Ethnic Mexicans and the Left In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Composing a Chican@ Rhetorical Tradition: Pleito Rhetorics and the Decolonial Uses of Technologies for Self-Determination Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/52c322dm Author Serna, Elias Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Composing a Chican@ Rhetorical Tradition: Pleito Rhetorics and the Decolonial Uses of Technologies for Self-Determination A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Elias Serna June 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Vorris L. Nunley, Chairperson Dr. Keith Harris Dr. Dylan E. Rodriguez Dr. James Tobias Copyright by Elias Serna 2017 The Dissertation of Elias Serna is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my chair Dr. Vorris Nunley for the mentorship, inspiration and guidance navigating the seas of rhetoric and getting through this project. I would also like to thank Dr. Tiffany Ann Lopez for her work getting me started on the path to doctoral studies. An excellent group of professors instructed and inspired me along the way including Dylan Rodriguez, James Tobias, Keith Harris, Jennifer Doyle, Susan Zieger, Devra Weber, Juan Felipe Herrera and many others. The English department advisors were loving and indispensable, especially Tina Feldman, Linda Nellany and Perla Fabelo. Rhetoric, English and Ethnic Studies scholars from off campus including Damian Baca, Jaime Armin Mejia, Rudy Acuña, Juan Gomez- Quiñonez, Irene Vasquez, Martha Gonzales, Anna Sandoval, George Lipsitz, Cristina Devereaux Ramirez, Laura Perez, Reynaldo Macias, Aja Martinez, Iriz Ruiz, Cruz Medina and many others inspired me through their scholarship, friendship and consejo. -

Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Master's

Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Global Studies Jerónimo Arellano, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Sarah Mabry August 2018 Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Copyright by Sarah Mabry © 2018 Dedication Here I acknowledge those individuals by name and those remaining anonymous that have encouraged and inspired me on this journey. First, I would like to dedicate this to my great grandfather, Jerome Head, a surgeon, published author, and painter. Although we never had the opportunity to meet on this earth, you passed along your works of literature and art. Gleaned from your manuscript entitled A Search for Solomon, ¨As is so often the way with quests, whether they be for fish or buried cities or mountain peaks or even for money or any other goal that one sets himself in life, the rewards are usually incidental to the journeying rather than in the end itself…I have come to enjoy the journeying.” I consider this project as a quest of discovery, rediscovery, and delightful unexpected turns. I would like mention one of Jerome’s six sons, my grandfather, Charles Rollin Head, a farmer by trade and an intellectual at heart. I remember your Chevy pickup truck filled with farm supplies rattling under the backseat and a tape cassette playing Mozart’s piano sonata No. 16. This old vehicle metaphorically carried a hard work ethic together with an artistic sensibility. -

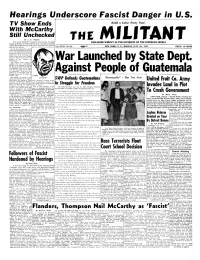

Fascist Danger in U.S

Hearings Underscore Fascist Danger in U.S. ------------------------------------------- ® --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- TV Show Ends Build a Labor Party Now! With McCarthy Still Unchecked By L. P. Wheeler The Army-McCarthy hearings closed June 17 after piling up 36 days of solid evidence that a fascist movement called McCarthyism has sunk roots deep into the govern ment and the military. For 36 days McCarthy paraded before some 20,000,000 TV viewers as the self-appointed custodian of America’s security. No one chal lenged him when he turned the Senate caucus room into a fascist forum to lecture with charts and pointer on the “menace of Communism.” War Launched by State Dept. This ghastly farce seems in credible. Yet the “anti-<McCar- thyites’’ in the hearing sat before the Wisconsin Senator and nodded in agreement while he hit them over the head with the “menace of Communism.” And then they blinked as if astonished when he Against People of Guatemala brought down his “21 years of treason” club. The charge of treason is the M cCa r t h y “Eventually” - But Not Now ready-made formula of the Amer SWP Defends Guatemalans ican fascists for putting a “save many unionists, minority people United Fruit Co. -

Siete Lenguas: the Rhetorical History of Dolores Huerta and the Rise of Chicana Rhetoric Christine Beagle

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository English Language and Literature ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2016 Siete Lenguas: The Rhetorical History of Dolores Huerta and the Rise of Chicana Rhetoric Christine Beagle Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds Recommended Citation Beagle, Christine. "Siete Lenguas: The Rhetorical History of Dolores Huerta and the Rise of Chicana Rhetoric." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds/34 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Language and Literature ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Garcia i Christine Beagle Candidate English, Rhetoric and Writing Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Michelle Hall Kells, Chairperson Irene Vasquez Natasha Jones Melina Vizcaino-Aleman Garcia ii SIETE LENGUAS: THE RHETORICAL HISTORY OF DOLORES HUERTA AND THE RISE OF CHICANA RHETORIC by CHRISTINE BEAGLE B.A., English Language and Literature, Angelo State University, 2005 M.A., English Language and Literature, Angelo State University, 2008 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ENGLISH The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico November 10, 2015 Garcia iii DEDICATION To my children Brandon, Aliyah, and Eric. Your brave and resilient love is my savior. I love you all. Garcia iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, to my dissertation committee Michelle Hall Kells, Irene Vasquez, Natasha Jones, and Melina Vizcaino-Aleman for the inspiration and guidance in helping this dissertation project come to fruition. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Fanning the Flames of Discontent: the Free Speech Fight of The

FANNING THE FLAMES OF DISCONTENT: THE FREE SPEECH FIGHT OF THE KANSAS CITY INDUSTRIAL WORKERS OF THE WORLD AND THE MAKING OF MIDWESTERN RADICALISM A THESIS IN History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by KEVIN RANDALL BAILEY B.S., University of Central Missouri, 2013 Kansas City, Missouri 2016 FANNING THE FLAMES OF DISCONTENT: THE FREE SPEECH FIGHT OF THE KANSAS CITY INDUSTRIAL WORKERS OF THE WORLD AND THE MAKING OF MIDWESTERN RADICALISM Kevin Randall Bailey Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2016 ABSTRACT This project deals with the free speech fight of 1911 that occurred in Kansas City and was organized and led by the Industrial Workers of the World. The free speech fight serves as a case study in localized Midwestern radicalism, specifically its unique manifestation in Kansas City. While many scholars of labor radicalism have focused on the larger metropolitan areas such as Chicago, New York City, and Detroit, this study departs from that approach by examining how labor radicalism took root and developed outside of the metropolitan centers. The Industrial Workers of the World, one of the most radical unions in American history, provides an excellent example of an organization that situated itself outside of the traditional spheres of labor organization through its intense focus on recruiting and radicalizing large segments of the unskilled and marginalized workforce throughout the country. iii In the Midwest, particularly in Kansas City, this focus evolved into a growing recognition that in order to be a stable, combative, and growing union in the Midwest, traditional notions of only recruiting white skilled workers employed in industry would not work. -

Centro Cultural De La Raza Archives CEMA 12

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3j49q99g Online items available Guide to the Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives CEMA 12 Finding aid prepared by Project director Sal Güereña, principle processor Michelle Wilder, assistant processors Susana Castillo and Alexander Hauschild June, 2006. Collection was processed with support from the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States (UC MEXUS). Updated 2011 by Callie Bowdish and Clarence M. Chan University of California, Santa Barbara, Davidson Library, Department of Special Collections, California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives Santa Barbara, California, 93106-9010 (805) 893-8563 [email protected] © 2006 Guide to the Centro Cultural de la CEMA 12 1 Raza Archives CEMA 12 Title: Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives Identifier/Call Number: CEMA 12 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Barbara, Davidson Library, Department of Special Collections, California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 83.0 linear feet(153 document boxes, 5 oversize boxes, 13 slide albums, 229 posters, and 975 online items)Online items available Date (inclusive): 1970-1999 Abstract: Slides and other materials relating to the San Diego artists' collective, co-founded in 1970 by Chicano poet Alurista and artist Victor Ochoa. Known as a center of indigenismo (indigenism) during the Aztlán phase of Chicano art in the early 1970s. (CEMA 12). Physical location: All processed material is located in Del Norte and any uncataloged material (silk screens) is stored in map drawers in CEMA. General Physical Description note: (153 document boxes and 5 oversize boxes).Online items available creator: Centro Cultural de la Raza http://content.cdlib.org/search?style=oac-img&sort=title&relation=ark:/13030/kt3j49q99g Access Restrictions None. -

Phililp Taft Papers

THE PHILIP TAFT COLLECTION Papers, 1955-1972 (Predominantly, 1960-62, 1972) 2 linear feet Accession Number 495 L. C. Number MS The Philip Taft papers were donated by Theresa Taft, and placed in the Archives between 1971 and 1979. They were opened to researchers in January, 1985. Dr. Philip Taft was born in 1902, in Syracuse, New York. At the age of 14 he left New York and spent the next eight years working at odd jobs in factories, Great Lakes ore boats, the Midwest grain harvest, Northwest logging camps and the railroad. It was during this period, in 1917, that he joined the Industrial Workers of the World. He later worked with the IWW Organization Committee, an executive group for the agricultural workers. He returned to New York and finished High School at the age of 26. He was then accepted at the University of Wisconsin, where he worked with Selig Perlman, a prominent labor historian. He co-authored The History of Labor in the U.S. 1896-1932 with Dr. Perlman while still a graduate student, and went on to write numerous books on economics and labor history. Among these was an in-depth, two volume history of the American Federation of Labor. He received his doctorate in economics in 1935 and subsequently worked for the Wisconsin Industrial Commission, the Resettlement Administration and the Social Security Administration. In 1937, he joined the economics department faculty at Brown University and served as department chairman from 1949-1953. Dr. Taft was on of the founding editors of the Labor History journal in 1959, and served on the editorial board until 1976. -

Ecobiz April

ECO-BIZ Inside this issue…….. Businessman with a difference VOLUME I ISSUE 1 Business Crossword Early Bird Prize News u can use Top stories….. Top ranking business schools We welcome you all to the first edition of ECO-BIZ the economics-commerce-accounts-essential info zone. Through this publication our aim is to make you all experience the power of knowledge, the power of economy and fi- nance, the power of media and advertising, the power of brands and logos, the power of industrialists….. We are proud and happy to present the first issue and hope you will enjoy reading it. We have come up with some innova- tive ideas of presenting information which we hope will make reading enjoyable. You will love the thrill it gives, cheer it creates, storm that will surround you, beat in the heart, the victory, the defeat of men….machine etc. The last decade or so has seen a proliferation of brands like never before, paralleled by a furious upsurge in advertising activity. A million messages inundate the consumer urging him to buy bigger, better and more products. In this stimulating issue the readers will be faced with new challenges in the form of questions, made aware of economic news that will rack their brains and encourage them to keep themselves abreast of all the latest in the field of branding, ad- vertising and marketing. Update your business knowledge and see how you score in the quiz given in the newsletter and allow us the opportunity of introducing you to a world which hitherto might have seemed not so interesting……. -

Jerome Deportation and the Role of Mexican Miners Goals: to Focus On

Jerome Deportation and the Role of Mexican Miners Goals: To focus on the Progressive Era and its effects in Arizona specifically related to mining, immigration, and labor unions. Objectives: Students will be able to analyze primary source documents, identify causes of labor unions, and evaluate union influence among Mexican miners in Jerome, Arizona. Grade level: 712 Materials: Computer lab Document Analysis Worksheets Peer Evaluation rubric Background readings and textbooks Drawing paper Colored pencils, markers Procedures: Present background information to the class: Review the impact of World War I and the changes it brought to the American economy. Also review with students the Russian Revolution and the rise of union's world wide. "By May of 1917 all of the twenty or so mines in Jerome were affected by strikes. The strikes that led to the deportation were complicated by the rivalry between the IWW and the AFL’s Mine Mill and Smelter Workers (MMSW). The power struggle between them left the workingclass community in the district bitterly divided. A third labor union, the Liga Protectura [sic], Latina representing about 500 Mexican miners, complicated the mix with their own demands." From : http://www.azjerome.com/pages/jerome/wobblies.htm The following activities may be modified depending on a particular grade level or class accommodations. Activity 1: Background and Circumstances 1. Read: http://www.azjerome.com/pages/jerome/wobblies.htm 2. Use the preceding reading and textbook to answer the following Vocabulary Industrial Revolution Strike Union IWW / Industrial Workers of the World Metal Mine Workers Industrial Union Knights of Labor United Verde Copper Company Identify Eugene Jerome La Liga Protectora Latina Wobblies AFL Mine Mill and Smelter Workers Jerome deportation Questions Why did World War I create a demand for copper? As copper demand increased, what did the miner's want in return? Activity 2: Primary Source photograph Study the following photograph from Cline Library Colorado Plateau Digital Archives and use the readings from above. -

The Cornerstone Eagle

THE CORNERSTONE EAGLE July 2016 Edition Cornerstone International Group’s MISSION is to be the best executive recruiting group worldwide, but our VISION is to be a true mentor and coach, one-on-one, with our clients, candidates and partners locally. We believe the way to do it is to promote our 3C VALUES of Community, Credibility, and Continuity. We succeed when our partners have achieved Healthier Businesses and Lives. The Cornerstone Eagle is not a sales letter to promote activities of our 70 offices globally, but a 3C tool to inspire you to maximize your personal and professional potential to be a Better Leader and a Better Person both at home and at business. We shall be your Faithful Companion / Coach / Mentor on your life and career journey, supporting you to discover yourself and offering good advice regarding the SIX important aspects of your professional Life: Identity, Money, Career Options, Health, Relationships and Your Future (spiritual and your legacy reminders). In this issue, we pause and consider the REAL meaning of riches, wealth and treasures. They all seem at first to carry monetary value. However, they also possess the non-monetary aspect of cost and burdens in your life. We pray that these powerful wings of the Eagle shall continue to enable you to soar to new heights. Best Wishes, Simon Wan Chief Executive Cornerstone International Group Phone No.: +86 21 6474 7064 |: [email protected] WHERE IS YOUR TREASURE? Treasure is what you deem to be valuable and what your heart & mind yearns for constantly. This could be your pursuit of money and wealth; maybe it is power and the desire to be recognized as a leader; maybe it is looking spiritual on the outside so that people think you have it together. -

Mining Wars: Corporate Expansion and Labor Violence in the Western Desert, 1876-1920

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 2009 Mining wars: Corporate expansion and labor violence in the Western desert, 1876-1920 Kenneth Dale Underwood University of Nevada Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Latin American History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Underwood, Kenneth Dale, "Mining wars: Corporate expansion and labor violence in the Western desert, 1876-1920" (2009). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 106. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1377091 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MINING WARS: CORPORATE EXPANSION AND LABOR VIOLENCE IN THE WESTERN DESERT, 1876-1920 by Kenneth Dale Underwood Bachelor of Arts University of Southern California 1992 Master