EQMI ACLU Request for Interpretative Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

Domestic Violence in TLGBIQ Communities

Resources What is domestic violence ? SafeHouse Services are all free, confidential, and inclusive. We provide: Domestic or relationship violence is a pattern of behavior where one person 24 Hour Help Line: 734-995-5444 tries to control any other person who is Help getting a protection order Legal advocacy Domestic close to them using tactics of power Counseling and control. It can include physical, Safety Planning Violence in emotional, sexual, spiritual and/or Support Groups Shelter economic abuse. TLGBIQ Local Resources: Domestic violence is a gendered crime Jim Toy Community Center : 734- Communities and is rooted in patriarchy. We 995-9867 http://www.wrap- recognize that domestic violence is up.org/ mostly committed by men against The Neutral Zone (734) 214- women. However, SafeHouse Center also 9995 http://www.neutral- realizes that sexual assault does occur zone.org/ against all genders and across all Parents Families & Friends of A Resource for sexual orientations. That being said, we Lesbians & Gays (PFLAG) Ann do work to end the oppression of all Arbor 734-741-0659 Transgender, Lesbian, people as well as value and celebrates http://www.pflagaa.org/ the diversity of our community. Pride Zone at Ozone Center Bisexual, Gay, Intersex, SafeHouse Center also strives to protect (734)662-2265 Queer/Questioning the rights of everyone. http://ozonehouse.org/programs SafeHouse Center /queerzone.php Survivors of Domestic Spectrum Center 734-763-4186 http://spectrumcenter.umich.edu Violence How can I h elp my friend or (U of -

LGBT Detroit Records

476430 Do Not Detach Hotter Than July SUNDAY BRUNCH Sunday, July 28 1:00 pm Roberts Riverwalk Detroit Hotel 1000 River Place Dr Detroit, Ml 48207 Admit One 476430 LQL8QZ Do Not Detach Hotter Than July SUNDAY BRUNCH Hosted by Billionaire Boys Club Sunday, July 29 1:00 pm The Detroit Yacht Club 1 Riverbank Rd Belie Isle | Detroit Admit One Z. Q £ 8 Q Z City of Detroit CITY CLERK'S OFFICE Your petition No. 140 to the City Council relative to Detroit Black Gay Pride, Inc., for "Detroit’s Hotter Than July. 2002" July 25-28, 20Q_2_at Palmer Park; also Candlelight Spiritual/March, July 25, 2002. was considered by that body and GRANTED in accordance with action adopted_____ 3/20/02 —__ J.C.C. page. Permit Honorable City Gour’iCTT— To your Committee of the Whole was referred petition of Detroit Black Gay JACKIE L. CURRIE Pride, Inc. (#140) for “Detroit’s Hotter City Clerk. Than July! 2002” at Palmer Park. After consultation with the concerned depart ments and careful consideration of the request, your Committee recommends that same be granted in accordance with m the following resolution. Respectfully submitted, SHEILA COCKREL Chairperson By Council Member S. Cockrel: Resolved, That subject to the approval of the Consumer Affairs, Health, Police, Recreation and Transportation Depart ments, permission be and is hereby grant- ced to Detroit Black Gay Pride, Inc. (#140) i6r “Defroify Rotf&r Than July! 2002”, July 25-28, 2002 at Palmer Park; also, Candlelight Spiritual Vigil/March, July 25, 2002, commencing at Woodward, pro ceeding in the area of McNichols and Merrill Plaissance, ending at Palmer Park. -

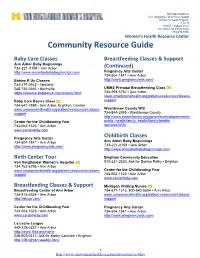

Community Resource Guide

Michigan Medicine Von Voigtlander Women’s Hospital Women’s Health Program Floor 9 1540 E. Hospital Drive Ann Arbor, MI 48109-4276 734-936-8886 Women’s Health Resource Center Community Resource Guide Baby Care Classes Breastfeeding Classes & Support Ann Arbor Baby Beginnings 734-221-0158 ▪ Ann Arbor (Continued) http://www.annarborbabybeginnings.com/ Pregnancy Arts Center 734-604-1841 ▪ Ann Arbor Babies R Us Classes http://www.pregnancyarts.com/ 734-477-0943 ▪ Ypsilanti 248-735-0365 ▪ Northville UMHS Prenatal Breastfeeding Class https://reserve.babiesrus.com/events.html\ 734-998-5782 ▪ Ann Arbor www.umwomenshealth.org/patient-resources/classes- Baby Care Basics Class support 734-647-7888 ▪ Ann Arbor, Brighton, Canton www.umwomenshealth.org/patient-resources/classes- Washtenaw County WIC support 734-544-2995 ▪ Washtenaw County http://www.ewashtenaw.org/government/departments/ Center for the Childbearing Year public_health/family_health/family-health- 734-663-1523 ▪ Ann Arbor services/WIC/ www.center4cby.com Pregnancy Arts Center Childbirth Classes 734-604-1841 ▪ Ann Arbor Ann Arbor Baby Beginnings http://www.pregnancyarts.com/ 734-221-0158 ▪ Ann Arbor http://www.annarborbabybeginnings.com/ Birth Center Tour Brighton Community Education Von Voigtlander Women’s Hospital 810-231-2820, Ask for Denise Pelky ▪ Brighton 734-763-6295 ▪ Ann Arbor www.umwomenshealth.org/patient-resources/classes- Center for the Childbearing Year support 734-663-1523 ▪ Ann Arbor www.center4cby.com Breastfeeding Classes & Support Michigan Visiting Nurses Breastfeeding -

Organizations Endorsing the Equality Act

647 ORGANIZATIONS ENDORSING THE EQUALITY ACT National Organizations 9to5, National Association of Working Women Asian Americans Advancing Justice | AAJC A Better Balance Asian American Federation A. Philip Randolph Institute Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance (APALA) ACRIA Association of Flight Attendants – CWA ADAP Advocacy Association Association of Title IX Administrators - ATIXA Advocates for Youth Association of Welcoming and Affirming Baptists AFGE Athlete Ally AFL-CIO Auburn Seminary African American Ministers In Action Autistic Self Advocacy Network The AIDS Institute Avodah AIDS United BALM Ministries Alan and Leslie Chambers Foundation Bayard Rustin Liberation Initiative American Academy of HIV Medicine Bend the Arc Jewish Action American Academy of Pediatrics Black and Pink American Association for Access, EQuity and Diversity BPFNA ~ Bautistas por la PaZ American Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Brethren Mennonite Council for LGBTQ Interests American Association of University Women (AAUW) Caring Across Generations American Atheists Catholics for Choice American Bar Association Center for American Progress American Civil Liberties Union Center for Black Equity American Conference of Cantors Center for Disability Rights American Counseling Association Center for Inclusivity American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Center for Inquiry Employees (AFSCME) Center for LGBTQ and Gender Studies American Federation of Teachers CenterLink: The Community of LGBT Centers American Heart Association Central Conference -

March 12, 2017 Dear President Emmert & NCAA Governance: On

March 12, 2017 Dear President Emmert & NCAA Governance: On behalf of the undersigned, the Human Rights Campaign and Athlete Ally strongly encourage the NCAA to reaffirm its commitment to operating championships and events that are safe, healthy, and free from discrimination; and are held in sites where the dignity of everyone involved -- from athletes and coaches, to students and workers -- is assured. The NCAA has already demonstrated its commitment to ensuring safe and inclusive events. In response to state legislatures passing laws targeting LGBTQ people, the NCAA required that bidders seeking to host tournaments or events demonstrate how they will ensure the safety of all participants and spectators, and protect them from discrimination. Based on the new guidelines, the NCAA relocated events scheduled to be held in North Carolina due to the state’s discriminatory HB2 law. We commend these previous actions. With the next round of site selections underway, we urge the NCAA to reaffirm these previous commitments to nondiscrimination and inclusion by avoiding venues that are inherently unwelcoming and unsafe for LGBTQ people. Such locations include: ● Venues in cities or states with laws that sanction discrimination against LGBTQ people in goods, services and/or public accommodations; ● Venues in cities and/or states that prevent transgender people from using the bathroom and/or locker room consistent with their gender identity;1 ● Venues at schools that request Title IX exemptions to discriminate against students based on their sexual orientation and/or gender identity; and ● Venues in states that preempt or override local nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ people. The presence of even one of these factors would irreparably undermine the NCAA’s ability to ensure the health, safety and dignity of event participants. -

LGBTQ Organizations Unite in Calling for Transformational Change in Policing

LGBTQ Organizations Unite in Calling for Transformational Change in Policing Black people have been killed, Black people are dying at the hands of police, our country is in crisis, and we all need to take action. We cannot sit on the sidelines, we cannot acquiesce, and we cannot assign responsibility to others. We, as leaders in the LGBTQ movement, must rise up and call for structural change, for divestment of police resources and reinvestment in communities, and for long-term transformational change. Now is the time to take action, and this letter amplifies our strong calls for urgent and immediate action to be taken. Ongoing police brutality and systemic racism have plagued this nation for generations and have been captured on video and laid bare to the public in the United States and around the world. In 2019, more than 1,000 people were killed at the hands of the police.1 We mourn the unacceptable and untimely deaths of Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, Philando Castile, Eric Garner, Stephon Clark, Freddie Gray, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Mya Hall, Tony McDade, Rayshard Brooks, and many more who were gone too soon. We have seen with increased frequency the shocking video footage of police brutality. Officers have been recorded instigating violence, screaming obscenities, dragging individuals out of cars, using unnecessary force, holding individuals at gunpoint, and kneeling on peoples’ necks to the desperate plea of “I can’t breathe.” These occurrences are stark reminders of a police system that needs structural changes, deconstruction, and transformation. No one should fear for their lives when they are pulled over by the police. -

Employment Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Michigan

Employment Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Michigan Christy Mallory and Brad Sears February 2015 Executive Summary More than 4% of the American workforce identifies as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT). Approximately 184,000 of these workers live in Michigan. Michigan does not have a statewide law that prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity in both public and private sector employment. This report summarizes recent evidence of sexual orientation and gender identity employment discrimination, explains the limited current protections from sexual orientation and gender identity employment discrimination in Michigan, and estimates the administrative impact of passing a law prohibiting employment discrimination based on these characteristics in the state. 184,000 32% 84% 65% 16% 86 Estimated Income Workforce Transgender New Disparity Public Support Covered by Workers Complaints if Number of between for LGBT LGBT-Inclusive Reporting LGBT LGBT Workers Straight and Workplace Local Non- Workplace Protections Gay Male Protections Discrimination Discrimination are Added to Workers Laws State Laws Same-sex couples per 1,000 households, Discrimination experienced by transgender by Census tract (adjusted) workers in Michigan1 84% 44% 34% 23% Harassed or Not Hired Lost a Job Denied a Mistreated Promotion 1 Key findings of this report include: • In total there are approximately 300,000 LGBT adults in Michigan, including nearly 184,000 who are part of Michigan’s workforce.2 • Media reports, lawsuits, and complaints to community-based organizations document incidents of sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination against employees in Michigan. These include reports from a CEO, a nursing assistant, and a local government employee. -

LGBT Tra Ally Aining Proje G Ma Ect S Anua Safe Al

LGBT Ally Project Safe Training Manual Compiled & Edited by: Jamiil Gaston Office of Student Engagement, Multicultural Programs Melissa Grunow, M.A. Office of Leadership Programs and First Year Experience Lawrence Technological University 2012 1 2 Contents Introduction 3 Terms & Definitions 4‐5 Sexual Orientation 6‐7 Gender Identity 8 Signs & Symbols 9‐11 LGBT History 12 Laws & Policy: USA 13 Laws & Policy: Michigan 14 Laws & Policy: LTU 15 Coming Out 16 Being an Ally 17 Additional Resources 18 3 Introduction How to Use this Manual The ever‐changing landscape of the LGBT community and political atmosphere surrounding LGBT issues makes it difficult to create a standalone permanent manual. This manual has been compiled as a counterpart to the Project Safe Training. The myriad of resources included on the Project Safe Training disk will be referred to in many sections of this manual in addition to various internet resource links. We like to recognize the work that has been/is being done, not only at Lawrence Technological University, but other schools, colleges, universities, and grassroots and community organizations around the United States and world. We have done our best to include or link to as many of those resources as possible. You will find many sections of this manual contain a simple statement redirecting you to one of those resources. *If you find a resource missing or broken link, or would like us to consider including any additional resources please email [email protected]. Mission & Goals The mission of Project Safe is to provide a safe, nonjudgmental campus environment for all LTU students, faculty, staff, and allies who may have questions and/or concerns related to gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender issues. -

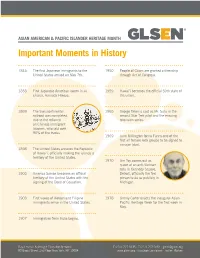

GLSEN Apihistory Timeline.Pdf

ASIAN AMERICAN & PACIFIC ISLANDER HERITAGE MONTH Important Moments in History 1843 The first Japanese immigrants to the 1950 People of Guam are granted citizenship United States arrived on May 7th. through Act of Congress. 1858 First Japanese American sworn in as 1959 Hawai’i becomes the official 50th state of citizen, Hamada Hikozo. the union. 1869 The transcontinental 1965 George Takei is cast as Mr. Sulu in the railroad was completed, second Star Trek pilot and the ensuing due to the reliance television series. on Chinese immigrant laborers, who laid over 90% of the tracks. 1969 June Millington forms Fanny-one of the first all female rock groups to be signed to a major label. 1898 The United States annexes the Republic of Hawai’i, officially making the islands a territory of the United States. 1970 Jim Toy comes out as queer at an anti-Vietnam rally in Kennedy Square, 1900 America Samoa becomes an official Detroit, officially the first territory of the United States with the person to do so publicly in signing of the Deed of Cessation. Michigan. 1903 First waves of Korean and Filipino 1978 Jimmy Carter enacts the inaugural Asian- immigrants arrive in the United States. Pacific Heritage Week for the first week in May. 1907 Immigration from India begins. Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network T (212) 727 0135 · F (212) 727 0254 · [email protected] 90 Broad Street, 2nd Floor New York, NY 10004 www.glsen.org · facebook.com/glsen · twitter: @glsen 1979 Lesbian and Gay Asian Alliance founded 2002 Ghalib Shiraz Dhalla publishes Ode to to address the impact of racism on gay Lata, one of the first novels to tackle and lesbian Asian Pacific American South Asian gay life from the perspective communities. -

Fact Sheet LGBTQ+ Adult

LIVINGSTON COUNTY HUMAN SERVICES COLLABORATIVE BODY Health and Human Service Needs ADULT FACT SHEET LGBTQ+ in Livingston County September 2019 What does LGBTQ+ stand for? LGBTQ is an acronym for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer or questioning. These terms are used to describe a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity. The + sign is inclusive to all other terms used to describe a person’s sexual orientation and gender identity. You can find definitions for these terms at the following link: https://bit.ly/2srceH4. Why is this issue so important to Livingston County? According to the 2015-16 American Community Data for Michigan, 3.8% of people identify as LGBTQ adults and an additional .43% identify as transgender. In 2010 there was 142 same sex households in Livingston County. According to the National Institutes of Health, there are 1.5 million gay, lesbian and bisexual people over 65 living in the US currently and that number is expected to double by 2030. These older adults face additional challenges as they seek both medical and household supports. What are the Alarming Facts? From the National LGBTQ Task Force Survey: 19% reported being refused medical care outright because they were transgender or gender non- conforming. 28% reported they were subjected to harassment in medical settings 50% reported having to teach their medical providers about transgender care 41% reported attempting suicide compared to 1.6% of the general population. According to the National Intimate Partner and sexual violence survey of 2010: 44% of lesbian women and 61% of bisexual women and 26% of gay men and 37% of bisexual men experienced rape, physical violence and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime. -

Orgs Endorsing Equality Act 3-15-21

638 ORGANIZATIONS ENDORSING THE EQUALITY ACT National Organizations 9to5, National Association of Working Women Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance (APALA) A Better Balance Association of Flight Attendants – CWA A. Philip Randolph Institute Association of Title IX Administrators - ATIXA ACRIA Association of Welcoming and Affirming Baptists ADAP Advocacy Association Athlete Ally Advocates for Youth Auburn Seminary AFGE Autistic Self Advocacy Network AFL-CIO Avodah African American Ministers In Action BALM Ministries The AIDS Institute Bayard Rustin Liberation Initiative AIDS United Bend the Arc Jewish Action Alan and Leslie Chambers Foundation Black and Pink American Academy of HIV Medicine BPFNA ~ Bautistas por la PaZ American Academy of Pediatrics Brethren Mennonite Council for LGBTQ Interests American Association for Access, EQuity and Diversity Caring Across Generations American Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Catholics for Choice American Association of University Women (AAUW) Center for American Progress American Atheists Center for Black Equity American Bar Association Center for Disability Rights American Civil Liberties Union Center for Inclusivity American Conference of Cantors Center for Inquiry American Counseling Association Center for LGBTQ and Gender Studies American Federation of State, County, and Municipal CenterLink: The Community of LGBT Centers Employees (AFSCME) Central Conference of American Rabbis American Federation of Teachers Chicago Theological Seminary American Heart Association Child Welfare