Chalcolithic Cyprus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTISTIC AWAKENING in ANKARA (1953)1 Bülent Ecevit

DOCUMENT ARTISTIC AWAKENING IN ANKARA (1953)1 BÜLent ecevit Until very recently, we Ankara residents were as jealous of Istanbul’s artistic awareness as we were of its sea and its trees. Our trees have yet to reach maturity, and we are as distant from the sea as ever, but an artistic awakening has now begun in Ankara as well. Concert tickets have begun to sell out in the blink of an eye, as soon as they are available. Curiously enough, tickets to the opening night of the opera reportedly sometimes sell out even before they are released.2 I say “reportedly” because this is a story I heard from one of the people interested in opening nights at the opera. Our opera no longer admits people to the concert hall who are ungroomed or who lack a formal dinner jacket. There are frequent balls at the opera. You’d think you’re in 18th-century Vienna. Because, as far as we know, this kind of dandyism no longer exists in any 20th-century city. Even in the most traditional of cities, like London, people in dinner jackets sit side- by-side with those in sports coats. 1 First published in Turkish as “Ankara’da sanat uyanıs¸ı,” Dünya, April 2, 1953, n.p. 2 The Ankara Opera, designed in 1933 by Turkish architect S¸evki Balmumcu as a space for large-scale exhibitions, was converted for use as the Ankara State Opera by German archi- tect Paul Bonatz in 1948. It was a widely recognized symbol of Turkey’s—and especially Ankara’s—cultural sophistication. -

Tula Adze Download

Australian Artefact Fact Sheet Tula adze Tula adzed dish Tula adze slug Tula adze slug Where? Across most of Australia with a focus on Central and Western Australia. The name tula or tuhla comes from the Wangkangurru people of the Simpson Desert. What? The tula adze is a hafted flaked stone tool mostly used for wood working (scraping, adzing and hardwood such as Acacias and Eucalypts. They were also used to butcher animals and to chop plants. When they are used to adze hard wood they blunt quickly and were then resharpened repeatedly by knocking off small flakes along the working edge. In archaeological sites they are usually found as exhausted slugs that have been removed from their hafting, discarded and then replaced. When? Tools such as tulas are rare in archaeological sites and especially places that can be dated. This has meant that there are small numbers that have been securely dated. The oldest dated tula adzes come from rockshelters in the Hamersley Ranges near Newman and Packsaddle dated to between 3,700 and 3,500 years ago. How? Tula adzes are made by flaking a core. They have a wide flat top (platform) that allows easy hafting and they have a curved shaped back (convex). The adzes were usually hafted into the ends of a wooden stick or spear thrower encasing the end of the stick/spear thrower in a resin glue made from spinifex or grevillea resin, kangaroo poo and sand. It took about two tulas to make a boomerang and an undecordated spear thrower would take about eight hours to make with a tula adze. -

The Bow and Arrow in the Book of Mormon

The Bow and Arrow in the Book of Mormon William J. Hamblin The distinctive characteristic of missile weapons used in combat is that a warrior throws or propels them to injure enemies at a distance.1 The great variety of missiles invented during the thousands of years of recorded warfare can be divided into four major technological categories, according to the means of propulsion. The simplest, including javelins and stones, is propelled by unaided human muscles. The second technological category — which uses mechanical devices to multiply, store, and transfer limited human energy, giving missiles greater range and power — includes bows and slings. Beginning in China in the late twelfth century and reaching Western Europe by the fourteenth century, the development of gunpowder as a missile propellant created the third category. In the twentieth century, liquid fuels and engines have led to the development of aircraft and modern ballistic missiles, the fourth category. Before gunpowder weapons, all missiles had fundamental limitations on range and effectiveness due to the lack of energy sources other than human muscles and simple mechanical power. The Book of Mormon mentions only early forms of pregunpowder missile weapons. The major military advantage of missile weapons is that they allow a soldier to injure his enemy from a distance, thereby leaving the soldier relatively safe from counterattacks with melee weapons. But missile weapons also have some signicant disadvantages. First, a missile weapon can be used only once: when a javelin or arrow has been cast, it generally cannot be used again. (Of course, a soldier may carry more than one javelin or arrow.) Second, control over a missile weapon tends to be limited; once a soldier casts a missile, he has no further control over the direction it will take. -

CILICIA: the FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES in ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson

CILICIA: THE FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES IN ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson Summary This article explores the origin of the Christian church in Anatolia. While individual believers undoubtedly entered Anatolia during the 30s after the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:9–10), the book of Acts suggests that it was not until the following decade that the first church was organized. For it was at Antioch, the capital of the Roman province of Syria, that the first Christians appeared (Acts 11:20–26). Yet two obscure references in Acts point to the organization of churches in Cilicia at an earlier date. Among the addressees of the letter drafted by the Jerusalem council were the churches in Cilicia (Acts 15:23). Later Paul visited these same churches at the beginning of his second ministry journey (Acts 15:41). Paul’s relationship to these churches points to this apostle as their founder. Since his home was the Cilician city of Tarsus, to which he returned after his conversion (Gal. 1:21; Acts 9:30), Paul was apparently active in church planting during his so-called ‘silent years’. The core of these churches undoubtedly consisted of Diaspora Jews who, like Paul’s family, lived in the region. Jews from Cilicia were members of a Synagogue of the Freedmen in Jerusalem, to which Paul was associated during his time in Jerusalem (Acts 6:9). Antiochus IV (175–164 BC) hellenized and urbanized Cilicia during his reign; the Romans around 39 BC added Cilicia Pedias to the province of Syria. Four cities along with Tarsus, located along or near the Pilgrim Road that transects Anatolia, constitute the most likely sites for the Cilician churches. -

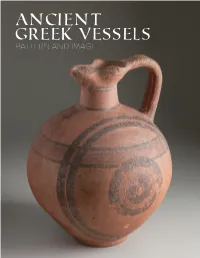

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

Ankara University

Ankara University FOLLOW-UP EVALUATION REPORT July 2011 Team: Fuada Stankovic, chair Alina Gavra Andy Gibbs, coordinator Institutional Evaluation Programme/Ankara University/July 2011 Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Institutional Evaluation Programme and follow-up evaluation process ............................ 3 1.2 Ankara University and the national context ..................................................................... 4 1.3 The Self Evaluation Process ............................................................................................. 4 1.4. Description of the University ............................................................................................ 5 1.5. Changes that have been made since the original evaluation ............................................ 5 2. Internationalisation ......................................................................................................... 7 3. Science and society ....................................................................................................... 10 4. University / Industry Collaboration ................................................................................ 12 5. Quality Monitoring and Administration ......................................................................... 14 6. Conclusion ..................................................................................................................... 16 2 Institutional -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Neolithic and chalcolithic cultures in Turkish Thrace Erdogu, Burcin How to cite: Erdogu, Burcin (2001) Neolithic and chalcolithic cultures in Turkish Thrace, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3994/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk NEOLITHIC AND CHALCOLITHIC CULTURES IN TURKISH THRACE Burcin Erdogu Thesis Submitted for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. University of Durham Department of Archaeology 2001 Burcin Erdogu PhD Thesis NeoHthic and ChalcoHthic Cultures in Turkish Thrace ABSTRACT The subject of this thesis are the NeoHthic and ChalcoHthic cultures in Turkish Thrace. Turkish Thrace acts as a land bridge between the Balkans and Anatolia. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

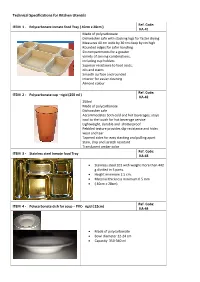

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils Ref. Code: ITEM 1 - Polycarbonate inmate food Tray ( 40cm x 28cm ) KA-41 Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe with stacking lugs for faster drying Measures 40 cm wide by 30 cm deep by cm high Rounded edges for safer handling Six compartments for a greater variety of serving combinations, including cup holders Superior resistance to food acids, oils and stains Smooth surface and rounded interior for easier cleaning Almond colour Ref. Code: ITEM 2 - Polycarbonate cup –rigid (250 ml ) KA-42 250ml Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe Accommodates both cold and hot beverages; stays cool to the touch for hot beverage service Lightweight, durable and shatterproof Pebbled texture provides slip-resistance and hides wear and tear Tapered sides for easy stacking and pulling apart Stain, chip and scratch resistant Translucent amber color Ref. Code: ITEM 3 - Stainless steel Inmate food Tray KA-43 • Stainless steel 201 with weight more than 442 g divided in 5 parts. • Height minimum 2.5 cm. • Material thickness minimum 0.5 mm • ( 40cm x 28cm) Ref. Code: ITEM 4 - Polycarbonate dish for soup – PVC- rigid ( 22cm) KA-44 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 350-360 ml Ref. Code: ITEM 5 - Plastic dish for salad – PVC- rigid KA-45 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 225-250 ml ITEM 6- Heavy Duty Frying-pan from ( 2 set of 6 pcs from the biggest until Ref. Code: the smallest size) KA-46 Set of 6 Pcs from the biggest until the smallest size) Size fir the biggest one : 30-035 x 15-19.0-15 x 2.5 6.0 • Weight: 0.6-1.5 kg • Material: stainless steel Ref. -

The Political Status of the Romani Language in Europe. Mercator Working Papers

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 479 303 FL 027 781 AUTHOR Bakker, Peter; Rooker, Marcia TITLE The Political Status of the Romani Language in Europe. Mercator Working Papers. SPONS AGENCY European Union, Brussels (Belgium). REPORT NO WP-3 ISSN ISSN-1133-3928 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 37p.; Produced by CIEMEN (Escarre International Centre for Ethnic Minorities and Nations), Barcelona, Spain. Contains small print. AVAILABLE FROM CIEMEN, Rocafort 242, bis, 08020 Barcelona,(Catalunya), Spain. Tel: 34-93-444-38-00; Fax: 34-93-444-38-09; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.ciemen.org/mercator. For full text: http://www.ciemen.org/mercator/ pdf/wp3-def-ang.PDF. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Civil Rights; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Language Usage; Language of Instruction; *Minority Groups;,Public Policy; *Regional Dialects; Sociolinguistics IDENTIFIERS European Union; *Gypsies; Roma ABSTRACT This paper examines the political status of Romani. the language of the Gypsies/Roma, in the European Union (EU). Even though some groups do not call themselves "Roma," all Romani speaking groups use the name "Romanes" for their language and "Romani/Romano/Romane" for everything related to their group. All groups use the same language, and all languages can be subdivided into dialects. Three aspects make Romani dialects more diverse than other EU dialects: absence of centuries long influence from a standard language or prestige dialect; influence from a variety of local languages; and a great number of communities of Romani speakers (with speakers not all in contact with each other). -

293 Radiocarbon and Stable

RADIOCARBON, Vol 46, Nr 1, 2004, p 293–300 © 2004 by the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona RADIOCARBON AND STABLE ISOTOPE EVIDENCE OF DIETARY CHANGE FROM THE MESOLITHIC TO THE MIDDLE AGES IN THE IRON GATES: NEW RESULTS FROM LEPENSKI VIR C Bonsall1,2 • G T Cook3 • R E M Hedges4 • T F G Higham4 • C Pickard1 • I RadovanoviÊ5 ABSTRACT. A previous radiocarbon dating and stable isotope study of directly associated ungulate and human bone samples from Late Mesolithic burials at Schela Cladovei in Romania established that there is a freshwater reservoir effect of approximately 500 yr in the Iron Gates reach of the Danube River valley in southeast Europe. Using the δ15N values as an indicator of the percentage of freshwater protein in the human diet, the 14C data for 24 skeletons from the site of Lepenski Vir were corrected for this reservoir effect. The results of the paired 14C and stable isotope measurements provide evidence of substantial dietary change over the period from about 9000 BP to about 300 BP. The data from the Early Mesolithic to the Chalcolithic are consistent with a 2-component dietary system, where the linear plot of isotopic values reflects mixing between the 2 end-members to differing degrees. Typically, the individuals of Mesolithic age have much heavier δ15N signals and slightly heavier δ13C, while individuals of Early Neolithic and Chalcolithic age have lighter δ15N and δ13C values. Contrary to our earlier suggestion, there is no evidence of a substantial population that had a transitional diet midway between those that were characteristic of the Mesolithic and Neolithic. -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs.