Based on a True Story: a Critical Approach to Ambiguous Veracity in Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History's Mysteries

History’s Mysteries: Research, Discuss and Solve some of History's Biggest Puzzles ISBN: 978-1-956159-00-4 (print) 978-1-956159-01-1 (ebook) Copyright 2021 Taylor Sapp, Catherine Noble, Peter Lacy, Mina Gavell, and Andrew Lawrence All rights reserved. Our authors, editors, and designers work hard to develop original, high-quality content. They deserve compensation. Please respect their efforts and their rights under copyright law. Do not copy, photocopy, or reproduce this book or any part of this book (unless the page is marked PHOTOCOPIABLE) for use inside or outside the classroom, in commercial or non-commercial settings. It is also forbidden to copy, adapt, or reuse this book or any part of this book for use on websites, blogs, or third-party lesson-sharing websites. For permission requests, write to the publisher at “ATTN: Permissions”, at the address below: 1024 Main St. #172 Branford, CT 06405 USA [email protected] www.AlphabetPublishingBooks.com Discounts on class sets and bulk orders available upon inquiry. Edited by Walton Burns Interior and Cover Design by Red Panda Editorial Services Country of Manufacture Specified on Last Page First Printing 2021 Table of Contents Other Creative Writing Books by Alphabet Publishing ii Table of Contents v How to Use this Collection viii Section I - Monsters and Mysterious Creatures What Happened to the Dinosaurs? 2 The Loch Ness Monster 7 The Elusive Ivory-billed Woodpecker 13 Bigfoot: Ancient Ape of The Northwest 18 It’saBird?It’saPlane?It’saPicasso 23 Section II - Heroes and Villains Genghis Khan: Villain or Hero 31 The Children’s Crusade 37 Artist or Monster? Stop Adolf Hitler 44 Lyuh Woon-hyung and the Division of Korea 50 Who Killed Tupac? 55 Section III - Famous Unsolved Crimes and Criminals Who Was Jack the Ripper? 61 The Osage Indian Murders 67 D. -

Project #3: Inspired By… - Description Critique Date - 3/29/19 (Fri)

Project #3: Inspired by… - Description Critique Date - 3/29/19 (Fri) "The world is filled to suffocating. Man has placed his token on every stone. Every word, every image, is leased and mortgaged. We know that a picture is but a space in which a variety of images, none of them original, blend and clash." – Sherrie Levine Conceptual Requirements: In this project, you will do your best to interpret the style of a particular photographer who interests you. You will research them as well as their work in order to make photographs that have a signature aesthetic or approach that is specific to them, and also contribute your ideas. Technical Requirements: 1. Start with the list on the back of this page (the Project Description sheet), and start web searches for these photographers. All the ones listed are masters in their own right and a good starting point for you to begin your search. Select one and confirm your choice with me by the due date (see the syllabus). 2. After choosing a photographer, go on the web and to the library to check out books on them, read interviews, and look at every image you can that is made by them. Learn as much as you can and take notes on your sources. 3. Type your name, date, and “Project 3: Inspired by...” at the top of a Letter sized page. Then write a 2 page research paper on your chosen photographer. Be sure to include information such as where and when they were born, where it is that they did their work, what kind of camera and film formats they used, their own personal history, etc. -

Joan Fontcuberta

JOAN FONTCUBERTA Barcelona, 1955 INDIVIDUAL EXHIBITIONS 2013 Àngels barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. 2012 Orogénesis, photo edition berlin, Berlin. Deletrix, Nathalie Parienté, Paris. A través del Mirall, espai d’arts rocaumbert, Granollers. 2011 FAUNA. Museo Universitario del Chopo. MX. From here on. Atelier de Mécanique, Arles, Les Rencontres D’Arles, FR (co-curator). FAUNA. Museo Universitario del Chopo. MX. Frontal Nude i altres paisatges, Galeria Palma Dotze, Vilafranca del Penedès. A través del espejo, Centro Cultural Puertas de Castilla, Murcia. A través del espejo, Casa de la Moneda, Bogotá. 2010 Through the Looking Glass, Angels Barcelona. Orgénesis, Foam Fotografie Museum, Amsterdam. Resiliència, Galería Mayoral, Barcelona. A través del espejo, Galerías Xalapa, México. De Natura, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lille. 2009 Blow up Blow up, Galeria Àngels Barcelona. Blow Up Blow Up, Atelier de Forges, Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie, Arles. Datascapes, Djanogly Art Gallery, Nottingham. Datascapes, Usher Gallery, Lincoln. Googlegrams, Galeria Vanguardia, Bilbao. Googlegrams, Albury Regional Gallery, New South Wales, Austràlia. Googlegrams, Pinnacles Gallery, Riverway Arts Centre, Queensland, Australia. Hydropithèque, Musée-Chateau, Annecy. Landscapes without Memory, Reiss-Eingelhorn Museen, Mannheim. Santa Inocencia, Museo de Albarracín, Albarracín. 2008 De facto. Joan Fontcuberta. 1986 - 2008. Curator: Iván de la Nuez. Palau de la Virreina, Barcelona. Des monstres et des prodiges, Musée-Château, Annecy. Sputnik, Artothèque, Annecy. Sputnik, Musée Gassendi, Digne. Botánica oculta, Photomuseim, Zarautz. Googlegramas, Galerie Braunbehrens, Munich.cat. Googlegramas, Instituto Cervantes, Nápoles. Googlegramas, Instituto Cervantes, Pekín. Deconstructing Osama, Fundació Octubre, Valencia. Deconstructing Osama, Fundació La Caixa, Lleida. Tierras de nadie, Centro Cultural Miguel Castillejo, Jaén.cat. 2007 Perfida Imago, Musée d’Angers. Orogenesis, Bellas Artes Gallery, Santa Fe (Nuevo Méjico, EE.UU.). -

AVT 253: DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY I • T&Th 10:30 AM – 1:10 PM • ROOM L016 SYLLABUS – SPRING 2015

AVT 253: DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY I • T&Th 10:30 AM – 1:10 PM • ROOM L016 SYLLABUS – SPRING 2015 Professor: Jay Seawell [email protected] Office hours: By appointment either before or after class NOTE: THIS SYLLABUS IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE This class fulfills a General Education Core requirement for Arts. Core requirements help ensure that students become acquainted with the broad range of intellectual domains that contribute to a liberal education. By experiencing the subject matter and ways of knowing in a variety of fields, students will be better able to synthesize new knowledge, respond to fresh challenges, and meet the demands of a complex world. Arts goal: Courses aim to achieve a majority of the following learning outcomes: students will be able to identify and analyze the formal elements of a particular art form using vocabulary appropriate to that form; demonstrate an understanding of the relationship between artistic technique and the expression of a work’s underlying concept; analyze cultural productions using standards appropriate to the form and cultural context; analyze and interpret material or performance culture in its social, historical, and personal contexts; and engage in the artistic process, including conception, creation, and ongoing critical analysis. COURSE DESCRIPTION This class explores photography in a fine arts context. This class will introduce you to the artistic process, which involves learning technical skills, using problem solving and critical thinking while making images, and discussing and analyzing images, all of which are key components of making art. Each time an assignment is due, we will have a critique as a class so that you can receive constructive feedback from your peers and me. -

2019 27Th Annual Poets House Showcase Exhibition Catalog

2019 27th Annual Poets House Showcase Exhibition Catalog Poets House | 10 River Terrace | New York, NY 10282 | poetshouse.org ELCOME to the 2019 Poets House Showcase, our annual, all-inclusive exhibition of the most recent poetry books, chapbooks, broadsides, artists’ books, and multimedia works published in the United States and W abroad. This year marks the 27th anniversary of the Poets House Showcase and features over 3,300 books from more than 800 different presses and publishers. For 27 years, the Showcase has helped to keep our collection current and relevant, building one of the most extensive collections of poetry in our nation—an expansive record of the poetry of our time, freely available and open to all. Building the Exhibit and the Poets House Library Collection Every year, Poets House invites poets and publishers to participate in the annual Showcase by donating copies of poetry titles released since January of the previous year. This year’s exhibit highlights poetry titles published in 2018 and the first part of 2019. Books have been contributed by the entire poetry community, from the publishers who send on their titles as they’re released, to the poets who mail us signed copies of their newest books, to library visitors donating books when they visit us. Every newly published book is welcomed, appreciated, and featured in the Showcase. The Poets House Showcase is the mechanism through which we build our library: a comprehensive, inclusive collection of over 70,000 poetry works, all free and open to the public. To make it as extensive as possible, we reach out to as many poetry communities and producers as we can, bringing together poetic voices of all kinds to meet the different needs and interests of our many library patrons. -

Vnesheconombank Group Sustainability Report

Vnesheconombank Group Sustainability Report Vnesheconombank Group Sustainability Report 2013 VNESHECONOMBANK / Vnesheconombank Group Sustainability Report 2013 Contents About the Report ..............................................................................................................................................................................................4 Chairman’s Statement .................................................................................................................................................................................6 Vnesheconombank Group: Key Highlights ........................................................................................................................ 10 Highlights 2013 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 12 Vnesheconombank’s History ............................................................................................................................................................ 14 1. Vnesh econom bank’s Strategy ................................................................................................................................................. 16 1.1. Priority Business Lines ................................................................................................................................................................ 18 1.2. Strategy Implementation. Sustainability Objectives -

Nota Prensa FEITO FOTOGR Ing.Pdf

PRESS RELEASE “THE PHOTOGRAPHIC FACT. Photographic collection of the City Council of Vigo 1984-2000” DATES: 23rd of January- 21st of March 2004 VENUE: First floor exhibition rooms of the MARCO OPENING TIMES: Tuesday to Sunday (holidays included): from 11:00 to 21:00. CURATORS: Manuel Sendón and Xosé Luís Suárez Canal COORDINATOR: Iñaki Martínez Antelo PRODUCED BY: MARCO - Museo de Arte Contemporánea de Vigo ARTISTS EXHIBITED: 107 Xosé Abad (Galicia) Pere Formiguera (Spain) Roberto Ribao (Galicia) Xosé Luis Abalo (Galicia) Anna Fox (U.K.) Mar R. Caldas (Galicia) Michael Ackerman (USA) J. François Joly (France) Wojcieh Prazmowski Delmi Álvarez (Galicia) Xosé Gago (Galicia) (Poland) Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexico) Pepe Galovart (Galicia) Lalo R. Villar (Galicia) Arquivo Llanos (Galicia) Isabel García (Galicia) Pierre Radisic (Belgium) Arquivo Panateca (El Salvador) Antonio García Pereira (Galicia) Cristina Rodríguez (Galicia) Aziz+Cucher (USA) Flor Garduño (Mexico) Rubén Rguez. Torres Olivo Barbieri (Italy) Julian Germain (UK) (Galicia) Adolfo Barcia (Galicia) Mario Giacomelli (Italy) Arthur Rothstein (USA) José Ramón Bas (Spain) Claudia Gordillo (Nicaragua) America Sánchez (Spain) Gabriele Basilico (Italy) Rob Grierson (U.K.) Pablo Sánchez Corral John Benton-Harris (U.K.) Luis González Palma (Galicia) Nancy Burson (USA) (Guatemala) Schmid/Fricke (Germany) Ramón Caamaño (Galicia) Guido Guidi (Italy) Dagmar Sippel (Germany) Daniel Canogar (Spain) Amanda Harman (U.K.) Manuel Sonseca (Spain) Vari Caramés (Galicia) Iavicoli (Italy) Javier Teniente -

A Description of the Main Characters in the Movie the Greatest Showman

A DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE MOVIE THE GREATEST SHOWMAN A PAPER BY ELVA RAHMI REG.NO: 152202024 DIPLOMA III ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF CULTURE STUDY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH SUMATERA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I am ELVA RAHMI, declare that I am the sole author of this paper. Except where reference is made in the text of this paper, this paper contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a paper by which I have qualified for or awarded another degree. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of this paper. This paper has not been submitted for the award of another degree in any tertiary education. Signed : ……………. Date : 2018 i UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA COPYRIGHT DECLARATION Name: ELVA RAHMI Title of Paper: A DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE MOVIE THE GREATEST SHOWMAN. Qualification: D-III / Ahli Madya Study Program : English 1. I am willing that my paper should be available for reproduction at the discretion of the Libertarian of the Diploma III English Faculty of Culture Studies University of North Sumatera on the understanding that users are made aware of their obligation under law of the Republic of Indonesia. 2. I am not willing that my papers be made available for reproduction. Signed : ………….. Date : 2018 ii UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA ABSTRACT The title of this paper is DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE GREATEST SHOWMAN MOVIE. The purpose of this paper is to find the main character. -

Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction

Andrew May Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction Editorial Board Mark Alpert Philip Ball Gregory Benford Michael Brotherton Victor Callaghan Amnon H Eden Nick Kanas Geoffrey Landis Rudi Rucker Dirk Schulze-Makuch Ru€diger Vaas Ulrich Walter Stephen Webb Science and Fiction – A Springer Series This collection of entertaining and thought-provoking books will appeal equally to science buffs, scientists and science-fiction fans. It was born out of the recognition that scientific discovery and the creation of plausible fictional scenarios are often two sides of the same coin. Each relies on an understanding of the way the world works, coupled with the imaginative ability to invent new or alternative explanations—and even other worlds. Authored by practicing scientists as well as writers of hard science fiction, these books explore and exploit the borderlands between accepted science and its fictional counterpart. Uncovering mutual influences, promoting fruitful interaction, narrating and analyzing fictional scenarios, together they serve as a reaction vessel for inspired new ideas in science, technology, and beyond. Whether fiction, fact, or forever undecidable: the Springer Series “Science and Fiction” intends to go where no one has gone before! Its largely non-technical books take several different approaches. Journey with their authors as they • Indulge in science speculation—describing intriguing, plausible yet unproven ideas; • Exploit science fiction for educational purposes and as a means of promoting critical thinking; • Explore the interplay of science and science fiction—throughout the history of the genre and looking ahead; • Delve into related topics including, but not limited to: science as a creative process, the limits of science, interplay of literature and knowledge; • Tell fictional short stories built around well-defined scientific ideas, with a supplement summarizing the science underlying the plot. -

Geopolitics of Emerging and Disruptive Technologies

GEOPOLITICS OF EMERGING AND DISRUPTIVE TECHNOLOGIES 1 GEOPOLITICS OF EMERGING AND DISRUPTIVE TECHNOLOGIES Michał Rekowski, ToMasz PiekaRz, BaRBaRa szTokfisz, RoBert siudak, izaBela alBRychT, PRzeMysław Roguski, Paweł kosTkiewicz, Maciej siciaRek, kRzyszTof silicki, Magdalena wRzosek, ToMasz dylik, TeodoR BuchneR, joanna ŚwiąTkowska, andRea g. RodRíguez, kaMil Mikulski EDITORS: izaBela alBRychT, Michał Rekowski, kaMil Mikulski AUTHORS: Michał Rekowski TABle of conTenTS International Competition in the Digital Age Tomasz Piekarz Digital Technologies as an Element of Power Barbara Sztokfisz Cyberdiplomacy – a Tool for Building Digital Peace introduCTION ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 7 Robert Siudak New Entities in a Multilateral Cyber World Izabela Albrycht OPENING REMARKS ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 10 The Power of Digital Data Przemysław Roguski, PhD International competition IN The digital age ������������������������������������������ 13 The Geopolitics of Cloud Computing Paweł Kostkiewicz, Maciej Siciarek, Krzysztof Silicki, Magdalena Wrzosek, PhD digital technologies AS AN ELEMENT of power ������������������������������������������ 27 Certification and Standardisation in the Context of Digital Sovereignty Tomasz Dylik Cyberdiplomacy – a tool for BuILDING digital peace ����������������������������� 41 Geopolitics of Digital Belts and Roads Teodor Buchner, PhD NEW ENTITIES -

Introduction//012 Origins and Definitions//022 Conventions

Introduction//012 ORIGINS AND DEFINITIONS//022 CONVENTIONS//036 DOES DOCUMENTARY EXIST?//050 PHOTOJOURNALISM AND DOCUMENTARY: FOR, AGAINST AND BEYOND//078 ACTIVE AND PASSIVE SPECTATORS//116 THE LIMITS OF THE VISIBLE//150 DOCUMENTARY FICTIONS//178 COMMITMENT//198 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES//228 Bibliography//230 INDEX//234 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS//239 The immediate instruments are two: the motionless camera and the printed word. The governing instrument – which is also one of the centres of the subject – is individual, anti-authoritative human consciousness. James Agee, with Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, 1941 ORIGINS AND DEFINITIONS ACTIVE AND PASSIVE SPECTATORS Walter Benjamin Thirteen Theses Against Snobs, Susan Sontag On Photography, 1977//118 1928//024 Martha Rosler in, around, and afterthoughts Elizabeth McCausland Documentary Photography, (on documentary photography), 1981//122 1939//025 Ariella Azoulay Citizenship Beyond Sovereignty: James Agee, with Walker Evans Let Us Now Praise Towards a Redefinition of Spectatorship, 2008//130 Famous Men, 1941//029 Judith Butler Torture and the Ethics of Photography, John Grierson Postwar Patterns, 1946//030 2009//135 Hito Steyerl A Language of Practice, 2008//145 CONVENTIONS Philip Jones Griffiths The Curse of Colour, 2000//038 THE LIMITS OF THE VISIBLE An-My Lê Interview with Art21, 2007//042 Georges Didi-Huberman Images in Spite of All: David Goldblatt Interview with Mark Haworth-Booth, Four Photographs from Auschwitz, 2003//152 2005//047 Harun Farocki Reality Would Have to Begin, 2004//155 Lisa F. Jackson Interview with Melissa Silverstein, DOES DOCUMENTARY EXIST? 2008//163 Carl Plantinga What a Documentary Is, After All, Lisa F. Jackson Interview with Ben Kharakh, 2008//165 2005//052 Ursula Biemann Black Sea Files, 2005//168 Jacques Rancière Naked Image, Ostensive Image, Marta Zarzycka Showing Sounds: Listening to War Metamorphic Image, 2003//063 Photographs, 2012//171 Trinh T. -

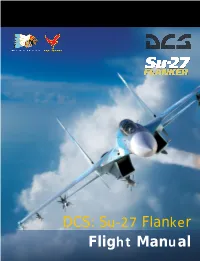

DCS: Su-27 Flanker Flight Manual

[SU-27] DCS DCS: Su-27 Flanker Eagle Dynamics i Flight Manual DCS [SU-27] DCS: Su-27 for DCS World The Su-27, NATO codename Flanker, is one of the pillars of modern-day Russian combat aviation. Built to counter the American F-15 Eagle, the Flanker is a twin-engine, supersonic, highly manoeuvrable air superiority fighter. The Flanker is equally capable of engaging targets well beyond visual range as it is in a dogfight given its amazing slow speed and high angle attack manoeuvrability. Using its radar and stealthy infrared search and track system, the Flanker can employ a wide array of radar and infrared guided missiles. The Flanker also includes a helmet-mounted sight that allows you to simply look at a target to lock it up! In addition to its powerful air-to-air capabilities, the Flanker can also be armed with bombs and unguided rockets to fulfil a secondary ground attack role. Su-27 for DCS World focuses on ease of use without complicated cockpit interaction, significantly reducing the learning curve. As such, Su-27 for DCS World features keyboard and joystick cockpit commands with a focus on the most mission critical of cockpit systems. General discussion forum: http://forums.eagle.ru ii [SU-27] DCS Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... VI SU-27 HISTORY ............................................................................................................. 2 ADVANCED FRONTLINE FIGHTER PROGRAMME .........................................................................