Fighting for Inclusion: the Origin of Gay Liberation at the University of Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Domestic Violence in TLGBIQ Communities

Resources What is domestic violence ? SafeHouse Services are all free, confidential, and inclusive. We provide: Domestic or relationship violence is a pattern of behavior where one person 24 Hour Help Line: 734-995-5444 tries to control any other person who is Help getting a protection order Legal advocacy Domestic close to them using tactics of power Counseling and control. It can include physical, Safety Planning Violence in emotional, sexual, spiritual and/or Support Groups Shelter economic abuse. TLGBIQ Local Resources: Domestic violence is a gendered crime Jim Toy Community Center : 734- Communities and is rooted in patriarchy. We 995-9867 http://www.wrap- recognize that domestic violence is up.org/ mostly committed by men against The Neutral Zone (734) 214- women. However, SafeHouse Center also 9995 http://www.neutral- realizes that sexual assault does occur zone.org/ against all genders and across all Parents Families & Friends of A Resource for sexual orientations. That being said, we Lesbians & Gays (PFLAG) Ann do work to end the oppression of all Arbor 734-741-0659 Transgender, Lesbian, people as well as value and celebrates http://www.pflagaa.org/ the diversity of our community. Pride Zone at Ozone Center Bisexual, Gay, Intersex, SafeHouse Center also strives to protect (734)662-2265 Queer/Questioning the rights of everyone. http://ozonehouse.org/programs SafeHouse Center /queerzone.php Survivors of Domestic Spectrum Center 734-763-4186 http://spectrumcenter.umich.edu Violence How can I h elp my friend or (U of -

Issues in Issues Issues in Race & Society

Issues in Issues in Race & Society Issues in Race & Society Race Volume 8 | Issue 1 The Complete 2019 Edition In this Issue: Race & Africana Demography: Lessons from Founders E. Franklin Frazier, W.E.B. DuBois, and the Atlanta School of Sociology — Lori Latrice Martin Subjective Social Status, Reliliency Resources, and Self-Concept among Employed African Americans — Verna Keith and Maxine Thompson Exclusive Religious Beliefs and Social Capital: Unpacking Nuances in the Relationship between Religion and Social Capital Formation Society — Daniel Auguste More than Just Incarceration: Law Enforcement Contact and Black Fathers’ Familial Relationships — Deadrick T. Williams and Armon R. Perry An Interdisciplinary Global Journal Training the Hands, the Head, and the Heart: Student Protest and Activism at Hampton Institute During the 1920s — James E. Alford “High Tech Lynching:” White Virtual Mobs and University Administrators Volume 8 | The Complete 2019 Edition 2019 Complete 8 | The Volume as Policing Agents in Higher Education — Biko Mandela Gray, Stephen C. Finley, Lori Latrice Martin Racialized Categorical Inequality: Elaborating Educational Theory to Explain African American Disparities in Public Schools — Geoffrey L. Wood Black Women’s Words: Unsing Oral History to Understand the Foundations of Black Women’s Educational Advocacy — Gabrielle Peterson ABSASSOCIATION OF Suicide in Color: Portrayals of African American Suicide in Ebony Magazine from 1960-2008 — Kamesha Spates BLACK SOCIOLOGISTS ISBN 978-1-947602-67-0 ISBN 978-1-947602-67-0 90000> VolumePublished 8 |by Thethe Association Complete of Black2019 Sociologists Edition 9 781947 602670 Do Guys Just Want to Have Fun? Issues in Race & Society An Interdisciplinary Global Journal Volume 8 | Issue 1 The Complete 2019 Edition © Association of Black Sociologists | All rights reserved. -

The Year 1969 Marked a Major Turning Point in the Politics of Sexuality

The Gay Pride March, begun in 1970 as the In the fertile and tumultuous year that Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade to followed, groups such as the Gay commemorate the Stonewall Riots, became an Liberation Front (GLF), Gay Activists annual event, and LGBT Pride months are now celebrated around the world. The march, Alliance (GAA), and Radicalesbians Marsha P. Johnson handing out flyers in support of gay students at NYU, 1970. Photograph by Mattachine Society of New York. “Where Were Diana Davies. Diana Davies Papers. which demonstrates gays, You During the Christopher Street Riots,” The year 1969 marked 1969. Mattachine Society of New York Records. sent small groups of activists on road lesbians, and transgender people a major turning point trips to spread the word. Chapters sprang Gay Activists Alliance. “Lambda,” 1970. Gay Activists Alliance Records. Gay Liberation Front members marching as articulate constituencies, on Times Square, 1969. Photograph by up across the country, and members fought for civil rights in the politics of sexuality Mattachine Society of New York. Diana Davies. Diana Davies Papers. “Homosexuals Are Different,” 1960s. in their home communities. GAA became a major activist has become a living symbol of Mattachine Society of New York Records. in America. Same-sex relationships were discreetly force, and its SoHo community center, the Firehouse, the evolution of LGBT political tolerated in 19th-century America in the form of romantic Jim Owles. Draft of letter to Governor Nelson A. became a nexus for New York City gays and lesbians. Rockefeller, 1970. Gay Activists Alliance Records. friendships, but the 20th century brought increasing legal communities. -

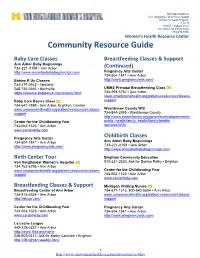

Community Resource Guide

Michigan Medicine Von Voigtlander Women’s Hospital Women’s Health Program Floor 9 1540 E. Hospital Drive Ann Arbor, MI 48109-4276 734-936-8886 Women’s Health Resource Center Community Resource Guide Baby Care Classes Breastfeeding Classes & Support Ann Arbor Baby Beginnings 734-221-0158 ▪ Ann Arbor (Continued) http://www.annarborbabybeginnings.com/ Pregnancy Arts Center 734-604-1841 ▪ Ann Arbor Babies R Us Classes http://www.pregnancyarts.com/ 734-477-0943 ▪ Ypsilanti 248-735-0365 ▪ Northville UMHS Prenatal Breastfeeding Class https://reserve.babiesrus.com/events.html\ 734-998-5782 ▪ Ann Arbor www.umwomenshealth.org/patient-resources/classes- Baby Care Basics Class support 734-647-7888 ▪ Ann Arbor, Brighton, Canton www.umwomenshealth.org/patient-resources/classes- Washtenaw County WIC support 734-544-2995 ▪ Washtenaw County http://www.ewashtenaw.org/government/departments/ Center for the Childbearing Year public_health/family_health/family-health- 734-663-1523 ▪ Ann Arbor services/WIC/ www.center4cby.com Pregnancy Arts Center Childbirth Classes 734-604-1841 ▪ Ann Arbor Ann Arbor Baby Beginnings http://www.pregnancyarts.com/ 734-221-0158 ▪ Ann Arbor http://www.annarborbabybeginnings.com/ Birth Center Tour Brighton Community Education Von Voigtlander Women’s Hospital 810-231-2820, Ask for Denise Pelky ▪ Brighton 734-763-6295 ▪ Ann Arbor www.umwomenshealth.org/patient-resources/classes- Center for the Childbearing Year support 734-663-1523 ▪ Ann Arbor www.center4cby.com Breastfeeding Classes & Support Michigan Visiting Nurses Breastfeeding -

Queer Alchemy: Fabulousness in Gay Male Literature and Film

QUEER ALCHEMY QUEER ALCHEMY: FABULOUSNESS IN GAY MALE LITERATURE AND FILM By ANDREW JOHN BUZNY, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Andrew John Buzny, August 2010 MASTER OF ARTS (2010) McMaster University' (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Queer Alchemy: Fabulousness in Gay Male Literature and Film AUTHOR: Andrew John Buzny, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Lorraine York NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 124pp. 11 ABSTRACT This thesis prioritizes the role of the Fabulous, an underdeveloped critical concept, in the construction of gay male literature and film. Building on Heather Love's observation that queer communities possess a seemingly magical ability to transform shame into pride - queer alchemy - I argue that gay males have created a genre of fiction that draws on this alchemical power through their uses of the Fabulous: fabulous realism. To highlight the multifarious nature of the Fabulous, I examine Thomas Gustafson's film Were the World Mine, Tomson Highway's novel Kiss ofthe Fur Queen, and Quentin Crisp's memoir The Naked Civil Servant. 111 ACKNO~EDGEMENTS This thesis would not have reached completion without the continuing aid and encouragement of a number of fabulous people. I am extremely thankful to have been blessed with such a rigorous, encouraging, compassionate supervisor, Dr. Lorraine York, who despite my constant erratic behaviour, and disloyalty to my original proposal has remained a strong supporter of this project: THANK YOU! I would also like to thank my first reader, Dr. Sarah Brophy for providing me with multiple opportunities to grow in~ellectually throughout the past year, and during my entire tenure at McMaster University. -

Providing Culturally and Clinically Competent Care for 2SLGBTQ Seniors: Inclusion, Diversity and Equity

Providing Culturally and Clinically Competent Care for 2SLGBTQ Seniors: Inclusion, Diversity and Equity Devan Nambiar, MSc. Acting Program Manger & Education & Training Facilitator E: [email protected] October 22, 2019 2 LT outcomes Group Norms • Give yourself permission to make • Create practical steps to inclusive and safe spaces for SOGI mistakes & have a process to -Deconstruct your address mistakes • Understand 2SLGBTQ+ health disparities ideology, values, • Use “I” statements beliefs systems • Use correct pronouns (he, she, • Competencies in clinical, cultural safety, from religions, cultural humility attitude, morality and they….) implicit biases • Agree to disagree • Become an ally • Create safe space for all to learn -Being comfortable with not knowing • Respect confidentiality and questioning your • Share wisdom & Share airtime discomfort with SOGI 3 SOGI-sexual orientation and gender identity 4 Trans Mentorship Call biweekly -1st & 3rd week on Wednesday 12 noon -1 pm Must register 5 online 6 1 Does Discussions Myths on 2SLGBTQ heterosexuality end at senior • At school, either college and/ or university have you learnt about LGBT2SQ age? clients or in population health? • When did you decide you are heterosexual? How do you know you are 100% heterosexual? • You stop being 2SLGBTQ if you are older, a senior, • Are you familiar with gender neutral pronouns? retired, have an illness • Are there staff who are out at work as LGBT2SQ? • Do you know LGBT2SQ people outside work? • • Have you done an assessment for HRT? -

Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives in Archives of Sexuality & Gender, Part I: LGBTQ History and Culture Since 1940

The Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives in Archives of Sexuality & Gender, Part I: LGBTQ History and Culture Since 1940 Publisher’s Foreword CGA became a separate body, although it shared offices Gale, a part of Cengage Learning, is proud to present with TBP until that paper’s demise in 1987. Pink Triangle Archives of Sexuality & Gender, Part I: LGBTQ History and Press was formed in 1976 to provide more legal stability for Culture Since 1940. This landmark digital archive includes the TBP, and CGA was part of the Press although an autonomous International Periodicals and Newsletter collection from the entity. The CGA became an Ontario corporation on Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives, amongst other March 31, 1980, and eventually received registered materials from leading archives and libraries. Archives of charitable status in November 1981. The Archives was the Sexuality & Gender, Part I: LGBTQ History and Culture Since first lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender (lgbt) organization in 1940 supports research and teaching in subjects such as Canada to receive this status, which would prove useful in queer history and activism, cultural studies, psychology, the years ahead. The Archives always operated on a limited sociology, health, political science, policy studies, human budget, and being able to provide tax receipts for donations rights, gender studies, and more with more than 1.5 million of materials or funds has helped to build holdings, especially pages of primary source content. lgbt periodicals. The Archives holds a large periodical collection and The Canadian Lesbian substantial vertical files of flyers, clippings, brochures, and Gay Archives and other ephemera produced by lgbt individuals and organizations. -

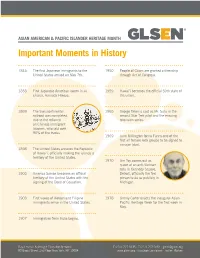

GLSEN Apihistory Timeline.Pdf

ASIAN AMERICAN & PACIFIC ISLANDER HERITAGE MONTH Important Moments in History 1843 The first Japanese immigrants to the 1950 People of Guam are granted citizenship United States arrived on May 7th. through Act of Congress. 1858 First Japanese American sworn in as 1959 Hawai’i becomes the official 50th state of citizen, Hamada Hikozo. the union. 1869 The transcontinental 1965 George Takei is cast as Mr. Sulu in the railroad was completed, second Star Trek pilot and the ensuing due to the reliance television series. on Chinese immigrant laborers, who laid over 90% of the tracks. 1969 June Millington forms Fanny-one of the first all female rock groups to be signed to a major label. 1898 The United States annexes the Republic of Hawai’i, officially making the islands a territory of the United States. 1970 Jim Toy comes out as queer at an anti-Vietnam rally in Kennedy Square, 1900 America Samoa becomes an official Detroit, officially the first territory of the United States with the person to do so publicly in signing of the Deed of Cessation. Michigan. 1903 First waves of Korean and Filipino 1978 Jimmy Carter enacts the inaugural Asian- immigrants arrive in the United States. Pacific Heritage Week for the first week in May. 1907 Immigration from India begins. Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network T (212) 727 0135 · F (212) 727 0254 · [email protected] 90 Broad Street, 2nd Floor New York, NY 10004 www.glsen.org · facebook.com/glsen · twitter: @glsen 1979 Lesbian and Gay Asian Alliance founded 2002 Ghalib Shiraz Dhalla publishes Ode to to address the impact of racism on gay Lata, one of the first novels to tackle and lesbian Asian Pacific American South Asian gay life from the perspective communities. -

Fact Sheet LGBTQ+ Adult

LIVINGSTON COUNTY HUMAN SERVICES COLLABORATIVE BODY Health and Human Service Needs ADULT FACT SHEET LGBTQ+ in Livingston County September 2019 What does LGBTQ+ stand for? LGBTQ is an acronym for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer or questioning. These terms are used to describe a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity. The + sign is inclusive to all other terms used to describe a person’s sexual orientation and gender identity. You can find definitions for these terms at the following link: https://bit.ly/2srceH4. Why is this issue so important to Livingston County? According to the 2015-16 American Community Data for Michigan, 3.8% of people identify as LGBTQ adults and an additional .43% identify as transgender. In 2010 there was 142 same sex households in Livingston County. According to the National Institutes of Health, there are 1.5 million gay, lesbian and bisexual people over 65 living in the US currently and that number is expected to double by 2030. These older adults face additional challenges as they seek both medical and household supports. What are the Alarming Facts? From the National LGBTQ Task Force Survey: 19% reported being refused medical care outright because they were transgender or gender non- conforming. 28% reported they were subjected to harassment in medical settings 50% reported having to teach their medical providers about transgender care 41% reported attempting suicide compared to 1.6% of the general population. According to the National Intimate Partner and sexual violence survey of 2010: 44% of lesbian women and 61% of bisexual women and 26% of gay men and 37% of bisexual men experienced rape, physical violence and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime. -

Halperin David M Traub Valeri

GAY SHAME DAVID M. HALPERIN & VALERIE TRAUB I he University of Chicago Press C H I C A G 0 A N D L 0 N D 0 N david m. h alperin is theW. H. Auden Collegiate Professor of the History and Theory of Sexuality at the University of Michigan. He is the author of several books, including Saint Foucault: Towards a Gay Hagiography (Oxford University Press, 1995) and, most re cently, What Do Gay Men Want? An Essay on Sex, Risk, and Subjectivity (University of Michi gan Press, 2007). valerie traub is professor ofEnglish andwomen's studies at the Uni versity of Michigan, where she chairs the Women's Studies Department. She is the author of Desire and Anxiety: Circulations of Sexuality in Shakesptanan Drama (Routledge, 1992) and The Renaissance of Ltsbianism in Early Modem England (Cambridge University Press, 2002). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2009 by The University of Chicago Al rights reserved. Published 2009 Printed in the United States of America 17 16 15 14 13 12 ii 10 09 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-31437-2 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-31438-9 (paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-31437-5 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-31438-3 (paper) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gay shame / [edited by] David M. Halperin and Valerie Traub. p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-31437-2 (cloth: alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-31437-5 (cloth: alk. -

Gay Shame in a Geopolitical Context

Gay shame in a geopolitical context Article (Accepted Version) Munt, Sally R (2018) Gay shame in a geopolitical context. Cultural Studies, 33 (2). pp. 223-248. ISSN 0950-2386 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/73415/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Gay Shame in a Geopolitical Context Sally R Munt Sussex Centre for Cultural Studies, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK Email: [email protected] Postal address: School of Media, Film and Music, Silverstone Building, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton, UK BN1 9RG Sally R Munt is Professor of Gender and Cultural Studies at the University of Sussex, UK. -

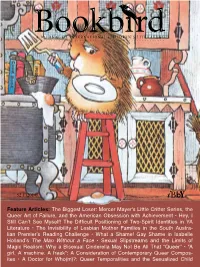

Mercer Mayer's Little Critter Series, the Queer Art of Failure, and The

52.1 (2014) Feature Articles: The Biggest Loser: Mercer Mayer's Little Critter Series, the Queer Art of Failure, and the American Obsession with Achievement • Hey, I Still Can’t See Myself! The Difficult Positioning of Two-Spirit Identities in YA Literature • The Invisibility of Lesbian Mother Families in the South Austra- lian Premier’s Reading Challenge • What a Shame! Gay Shame in Isabelle Holland’s The Man Without a Face • Sexual Slipstreams and the Limits of Magic Realism: Why a Bisexual Cinderella May Not Be All That “Queer” • "A girl. A machine. A freak”: A Consideration of Contemporary Queer Compos- ites • A Doctor for Who(m)?: Queer Temporalities and the Sexualized Child The Journal of IBBY, the International Board on Books for Young People Copyright © 2014 by Bookbird, Inc. Reproduction of articles in Bookbird requires permission in writing from the editor. Editor: Roxanne Harde, University of Alberta—Augustana Faculty (Canada) Address for submissions and other editorial correspondence: [email protected] Bookbird’s editorial office is supported by the Augustana Faculty at the University of Alberta, Camrose, Alberta, Canada. Editorial Review Board: Peter E. Cumming, York University (Canada); Debra Dudek, University of Wollongong (Australia); Libby Gruner, University of Richmond (USA); Helene Høyrup, Royal School of Library & Information Science (Denmark); Judith Inggs, University of the Witwatersrand (South Africa); Ingrid Johnston, University of Albert, Faculty of Education (Canada); Shelley King, Queen’s University (Canada); Helen Luu, Royal Military College (Canada); Michelle Martin, University of South Carolina (USA); Beatriz Alcubierre Moya, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos (Mexico); Lissa Paul, Brock University (Canada); Laura Robinson, Royal Military College (Canada); Bjorn Sundmark, Malmö University (Sweden); Margaret Zeegers, University of Ballarat (Australia); Board of Bookbird, Inc.