Hey Hipster! You Are a Hipster!”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Yorker, March 9, 2015

PRICE $7.99 MAR. 9, 2015 MARCH 9, 2015 7 GOINGS ON ABOUT TOWN 27 THE TALK OF THE TOWN Jeffrey Toobin on the cynical health-care case; ISIS in Brooklyn; Imagine Dragons; Knicks knocks; James Surowiecki on Greece. Peter Hessler 34 TRAVELS WITH MY CENSOR In Beijing for a book tour. paul Rudnick 41 TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE OF SEXUAL DIFFERENCE JOHN MCPHEE 42 FRAME OF REFERENCE What if someone hasn’t heard of Scarsdale? ERIC SCHLOSSER 46 BREAK-IN AT Y-12 How pacifists exposed a nuclear vulnerability. Saul Leiter 70 HIDDEN DEPTHS Found photographs. FICTION stephen king 76 “A DEATH” THE CRITICS A CRITIC AT LARGE KELEFA SANNEH 82 The New York hardcore scene. BOOKS KATHRYN SCHULZ 90 “H Is for Hawk.” 95 Briefly Noted ON TELEVISION emily nussbaum 96 “Fresh Off the Boat,” “Black-ish.” THE THEATRE HILTON ALS 98 “Hamilton.” THE CURRENT CINEMA ANTHONY LANE 100 “Maps to the Stars,” “ ’71.” POEMS WILL EAVES 38 “A Ship’s Whistle” Philip Levine 62 “More Than You Gave” Birgit Schössow COVER “Flatiron Icebreaker” DRAWINGS Charlie Hankin, Zachary Kanin, Liana Finck, David Sipress, J. C. Duffy, Drew Dernavich, Matthew Stiles Davis, Michael Crawford, Edward Steed, Benjamin Schwartz, Alex Gregory, Roz Chast, Bruce Eric Kaplan, Jack Ziegler, David Borchart, Barbara Smaller, Kaamran Hafeez, Paul Noth, Jason Adam Katzenstein SPOTS Guido Scarabottolo 2 THE NEW YORKER, MARCH 9, 2015 CONTRIBUTORS eric schlosser (“BREAK-IN AT Y-12,” P. 46) is the author of “Fast Food Nation” and “Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety.” jeFFrey toobin (COMMENT, P. -

Ms Girls Athletics Info

Commerce Middle School Lady Tiger Athletics Welcome to middle school athletics! We are super excited to get the year started and to get to know your daughter(s) throughout the year. Commerce ISD has issued the following statement “In order for your daughter to participate in UIL events and/or extra-curricular activities, your daughter has to follow the Hybrid model. If your daughter is strictly online, she cannot participate in any UIL event or extra curricular activities.” We will continue to have practice EVERY morning at 6:45 a.m. throughout the year. If your daughter is playing Volleyball, she will be here every morning, ready to practice at 6:45. If your daughter is in Athletics and NOT playing volleyball, she will still need to come to Athletics every morning, ready to start at 7:30 a.m. Parents will have to provide transportation to and from practice. If it is not your daughter’s assigned day to be at school, she will need to be picked up at the end of practice. Contacts: CMS: (903)-886-3795 ext. 726 Julie Brown: 8th(Basketball)/8th (Volleyball)Grade Coach- [email protected] Kayla Collum:7th(Volleyball/Track)/7th(Basketball/Track) Coach- [email protected] Tony Henry: Head Basketball Coach- [email protected] Shelley Jones: Head Volleyball/Track Coach- [email protected] Amanda Herron: Athletic Trainer- [email protected] Jeff Davidson: Athletic Director- [email protected] Coach Brown will set up a Remind for 7th and 8th Grade Girls Athletics. All information and Updated information will be found on Remind for students and parents will be on Remind. -

Momentum Contents

REPORT OF GENEROSITY & VOLUNTEERISM, 2017– 18 166 Main Street Concord, MA 01742 MOMENTUM Together Together CONTENTS 2 SPIRITING US FORWARD Momentum: A Foreword Letter of Thanks 6 FURTHERING OUR MISSION The Concord Academy Mission Gathering Momentum: A Timeline 10 DELIVERING ON PROMISES The CA Annual Fund Strength in Numbers CA’s Annual Fund at Work 16 FUELING OUR FUTURE The Centennial Campaign for Concord Academy Campaign Milestones CA Houses Financial Aid CA Labs Advancing Faculty Leadership Boundless Campus 30 BUILDING OPPORTUNITY The CA Endowment 36 VOICING OUR GRATITUDE Our Generous Donors and Volunteer Leaders C REPORT OF GENEROSITY & VOLUNTEERISM 1 Momentum It livens your step as you cross the CA campus on a crisp fall afternoon, as students dash to class, or meet on the Moriarty Athletic Campus, or run to an audition at the Performing Arts Center. It’s the feeling that comes from an unexpected discovery in CA Labs, the chorus of friendly faces in the new house common rooms, or instructors from two disciplines working together to develop and teach a new course. It is the spark of encouragement that illuminates a new path, or a lifelong pursuit — a spark that, fanned by tremendous support over these past few years, is growing into a blaze. At Concord Academy we feel that momentum every day, in the power of students, teachers, and graduates to have a positive impact on their peers and to shape their world. It’s an irresistible energy that stems from the values we embrace as an institution, driven forward by the generosity of our benefactors. -

Songs in the Key of Z: the Curious Universe of Outsider Music Free

FREE SONGS IN THE KEY OF Z: THE CURIOUS UNIVERSE OF OUTSIDER MUSIC PDF Irwin Chusid | 272 pages | 01 Apr 2000 | A Cappella Books | 9781556523724 | English | Los Angeles, CA, United States Songs in the Key of Z | Chicago Review Press If VH1's Behind the Music were as interesting as Chusid's first, and reportedly last, book, this reviewer would never leave his apartment. A record producer, music historian, and host of WFMU's Irwin Chusid. Outsider musicians can be the product of damaged DNA, alien abduction, drug fry, demonic possession, or simply sheer obliviousness. This book profiles dozens of outsider musicians, both prominent and obscure—figures such as The Shaggs, Syd Barrett, Tiny Tim, Jandek, Captain Beefheart, Daniel Johnston, Songs in the Key of Z: The Curious Universe of Outsider Music Partch, and The Legendary Stardust Cowboy—and presents their strange life stories along with photographs, interviews, cartoons, and discographies. About the only things these self-taught artists have in common are an utter lack of conventional tunefulness and an overabundance of earnestness and passion. But, believe it or not, they're worth listening to, often outmatching all contenders for inventiveness and originality. A CD featuring songs by artists profiled in the book is also available. Syd Barrett 21 Snapshots in Sound. The Shaggs 12 Eilert Pilarm. "Songs in the Key of Z" by Irwin Chusid | The Curious Universe of Outsider Music Presidents' Day. Veterans Day. Shopping Cart Checkout. Follow Us. Audio Downloads. Activity Kit. Songs in the Key of Z. Overview Reviews Author Biography Overview Outsider musicians can be the product Songs in the Key of Z: The Curious Universe of Outsider Music damaged DNA, alien abduction, drug fry, demonic possession, or simply sheer obliviousness. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

UAB-Psychiatry-Fall-081.Pdf

Fall 2008 Also Inside: Surviving Suicide Loss The Causes and Prevention of Suicide New Geriatric Psychiatry Fellowship Teaching and Learning Psychotherapy MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN Message Jamesfrom H .the Meador-Woodruff, Chairman M.D. elcome to the Fall 2008 issue of UAB Psychia- try. In this issue, we showcase some of our many departmental activities focused on patients of Wevery age, and highlight just a few of the people that sup- port them. Child and adolescent psychiatry is one of our departmental jewels, and is undergoing significant expansion. I am par- ticularly delighted to feature Dr. LaTamia White-Green in this issue, both as a mother of a child with an autism- spectrum disorder (and I thank Teddy and his grandmother both for agreeing to pose for our cover!), but also the new leader of the Civitan-Sparks Clinics. These Clinics are one of UAB’s most important venues for the assessment of children with developmental disorders, training caregivers that serve these patients, and pursuing important research outcome of many psychiatric conditions. One of our junior questions. The Sparks Clinics moved into the Department faculty members, Dr. Monsheel Sodhi, has been funded by of Psychiatry over the past few months, and I am delighted this foundation for her groundbreaking work to find ge- that we have Dr. White-Green to lead our efforts to fur- netic predictors of suicide risk. I am particularly happy to ther strengthen this important group of Clinics. As you introduce Karen Saunders, who shares how her own family will read, we are launching a new capital campaign to raise has been touched by suicide. -

Movies July & August

ENTERTAINMENT Pick your blockbuster! Who better to decide which movies are included in our inflight Language Selection entertainment programme than our passengers? Every month, you get to pick the blockbusters shown on English (EN), French (FR), German (DE), Dutch (NL), Italian (IT), Spanish (ES), Movies July & August Available in Business Class & Economy Class our long haul flights. Simply go to our Facebook page and cast your votes!facebook.com/brusselsairlines Portuguese (PT), Dutch subtitles (NL), English subtitles (EN) ˜ ACTION ˜ Oblivion Jack the Giant Slayer I Don’t Know The Hangover Part II ˜ DRAMA ˜ Hugo Mama Africa Ice Age: Dawn Ever After: PG PG R 13 13 PG NR A Good Day to Die Hard 125mins (2013) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL 114mins (2012) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL How She Does It 102 mins (2011) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL 42 120mins (2011) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL 90 mins (2011) EN, FR Of The Dinosaurs A Cinderella Story R PG PG PG PG 97 mins (2013) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL Tom Cruise, Morgan Freeman Ewan McGregor, Ian McShane 13 96 mins (2011) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL Bradley Cooper, Ed Helms 13 128 mins (2013) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL Ben Kingsley, Asa Butterfield Miriam Makeba 94 mins (2009) EN, FR, NL, DE, ES, IT 13 121 mins (1998) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT Bruce Willis, Jai Courtney Sarah Jessica Parker, Pierce Brosnan Chadwick Boseman, Harrison Ford Ray Romano, Denis Leary Drew Barrymore, Anjelica Huston JULY FROM JULY FROM FROM JULY ONLY AUGUST ONLY AUGUST AUGUST ONLY From Russia With Love Tomorrow Never Dies Percy -

Punk Aesthetics in Independent "New Folk", 1990-2008

PUNK AESTHETICS IN INDEPENDENT "NEW FOLK", 1990-2008 John Encarnacao Student No. 10388041 Master of Arts in Humanities and Social Sciences University of Technology, Sydney 2009 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Tony Mitchell for his suggestions for reading towards this thesis (particularly for pointing me towards Webb) and for his reading of, and feedback on, various drafts and nascent versions presented at conferences. Collin Chua was also very helpful during a period when Tony was on leave; thank you, Collin. Tony Mitchell and Kim Poole read the final draft of the thesis and provided some valuable and timely feedback. Cheers. Ian Collinson, Michelle Phillipov and Diana Springford each recommended readings; Zac Dadic sent some hard to find recordings to me from interstate; Andrew Khedoori offered me a show at 2SER-FM, where I learnt about some of the artists in this study, and where I had the good fortune to interview Dawn McCarthy; and Brendan Smyly and Diana Blom are valued colleagues of mine at University of Western Sydney who have consistently been up for robust discussions of research matters. Many thanks to you all. My friend Stephen Creswell’s amazing record collection has been readily available to me and has proved an invaluable resource. A hearty thanks! And most significant has been the support of my partner Zoë. Thanks and love to you for the many ways you helped to create a space where this research might take place. John Encarnacao 18 March 2009 iii Table of Contents Abstract vi I: Introduction 1 Frames -

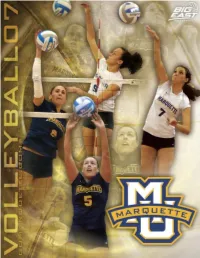

200708 Mu Vb Guide.Pdf

1 Ashlee 2 Leslie 4 Terri 5 Katie OH Fisher OH Bielski L Angst S Weidner 6 Jenn 7 Tiffany 8 Jessica 9 Kimberley 10 Katie MH Brown MH/OH Helmbrecht DS Kieser MH/OH Todd OH Vancura 11 Rabbecka 12 Julie 14 Hailey 15 Caryn OH Gonyo OH Richards DS Viola S Mastandrea Head Coach Assistant Coach Assistant Coach Pati Rolf Erica Heisser Raftyn Birath 20072007 MARQUETTE MARQUETTE VOLLEYBALL VOLLEYBALL TEAM TEAM Back row (L to R): Graydon Larson-Rolf (Manager), Erica Heisser (Assistant Coach), Kent Larson (Volunteer Assistant), Kimberley Todd. Third row: Raftyn Birath (Assistant Coach), Tiffany Helmbrecht, Rabbecka Gonyo, Katie Vancura, Jenn Brown, Peter Thomas (Manager), David Hartman (Manager). Second row: Pati Rolf (Head Coach), Ashlee Fisher, Julie Richards, Terri Angst, Leslie Bielski. Front row: Ellie Rozumalski (Athletic Trainer), Jessica Kieser, Hailey Viola, Katie Weidner, Caryn Mastandrea. L E Y B V O L A L L Table of Contents Table of Contents Quick Facts 2007 Schedule 2 General Information 2007 Roster 3 School . .Marquette University Season Preview 4 Location . .Milwaukee, Wis. Head Coach Pati Rolf 8 Enrollment . .11,000 Nickname . .Golden Eagles Assistant Coach Erica Heisser 11 Colors ...............Blue (PMS 281) and Gold (PMS 123) Assistant Coach Raftyn Birath 12 Home Arena . .Al McGuire Center (4,000) Meet The Team 13 Conference . .BIG EAST 2006 Review 38 President . .Rev. Robert A. Wild, S.J. 2006 Results and Statistics 41 Interim Athletics Dir. .Steve Cottingham Sr.Woman Admin. .Sarah Bobert 2006 Seniors 44 2006 Match by Match 47 Coaching Staff 2006 BIG EAST Recap 56 Season Preview, page 4 Head Coach . -

HIPSTERS and AMERICAN STAND-UP COMEDY By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SHAREOK repository LAUGHING FROM THE OUTSIDE: HIPSTERS AND AMERICAN STAND-UP COMEDY By CHRISTOPHER PERKINS Bachelor of Arts in English Texas State University San Marcos, Texas 2006 Master of Arts in English Texas State University San Marcos, Texas 2008 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2017 LAUGHING FROM THE OUTSIDE: HIPSTERS AND AMERICAN STAND-UP COMEDY Dissertation Approved: Dr. Elizabeth Grubgeld Dissertation Adviser Dr. Jeffrey Walker Dr. Richard Frohock Dr. Perry Gethner ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was made possible through the support of the faculty in the English department at Oklahoma State University, the careful critique of my advisory committee, and the thoughtful guidance of my advisor Dr. Elizabeth Grubgeld. I am also eternally grateful to my family for their love and support throughout the years. Finally, Dr. Jennifer Edwards has remained by my side throughout the process of composing this dissertation, and her love, patience, and criticism have played an essential role in its completion. iii Acknowledgements reflect the views of the author and are not endorsed by committee members or Oklahoma State University. Name: CHRISTOPHER PERKINS Date of Degree: MAY, 2017 Title of Study: LAUGHING FROM THE OUTSIDE: HIPSTERS AND AMERICAN STAND-UP COMEDY Major Field: ENGLISH Abstract: In recent years, stand-up comedy has enjoyed increased attention from both popular and scholarly audiences for its potential as a forum for public intellectualism. -

Shawyer Dissertation May 2008 Final Version

Copyright by Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: A Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967-1968 Committee: Jill Dolan, Supervisor Paul Bonin-Rodriguez Charlotte Canning Janet Davis Stacy Wolf Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: A Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967-1968 by Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2008 Acknowledgements There are many people I want to thank for their assistance throughout the process of this dissertation project. First, I would like to acknowledge the generous support and helpful advice of my committee members. My supervisor, Dr. Jill Dolan, was present in every stage of the process with thought-provoking questions, incredible patience, and unfailing encouragement. During my years at the University of Texas at Austin Dr. Charlotte Canning has continually provided exceptional mentorship and modeled a high standard of scholarly rigor and pedagogical generosity. Dr. Janet Davis and Dr. Stacy Wolf guided me through my earliest explorations of the Yippies and pushed me to consider the complex historical and theoretical intersections of my performance scholarship. I am grateful for the warm collegiality and insightful questions of Dr. Paul Bonin-Rodriguez. My committee’s wise guidance has pushed me to be a better scholar. -

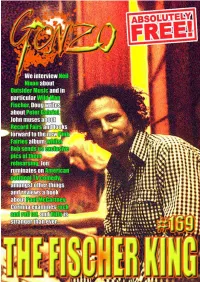

Gonzo Weekly #169

Subscribe to Gonzo Weekly http://eepurl.com/r-VTD Subscribe to Gonzo Daily http://eepurl.com/OvPez Gonzo Facebook Group https://www.facebook.com/groups/287744711294595/ Gonzo Weekly on Twitter https://twitter.com/gonzoweekly Gonzo Multimedia (UK) http://www.gonzomultimedia.co.uk/ Gonzo Multimedia (USA) http://www.gonzomultimedia.com/ 3 is euphemistically known as 'The Festive Season', and there was one week we didn't come out because British Telecom had managed to screw up our internet coverage, but apart from those, we have come out every week now for the past 169 weeks, and that truly does blow my mind somewhat when I think about it. I have always vaguely been a Dr Who fan, and although I don't think that stylistically or emotionally it has reached the heights that it did with Jon Pertwee, and even Patrick Troughton back in the day, I have followed much of the series since it came back in 2005. I lost interest half way through David Tennant's tenure in the driving seat of the TARDIS and only came back on board half way through whatshisface's seasons, but I have been massively impressed by Dear Friends, Peter Capaldi, who has brought back the curmudgeonly element that I feel has been Welcome to another issue of the magazine, which missing from the role in recent years. each issue I reiterate that I am not just proud to be the editor of, but that it never ceases to amaze me I lost interest in Dr Who for some years mainly that it has been going for so many weeks without because I had a lodger who was so irritating about a break.