7017 1478289112.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Reframing of Metin Erksan's Time to Love

Auteur and Style in National Cinema: A Reframing of Metin Erksan's Time to Love Murat Akser University of Ulster, [email protected] Volume 3.1 (2013) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2013.57 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract This essay will hunt down and classify the concept of the national as a discourse in Turkish cinema that has been constructed back in 1965, by the film critics, by filmmakers and finally by today’s theoretical standards. So the questions we will be constantly asking throughout the essay can be: Is what can be called part of national film culture and identity? Is defining a film part of national heritage a modernist act that is also related to theories of nationalism? Is what makes a film national a stylistic application of a particular genre (such as melodrama)? Does the allure of the film come from the construction of a hero-cult after a director deemed to be national? Keywords: Turkish cinema, national cinema, nation state, Metin Erksan, Yeşilçam New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Auteur and Style in National Cinema: A Reframing of Metin Erksan's Time to Love Murat Akser Twenty-five years after its publication in 1989, Andrew Higson’s conceptualization of national cinema in his seminal Screen article has been challenged by other film scholars. -

PATRIARCHAL STRUCTURES and PRACTICES in TURKEY: the CASE of SOCIAL REALIST and NATIONAL FILMS of 1960S

PATRIARCHAL STRUCTURES AND PRACTICES IN TURKEY: THE CASE OF SOCIAL REALIST AND NATIONAL FILMS OF 1960s A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF THE MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY HAT İCE YE Şİ LDAL ŞEN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY OCTOBER 2005 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sibel Kalaycıo ğlu Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Mehmet C. Ecevit Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Kurtulu ş Kayalı (DTCF, Hist) Prof. Dr. Mehmet C. Ecevit (METU, Soc.) Prof. Dr. Yıldız Ecevit (METU, Soc.) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Filiz Kardam (Çankaya U. ADM) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mesut Ye ğen (METU, Soc.) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Hatice Ye şildal Şen Signature : iii ABSTRACT PATRIARCHAL STRUCTURES AND PRACTICES IN TURKEY: THE CASE OF SOCIAL REALIST AND NATIONAL FILMS OF 1960s Ye şildal Şen, Hatice Ph. D., Department of Sociology Supervisor: Prof. -

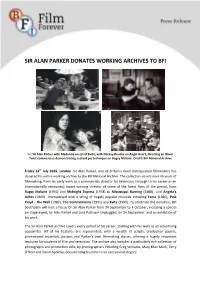

Sir Alan Parker Donates Working Archives to Bfi

SIR ALAN PARKER DONATES WORKING ARCHIVES TO BFI l-r: Sir Alan Parker with Madonna on set of Evita; with Mickey Rourke on Angel Heart; directing an Oliver Twist commercial; demonstrating custard pie technique on Bugsy Malone. Credit: BFI National Archive Friday 24th July 2015, London. Sir Alan Parker, one of Britain’s most distinguished filmmakers has donated his entire working archive to the BFI National Archive. The collection covers over 45 years of filmmaking, from his early work as a commercials director for television, through to his career as an internationally renowned, award-winning director of some of the finest films of the period, from Bugsy Malone (1976) and Midnight Express (1978) to Mississippi Burning (1988) and Angela’s Ashes (1999) interspersed with a string of hugely popular musicals including Fame (1980), Pink Floyd - The Wall (1982), The Commitments (1991) and Evita (1996). To celebrate the donation, BFI Southbank will host a Focus On Sir Alan Parker from 24 September to 4 October, including a special on stage event, Sir Alan Parker and Lord Puttnam Unplugged, on 24 September, and an exhibition of his work. The Sir Alan Parker archive covers every period of his career, starting with his work as an advertising copywriter. All of his features are represented, with a wealth of scripts, production papers, promotional materials, posters and Parker’s own filmmaking diaries, offering a hugely important resource for students of film and television. The archive also includes a particularly rich collection of photographs and production stills, by photographers including Greg Williams, Mary Ellen Mark, Terry O'Neill and David Appleby, documenting his films to an exceptional degree. -

Cinema and Politics

Cinema and Politics Cinema and Politics: Turkish Cinema and The New Europe Edited by Deniz Bayrakdar Assistant Editors Aslı Kotaman and Ahu Samav Uğursoy Cinema and Politics: Turkish Cinema and The New Europe, Edited by Deniz Bayrakdar Assistant Editors Aslı Kotaman and Ahu Samav Uğursoy This book first published 2009 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2009 by Deniz Bayrakdar and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-0343-X, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-0343-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Images and Tables ......................................................................... viii Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Preface ........................................................................................................ xi Introduction ............................................................................................. xvii ‘Son of Turks’ claim: ‘I’m a child of European Cinema’ Deniz Bayrakdar Part I: Politics of Text and Image Chapter One ................................................................................................ -

Café Society

Presents CAFÉ SOCIETY A film by Woody Allen (96 min., USA, 2016) Language: English Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1352 Dundas St. West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1Y2 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com @MongrelMedia MongrelMedia CAFÉ SOCIETY Starring (in alphabetical order) Rose JEANNIE BERLIN Phil STEVE CARELL Bobby JESSE EISENBERG Veronica BLAKE LIVELY Rad PARKER POSEY Vonnie KRISTEN STEWART Ben COREY STOLL Marty KEN STOTT Co-starring (in alphabetical order) Candy ANNA CAMP Leonard STEPHEN KUNKEN Evelyn SARI LENNICK Steve PAUL SCHNEIDER Filmmakers Writer/Director WOODY ALLEN Producers LETTY ARONSON, p.g.a. STEPHEN TENENBAUM, p.g.a. EDWARD WALSON, p.g.a. Co-Producer HELEN ROBIN Executive Producers ADAM B. STERN MARC I. STERN Executive Producer RONALD L. CHEZ Cinematographer VITTORIO STORARO AIC, ASC Production Designer SANTO LOQUASTO Editor ALISA LEPSELTER ACE Costume Design SUZY BENZINGER Casting JULIET TAYLOR PATRICIA DiCERTO 2 CAFÉ SOCIETY Synopsis Set in the 1930s, Woody Allen’s bittersweet romance CAFÉ SOCIETY follows Bronx-born Bobby Dorfman (Jesse Eisenberg) to Hollywood, where he falls in love, and back to New York, where he is swept up in the vibrant world of high society nightclub life. Centering on events in the lives of Bobby’s colorful Bronx family, the film is a glittering valentine to the movie stars, socialites, playboys, debutantes, politicians, and gangsters who epitomized the excitement and glamour of the age. Bobby’s family features his relentlessly bickering parents Rose (Jeannie Berlin) and Marty (Ken Stott), his casually amoral gangster brother Ben (Corey Stoll); his good-hearted teacher sister Evelyn (Sari Lennick), and her egghead husband Leonard (Stephen Kunken). -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Graham Walker Film Music Producer / Music Production Supervisor

GRAHAM WALKER FILM MUSIC PRODUCER / MUSIC PRODUCTION SUPERVISOR Graham is one of Britain’s most experienced and active Music Producers specialising in the international film music business. Education Graham studied music at Kneller Hall, the Royal Military School of Music and the Guildhall School of Music in London after which he began his career in the music production business. Graham is also a good musician; a trumpet player. Graham is one of Britain’s most experienced and active Music Producers specialising in the international film music business. After a distinguished career as Musical Director of Yorkshire Television, Head of Music for Granada Television and Head of Film Music Production for Lord Grade’s ITC Films, Graham then became freelance. The first 6 years of Graham’s career were spent at the world famous KPM Production Music Library; that was the day job! The night job was arranging and conducting sessions for various ‘pop’ and variety stars’ singles and albums such as Dickie Henderson, Roy Castle, Nicko McBrain (the drummer from Iron Maiden) and the number 1 hit ‘Grandad’ performed by Clive Dunn(!) plus score takedowns for the BBC’s ‘Top of the Pops’ for US groups such as ‘The Four Tops,’ Diana Ross and The Supremes,’ Otis Redding,’ ‘Marvin Gaye’ and many others. Work: Musical Director - Yorkshire Television, Head of Music - Granada Television, Head of Film Production (Music) - Lord Grade’s ITC Films, Head of Music - Zenith Productions. Over the years Graham has acquired extensive expertise in recording throughout Europe and beyond. He has worked with many composers, musicians and orchestras in the recording centres of London, New York, Paris, Munich, Cologne, Rome, Brussels, Berlin, Budapest, Moscow, Belgrade, Prague, Bratislava, Brandenburg and various locations in South Africa. -

THE MYTH of 'TERRIBLE TURK' and 'LUSTFUL TURK' Nevs

THE WESTERN IMAGE OF TURKS FROM THE MIDDLE AGES TO THE 21ST CENTURY: THE MYTH OF ‘TERRIBLE TURK’ AND ‘LUSTFUL TURK’ Nevsal Olcen Tiryakioglu A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 Copyright Statement This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed in the owner(s) of the Intellectual Property Rights. i Abstract The Western image of Turks is identified with two distinctive stereotypes: ‘Terrible Turk’ and ‘Lustful Turk.’ These stereotypical images are deeply rooted in the history of the Ottoman Empire and its encounters with Christian Europe. Because of their fear of being dominated by Islam, European Christians defined the Turks as the wicked ‘Other’ against their perfect ‘Self.’ Since the beginning of Crusades, the Western image of Turks is associated with cruelty, barbarity, murderousness, immorality, and sexual perversion. These characteristics still appear in cinematic representations of Turks. In Western films such as Lawrence of Arabia and Midnight Express, the portrayals of Turks echo the stereotypes of ‘terrible Turk’ and ‘lustful Turk.’ This thesis argues that these stereotypes have transformed into a myth and continued to exist uniformly in Western contemporary cinema. The thesis attempts to ascertain the uniformity and consistency of the cinematic image of Turks and determine the associations between this image and the myths of ‘terrible Turk’ and ‘lustful Turk.’ To achieve this goal, this thesis examines the trajectory of the Turkish image in Western discourse between the 11th and 21st centuries. -

Ancient Greek Myth and Drama in Greek Cinema (1930–2012): an Overall Approach

Konstantinos KyriaKos ANCIENT GREEK MYTH AND DRAMA IN GREEK CINEMA (1930–2012): AN OVERALL APPROACH Ι. Introduction he purpose of the present article is to outline the relationship between TGreek cinema and themes from Ancient Greek mythology, in a period stretching from 1930 to 2012. This discourse is initiated by examining mov- ies dated before WW II (Prometheus Bound, 1930, Dimitris Meravidis)1 till recent important ones such as Strella. A Woman’s Way (2009, Panos Ch. Koutras).2 Moreover, movies involving ancient drama adaptations are co-ex- amined with the ones referring to ancient mythology in general. This is due to a particularity of the perception of ancient drama by script writers and di- rectors of Greek cinema: in ancient tragedy and comedy film adaptations,3 ancient drama was typically employed as a source for myth. * I wish to express my gratitude to S. Tsitsiridis, A. Marinis and G. Sakallieros for their succinct remarks upon this article. 1. The ideologically interesting endeavours — expressed through filming the Delphic Cel- ebrations Prometheus Bound by Eva Palmer-Sikelianos and Angelos Sikelianos (1930, Dimitris Meravidis) and the Longus romance in Daphnis and Chloë (1931, Orestis Laskos) — belong to the origins of Greek cinema. What the viewers behold, in the first fiction film of the Greek Cinema (The Adventures of Villar, 1924, Joseph Hepp), is a wedding reception at the hill of Acropolis. Then, during the interwar period, film pro- duction comprises of documentaries depicting the “Celebrations of the Third Greek Civilisation”, romances from late antiquity (where the beauty of the lovers refers to An- cient Greek statues), and, finally, the first filmings of a theatrical performance, Del- phic Celebrations. -

Living Voices Within the Silence Bibliography 1

Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 1 Within the Silence bibliography FICTION Elementary So Far from the Sea Eve Bunting Aloha means come back: the story of a World War II girl Thomas and Dorothy Hoobler Pearl Harbor is burning: a story of World War II Kathleen Kudlinski A Place Where Sunflowers Grow (bilingual: English/Japanese) Amy Lee-Tai Baseball Saved Us Heroes Ken Mochizuki Flowers from Mariko Rick Noguchi & Deneen Jenks Sachiko Means Happiness Kimiko Sakai Home of the Brave Allen Say Blue Jay in the Desert Marlene Shigekawa The Bracelet Yoshiko Uchida Umbrella Taro Yashima Intermediate The Burma Rifles Frank Bonham My Friend the Enemy J.B. Cheaney Tallgrass Sandra Dallas Early Sunday Morning: The Pearl Harbor Diary of Amber Billows 1 Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 2 The Journal of Ben Uchida, Citizen 13559, Mirror Lake Internment Camp Barry Denenberg Farewell to Manzanar Jeanne and James Houston Lone Heart Mountain Estelle Ishigo Itsuka Joy Kogawa Weedflower Cynthia Kadohata Boy From Nebraska Ralph G. Martin A boy at war: a novel of Pearl Harbor A boy no more Heroes don't run Harry Mazer Citizen 13660 Mine Okubo My Secret War: The World War II Diary of Madeline Beck Mary Pope Osborne Thin wood walls David Patneaude A Time Too Swift Margaret Poynter House of the Red Fish Under the Blood-Red Sun Eyes of the Emperor Graham Salisbury, The Moon Bridge Marcia Savin Nisei Daughter Monica Sone The Best Bad Thing A Jar of Dreams The Happiest Ending Journey to Topaz Journey Home Yoshiko Uchida 2 Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 3 Secondary Snow Falling on Cedars David Guterson Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet Jamie Ford Before the War: Poems as they Happened Drawing the Line: Poems Legends from Camp Lawson Fusao Inada The moved-outers Florence Crannell Means From a Three-Cornered World, New & Selected Poems James Masao Mitsui Chauvinist and Other Stories Toshio Mori No No Boy John Okada When the Emperor was Divine Julie Otsuka The Loom and Other Stories R.A. -

Los Vaivenes De Jules Dassin a Lo Largo Del Mundo, Con Melina

PERSONALIDADES (IV) Los vaivenes de Jules Dassin a lo largo del mundo, con Melina Antes de conocer a Melina Mercouri, Ju les Dassin era otro: el cine social norte Fue un realista en USA, donde conoció a Mark Hellinger; americano y el mundo exterior le habían después abandonó su país en tiempos de McCarthy; dado prestigio de realista. Su obra más re después conoció a Melina Mercouri. ciente ha fortalecido la imagen de que Da Una obra muy variada y cambiante, con intereses que oscilan ssin es un apasionado, un humorista y un ad entre el planteo social, la reflexión poética, la alegoría sobre la libertad mirador de lo griego, incluida Melina, los y el individuo, aproximaciones a clásicos griegos, a la personalidad clásicos de la tragedia y el teatro. Claro que el teatro form ó parte de su-primera vocación de la Mercouri, propone, la interrogante de su final definición como creador. y que sus antecedentes son griegos. Empero Las explicaciones se intentan en este análisis. su obra se fractura cuando abandona los Es Lo que no ofrece dudas es que err varios films Dassin ha demostrado tados Unidos y se va a Europa donde en ser capaz de lograr obras mayores 1950 dirige Siniestra obsesión, que prolon y en dos ejemplos concretos alcanzar la maestría. ga su obra previa, y en 1954 Rififi, que es un film policial y se parece a los que hizo en su país entre 1947 y 1950. Dos años des pués hace El que debe morir, que es un rela to apasionado, y dos años después padece la fijación de Melina y la.causa griega, que tie nen sus costados pasionales.