A Biological Survey of the Waterhouse Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Orchid Society of South Australia

NATIVE ORCHID SOCIETY of SOUTH AUSTRALIA NATIVE ORCHID SOCIETY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA JOURNAL Volume 6, No. 10, November, 1982 Registered by Australia Post Publication No. SBH 1344. Price 40c PATRON: Mr T.R.N. Lothian PRESIDENT: Mr J.T. Simmons SECRETARY: Mr E.R. Hargreaves 4 Gothic Avenue 1 Halmon Avenue STONYFELL S.A. 5066 EVERARD PARK SA 5035 Telephone 32 5070 Telephone 293 2471 297 3724 VICE-PRESIDENT: Mr G.J. Nieuwenhoven COMMITTFE: Mr R. Shooter Mr P. Barnes TREASURER: Mr R.T. Robjohns Mrs A. Howe Mr R. Markwick EDITOR: Mr G.J. Nieuwenhoven NEXT MEETING WHEN: Tuesday, 23rd November, 1982 at 8.00 p.m. WHERE St. Matthews Hail, Bridge Street, Kensington. SUBJECT: This is our final meeting for 1982 and will take the form of a Social Evening. We will be showing a few slides to start the evening. Each member is requested to bring a plate. Tea, coffee, etc. will be provided. Plant Display and Commentary as usual, and Christmas raffle. NEW MEMBERS Mr. L. Field Mr. R.N. Pederson Mr. D. Unsworth Mrs. P.A. Biddiss Would all members please return any outstanding library books at the next meeting. FIELD TRIP -- CHANGE OF DATE AND VENUE The Field Trip to Peters Creek scheduled for 27th November, 1982, and announced in the last Journal has been cancelled. The extended dry season has not been conducive to flowering of the rarer moisture- loving Microtis spp., which were to be the objective of the trip. 92 FIELD TRIP - CHANGE OF DATE AND VENUE (Continued) Instead, an alternative trip has been arranged for Saturday afternoon, 4th December, 1982, meeting in Mount Compass at 2.00 p.m. -

Survey and Description of the Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands (Freshwater) of the Temperate Lowland Plains in the South East of South Australia

Survey and description of the Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands (Freshwater) of the Temperate Lowland Plains in the South East of South Australia. C.R. Dickson, L. Farrington & M. Bachmann April 2014 Report to the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources Page i Citation Dickson C.R., Farrington L., & Bachmann M. (2014) Survey and description of the Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands (Freshwater) of the Temperate Lowland Plains in the South East of South Australia. Report to Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Government of South Australia. Nature Glenelg Trust, Mount Gambier, South Australia. Correspondence in relation to this report contact Mr Mark Bachmann Principal Ecologist Nature Glenelg Trust (08) 8797 8181 [email protected] Cover photo: Craspedia paludicola at a Seasonal Herbaceous Wetland in Bangham Conservation Park. Disclaimer This report was commissioned by the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Although all efforts were made to ensure quality, it was based on the best information available at the time and no warranty express or implied is provided for any errors or omissions, nor in the event of its use for any other purposes or by any other parties. Page ii Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge and thank the following people for their assistance during the project: . Private and public landholders throughout the South East of South Australia for providing access to their properties and sharing local knowledge of site history. Steve Clarke, Michael Dent, Claire Harding, and Abigail Goodman (DEWNR) and Bec Harmer (NGT) for providing field assistance on field surveys of wetlands between November 2013 and February 2014. -

Ramsar Sites in Order of Addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance

Ramsar sites in order of addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance RS# Country Site Name Desig’n Date 1 Australia Cobourg Peninsula 8-May-74 2 Finland Aspskär 28-May-74 3 Finland Söderskär and Långören 28-May-74 4 Finland Björkör and Lågskär 28-May-74 5 Finland Signilskär 28-May-74 6 Finland Valassaaret and Björkögrunden 28-May-74 7 Finland Krunnit 28-May-74 8 Finland Ruskis 28-May-74 9 Finland Viikki 28-May-74 10 Finland Suomujärvi - Patvinsuo 28-May-74 11 Finland Martimoaapa - Lumiaapa 28-May-74 12 Finland Koitilaiskaira 28-May-74 13 Norway Åkersvika 9-Jul-74 14 Sweden Falsterbo - Foteviken 5-Dec-74 15 Sweden Klingavälsån - Krankesjön 5-Dec-74 16 Sweden Helgeån 5-Dec-74 17 Sweden Ottenby 5-Dec-74 18 Sweden Öland, eastern coastal areas 5-Dec-74 19 Sweden Getterön 5-Dec-74 20 Sweden Store Mosse and Kävsjön 5-Dec-74 21 Sweden Gotland, east coast 5-Dec-74 22 Sweden Hornborgasjön 5-Dec-74 23 Sweden Tåkern 5-Dec-74 24 Sweden Kvismaren 5-Dec-74 25 Sweden Hjälstaviken 5-Dec-74 26 Sweden Ånnsjön 5-Dec-74 27 Sweden Gammelstadsviken 5-Dec-74 28 Sweden Persöfjärden 5-Dec-74 29 Sweden Tärnasjön 5-Dec-74 30 Sweden Tjålmejaure - Laisdalen 5-Dec-74 31 Sweden Laidaure 5-Dec-74 32 Sweden Sjaunja 5-Dec-74 33 Sweden Tavvavuoma 5-Dec-74 34 South Africa De Hoop Vlei 12-Mar-75 35 South Africa Barberspan 12-Mar-75 36 Iran, I. R. -

A Biological Survey of the Southern Mount Lofty Ranges

Southern Mount Lofty Ranges Biological Survey APPENDIX I DESCRIPTION OF ENVIRONMENTAL ASSOCIATIONS OCCURRING IN SURVEY REGION BOUNDARY. Part 1. Environmental associations in study area occurring within FLEURIEU IBRA sub-region Environmental Total % of Description Association Area vegetation (ha) remaining 3.2.1 Mt. Rapid 12,763 3.9 Hills and ridges on interbedded shale and arkose, locally overlain by tillite. Relict fans form broad flat surfaces near Cape Jervis where some coastal cliffs occur. Open parkland with sown pasture is used for livestock grazing. The scenery of the coastline is dominated by tall cliffs that vary in form and steepness, the amount of rock outcrop and vegetative cover. 3.2.2 Deep Creek 12,984 30.2 A long dissected ridge of phyllite and greywacke with cliffs, or beaches and dunes along the coastline. The cover is predominantly open parkland over sown pasture with widespread remnants of woodland and forest. Inland views tend to be middle-ground panoramic, featuring grassy ridge crests and valley floors with bracken and reed or remnant forest vegetation. 3.2.3 Fleurieu 30,389 15.6 An undulating to hilly dissected tableland on lateritized sandstone. There is a mixed cover of open parkland, forest plantation and woodland. 3.2.4 Inman 37,130 4.4 A series of low dissected ridges and spurs on tillite and arkose, with dunes and beaches or Valley cliffs along the coast. The cover is open parkland over sown pastures and cereal crops. 3.2.5 Bob Tiers 15,761 21.3 Ridges on schist and gneiss with dissected slopes and remnantsof laterite-capped tableland. -

Tracing History

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 911 Tracing History Phylogenetic, Taxonomic, and Biogeographic Research in the Colchicum Family BY ANNIKA VINNERSTEN ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2003 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Lindahlsalen, EBC, Uppsala, Friday, December 12, 2003 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Vinnersten, A. 2003. Tracing History. Phylogenetic, Taxonomic and Biogeographic Research in the Colchicum Family. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 911. 33 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-554-5814-9 This thesis concerns the history and the intrafamilial delimitations of the plant family Colchicaceae. A phylogeny of 73 taxa representing all genera of Colchicaceae, except the monotypic Kuntheria, is presented. The molecular analysis based on three plastid regions—the rps16 intron, the atpB- rbcL intergenic spacer, and the trnL-F region—reveal the intrafamilial classification to be in need of revision. The two tribes Iphigenieae and Uvularieae are demonstrated to be paraphyletic. The well-known genus Colchicum is shown to be nested within Androcymbium, Onixotis constitutes a grade between Neodregea and Wurmbea, and Gloriosa is intermixed with species of Littonia. Two new tribes are described, Burchardieae and Tripladenieae, and the two tribes Colchiceae and Uvularieae are emended, leaving four tribes in the family. At generic level new combinations are made in Wurmbea and Gloriosa in order to render them monophyletic. The genus Androcymbium is paraphyletic in relation to Colchicum and the latter genus is therefore expanded. -

Jervis Bay Territory Page 1 of 50 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region (Blank), Jervis Bay Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

BFS048 Site Species List

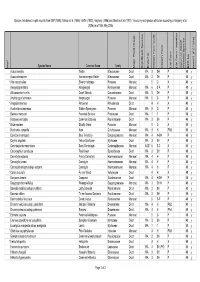

Species lists based on plot records from DEP (1996), Gibson et al. (1994), Griffin (1993), Keighery (1996) and Weston et al. (1992). Taxonomy and species attributes according to Keighery et al. (2006) as of 16th May 2005. Species Name Common Name Family Major Plant Group Significant Species Endemic Growth Form Code Growth Form Life Form Life Form - aquatics Common SSCP Wetland Species BFS No kens01 (FCT23a) Wd? Acacia sessilis Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Acacia stenoptera Narrow-winged Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Aira caryophyllea Silvery Hairgrass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Alexgeorgea nitens Alexgeorgea Restionaceae Monocot WA 6 S-R P 48 y Allocasuarina humilis Dwarf Sheoak Casuarinaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Amphipogon turbinatus Amphipogon Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y * Anagallis arvensis Pimpernel Primulaceae Dicot 4 H A 48 y Austrostipa compressa Golden Speargrass Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y Banksia menziesii Firewood Banksia Proteaceae Dicot WA 1 T P 48 y Bossiaea eriocarpa Common Bossiaea Papilionaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Briza maxima Blowfly Grass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Burchardia congesta Kara Colchicaceae Monocot WA 4 H PAB 48 y Calectasia narragara Blue Tinsel Lily Dasypogonaceae Monocot WA 4 H-SH P 48 y Calytrix angulata Yellow Starflower Myrtaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Centrolepis drummondiana Sand Centrolepis Centrolepidaceae Monocot AUST 6 S-C A 48 y Conostephium pendulum Pearlflower Epacridaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Conostylis aculeata Prickly Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis juncea Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis setigera subsp. -

Introduction Methods Results

Papers and Proceedings Royal Society ofTasmania, Volume 1999 103 THE CHARACTERISTICS AND MANAGEMENT PROBLEMS OF THE VEGETATION AND FLORA OF THE HUNTINGFIELD AREA, SOUTHERN TASMANIA by J.B. Kirkpatrick (with two tables, four text-figures and one appendix) KIRKPATRICK, J.B., 1999 (31:x): The characteristics and management problems of the vegetation and flora of the Huntingfield area, southern Tasmania. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 133(1): 103-113. ISSN 0080-4703. School of Geography and Environmental Studies, University ofTasmania, GPO Box 252-78, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001. The Huntingfield area has a varied vegetation, including substantial areas ofEucalyptus amygdalina heathy woodland, heath, buttongrass moorland and E. amygdalina shrubbyforest, with smaller areas ofwetland, grassland and E. ovata shrubbyforest. Six floristic communities are described for the area. Two hundred and one native vascular plant taxa, 26 moss species and ten liverworts are known from the area, which is particularly rich in orchids, two ofwhich are rare in Tasmania. Four other plant species are known to be rare and/or unreserved inTasmania. Sixty-four exotic plantspecies have been observed in the area, most ofwhich do not threaten the native biodiversity. However, a group offire-adapted shrubs are potentially serious invaders. Management problems in the area include the maintenance ofopen areas, weed invasion, pathogen invasion, introduced animals, fire, mechanised recreation, drainage from houses and roads, rubbish dumping and the gathering offirewood, sand and plants. Key Words: flora, forest, heath, Huntingfield, management, Tasmania, vegetation, wetland, woodland. INTRODUCTION species with the most cover in the shrub stratum (dominant species) was noted. If another species had more than half The Huntingfield Estate, approximately 400 ha of forest, the cover ofthe dominant one it was noted as a codominant. -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 Version

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/ris/key_ris_index.htm. Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 14, 3rd edition). A 4th edition of the Handbook is in preparation and will be available in 2009. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM Y Y Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (DPIPWE) GPO Box 44 HOBART Tasmania 7001 Designation date Site Reference Number Australia Ph: +61 3 6233 8011 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: July 2012 3. Country: Australia 4. Name of the Ramsar site: The precise name of the designated site in one of the three official languages (English, French or Spanish) of the Convention. -

Native Orchid Society South Australia

Journal of the Native Orchid Society of South Australia Inc Arachnorchis cardiochila Print Post Approved .Volume 31 Nº 10 PP 543662/00018 November 2007 NATIVE ORCHID SOCIETY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA POST OFFICE BOX 565 UNLEY SOUTH AUSTRALIA 5061 www.nossa.org.au. The Native Orchid Society of South Australia promotes the conservation of orchids through the preservation of natural habitat and through cultivation. Except with the documented official representation of the management committee, no person may represent the Society on any matter. All native orchids are protected in the wild; their collection without written Government permit is illegal. PRESIDENT SECRETARY Bill Dear: Cathy Houston Telephone 8296 2111 mob. 0413 659 506 telephone 8356 7356 Email: [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT Bodo Jensen COMMITTEE Bob Bates Thelma Bridle John Bartram John Peace EDITOR TREASURER David Hirst Marj Sheppard 14 Beaverdale Avenue Telephone 8344 2124 Windsor Gardens SA 5087 0419 189 188 Telephone 8261 7998 Email [email protected] LIFE MEMBERS Mr R. Hargreaves† Mr. L. Nesbitt Mr H. Goldsack† Mr G. Carne Mr R. Robjohns† Mr R Bates Mr J. Simmons† Mr R Shooter Mr D. Wells† Mr W Dear Conservation Officer: Thelma Bridle Registrar of Judges: Les Nesbitt Field Trips Coordinator: Trading Table: Judy Penney Tuber bank Coordinator: Jane Higgs ph. 8558 6247; email: [email protected] New Members Coordinator: John Bartram ph: 8331 3541; email: [email protected] PATRON Mr L. Nesbitt The Native Orchid Society of South Australia, while taking all due care, take no responsibility for loss or damage to any plants whether at shows, meetings or exhibits. -

Genetic Diversity and Adaptation in Eucalyptus Pauciflora

Genetic diversity and adaptation in Eucalyptus pauciflora Archana Gauli (M.Sc.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences, University of Tasmania June, 2014 Declarations This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of the my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Archana Gauli Date Authority of access This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Archana Gauli Date Statement regarding published work contained in thesis The publishers of the paper comprising Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 hold the copyright for that content, and access to the material should be sought from the respective journals. The remaining non-published content of the thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Archana Gauli Date i Statement of publication Chapter 2 has been published as: Gauli A, Vaillancourt RE, Steane DA, Bailey TG, Potts BM (2014) The effect of forest fragmentation and altitude on the mating system of Eucalyptus pauciflora (Myrtaceae). Australian Journal of Botany 61, 622-632. Chapter 3 has been accepted for publication as: Gauli A, Steane DA, Vaillancourt RE, Potts BM (in press) Molecular genetic diversity and population structure in Eucalyptus pauciflora subsp. -

ACT, Australian Capital Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations.