SL05 RDAC Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CYPRUS Cyprus in Your Heart

CYPRUS Cyprus in your Heart Life is the Journey That You Make It It is often said that life is not only what you are given, but what you make of it. In the beautiful Mediterranean island of Cyprus, its warm inhabitants have truly taken the motto to heart. Whether it’s an elderly man who basks under the shade of a leafy lemon tree passionately playing a game of backgammon with his best friend in the village square, or a mother who busies herself making a range of homemade delicacies for the entire family to enjoy, passion and lust for life are experienced at every turn. And when glimpsing around a hidden corner, you can always expect the unexpected. Colourful orange groves surround stunning ancient ruins, rugged cliffs embrace idyllic calm turquoise waters, and shady pine covered mountains are brought to life with clusters of stone built villages begging to be explored. Amidst the wide diversity of cultural and natural heritage is a burgeoning cosmopolitan life boasting towns where glamorous restaurants sit side by side trendy boutiques, as winding old streets dotted with quaint taverns give way to contemporary galleries or artistic cafes. Sit down to take in all the splendour and you’ll be made to feel right at home as the locals warmly entice you to join their world where every visitor is made to feel like one of their own. 2 Beachside Splendour Meets Countryside Bliss Lovers of the Mediterranean often flock to the island of Aphrodite to catch their breath in a place where time stands still amidst the beauty of nature. -

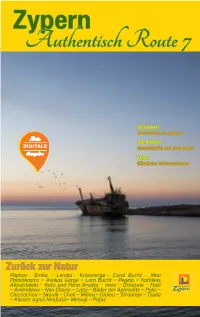

Zypern Authentisch Route 7

Zypern Authentisch Route 7 Sicherheit Autofahren in Zypern Nur Gemütliche DIGITALE Unterkünfte auf dem Land Ausgabe Tipps Nützliche Informationen Zurück zur Natur Paphos – Emba – Lemba – Kissonerga – Coral Bucht – Maa Palaiokastro – Avakas Gorge – Lara Bucht – Pegeia – Kathikas Akourdaleia – Kato und Pano Arodes – Ineia – Drouseia – Fasli – Androlikou – Neo Chorio – Latsi – Bäder der Aphrodite – Polis – Chrysochou – Skoulli – Choli – Miliou – Giolou – Stroumpi – Tsada – Kloster Agios Neofytos– Mesogi – Pafos Route 7 Paphos – Emba – Lemba – Kissonerga – Coral Bucht – Maa Palaiokastro – Avakas Gorge – Lara Bucht – Pegeia – Kathikas Akourdaleia – Kato und Pano Arodes – Ineia – Drouseia – Fasli – Androlikou – Neo Chorio – Latsi – Bäder der Aphrodite – Polis – Chrysochou – Skoulli – Choli – Miliou – Giolou – Stroumpi – Tsada – Kloster Agios Neofytos– Mesogi – Pafos Agia Marina Mazaki Islet T I L L I R I A Cape Arnaoutis Livadi (Akamas) CHRYSOCHOU BAY Gialia Ε4 Agios Georgios Islet Argaka Ryrgos tis Rigenas (Ruins) Makounta Loutra tis Marion Aphroditis (Baths Argaka of Aphrodite) Polis Kynousa Kioni Islet Neo Pelathousa Agios Chorio Stavros A Minas Agios tis Chrysochou K Isidoros Psokas Androlikou Karamoullides Lysos A Steni Goudi Peristerona M Melandra Fasli Meladeia Choli Skoulli Zacharia Agia AikaterinTirimithousa A Kios Drouseia Tera Church Filousa Kritou (15th cent) S Ineia Tera Kato Evretou Lara Sarama Akourdaleia Loukrounou Anadiou Simou Kato Arodes Pano Miliou Kannaviou Fyti Dam Gorge Pano Akourdaleia akas Drymou Lasa Kritou Av Arodes -

This Pdf of Your Paper in Cyprus: an Island Culture Belongs to the Publishers Oxbow Books and It Is Their Copyright

This pdf of your paper in Cyprus: An Island Culture belongs to the publishers Oxbow Books and it is their copyright. As author you are licenced to make up to 50 offprints from it, but beyond that you may not publish it on the World Wide Web until three years from publication (September 2015), unless the site is a limited access intranet (password protected). If you have queries about this please contact the editorial department at Oxbow Books ([email protected]). An offprint from CYPRUS An Island Culture Society and Social Relations from the Bronze Age to the Venetian Period edited by Artemis Georgiou © Oxbow Books 2012 ISBN 978-1-84217-440-1 www.oxbowbooks.com CONTENTS Preface Acknowledgements Abbreviations 1. TEXT MEETS MATERIAL IN LATE BRONZE AGE CYPRUS.......................................... 1 (Edgar Peltenburg) Settlements, Burials and Society in Ancient Cyprus 2. EXPANDING AND CHALLENGING HORIZONS IN THE CHALCOLITHIC: NEW RESULTS FROM SOUSKIOU-LAONA .................................................................... 24 (David A. Sewell) 3. THE NECROPOLIS AT KISSONERGA-AMMOUDHIA: NEW CERAMIC EVIDENCE FROM THE EARLY-MIDDLE BRONZE AGE IN WESTERN CYPRUS.......................... 38 (Lisa Graham) 4. DETECTING A SEQUENCE: STRATIGRAPHY AND CHRONOLOGY OF THE WORKSHOP COMPLEX AREA AT ERIMI-LAONIN TOU PORAKOU............................ 48 (Luca Bombardieri) 5. PYLA-KOKKINOKREMOS AND MAA-PALAEOKASTRO: A COMPARISON OF TWO NATURALLY FORTIFIED LATE CYPRIOT SETTLEMENTS ....................................... 65 (Artemis Georgiou) 6. -

Resource Stress and Subsistence Practice in Early Prehistoric Cyprus

RESOURCE STRESS AND SUBSISTENCE PRACTICE IN EARLY PREHISTORIC CYPRUS by Seth L. Button A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Art and Archaeology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Sharon C. Herbert, Chair Professor Henry T. Wright Associate Professor Nicola Terrenato Associate Professor Lauren E. Talalay © Seth L. Button 2010 For my parents, Roger and Kathy Button, my first and best teachers. ii Acknowledgments First, I wish to thank the members of my committee: Sharon Herbert, Henry Wright, Nicola Terrenato, and Lauren Talalay. The professors and curators in IPCAA, the Kelsey Museum, and the Museum of Anthropology at Michigan also furnished welcome advice and assistance. On Cyprus I had the good luck to work with Sturt Manning, Carole McCartney, Steven Falconer, Kevin Fisher, Paul Croft, and Eilis Monahan. I am also grateful to Ian Todd and Allison South for their hospitality in Kalavasos, and for sharing their intimate knowledge of the Vasilikos Valley. Stuart Swiny and Alan Simmons patiently answered questions, while Bernard Knapp and Matthew Spigelman were kind enough to share drafts of their work. Most foreign scholars who work on Cyprus for any length of time come to know the Cyprus American Archaeological Research Institute (CAARI) in Nicosia as a second home. The Director, Tom Davis, Diana Constantinides, the Librarian, and Vathoulla Moustoukki, the Executive Assistant, helped with a hundred things. My fellow graduate students in IPCAA, anthropological archaeology, and Near Eastern Studies have been my most encouraging colleagues and most honest critics: Lindsey Ambridge, Lisa Cakmak, Cat Crawford, Henry Colburn, Ryan Hughes, Tom Landvatter, Amanda Logan, Charlotte Maxwell-Jones, Adrian Ossi, Colin Quinn, Dan iii Shoup, and Adela Sobotkova. -

In the Footsteps of Paul

FMZBC In the footsteps of Paul 1st Destination: Paphos You, Saul and Barnabas have traveled 90 miles across Cyprus from Salamis to Paphos. In Paphos the Proconsul (governor) called on them so that he may hear the teachings of Jesus. The Proconsul’s attendant, Bar-Jesus or Elymas, was a false prophet and sorcerer who wished to prevent the Proconsul from hearing/believing the word. Saul, now called Paul (it is at this point the name Paul was first mentioned), blinded the false prophet like he himself had once been blinded. After witnessing this event the Proconsul now believe in the new faith of Jesus. Acts 13:6-12 6They traveled through the whole island until they came to Paphos. There they met a Jewish sorcerer and false prophet named Bar-Jesus, 7who was an attendant of the proconsul, Sergius Paulus. The proconsul, an intelligent man, sent for Barnabas and Saul because he wanted to hear the word of God. 8But Elymas the sorcerer (for that is what his name means) opposed them and tried to turn the proconsul from the faith. 9Then Saul, who was also called Paul, filled with the Holy Spirit, looked straight at Elymas and said, 10"You are a child of the devil and an enemy of everything that is right! You are full of all kinds of deceit and trickery. Will you never stop perverting the right ways of the Lord? 11Now the hand of the Lord is against you. You are going to be blind, and for a time you will be unable to see the light of the sun." Immediately mist and darkness came over him, and he groped about, seeking someone to lead him by the hand. -

Documenting Nea Paphos for Conservation and Management

The International Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume IV-2/W6, 2019 27th CIPA International Symposium “Documenting the past for a better future”, 1–5 September 2019, Ávila, Spain DOCUMENTING NEA PAPHOS FOR CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT D. Ace1, J. Marrs1, M. Santana Quintero1, L. Barazzetti2, M. Demas3, L. Friedman3, T. Roby3, M. Chamberlain4, M. Duong1, R. Awad1 1 Carleton University, Carleton Immersive Media Studio (CIMS) 1125 Colonel by Drive, Ottawa, On, K1S 5B6 Canada [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2 Politecnico di Milano, Department of Architecture, Built Environment and Construction Engineering Via Ponzio 31, 20133 Milano, Italy [email protected] 3 Getty Conservation Institute, 1200 Getty Drive, Suite 700, Los Angeles, CA 90049-1684, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 4 Department of Antiquities of Cyprus, 1 Museum Avenue, Nicosia 1097, Cyprus [email protected] Commission II , WG II/8 KEY WORDS: UNESCO World Heritage, Heritage Recording, Digital Documentation, Digital Workflow, Heritage Conservation, Management, Mapping, Archaeological Sites ABSTRACT: A cornerstone of the management and conservation of archaeological sites is recording their physical characteristics. Documenting and describing the site is an essential step that allows for delineating the components of the site and for collecting and synthesizing information and documentation (Demas, 2012). The information produced by such work assists in the decision-making process for custodians, site managers, public officials, conservators, and other related experts. Rigorous documentation may also serve a broader purpose: over time, it becomes the primary archival and monitoring record. -

A Spatial Analysis of the Bronze Age Sites of the Region of Paphos in Southwest Cyprus with the Use of Geographical Information Systems

Proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology, CAA2010 F. Contreras, M. Farjas and F.J. Melero (eds.) A Spatial Analysis of the Bronze Age Sites of the Region of Paphos in Southwest Cyprus with the Use of Geographical Information Systems Agapiou, A.1, Iacovou, M.1, Sarris, A.2 1 University of Cyprus, Archaeological Research Unit, Nicosia, Cyprus 2 Laboratory of Geophysical – Satellite Remote Sensing and Archaeo-environment, Institute for Mediterranean Studies, Foundation for Research and Technology, Hellas (IMS-FORTH), Rethymno, Crete, Greece [email protected] This paper presents the preliminary results of a spatial analysis of the Bronze Age sites of the Paphos region in Western Cyprus (3rd and 2nd millennia BC), with the use of Geographical Information Systems (GIS). In the first part of the paper, the region of Paphos is defined based on geomorphological criteria. Secondly, the known Bronze Age sites of the Paphos region, found during excavations or foot surveys, have been recorded from published reports. Spatial and chronological coordinates of the sites as well as digital geomorphological data (e.g. digital elevation model, geological maps) were synthesized in order to investigate site patterns. The authors have also considered the relation of the sites to the copper ores of Western Cyprus in order to identify transportation routes from the mines to the ports using least cost path analysis (LCP). Spatial analysis can assist in monitoring settlement patterns transformations. The analysis of the Paphos region set - tlement patterns in the Bronze Age has opened up a number of promising views concerning communication chan- nels, transportation routes and the spatial relation between copper ores and settlement hierarchy. -

Unpublished Syllabic Inscriptions of the Cyprus Museum

UNPUBLISHED SYLLABIC INSCRIPTIONS OF THE CYPRUS MUSEUM In an article which has recently appeared in Opuscula Atheniensia1 I publish twenty syllabic inscriptions of the kingdoms of Marium and Paphos, now in the custody of the Cyprus Museum either at Nicosia or in its local subsidiaries. Here I resume the task; and once more begin with Western Cyprus, to pass via the South coast round to the Central Plain. For some introductory observations on the epigraphy of these two kingdoms, I refer to that article. MARIUM No. 1. The Stele of Aristias Rectangular stele of a gritty, yellowish limestone, its corners rounded. H. 0.93; w. 0.43; th. 0.235. Its finding at the locality Ag. Georghis about a mile distant from the xo^OTtoXiç of Polis tis Chrysochou, site of the ancient Marium, and its acquisition are noted by M. Markides, the then Curator of the Cyprus Museum, in a report preserved among the papers of the Department of Antiquities (CM Files 23, 90 of 1918). The 1 Opuscula Atheniensia III, 1960, 177 ff. To Mr. A. H. S. Megaw, Director of Antiquities to the Government of Cyprus, and to Mr. P. EHkaios, Curator of the Cyprus Museum, my thanks are due for their permission to publish the syllabic documents in their custody, my apologies for long delay in availing myself of this permission. For my views on the presentation which these call for, I refer to my comments in Opuse. Ath. 1. c, 177 n. 1. In addition to the abbreviations listed in Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum IX, I here use: Bechtel for F. -

Cyprus Authentic Route 6

Cyprus Authentic Route 6 Safety Driving in Cyprus Comfort Rural Accommodation Tips Useful Information Only DIGITAL Version The Magical West Pafos • Mesogi • Agios Neophytos monastery • Tsada • Kallepeia • Letymvou • Kourdaka • Lemona • Choulou • Statos • Agios Photios • Panagia Chrysorrogiatissa Monastery • Agia Moni Monastery • Pentalia • Agia Marina • Axylou • Nata • Choletria • Stavrokonnou • Kelokedara • Salamiou • Agios Ioannis • Arminou • Filousa • Praitori • Kedares • Kidasi • Agios Georgios • Mamonia • Fasoula • Souskiou • Kouklia • Palaipaphos • Pafos Route 6 Pafos – Mesogi – Agios Neophytos monastery – Tsada – Kallepeia – Letymvou – Kourdaka – Lemona – Choulou – Statos – Agios Photios – Panagia Chrysorrogiatissa Monastery – Agia Moni Monastery – Pentalia – Agia Marina – Axylou – Nata – Choletria – Stavrokonnou – Kelokedara – Salamiou – Agios Ioannis – Arminou – Filousa – Praitori – Kedares – Kidasi – Agios Georgios – Mamonia – Fasoula – Souskiou – Kouklia – Palaipaphos – Pafos Kato Akourdaleia Kato Pano Anadiou Arodes Akourdaleia Simou Kritou Kannaviou Dam Miliou Fyti as Gorge Pano Lasa Marottou Pano vak Asprogia A Arodes Giolou Drymou Panagia Milia Kannaviou Kathikas Thrinia Pafou Theletra Chrysorrogiatissa Mamountali Agios Agia Pegeia Psathi Lapithiou Dimitrianos Moni Vretsia Fountains Akoursos Stroumpi Statos - Pegeia Polemi Koilineia Arminou Agios Agios Choulou Dam Agios Fotios Galataria Ioannis Lemona Arminou Nikolaos Mavrokolympos Agios Koili Maa Letymvou Pentalia Neofytos Monastery Faleia Kourdaka Mesana Filousa Potima -

Pafos Regional Board of Tourism

Pafos Regional Board of Tourism PAFOS INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE PafosPafos RegionalRegional BoardBoard ofof TourismTourism Bora, Sweden , Sept. 2017 Presentation by Nicolas Tsifoutis CYPRUS Pafos Region The silk factory History of Silk Road From the second century BC to the end of the fourteenth century AD, a great trade route originated from Chang'an (now Xian) in the east and ended at the Mediterranean in the west, linking China with the Roman Empire. The silk industry, developed in Pafos mainly because of the favourable climatic conditions which flourished from the time of the Byzantine Empire 5th century till the end of British rule 1960. The factory was constructed at the end of 1800 at Geroskipou municipality The factory was employing at the time more than 400 worker which was a significant number for the population of Geroskipou municipality Major producer of army parachutes for the 2nd WW and quality silk fabric for Europe Historical artifacts from Geroskipou Municipality prove that almost every family have a member working at the silk factory The entire area of the silk factory include 8 large buildings that have no use at the moment On 2014 the municipality of Geroskipou desisted to declare the silk factory as a part of the areas heritage and in cooperation with the owner of the plot have start the reformation of the factory. The silk factory will be a multiple usage area that will holt a silk museum, a gallery, an exhibition spaces, shops and a small park. The new architectural plans of the silk factory The Master plan of the project also encompass a new residential area in order to become a living and active part of the Geroskipou municipality. -

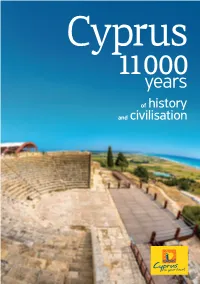

Cyprus 11000 Years of History

Contents Introduction 5 Cyprus 11000 years of history and civilisation 6 The History of Cyprus 7-17 11500 - 10500 BC Prehistoric Age 7 8200 - 1050 BC Prehistoric Age 8 1050 - 480 BC Historic Times: Geometric 9 and Archaic Periods 475 BC - 395 AD Classical, Hellenistic and Roman Periods 10 395 - 1191 AD Byzantine Period 11-12 1192 - 1489 AD Frankish Period 13 1489 - 1571 AD The Venetians in Cyprus 14 1571 - 1878 AD Cyprus becomes part of the Ottoman Empire 15 1878 - 1960 AD British rule 16 1960 - Today The Republic of Cyprus, the Turkish 17 invasion, European Union entry Lefkosia (Nicosia) 18-39 Lemesos (Limassol) 40-57 Larnaka 58-71 Pafos 72-87 Ammochostos (Famagusta) 88-95 Troodos 96-110 Aphrodite Cultural Route Map 111 Wine Route Map 112-113 Cyprus Tourism Offices 114 Cyprus Online www.visitcyprus.com Our official website provides comprehensive information on the major attractions of Cyprus, complete with maps, an updated calendar of events, a detailed hotel guide, downloadable photos and suggested itineraries. You will also find a list of tour operators covering Cyprus, information on conferences and incentives and a wealth of other useful information. Lefkosia Lemesos - Larnaka Limassol Pafos Ammochostos - Troodos 4 Famagusta Introduction Cyprus is a small country with a long history and rich culture. It is not surprising that UNESCO included the Pafos antiquities, Choirokoitia Neolithic settlement and ten of the Byzantine period churches of Troodos on its list of World Heritage Sites. The aim of this publication is to help visitors discover the cultural heritage of Cyprus. The qualified personnel at any of our Information Offices will be happy to assist you in organising your visit in the best possible way. -

Cyprus Before the Bronze Age

CYPRUS BEFORE THE BRONZE AGE ART OF THE CHALCOLITHIC PERIOD THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM MALIBU, CALIFORNIA 1990 Catalogue of an exhibition held at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, February 22-April 8, 1990; The Menil Collection, Houston, April 27-August 26, 1990. Lenders to the exhibition: Cyprus Archaeological Museums; The Menil Collection, Houston; The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu. © 1990 The J. Paul Getty Museum 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Malibu, California 90265 Mailing address: P.O. Box 2112 Santa Monica, California 90406 Christopher Hudson, Head of Publications Cynthia Newman Helms, Managing Editor Karen Schmidt, Production Manager John Harris, Editor Kurt Hauser, Designer Orlando Villagrän, Typographic Coordinator Elizabeth Burke Kahn, Production Coordinator Maps of the eastern Mediterranean and of Cyprus drawn by Beverly Lazor-Bahr Printed by Alan Lithograph Cover: Cruciform figure of limestone, said to be from Souskiou. Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum 83.AA.38 (cat. 13). Photograph : Ellen Rosenbery. Figs. 1-6, courtesy Lemba Archaeological Project. The photographs in the catalogue section are courtesy of the Cyprus Museum, Nicosia, with the exceptions of cat. 13 and the cover illustration, which are from the J. Paul Getty Museum, and cat. 29, 32, and 35, which are from the Menil Collection (photographs courtesy Hickey and Robertson, Houston). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cyprus before the Bronze age: art of the Chalcolithic period / the J. Paul Getty Museum, p. cm. ISBN 0-89236-168-9 1. Copper age—Cyprus—Exhibitions. 2. Cyprus—Antiquities—Exhibitions. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. GN778.32.C9C97 1990 939' .37—dc20 89-24543 CIP Contents Directors' Foreword 1 John Walsh and Walter Hopps Introduction 3 Vassos Karageorghis Chalcolithic Cyprus 5 Edgar J.