Speeches in Herodotus 5–9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Conflict in the Peloponnese

CONFLICT IN THE PELOPONNESE Social, Military and Intellectual Proceedings of the 2nd CSPS PG and Early Career Conference, University of Nottingham 22-24 March 2013 edited by Vasiliki BROUMA Kendell HEYDON CSPS Online Publications 4 2018 Published by the Centre for Spartan and Peloponnesian Studies (CSPS), School of Humanities, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK. © Centre for Spartan and Peloponnesian Studies and individual authors ISBN 978-0-9576620-2-5 This work is ‘Open Access’, published under a creative commons license which means that you are free to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form and that you in no way alter, transform or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without express permission of the authors and the publisher of this volume. Furthermore, for any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/csps TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................. i THE FAMILY AS THE INTERNAL ENEMY OF THE SPARTAN STATE ........................................ 1-23 Maciej Daszuta COMMEMORATING THE WAR DEAD IN ANCIENT SPARTA THE GYMNOPAIDIAI AND THE BATTLE OF HYSIAI .............................................................. 24-39 Elena Franchi PHILOTIMIA AND PHILONIKIA AT SPARTA ......................................................................... 40-69 Michele Lucchesi SLAVERY AS A POLITICAL PROBLEM DURING THE PELOPONESSIAN WARS ..................... 70-85 Bernat Montoya Rubio TYRTAEUS: THE SPARTAN POET FROM ATHENS SHIFTING IDENTITIES AS RHETORICAL STRATEGY IN LYCURGUS’ AGAINST LEOCRATES ................................................................................ 86-102 Eveline van Hilten-Rutten THE INFLUENCE OF THE KARNEIA ON WARFARE .......................................................... -

Solon 638-539 B.C

75 AD SOLON 638-539 B.C. Plutarch translated by John Dryden Plutarch (46-120) - Greek biographer, historian, and philosopher, sometimes known as the encyclopaedist of antiquity. He is most renowned for his series of character studies, arranged mostly in pairs, known as “Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans” or “Parallel Lives.” Solon (75 AD) - A study of the life of the Athenian lawgiver, Solon. SOLON DIDYMUS, the grammarian, in his answer to Asclepiades concerning Solon’s Tables of Law, mentions a passage of one Philocles, who states that Solon’s father’s name was Euphorion, contrary to the opinion of all others who have written concerning him; for they generally agree that he was the son of Execestides, a man of moderate wealth and power in the city, but of a most noble stock, being descended from Codrus; his mother, as Heraclides Ponticus affirms, was cousin to Pisistratus’s mother, and the two at first were great friends, partly because they were akin, and partly because of Pisistratus’s noble qualities and beauty. And they say Solon loved him; and that is the reason, I suppose, that when afterwards they differed about the government, their enmity never produced any hot and violent passion, they remembered their old kindnesses, and retained “Still in its embers living the strong fire” of their love and dear affection. For that Solon was not proof against beauty, nor of courage to stand up to passion and meet it “Hand to hand as in the ring,” we may conjecture by his poems, and one of his laws, in which there are practices forbidden to slaves, which he would appear, therefore, to recommend to freemen. -

Plutarch's Lives of Greek Heroes

V e p»>'e'.tt'"''''v-' -'sr.«'*:©?»e«4 gC'^S'*'^"''^"' joYin M. Kelly iWjnong Donated by William Klassen and Dona Hafioey The Uaiuefisity of St. MicbaeJ's College Toronto, Onton\o elrvv*^ DlacKie's Library of Famoxis DooKs Louisa M. Alcott. Good Wives. Little Women. abbey. Jane Austen. northanger R. M. Ballantyne. Coral Island. Martin Rattler. Ungava. the Wager, The Hon. John Byron. Wreck of Did. Susan Coolidge. What Katy What Katy Did at School. What Katy Did Next. Deerslayer. J. Fenimore Cooper. Ned Myers. The Pathfinder. Maria S. Cummins. The Lamplighter. R. H. Dana. Two Years Before the Mast. Daniel Defoe. Robinson Crusoe. Maria Edgeworth. The Good Governess. Moral Tales. Benjamin Franklin. Autobiography Oliver Goldsmith. The Vicar of Wakefield. Mrs. Gore. The Snowstorm. Captain Basil Hall. The Log-Book of a Midshipman. Charles Kingsley. The Heroes. W. H. G. Kingston. Peter the Whaler. Manco, the Peruvian^Qhief. Charles Lamb. Talbs from Sha^i?peaSe.U','^x Lord Macaulay. Essays on EngIkh Hiffr<»;Y.~ Ci^.' Captain Marryat. Children of., the New FoRE^.y-\ MaSTERMAN REAE^.^J ||5i3?OY ^ Poor Jack. Settlers in Catijada. Harriet Martineav'. Feats on the Fiord. Herman Melville. Typee, a Romance of the South Seas. Mary Russell Mitford. Selections from Our Village. Country Sketches. Peter Parley. Tales about Greece and Rome. Edgar Allan Poe. Tales of Romance and Fantasy. Mayne Reid. The Rifle Rangers. Cristoph von Schmid. The Basket of Flowers. Michael Scott. The Cruise of the Midge. Tom Cringle's Log. Sir Walter Scott. A Legend of Montrose. The Story of Prince Charlie. The Downfall of Napoleon. -

HERODOTUS I I I 1 IV I I BOOKS VIII-IX I I I I L I I I I I I 1 I 1 I L I 1 I 1 I I I I L G Translated by I a D

I I 1 I 1 OEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY I i I 1 I I I m HERODOTUS I i I 1 IV i I BOOKS VIII-IX I i i I l I I I I i i 1 I 1 i l i 1 i 1 I I i I l g Translated by i A D. GODLEY i i I 1 I I iN Complete list of Lock titles can be V*o Jound at the end of each volume the historian HERODOTUS grc-at Greek was born about 484 B.C., at Halicar- nassus in Caria, Asia Minor, when it was subject to the Persians. He travelled in of Asia widely most Minor, Egypt (as as far Assuan), North Africa, Syria, the country north of the Black Sea, and many parts of the Aegean Sea and the mainland of Greece. He lived, it seems, for some time in Athens, and in 443 went with other colonists to the new city Thurii (in he died about South Italy) where 430 B.C. He was 'the prose correlative of the bard, a narrator of the deeds of real men, and a describer of foreign places' (Murray). His famous history of warfare between the Greeks and the Persians has an epic enhances his dignity which delightful style. It includes the rise of the Persian power and an account of the Persian the empire ; description of Egypt fills one book; because Darius attacked Scythia, the geography and customs of that land are also even in the later books on the given ; the Persians attacks of against Greece there are digressions.o All is most entertainingo a After and produces grand unity. -

Military Death and Cowardice in Sparta Biblioteka Narodow a Warszawa

Ryszard Kulesza “With the shield or upon it”. Military death and cowardice in Sparta Biblioteka Narodow a Warszawa 30001012793202 Tll. &3M. Vb/I Akme. Studia histórica 2/2008 ISBN 978-83-904596-9-2 Druk i oprawa: Zakład Graficzny UW, zam. 249/08 Sparta is often portrayed as a military society, and her atti tudes to valour and cowardice at first sight appear to support this perception. However, when one looks more closely at the treatment of cowards1, matters appear less clear-cut in several respects and suggest that the “win or die” mentality was a guideline rather than an all-encompassing requirement. Closely linked with the issue of valour is the problem of cowardice, as it is explained by Xenophons remark: “He [sc. Lycurgus] made it clear that happiness was the reward of the 1 After the publication o f the detailed study on the tresantes by J. Ducat (The Spartan 'tremblers [in:] S. Hodkinson, A. Powell (ed.), Sparta an d War, The Classical Press o f Wales 2006, pp. 1-55), it may seem a waste o f the authors’, and especially of the readres’ time to publish other studies devoted to the same topic. The main body o f this article was written before Ducats text appeared. It has, obviously, taken me a long time to decide whether further work on this makes any sense; finally, having read some other studies devoted to Sparta, I have decided that it is not necessarily reasonable to resign from all attempts to formulate new thoughts on an issue after an outstanding study on it has appeared. -

The Greek Histories

The Greek Histories Old Western Culture Reader Vol. 3 The Greek Histories Old Western Culture Reader Vol. 3 Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon Companion to Greeks: The Histories, a great books curriculum by Roman Roads Media. The Greek Histories: Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon Old Western Culture Reader, Volume 3. Copyright © 2018 Roman Roads Media Published by Roman Roads Media, LLC 121 E 3rd St., Moscow ID 83843 www.romanroadsmedia.com [email protected] Editor: Evan Gunn Wilson Series Editor: Daniel Foucachon Cover Design: Valerie Anne Bost and Rachel Rosales Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher, except as provided by the USA copyright law. Version 1.0.0 The Greek Histories: Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon Old Western Culture Reader Vol. 3 Roman Roads Media, LLC. ISBN: 978-1-944482-33-6 This is a companion reader for the Old Western Culture curriculum by Roman Roads Media. To find out more about this course, visit www.romanroadsmedia.com Old Western Culture Great Books Reader Series THE GREEKS The Epics Drama & Lyric The Histories The Philosophers THE ROMANS The Aeneid The Historians Early Christianity Nicene Christianity CHRISTENDOM Early Medievals Defense of the Faith The Medieval Mind The Reformation EARLY MODERNS Rise of England The Enlightenment The Victorian Poets The Novels Copyright © 2018 by Roman Roads Media, LLC Roman Roads Media 121 E 3rd St Moscow, Idaho 83843 www.romanroadsmedia.com Roman Roads combines its technical expertise with the experience of established authorities in the field of classical education to create quality video courses and resources tailored to the homeschooler. -

Pushing the Boundaries of Myth: Transformations of Ancient Border

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PUSHING THE BOUNDARIES OF MYTH: TRANSFORMATIONS OF ANCIENT BORDER WARS IN ARCHAIC AND CLASSICAL GREECE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS: ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN WORLD BY NATASHA BERSHADSKY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2013 UMI Number: 3557392 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3557392 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee, Jonathan Hall, Christopher Faraone, Gloria Ferrari Pinney and Laura Slatkin, whose ideas and advice guided me throughout this research. Jonathan Hall’s energy and support were crucial in spurring the project toward completion. My identity as a classicist was formed under the influence of Gregory Nagy. I would like to thank him for the inspiration and encouragement he has given me throughout the years. Daniela Helbig’s assistance was invaluable at the finishing stage of the dissertation. I also thank my dear colleague-friends Anna Bonifazi, David Elmer, Valeria Segueenkova, Olga Levaniouk and Alexander Nikolaev for illuminating discussions, and Mira Bernstein, Jonah Friedman and Rita Lenane for their help. -

The Harvard Classics Eboxed

HARVARD LASSICS THEFIVE-FOOT HELFOFBOOKS OSES BUS I S3 ESI Dais MM THE HARVARD CLASSICS The Five-Foot Shelf of Books I s I THE HARVARD CLASSICS EDITED BY CHARLES W. ELIOT, LL.D. Plutarch's Lives of Themistocles • Pericles • Aristides Alcibiades and Coriolanus Demosthenes and Cicero Caesar and Antony IN THE TRANSLATION CALLED DRYDEn's CORRECTED AND REVISED BY ARTHUR HUGH CLOUGH With Introductions and No/« \olume 12 P. F. Collier & Son Corporation NEW YORK Copyright, 1909 By P. F. Collier & Son MANUFACTURED IN U. S. A. CONTENTS PACE Themistocles 5 Pericles 35 Aristides 78 Alcibiades 106 coriolanus 147 Comparison of Alcibiades with Coriolanus 186 Demosthenes 191 Cicero 218 Comparison of Demosthenes and Cicero 260 Cesar 264 Antony 322 INTRODUCTORY NOTE Plutarch, the great biographer of antiquity, had not the fortune him- self to find a biographer. For the facts of his life we are dependent wholly upon the fragmentary information that he scattered casually throughout his writings. From these we learn that he was born in the small Boeotian town of Chaeroneia in Greece, between 46 and 51 A. D., of a family of good standing and long residence there; that he married a certain Timoxena, to whom he wrote a tender letter of consolation on the death of their daughter; and that he had four sons, to two of whom he dedicated one of his philosophical treatises. He began the study of philosophy at Athens, travelled to Alexandria and in various parts of Italy, and sojourned for a considerable period in Rome; but he seems to have continued to regard Chaeroneia as his home, and here he did a large part of his writing and took his share in public service. -

Herodotus Book Ix

HERODOTUS BOOK IX MICHAEL A. FLOWER Franklin & Marshall College JOHN MARINCOLA New York University The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge ,UK West thStreet, New York, -, USA Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, , Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on , Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town , SouthAfrica http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typefaces Baskerville / pt and New Hellenic System LATEX ε [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Herodotus [History. Book ] Herodotus. Book IX / edited by Michael A. Flower and John Marincola. p. cm. – (Cambridge Greek and Latin classics) Includes bibliographical references and index. (pbk.) . Plataea, Battle of, . I. Flower, Michael A. II. Marincola, John. III. Series. . . –dc hardback paperback CONTENTS List of maps and figures page viii Preface ix Acknowledgements xii List of abbreviations xiii Introduction Life and times Narrative manner and technique Characterisation Historicalmethods and sources The battles of Plataea and Mycale Themes Dialect Manuscripts HRODOTOU ISTORIWN I Commentary Appendixes A Simonides’ poem on Plataea B Dedication of the seer Teisamenus? C The ‘Oath of Plataea’ D Battle Lines of the Greek and Persian armies at Plataea Bibliography Indexes vii MAPS . Plataea page . Samos and Mycale . Battle of Mycale FIGURES . Family tree of Pausanias page . -

AH 1.3 Politics and Society of Ancient Sparta Maria Preztler

JACT Teachers’ Notes AH 1.3 Politics and Society of Ancient Sparta Maria Preztler 1.Introduction ............................................................................................................... 2 1.1. Books and resources ...................................................................................... 2 1.1.1. Annotated list of books cited in the notes .......................................... 2 1.2. Introduction to the sources ............................................................................. 4 1.2.1. Tyrtaeus .............................................................................................. 4 1.2.2. Herodotus ........................................................................................... 5 1.2.3. Thucydides ......................................................................................... 5 1.2.4. Aristophanes ...................................................................................... 6 1.2.5. Xenophon ........................................................................................... 6 1.2.6. Plutarch .............................................................................................. 7 1.2.7. Other sources ..................................................................................... 7 1.3. Background Information ................................................................................ 8 1.3.1. Chronological Overview .................................................................... 8 2. Notes on the Specification Bullet Points -

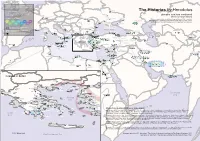

The Histories by Herodotus Chapter, a Hexagon with Light Border Is Drawn Near the Location the Character Hylaea Comes From

For each location mentioned in a chapter, a hexagon with dark border is drawn near that location. Dnieper For each character mentioned in a Gelonus The Histories by Herodotus chapter, a hexagon with light border is drawn near the location the character Hylaea comes from. placable locations mentioned Celts Danube Pyrene three or more times Chapter Color Scale: Gerrians Carpathian Mountains Tanaïs Where a region is dominated by a large settlement (like a capital), Far Scythia the settlement is generally used instead of the region to save space. I III V VII IX Some names in crowded locations on the map have been left out. Dacia Tyras Borysthenes II IV VI VIII Cremnoi Istros the place or the people was Illyria Scythian Neapolis mentioned explicitly Getae Marseille Odrysians Black Sea a character from nearby was Aléria Italy Mesambria Caucasus Massagetae Phasis mentioned Paeonia Sinop Pteria Caere Brygians Apollonia city or mountain location Mt. Haemus Caspian Byzantium Colchis Sea Sardinia Taranto Thyrea Sogdia Siris Velia Messapii Terme River Cyzicus Gordium Sybaris Crotone Cappadocia Sardis Armenia Messina Segesta Rhegium Greece Tigris Caspiane Tartessos Gela Pamphylia Parthia Carthage Selinunte Syracuse Milas Kaunos Cilicia Telmessos Nineveh Kamarina Lindos Posideion Xanthos Salamis Euphrates Kourion Ecbatana Amathus Gandhara Cyprus Tyre Sidon Cyrene Lotophagi Babylon Susa Barca Garamantes Macai Saïs Ienysos Heliopolis Petra Atlas Persepolis Asbystai Awjila Memphis Ammonians Egyptian Thebes Greece in detail Elephantine BC invasion b Myrkinos 480 y Xe rxes Red Macedonia Abdera Cicones Eïon Doriscus Sea Therma The Nile Olynthus Akanthos Thasos Cardia Sestos Pieria Vardar Samothrace Lampsacus Chalcidice Sane Imbros Abydos Pindus Mt.