B-Sides, Undercurrents and Overtones: Peripheries to Popular in Music, 1960 to the Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

É£Žé¸Ÿä¹É˜Ÿ Éÿ³æ

飞鸟ä¹é ˜Ÿ 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & 时间表) Sweetheart of the Rodeo https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/sweetheart-of-the-rodeo-928243/songs Fifth Dimension https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/fifth-dimension-223578/songs Mr. Tambourine Man https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/mr.-tambourine-man-959637/songs Younger Than Yesterday https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/younger-than-yesterday-2031535/songs Ballad of Easy Rider https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ballad-of-easy-rider-805125/songs (Untitled) https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/%28untitled%29-158575/songs Byrds https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/byrds-1018579/songs Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/dr.-byrds-%26-mr.-hyde-1253841/songs Byrdmaniax https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/byrdmaniax-1018576/songs Byrdmaniax https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/byrdmaniax-1018576/songs Farther Along https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/farther-along-1397186/songs Easy Rider https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/easy-rider-1278371/songs History of The Byrds https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/history-of-the-byrds-16843754/songs The Byrds https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-byrds-16245109/songs There Is a Season https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/there-is-a-season-7782757/songs 20 Essential Tracks from the Boxed https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/20-essential-tracks-from-the-boxed-set%3A- Set: 1965–1990 1965%E2%80%931990-38341997/songs The -

Songs About Joni

Songs About Joni Compiled by: Simon Montgomery, © 2003 Latest Update: Dec. 28, 2020 Please send comments, corrections or additions to: [email protected] © Ed Thrasher, March 1968 Song Title Musician Album / CD Title 1967 Lady Of Rohan Chuck Mitchell Unreleased 1969 Song To A Cactus Tree Graham Nash Unreleased Why, Baby Why Graham Nash Unreleased Guinnevere Crosby, Stills & Nash Crosby, Stills & Nash Pre-Road Downs Crosby, Stills & Nash Crosby, Stills & Nash Portrait Of The Lady As A Young Artist Seatrain Seatrain (Debut LP) 1970 Only Love Can Break Your Heart Neil Young After The Goldrush Our House Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young Déjà Vu 1971 Just Joni Mitchell Charles John Quarto Unreleased Better Days Graham Nash Songs For Beginners I Used To Be A King Graham Nash Songs For Beginners Simple Man Graham Nash Songs For Beginners Love Has Brought Me Around James Taylor Mudslide Slim & The Blue Horizon You Can Close Your Eyes James Taylor Mudslide Slim & The Blue Horizon 1972 New Tune James Taylor One Man Dog 1973 It's Been A Long Time Eric Andersen Stages: The Lost Album You'’ll Never Be The Same Graham Nash Wild Tales Song For Joni Dave Van Ronk songs for ageing children Sweet Joni Neil Young Unreleased Concert Recording 1975 She Lays It On The Line Ronee Blakley Welcome Mama Lion David Crosby / Graham Nash Wind On The Water 1976 I Used To Be A King David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Simple Man David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Mama Lion David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Song For Joni Denise Kaufmann Dream Flight Mellow -

The Asian Indian Classical Music Society Vishwa Mohan Bhatt

The Asian Indian Classical Music Society 52318 N Tally Ho Drive, South Bend, IN 46635 March 28 , 2013 Dear Friends, I am writing to inform you about our concerts for Spring 2013: Vishwa Mohan Bhatt (Mohan Veena or Guitar) with Subhen Chatterjee (Tabla) April 10th , 2013, Wedneday,7.00 PM, at the Hesburgh Center Auditorium Pandit Vishwa Mohan Bhatt is among the leading Indian classical instrumental musicians. He is the creator of the Mohan Veena, which has modified the Hawaiian slide guitar by adding fourteen additional strings to it, and allows him to exquisitely assimilate the techniques of the sitar, sarod and veena. He is one of the foremost disciples of Pandit Ravi Shankar. He has captivated audiences at numerous concerts in the US, Canada, Europe, the Middle East and, of course, India. Among numerous other awards, he is the recipient of the Grammy Award, 1994, with Ry Cooder, for the World Music album, A Meeting by the River. Shanmukha Priya and Hari Priya (Vocal) with M.A. Krishnaswamy (Violin) and Skandasubramanian (Mridangam), April 26th , 2013, Friday, 7.00PM, place: TBA Shanmukha Priya and Hari Priya, the renowned musical duo popularly known as the “Priya Sisters”, are among the leading exponents of the Carnatic or South Indian vocal music. After receiving their training from the renowned duo, Radha and Jayalakshmi, they are now under the guidance of Prof. T. R.Subramaniam. Since they began performing in 1989, the Priya Sisters have performed worldwide in more than two thousand concerts. Among other awards, the sisters have been the recipients of the 'Best Female Vocalists' awards from Music Academy, Sri Krishna Gana Sabha and the Indian Fine Arts Society, Chennai. -

Montana Kaimin, April 17, 1981 Associated Students of the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 4-17-1981 Montana Kaimin, April 17, 1981 Associated Students of the University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of the University of Montana, "Montana Kaimin, April 17, 1981" (1981). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 7140. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/7140 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Editors debate news philosophies By Doug O’Harra of the Society of Professional Montana Kaimin Reporter Journalists about a controversy arising out of the Weekly News’ , Two nearly opposite views of reporting of the trial and senten journalism and newspaper cing, and a Missoulian colum coverage confronted one another nist’s subsequent reply several yesterday afternoon as a Mon days later. tana newspaper editor defended On Sept. 3, Daniel Schlosser, a his paper’s coverage of the trial 36-year-old Whitefish man, was and sentencing of a man con sentenced to three consecutive 15- victed of raping young boys. year terms in the Montana State Before about 70 people, packed Prison for three counts of sexual in the University of Montana assault. -

Strange Brew√ Fresh Insights on Rock Music | Edition 03 of September 30 2006

M i c h a e l W a d d a c o r ‘ s πStrange Brew Fresh insights on rock music | Edition 03 of September 30 2006 L o n g m a y y o u r u n ! A tribute to Neil Young: still burnin‘ at 60 œ part two Forty years ago, in 1966, Neil Young made his Living with War (2006) recording debut as a 20-year-old member of the seminal, West Coast folk-rock band, Buffalo Springfield, with the release of this band’s A damningly fine protest eponymous first album. After more than 35 solo album with good melodies studio albums, The Godfather of Grunge is still on fire, raging against the System, the neocons, Rating: ÆÆÆÆ war, corruption, propaganda, censorship and the demise of human decency. Produced by Neil Young and Niko Bolas (The Volume Dealers) with co-producer L A Johnson. In this second part of an in-depth tribute to the Featured musicians: Neil Young (vocals, guitar, Canadian-born singer-songwriter, Michael harmonica and piano), Rick Bosas (bass guitar), Waddacor reviews Neil Young’s new album, Chad Cromwell (drums) and Tommy Bray explores his guitar playing, re-evaluates the (trumpet) with a choir led by Darrell Brown. overlooked classic album from 1974, On the Beach, and briefly revisits the 1990 grunge Songs: After the Garden / Living with War / The classic, Ragged Glory. This edition also lists the Restless Consumer / Shock and Awe / Families / Neil Young discography, rates his top albums Flags of Freedom / Let’s Impeach the President / and highlights a few pieces of trivia about the Lookin’ for a Leader / Roger and Out / America artist, his associates and his interests. -

Bertus in Stock 7-4-2014

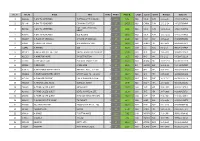

No. # Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price €. Origin Label Genre Release Eancode 1 G98139 A DAY TO REMEMBER 7-ATTACK OF THE KILLER.. 1 12in 6,72 NLD VIC.R PUN 21-6-2010 0746105057012 2 P10046 A DAY TO REMEMBER COMMON COURTESY 2 LP 24,23 NLD CAROL PUN 13-2-2014 0602537638949 FOR THOSE WHO HAVE 3 E87059 A DAY TO REMEMBER 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 14-11-2008 0746105033719 HEART 4 K78846 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 31-10-2011 0746105049413 5 M42387 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS 1 LP 20,23 NLD MOV POP 13-6-2013 8718469532964 6 L49081 A FOREST OF STARS A SHADOWPLAY FOR.. 2 LP 38,68 NLD PROPH HM. 20-7-2012 0884388405011 7 J16442 A FRAMES 333 3 LP 38,73 USA S-S ROC 3-8-2010 9991702074424 8 M41807 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVE YOU'RE ALWAYS ON MY MIND 1 LP 24,06 NLD PHD POP 10-6-2013 0616892111641 9 K81313 A HOPE FOR HOME IN ABSTRACTION 1 LP 18,53 NLD PHD HM. 5-1-2012 0803847111119 10 L77989 A LIFE ONCE LOST ECSTATIC TRANCE -LTD- 1 LP 32,47 NLD SEASO HC. 15-11-2012 0822603124316 11 P33696 A NEW LINE A NEW LINE 2 LP 29,92 EU HOMEA ELE 28-2-2014 5060195515593 12 K09100 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH AND HELL WILL.. -LP+CD- 3 LP 30,43 NLD SPV HM. 16-6-2011 0693723093819 13 M32962 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH LAY MY SOUL TO. -

DESERT ROSE BAND~ACOUSTIC (Biography)

DESERT ROSE BAND~ACOUSTIC (biography) ROCK & ROLL HALL OF FAME MEMBER CHRIS HILLMAN AND THE DESERT ROSE BAND~ACOUSTIC TO PERFORM IN A RARE APPEARANCE Joining Chris Hillman in this acoustic appearance are John Jorgenson on guitar/mandolin, Herb Pedersen on guitar and Bill Bryson on bass. Chris Hillman was one of the original members of The Byrds, which also included Roger McGuinn, David Crosby, Gene Clark and Michael Clarke. The Byrds were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1991. After his departure from the Byrds, Hillman, along with collaborator Gram Parsons, was a key figure in the development of country-rock. Hillman virtually defined the genre through his seminal work with the Byrds and later bands, The Flying Burrito Brothers and Manassas with Steven Stills. In addition to his work as a musician, Hillman is also a successful songwriter and his songs have been recorded by artists as diverse as; Emmylou Harris, Patti Smith, The Oak Ridge Boys, Beck, Steve Earl, Peter Yorn,Tom Petty, and Dwight Yoakam. In the 1980s Chris formed The Desert Rose Band which became one of country music’s most successful acts throughout the 1980s and 1990s, earning numerous ‘Top 10’ and ‘Number 1’ hits. The band’s success lead to three Country Music Association Awards, and two Grammy nominations. Although the Desert Rose Band disbanded in the early 1990s, they performed a reunion concert in 2008 and have since played a few shows together in select venues. Herb Pedersen began his career in Berkeley, California in the early 1960′s playing 5 string banjo and acoustic guitar with artists such as Jerry Garcia, The Dillards, Old and in the Way, David Grisman and David Nelson. -

Schedule Report

New Releases - 1 October 2021 SAY SOMETHING RECORDS • Available on stunning Red and Black Splatter vinyl (SSR027LP)! A collector's must!! • Featuring: Vocalist Colin Doran of Hundred Reasons, drummer Jason Bowld from Bullet For My Valentine and formerly Pitchshifter, Killing Joke • Full servicing to all relevant media • Extensive print & internet advertising • Print reviews confirmed in KERRANG! and METAL HAMMER • Featured interviews with ‘The Sappenin’ Podcast’ and ‘DJ Force X’ https://open.spotify.com/episode/0ZUhmTBIuFYlgBamhRbPHW?si=9O4x5SWmT2WbhSC0lR3P3g • For fans of: Hundred Reason, Jamie Lenman, Hell is for heroes, The Xcerts, Bullet For My Valentine, Biffy Clyro • Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TheyFellFromTheSky Twitter: https://twitter.com/tfftsband Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/tfftsband/ • Soundsphere Magazine: https://www.soundspheremag.com/news/culture/colin-doran-jason-bowld-hundred-reasons-bfmv- pitchshifter-form-rock-studio-project-they-fell-from-the-sky/ GigSoup: https://gigsoupmusic.com/pr/colin-doran-jason-bowld-form-rock-studio-project-they-fell-from-the-sky-and- release-debut-single-dry/ The AltClub: https://thealtclub.com/they-fell-from-the-sky-release-new-single-dry/ Volatile Weekly: https://volatileweekly.com/2021/03/colin-doran-jason-bowld-hundred-reasons-bfmv-pitchshifter-form-rock- studio-project-they-fell-from-the-sky-and-release-debut-single-dry/ The Punksite: https://thepunksite.com/news/they-fell-from-the-sky-announce-debut-single-and-album/ Tinnitist: https://tinnitist.com/2021/03/22/indie-roundup-23-songs-to-make-monday-far-more-enjoyable/ -

Crystal Ship 3

EDITORIAL ADDRESS: JOHN D. OWEN, 22,CONISTON WAY, BLETCHLEY, MILTON KEYNES ENGLAND MK2 5EA GILDED SPLINTERS : The generation gap in Rock. p. 4 STAR SAILORS: Philip K.Dick can build you. by Andy Muir p. 6 FEAR & LOATHING IN MIDDLE-EARTH. The Silmarillion gets the finger from Joseph Nicholas p. 9 CADENCE & CASCADE : RyCooder p.14 THE QUALITY OF MERSEY : A personal account of a Scouse New Year by Patrick Holligan p.16 ISLANDS IN THE SKY : Can SF really come true so soon? p.19 JUST A PINCH OF....: Some thoughts on spells, charms and toads , by Peter Presford p.25 ARTIST CREDITS : Yes folks, real artists! p.25 RIPPLES : Being an actual real live letter column. p.26 RECENT REEDS : The return of the book reviews. p.50 In both size and content this issue of the Crystal Ship has reached a new high: so has the printers' bill! So, finally, I've come to the stage where one of two things must happen. Either I cut back to a very small circulation and keep paying for it all myself, or I accept subscriptions for the 'zine. Until now, I haven't particularly thought the 'zine worth it,( typically modest self-depreciation!), but cir cumstances (approaching bankruptcy) force me to accept the second alter native. So from now on readers who either don't contribute, exchange or send letters of comment (even if its only "I like/loathe it") will have to pay real money, at a rate of 25p a copy in Britain or 2 per dollar over seas (bills only please). -

ARSC Journal, Fall 1989 195 Book Reviews

Book Reviews The major problem some people will have with this book involves the criteria for inclusion. But even here it is not too difficult to fault Stambler's reasoning. The major names are here, and covered well. The lesser-known artists are for the most part not included, or mentioned in other entries. However, there are some admirable examples of influential but lesser-known, bands or artists given full coverage, (e.g., The Blasters, Willy Deville, Nils Lofgren, Greg Kihn, Richard Hell and others). And some attempt has been made to include representative heavy metal, rap and punk artists, though not many appear. While it is obvious that in such an all-encompassing work there are bound to be some errors of omission, how could Stambler leave out a band such as R.E.M.? And how can there be an entry for Ian Matthews' semi-obscure band Southern Comfort, yet nothing for Richard Thompson or Fairport Convention? While the book seems to be mainly accurate and fact-filled, some errors did creep in. In the Mike Bloomfield entry, the late guitarist was credited for a solo album by his cohort Nick Gravenites; The Byrds' 1971 LP "Byrdmaniax" appears without the final letter, and at one point Nils Lofgren's pro-solo band Grin is referred to as Grim. There are no doubt a few others, but admittedly none of these errors are fatal. And though the inclusion of 110 pages of appendices in the form of Gold/Platinum Records and Grammy/Oscar winners is nice, I think most of us would prefer an index. -

Rock to Raga: the Many Lives of the Indian Guitar

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Rock to Raga: the many lives of the Indian guitar Book Section How to cite: Clayton, Martin (2001). Rock to Raga: the many lives of the Indian guitar. In: Bennett, Andy and Dawe, Kevin eds. Guitar cultures. Oxford, UK: Berg Publishers Ltd, pp. 179–208. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2001 Berg Publishers Ltd Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://www.bergpublishers.com/?tabid=1499 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Rock to Raga: The many lives of the Indian guitar Martin Clayton Chapter for “Guitar Culture”, ed. Dawe/ Bennett, Berg. 2nd DRAFT 1. Introduction What roles does the guitar play, and what meanings does it convey in India? 1 These are not easy questions to answer, since the instrument has spread into many different musical genres, in various geographical regions of the subcontinent. This chapter is nonetheless an attempt, in response to those questions, to sketch out the main features of guitar culture in India. I see it as a kind of snapshot: partial, blurred and lacking fine definition perhaps, but offering a perspective that more focused and tightly-framed studies could not. My account is based on a few weeks’ travel in India, 2 concentrating on the main metropolitan cities of Chennai, Mumbai, Calcutta and Delhi – although it also draws on the reports of many inhabitants of these cities who have migrated from other regions, particularly those rich in guitar culture such as Goa and the north-eastern states. -

Download PDF Booklet

John Kirkpatrick & Sue Harris Facing The Music 1 John Locke’s Polka/ Three Jolly Sheepskins 2 Kettle Drum 3 Trip to the Cottage/ Hunting the Squirrel/Jack Off the Green 4 A Shelter in the Time of Storm/ We Shall be Happy 5 Millfield/Saturday Night and Sunday Morn 6 Garrick’s Delight/The Flaxley Green Dance 7 Crocker’s Reel 8 Roast Beef/All Flowers in Broome 9 The Rope Waltz 10 A Cheshire Hornpipe/ Black Mary’s Hornpipe First published by Topic 1980 Produced by Tony Engle and John Kirkpatrick Recorded at Millstream Studios Engineer Nick Critchley Design by Tony Engle Notes by John Kirkpatrick Photography by Bob Naylor When we were asked to make our fourth Millfield is another tune which Chappell tells Hornpipes of this period were always in 3/2 record for Topic purely instrumental, the us was well established by the end of the 16th time. What we know as hornpipes today initial reaction of surprise quickly turned to century. Along with Saturday Night and assumed their present form and tempo later one of panic. We immediately started learning Sunday Morn and Kettle Drum, it found in the 18th century in popular stage dances. hundreds of new tunes, trying to reassess its way into John Playford’s first edition of our existing style and repertory, reexamine ‘The English Dancing Master’ in 1650. Cecil The Hereford-born actor David Garrick the motives and general philosophy behind Sharp spotted them there and reproduced (1717-79) must have been at a popular stage our music, and determine exactly where we them in his Country Dance Book (part VI) in his career when ‘The Universal Magazine’ stood now, and what new direction we were and companion Country Dance Tunes (set published Garrick’s Delight in 1751.