“Hmmronk, Skrrrrape, Schttttokke”. Searching for Automatism in Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs in the Key of Z: the Curious Universe of Outsider Music Free

FREE SONGS IN THE KEY OF Z: THE CURIOUS UNIVERSE OF OUTSIDER MUSIC PDF Irwin Chusid | 272 pages | 01 Apr 2000 | A Cappella Books | 9781556523724 | English | Los Angeles, CA, United States Songs in the Key of Z | Chicago Review Press If VH1's Behind the Music were as interesting as Chusid's first, and reportedly last, book, this reviewer would never leave his apartment. A record producer, music historian, and host of WFMU's Irwin Chusid. Outsider musicians can be the product of damaged DNA, alien abduction, drug fry, demonic possession, or simply sheer obliviousness. This book profiles dozens of outsider musicians, both prominent and obscure—figures such as The Shaggs, Syd Barrett, Tiny Tim, Jandek, Captain Beefheart, Daniel Johnston, Songs in the Key of Z: The Curious Universe of Outsider Music Partch, and The Legendary Stardust Cowboy—and presents their strange life stories along with photographs, interviews, cartoons, and discographies. About the only things these self-taught artists have in common are an utter lack of conventional tunefulness and an overabundance of earnestness and passion. But, believe it or not, they're worth listening to, often outmatching all contenders for inventiveness and originality. A CD featuring songs by artists profiled in the book is also available. Syd Barrett 21 Snapshots in Sound. The Shaggs 12 Eilert Pilarm. "Songs in the Key of Z" by Irwin Chusid | The Curious Universe of Outsider Music Presidents' Day. Veterans Day. Shopping Cart Checkout. Follow Us. Audio Downloads. Activity Kit. Songs in the Key of Z. Overview Reviews Author Biography Overview Outsider musicians can be the product Songs in the Key of Z: The Curious Universe of Outsider Music damaged DNA, alien abduction, drug fry, demonic possession, or simply sheer obliviousness. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

Punk Aesthetics in Independent "New Folk", 1990-2008

PUNK AESTHETICS IN INDEPENDENT "NEW FOLK", 1990-2008 John Encarnacao Student No. 10388041 Master of Arts in Humanities and Social Sciences University of Technology, Sydney 2009 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Tony Mitchell for his suggestions for reading towards this thesis (particularly for pointing me towards Webb) and for his reading of, and feedback on, various drafts and nascent versions presented at conferences. Collin Chua was also very helpful during a period when Tony was on leave; thank you, Collin. Tony Mitchell and Kim Poole read the final draft of the thesis and provided some valuable and timely feedback. Cheers. Ian Collinson, Michelle Phillipov and Diana Springford each recommended readings; Zac Dadic sent some hard to find recordings to me from interstate; Andrew Khedoori offered me a show at 2SER-FM, where I learnt about some of the artists in this study, and where I had the good fortune to interview Dawn McCarthy; and Brendan Smyly and Diana Blom are valued colleagues of mine at University of Western Sydney who have consistently been up for robust discussions of research matters. Many thanks to you all. My friend Stephen Creswell’s amazing record collection has been readily available to me and has proved an invaluable resource. A hearty thanks! And most significant has been the support of my partner Zoë. Thanks and love to you for the many ways you helped to create a space where this research might take place. John Encarnacao 18 March 2009 iii Table of Contents Abstract vi I: Introduction 1 Frames -

Sretenovic Dejan Red Horizon

Dejan Sretenović RED HORIZON EDITION Red Publications Dejan Sretenović RED HORIZON AVANT-GARDE AND REVOLUTION IN YUGOSLAVIA 1919–1932 kuda.org NOVI SAD, 2020 The Social Revolution in Yugoslavia is the only thing that can bring about the catharsis of our people and of all the immorality of our political liberation. Oh, sacred struggle between the left and the right, on This Day and on the Day of Judgment, I stand on the far left, the very far left. Be‑ cause, only a terrible cry against Nonsense can accelerate the whisper of a new Sense. It was with this paragraph that August Cesarec ended his manifesto ‘Two Orientations’, published in the second issue of the “bimonthly for all cultural problems” Plamen (Zagreb, 1919; 15 issues in total), which he co‑edited with Miroslav Krleža. With a strong dose of revolutionary euphoria and ex‑ pressionistic messianic pathos, the manifesto demonstrated the ideational and political platform of the magazine, founded by the two avant‑garde writers from Zagreb, activists of the left wing of the Social Democratic Party of Croatia, after the October Revolution and the First World War. It was the struggle between the two orientations, the world social revolution led by Bolshevik Russia on the one hand, and the world of bourgeois counter‑revolution led by the Entente Forces on the other, that was for Cesarec pivot‑ al in determining the future of Europe and mankind, and therefore also of the newly founded Kingdom of Serbs, Cro‑ ats and Slovenes (Kingdom of SCS), which had allied itself with the counter‑revolutionary bloc. -

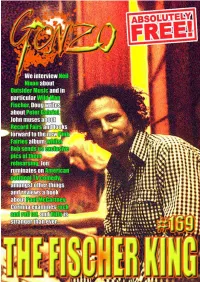

Gonzo Weekly #169

Subscribe to Gonzo Weekly http://eepurl.com/r-VTD Subscribe to Gonzo Daily http://eepurl.com/OvPez Gonzo Facebook Group https://www.facebook.com/groups/287744711294595/ Gonzo Weekly on Twitter https://twitter.com/gonzoweekly Gonzo Multimedia (UK) http://www.gonzomultimedia.co.uk/ Gonzo Multimedia (USA) http://www.gonzomultimedia.com/ 3 is euphemistically known as 'The Festive Season', and there was one week we didn't come out because British Telecom had managed to screw up our internet coverage, but apart from those, we have come out every week now for the past 169 weeks, and that truly does blow my mind somewhat when I think about it. I have always vaguely been a Dr Who fan, and although I don't think that stylistically or emotionally it has reached the heights that it did with Jon Pertwee, and even Patrick Troughton back in the day, I have followed much of the series since it came back in 2005. I lost interest half way through David Tennant's tenure in the driving seat of the TARDIS and only came back on board half way through whatshisface's seasons, but I have been massively impressed by Dear Friends, Peter Capaldi, who has brought back the curmudgeonly element that I feel has been Welcome to another issue of the magazine, which missing from the role in recent years. each issue I reiterate that I am not just proud to be the editor of, but that it never ceases to amaze me I lost interest in Dr Who for some years mainly that it has been going for so many weeks without because I had a lodger who was so irritating about a break. -

Download File

Eastern European Modernism: Works on Paper at the Columbia University Libraries and The Cornell University Library Compiled by Robert H. Davis Columbia University Libraries and Cornell University Library With a Foreword by Steven Mansbach University of Maryland, College Park With an Introduction by Irina Denischenko Georgetown University New York 2021 Cover Illustration: No. 266. Dvacáté století co dalo lidstvu. Výsledky práce lidstva XX. Věku. (Praha, 1931-1934). Part 5: Prokroky průmyslu. Photomontage wrappers by Vojtěch Tittelbach. To John and Katya, for their love and ever-patient indulgence of their quirky old Dad. Foreword ©Steven A. Mansbach Compiler’s Introduction ©Robert H. Davis Introduction ©Irina Denischenko Checklist ©Robert H. Davis Published in Academic Commons, January 2021 Photography credits: Avery Classics Library: p. vi (no. 900), p. xxxvi (no. 1031). Columbia University Libraries, Preservation Reformatting: Cover (No. 266), p.xiii (no. 430), p. xiv (no. 299, 711), p. xvi (no. 1020), p. xxvi (no. 1047), p. xxvii (no. 1060), p. xxix (no. 679), p. xxxiv (no. 605), p. xxxvi (no. 118), p. xxxix (nos. 600, 616). Cornell Division of Rare Books & Manuscripts: p. xv (no. 1069), p. xxvii (no. 718), p. xxxii (no. 619), p. xxxvii (nos. 803, 721), p. xl (nos. 210, 221), p. xli (no. 203). Compiler: p. vi (nos. 1009, 975), p. x, p. xiii (nos. 573, 773, 829, 985), p. xiv (nos. 103, 392, 470, 911), p. xv (nos. 1021, 1087), p. xvi (nos. 960, 964), p. xix (no. 615), p. xx (no. 733), p. xxviii (no. 108, 1060). F.A. Bernett Rare Books: p. xii (nos. 5, 28, 82), p. -

The Local 518 Music (And More) Report 2018 – Quarter 1

The Local 518 Music (and More) Report 2018 – Quarter 1 This report covers the time period of January 1st to Rock / Pop March 31st, 2017. We inadvertently missed a few before Ampevene - "Valencia (Radio Edit)" (single track) | that time period, which were brought to our attention "Ephemagoria" [progressive rock] Albany by fans, bands & others. The missing is listed at the end. Balcony - "Canvas" | "Blind" (single tracks) [pop rock] RECORDINGS: Saratoga Springs Hard Rock / Metal / Punk Boo Fookin' Radley (BFR) - "Freedom of Thought" (EP) Arch Fiends - "Love Is Like a Homicide" | "Prisoners" [alt pop rock] Saratoga Springs/Stony Brook (single tracks) [horror punk] Glens Falls Brad Whiting and The Cadillac Souls - "Six-Wire" | "No Blind Threat - "Everyone's a Killer" [hardcore metal] 2nd Chances" (single tracks) [blues rock] Glenmont Albany Caramel Snow - "Are You Unreal?" (EP) | "Happy Candy Ambulance - "Spray" [alt grunge rock] Saratoga Birthday (Happy New Year" to "Are You Unreal?" (single tracks) [shoegaze dreampop] Delmar Cats Don’t Have Souls - "Twenty four days of scaring the neighbors with devil music" | "Cats Don't Have Souls" David Tyo - "Oh, Life" (single) [acoustic pop] Saratoga [alt post punk prog rock] Albany Springs Che Guevara T-Shirt - "Seven Out, Pay the Don'ts" [post- Girl Blue - "Lolita" (single) [alt soul pop] Albany punk rock] Albany Great Mutations - "Live at the Tang" | "Already Dead" Kardia - "Metamorphosis" (single track) [melodic hard (single track) [psych pop baroque rock] Troy rock] Pittsfield, MA Julia Gargano -

Surrealist Manifesto Surrealist Manifesto <Written By> André

Surrealist Manifesto Surrealist Manifesto <written by> André Breton This virtual version of the Surrealist Manifesto was created in 1999. Feel free to copy this virtual document and distribute it as you wish. You may contact the transcriber at any time by writing to: [email protected]. So strong is the belief in life, in what is most fragile in life – real life, I mean – that in the end this belief is lost. Man, that inveterate dreamer, daily more discontent with his destiny, has trouble assessing the objects he has been led to use, objects that his nonchalance has brought his way, or that he has earned through his own efforts, almost always through his own efforts, for he has agreed to work, at least he has not refused to try his luck (or what he calls his luck!). At this point he feels extremely modest: he knows what women he has had, what silly affairs he has been involved in; he is unimpressed by his wealth or his poverty, in this respect he is still a newborn babe and, as for the approval of his conscience, I confess that he does very nicely without it. If he still retains a certain lucidity, all he can do is turn back toward his childhood which, however his guides and mentors may have botched it, still strikes him as somehow charming. There, the absence of any known restrictions allows him the perspective of several lives lived at once; this illusion becomes firmly rooted within him; now he is only interested in the fleeting, the extreme facility of everything. -

Record Dreams Catalog

RECORD DREAMS 50 Hallucinations and Visions of Rare and Strange Vinyl Vinyl, to: vb. A neologism that describes the process of immersing yourself in an antique playback format, often to the point of obsession - i.e. I’m going to vinyl at Utrecht, I may be gone a long time. Or: I vinyled so hard that my bank balance has gone up the wazoo. The end result of vinyling is a record collection, which is defned as a bad idea (hoarding, duplicating, upgrading) often turned into a good idea (a saleable archive). If you’re reading this, you’ve gone down the rabbit hole like the rest of us. What is record collecting? Is it a doomed yet psychologically powerful wish to recapture that frst thrill of adolescent recognition or is it a quite understandable impulse to preserve and enjoy totemic artefacts from the frst - perhaps the only - great age of a truly mass art form, a mass youth culture? Fingering a particularly juicy 45 by the Stooges, Sweet or Sylvester, you could be forgiven for answering: fuck it, let’s boogie! But, you know, you’re here and so are we so, to quote Double Dee and Steinski, what does it all mean? Are you looking for - to take a few possibles - Kate Bush picture discs, early 80s Japanese synth on the Vanity label, European Led Zeppelin 45’s (because of course they did not deign to release singles in the UK), or vastly overpriced and not so good druggy LPs from the psychedelic fatso’s stall (Rainbow Ffolly, we salute you)? Or are you just drifting, browsing, going where the mood and the vinyl takes you? That’s where Utrecht scores. -

Politics and Popular Culture: the Renaissance in Liberian Music, 1970-89

POLITICS AND POPULAR CULTURE: THE RENAISSANCE IN LIBERIAN MUSIC, 1970-89 By TIMOTHY D. NEVIN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FUFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2010 1 © 2010 Timothy Nevin 2 To all the Liberian musicians who died during the war-- (Tecumsey Roberts, Robert Toe, Morris Dorley and many others) Rest in Peace 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my parents and my uncle Frank for encouraging me to pursue graduate studies. My father’s dedication to intellectual pursuits and his life-long love of teaching have been constant inspirations to me. I would like to thank my Liberian wife, Debra Doeway for her patience in attempting to answer my thousand and one questions about Liberian social life and the time period “before the war.” I would like to thank Dr. Luise White, my dissertation advisor, for her guidance and intellectual rigor as well as Dr. Sue O’Brien for reading my manuscript and offering helpful suggestions. I would like to thank others who also read portions of my rough draft including Marissa Moorman. I would like to thank University of Florida’s Africana librarians Dan Reboussin and Peter Malanchuk for their kind assistance and instruction during my first semester of graduate school. I would like to acknowledge the many university libraries and public archives that welcomed me during my cross-country research adventure during the summer of 2007. These include, but are not limited to; Verlon Stone and the Liberian Collections Project at Indiana University, John Collins and the University of Ghana at East Legon, Northwestern University, Emory University, Brown University, New York University, the National Archives of Liberia, Dr. -

Ramifications of Surrealism in the Music of György Ligeti

JUXTAPOSING DISTANT REALITIES: RAMIFICATIONS OF SURREALISM IN THE MUSIC OF GYÖRGY LIGETI Philip Bixby TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 9, 2017 ________________________________ Charles Carson, Ph.D. Butler School of Music Supervisor ________________________________ Elliott Antokoletz, Ph.D. Butler School of Music Second Reader Abstract: Author: Philip Bixby Title: Ramifications of Surrealism in the Music of György Ligeti Supervisors: Charles Carson, Ph.D. Elliott Antokoletz, Ph.D. György Ligeti is considered by many scholars and musicians to be one of the late twentieth century’s most ingenious and influential composers. His music has been particularly difficult to classify, given the composer’s willingness to absorb a multitude of musical influences, everything from high modernism and electronic music to west-African music and Hungarian folk-song. One aesthetic influence that Ligeti acknowledged in the 1970s was Surrealism, an early twentieth-century art movement that sought to externalize the absurd juxtapositions of the unconscious mind. Despite the composer’s acknowledgement, no musicological inquiry has studied how the aesthetic goals of Surrealism have manifested in his music. This study attempts to look at Ligeti’s music (specifically the music from his third style period) through a Surrealist lens. In order to do this, I first establish key definitions of Surrealist concepts through a close reading of several foundational texts of the movement. After this, I briefly analyze two pieces of music which were associated with the beginnings of Surrealism, in order to establish the extent to which they are successfully Surreal according to my definitions. Finally, the remainder of my study focuses on specific pieces by Ligeti, analyzing how he is connected to but also expands beyond the “tradition” of musical Surrealism in the early twentieth century. -

Surrealism, Occultism and Politics

Surrealism, Occultism and Politics This volume examines the relationship between occultism and Surrealism, specif- ically exploring the reception and appropriation of occult thought, motifs, tropes and techniques by surrealist artists and writers in Europe and the Americas from the 1920s through the 1960s. Its central focus is the specific use of occultism as a site of political and social resistance, ideological contestation, subversion and revolution. Additional focus is placed on the ways occultism was implicated in surrealist dis- courses on identity, gender, sexuality, utopianism and radicalism. Dr. Tessel M. Bauduin is a Postdoctoral Research Associate and Lecturer at the Uni- versity of Amsterdam. Dr. Victoria Ferentinou is an Assistant Professor at the University of Ioannina. Dr. Daniel Zamani is an Assistant Curator at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main. Cover image: Leonora Carrington, Are you really Syrious?, 1953. Oil on three-ply. Collection of Miguel S. Escobedo. © 2017 Estate of Leonora Carrington, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2017. This page intentionally left blank Surrealism, Occultism and Politics In Search of the Marvellous Edited by Tessel M. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou and Daniel Zamani First published 2018 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2018 Taylor & Francis The right of Tessel M. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou and Daniel Zamani to be identified as the authors of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.