M. Carpenter, Department of Entomology, and Ward C. Wheeler, Department of Invertebrates, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024, U SA. E-mail: [email protected] Introduction of consensus techniques to the results of independent Investigation of the higher-level phylogeny of Hymenoptera analysis of multiple data sets, as for example in so-called is at a very early stage. Although cladistic analysis was ®rst `phylogenetic supertrees' (Sanderson et al. 1998), does not applied more than 30 years ago, in an investigation of the measure the strength of evidence supporting results from ovipositor by Oeser (1961), a comprehensive analysis of all the different data sources Ð in addition to other draw- the major lineages remains to be done. -

Final Report 1

Sand pit for Biodiversity at Cep II quarry Researcher: Klára Řehounková Research group: Petr Bogusch, David Boukal, Milan Boukal, Lukáš Čížek, František Grycz, Petr Hesoun, Kamila Lencová, Anna Lepšová, Jan Máca, Pavel Marhoul, Klára Řehounková, Jiří Řehounek, Lenka Schmidtmayerová, Robert Tropek Březen – září 2012 Abstract We compared the effect of restoration status (technical reclamation, spontaneous succession, disturbed succession) on the communities of vascular plants and assemblages of arthropods in CEP II sand pit (T řebo ňsko region, SW part of the Czech Republic) to evaluate their biodiversity and conservation potential. We also studied the experimental restoration of psammophytic grasslands to compare the impact of two near-natural restoration methods (spontaneous and assisted succession) to establishment of target species. The sand pit comprises stages of 2 to 30 years since site abandonment with moisture gradient from wet to dry habitats. In all studied groups, i.e. vascular pants and arthropods, open spontaneously revegetated sites continuously disturbed by intensive recreation activities hosted the largest proportion of target and endangered species which occurred less in the more closed spontaneously revegetated sites and which were nearly absent in technically reclaimed sites. Out results provide clear evidence that the mosaics of spontaneously established forests habitats and open sand habitats are the most valuable stands from the conservation point of view. It has been documented that no expensive technical reclamations are needed to restore post-mining sites which can serve as secondary habitats for many endangered and declining species. The experimental restoration of rare and endangered plant communities seems to be efficient and promising method for a future large-scale restoration projects in abandoned sand pits. -

The Linsenmaier Chrysididae Collection Housed in the Natur-Museum Luzern (Switzerland) and the Main Results of the Related GBIF Hymenoptera Project (Insecta)

Zootaxa 3986 (5): 501–548 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3986.5.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:0BC8E78B-2CB2-4DBD-B036-5BE1AEC4426F The Linsenmaier Chrysididae collection housed in the Natur-Museum Luzern (Switzerland) and the main results of the related GBIF Hymenoptera Project (Insecta) PAOLO ROSA1, 2, 4, MARCO VALERIO BERNASCONI1 & DENISE WYNIGER1, 3 1Natur-Museum Luzern, Kasernenplatz 6, CH-6003 Luzern, Switzerland 2Private address: Via Belvedere 8/d I-20881 Bernareggio (MB), Italy 3present address: Naturhistorisches Museum Basel, Augustinergasse 2, CH-4001 Basel, Switzerland 4Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Table of contents Abstract . 501 Introduction . 502 Linsenmaier's Patrimony . 502 Historical overview . 503 The Linsenmaier Chrysididae collection . 506 Material and methods . 507 GBIF project . 507 The reorganization of the Linsenmaier collection . 508 Manuscripts . 513 Observations on some specimens and labels found in the collection . 515 Type material . 519 New synonymies . 524 Conclusions . 525 Acknowledgements . 525 References . 525 APPENDIX A . 531 Species-group names described by Walter Linsenmaier. 531 Replacement names given by Linsenmaier . 543 Unnecessary replacement names given by Linsenmaier . 543 Genus-group names described by Linsenmaier . 544 Replacement names in the genus-group names . 544 APPENDIX B . 544 List of the types housed in Linsenmaier's -

Hymenoptera, Chrysididae)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 669: 65–88 (2017) Chinese Chrysis 65 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.669.12398 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research One new species and three new records of Chrysis Linnaeus from China (Hymenoptera, Chrysididae) Paolo Rosa1, Na-sen Wei2, Zai-fu Xu2 1 Via Belvedere 8/d, I-20881 Bernareggio (MB), Italy 2 Department of Entomology, College of Agriculture, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510640, China Corresponding author: Zai-fu Xu ([email protected]) Academic editor: M. Ohl | Received 24 February 2017 | Accepted 29 March 2017 | Published 21 April 2017 http://zoobank.org/30DD0C5B-6A72-494B-834F-ECF3544DE8BC Citation: Rosa P, Wei N-s, Xu Z-f (2017) One new species and three new records of Chrysis Linnaeus from China (Hymenoptera, Chrysididae). ZooKeys 669: 65–88. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.669.12398 Abstract Four Chinese Chrysis species-groups, the antennata, capitalis, elegans, and maculicornis species-groups, are discussed. Chrysis lapislazulina Rosa & Xu, sp. n. is described in the elegans species-group; and three spe- cies, C. brachyceras Bischoff, 1910, C. subdistincta Linsenmaier, 1968 and C. yoshikawai Tsuneki, 1961, are reported for the first time from China in other species-groups. A new synonymy is proposed for C. ignifascia Mocsáry, 1893 = C. taiwana Tsuneki, 1970, syn. n. A short historical review of the elegans species-group is provided. C. goetheana Semenov, 1967 is transferred from the elegans species-group to the maculicornis species-group. C. mesochlora Mocsáry, 1893 is considered a nomen dubium. Keywords Chrysis, antennata species-group, capitalis species-group, elegans species-group, maculicornis species-group, new species, new records, China Introduction Kimsey and Bohart (1991) provided keys and detailed diagnoses for the identification of Chrysis species-groups from all zoogeographical regions. -

New Records and Three New Species of Chrysididae (Hymenoptera, Chrysidoidea) from Iran

Journal of Insect Biodiversity 3(15): 1-32, 2015 http://www.insectbiodiversity.org RESEARCH ARTICLE New records and three new species of Chrysididae (Hymenoptera, Chrysidoidea) from Iran Franco Strumia1 Majid Fallahzadeh2* 1Physics Department, Pisa University, L. Pontecorvo, 3 – 56127 Pisa, Italy, e-mail: [email protected] 2*Department of Entomology, Jahrom Branch, Islamic Azad University, Jahrom, Iran. *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub: 77510A1B-DFE3-430A-9DBF-E0ECB1FDE068 1urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author: 88DF3BBA-90B2-4E95-A3AC-6805002E56CE 2urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author: CAEC6969-40E2-451C-A6D4-89435348C03B Abstract: Data on the distribution of 52 cuckoo wasp species (Hymenoptera, Chrysididae) from Iran are given. One genus and 27 species (including 3 new species: 52% of the captured material) are new records for the country. In addition, three new species, Chrysis gianassoi sp. nov., Chrysis majidi sp. nov. and Chrysis unirubra sp. nov. are described and illustrated, and diagnostic characters are provided to identify them. Chrysis turcica du Buyson, 1908 is removed from synonymy with Chrysis peninsularis du Buysson, 1887. Chrysis bilobata Balthasar, 1953 is confirmed as valid species and illustrated. The composition of the Iranian Chrysididae fauna is compared with that of South Palaearctic countries. The large proportion of new record and new species (≈52%) indicates that the fauna of Iranian Chrysididae is rich and diverse but has not yet been thoroughly studied. The majority of new record were obtained from mountainous sites above 1000 m above sea level, indicating the rich biodiversity of this biotope. Key words: Chrysididae, malaise trap, pan trap, Palaearctic Region, taxonomy, fauna, Iran. -

Nr. 10 ISSN 2190-3700 Nov 2018 AMPULEX 10|2018

ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR ACULEATE HYMENOPTEREN AMPULEXJOURNAL FOR HYMENOPTERA ACULEATA RESEARCH Nr. 10 ISSN 2190-3700 Nov 2018 AMPULEX 10|2018 Impressum | Imprint Herausgeber | Publisher Dr. Christian Schmid-Egger | Fischerstraße 1 | 10317 Berlin | Germany | 030-89 638 925 | [email protected] Rolf Witt | Friedrichsfehner Straße 39 | 26188 Edewecht-Friedrichsfehn | Germany | 04486-9385570 | [email protected] Redaktion | Editorial board Dr. Christian Schmid-Egger | Fischerstraße 1 | 10317 Berlin | Germany | 030-89 638 925 | [email protected] Rolf Witt | Friedrichsfehner Straße 39 | 26188 Edewecht-Friedrichsfehn | Germany | 04486-9385570 | [email protected] Grafik|Layout & Satz | Graphics & Typo Umwelt- & MedienBüro Witt, Edewecht | Rolf Witt | www.umbw.de | www.vademecumverlag.de Internet www.ampulex.de Titelfoto | Cover Colletes perezi ♀ auf Zygophyllum fonanesii [Foto: B. Jacobi] Colletes perezi ♀ on Zygophyllum fonanesii [photo: B. Jacobi] Ampulex Heft 10 | issue 10 Berlin und Edewecht, November 2018 ISSN 2190-3700 (digitale Version) ISSN 2366-7168 (print version) V.i.S.d.P. ist der Autor des jeweiligen Artikels. Die Artikel geben nicht unbedingt die Meinung der Redaktion wieder. Die Zeitung und alle in ihr enthaltenen Texte, Abbildungen und Fotos sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Das Copyright für die Abbildungen und Artikel liegt bei den jeweiligen Autoren. Trotz sorgfältiger inhaltlicher Kontrolle übernehmen wir keine Haftung für die Inhalte externer Links. Für den Inhalt der verlinkten Seiten sind ausschließlich deren Betreiber verantwortlich. All rights reserved. Copyright of text, illustrations and photos is reserved by the respective authors. The statements and opinions in the material contained in this journal are those of the individual contributors or advertisers, as indicated. The publishers have used reasonab- le care and skill in compiling the content of this journal. -

Zootaxa, Fossil Eucharitidae and Perilampidae

Zootaxa 2306: 1–16 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Fossil Eucharitidae and Perilampidae (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) from Baltic Amber JOHN M. HERATY1 & D. CHRISTOPHER DARLING2 1Department of Entomology, University of California, Riverside, CA, USA, 92521. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Entomology, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 2C6 and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 1A. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Palaeocharis rex n. gen. and sp. (Eucharitidae: Eucharitinae) and Perilampus pisticus n. sp. (Perilampidae: Perilampinae) are described from Baltic amber. Perilampus renzii (Peñalver & Engel) is transferred to Torymidae: Palaeotorymus renzii n. comb. Palaeocharis is related to Psilocharis Heraty based on presence of one anellus, linear mandibular depression, dorsal axillular groove, free prepectus and a transverse row of hairs on the hypopygium. This fossil is unique in comparison with extant Chalcidoidea because there are two foretibial spurs instead of a single well- developed calcar. Perilampus pisticus is placed into the extant Perilampus micans group because the frenum and marginal rim of the scutellum are visible in dorsal view and the prepectus forms a large equilateral triangle. The phylogenetic placement of both genera is discussed based on an analysis of both a combined morphological and molecular (28S and 18S) and morphology-only matrix. Morphological characters were used from an earlier study of Eucharitidae (Heraty 2002), with some characters revised to reflect variation in Perilampinae. Baltic amber is of Eocene age, which puts the age of divergence of these families at more than 40 mya. -

Chalcid Forum Chalcid Forum

ChalcidChalcid ForumForum A Forum to Promote Communication Among Chalcid Workers Volume 23. February 2001 Edited by: Michael E. Schauff, E. E. Grissell, Tami Carlow, & Michael Gates Systematic Entomology Lab., USDA, c/o National Museum of Natural History Washington, D.C. 20560-0168 http://www.sel.barc.usda.gov (see Research and Documents) minutes as she paced up and down B. sarothroides stems Editor's Notes (both living and partially dead) antennating as she pro- gressed. Every 20-30 seconds, she would briefly pause to Welcome to the 23rd edition of Chalcid Forum. raise then lower her body, the chalcidoid analog of a push- This issue's masthead is Perissocentrus striatululus up. Upon approaching the branch tips, 1-2 resident males would approach and hover in the vicinity of the female. created by Natalia Florenskaya. This issue is also Unfortunately, no pre-copulatory or copulatory behaviors available on the Systematic Ent. Lab. web site at: were observed. Naturally, the female wound up leaving http://www.sel.barc.usda.gov. We also now have with me. available all the past issues of Chalcid Forum avail- The second behavior observed took place at Harshaw able as PDF documents. Check it out!! Creek, ~7 miles southeast of Patagonia in 1999. Jeremiah George (a lepidopterist, but don't hold that against him) and I pulled off in our favorite camping site near the Research News intersection of FR 139 and FR 58 and began sweeping. I knew that this area was productive for the large and Michael W. Gates brilliant green-blue O. tolteca, a parasitoid of Pheidole vasleti Wheeler (Formicidae) brood. -

Hymenoptera: Chrysididae) in Estonia Ascertained with Trap-Nesting

Eur. J. Entomol. 112(1): 91–99, 2015 doi: 10.14411/eje.2015.012 ISSN 1210-5759 (print), 1802-8829 (online) Host specificity of the tribe Chrysidini (Hymenoptera: Chrysididae) in Estonia ascertained with trap-nesting MADLI PÄRN 1, VILLU SOON 1, 2, *, TUULI VALLISOO 1, KRISTIINA HOVI 1 and JAAN LUIG 2 1 Department of Zoology, Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences, University of Tartu, Vanemuise 46, Tartu 51014, Estonia; e-mails: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Zoological Museum, Natural History Museum, University of Tartu, Vanemuise 46, 51014 Tartu, Estonia; e-mail: [email protected] Key words. Hymenoptera, Chrysididae, cuckoo wasps, parasite specialization, trap nest, Chrysis, host specificity Abstract. Cuckoo wasps (Chrysididae) are a medium-sized and widespread family of Hymenoptera whose species are generally para- sitoids or cleptoparasites of solitary wasps and bees. The identities of the hosts are known from various studies and occasional records; however the utility of such data is often low due to unstable taxonomy of the species and the inappropriate methods used to determine the host species. Therefore, despite numerous publications on the subject, the host-parasite relationships of cuckoo wasps are poorly understood. Moreover, a revision of existing literature reveals that cuckoo wasps are often unreasonably considered to be unspecialized (i.e., sharing host species). In this study we use an accurate method (trap-nests) to determine the host relationships of Estonian cuckoo wasps of the genera Chrysis and Trichrysis and determine their level of specialization. 568 trap nest bundles (each containing 15–20 single reed stems) were established at 361 locations across Estonia during the vegetation periods of 2009–2011.