Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discover the Styles and Techniques of French Master Carvers and Gilders

LOUIS STYLE rench rames F 1610–1792F SEPTEMBER 15, 2015–JANUARY 3, 2016 What makes a frame French? Discover the styles and techniques of French master carvers and gilders. This magnificent frame, a work of art in its own right, weighing 297 pounds, exemplifies French style under Louis XV (reigned 1723–1774). Fashioned by an unknown designer, perhaps after designs by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (French, 1695–1750), and several specialist craftsmen in Paris about 1740, it was commissioned by Gabriel Bernard de Rieux, a powerful French legal official, to accentuate his exceptionally large pastel portrait and its heavy sheet of protective glass. On this grand scale, the sweeping contours and luxuriously carved ornaments in the corners and at the center of each side achieve the thrilling effect of sculpture. At the top, a spectacular cartouche between festoons of flowers surmounted by a plume of foliage contains attributes symbolizing the fair judgment of the sitter: justice (represented by a scale and a book of laws) and prudence (a snake and a mirror). PA.205 The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust LOUIS STYLE rench rames F 1610–1792F Frames are essential to the presentation of paintings. They protect the image and permit its attachment to the wall. Through the powerful combination of form and finish, frames profoundly enhance (or detract) from a painting’s visual impact. The early 1600s through the 1700s was a golden age for frame making in Paris during which functional surrounds for paintings became expressions of artistry, innovation, taste, and wealth. The primary stylistic trendsetter was the sovereign, whose desire for increas- ingly opulent forms of display spurred the creative Fig. -

Download (3104Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/59427 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. THESIS INTRODUCTION The picture of themselves which the Victorians have handed down to us is of a people who valued morality and respectability, and, perhaps, valued the appearance of it as much as the reality. Perhaps the pursuit of the latter furthered the achievement of the former. They also valued the technological achievements and the revolution in mobility that they witnessed and substantially brought about. Not least did they value the imperial power, formal and informal, that they came to wield over vast tracts of the globe. The intention of the following study is to take these three broad themes which, in the national consciousness, are synonymous with the Victorian age, and examine their applicability to the contemporary theatre, its practitioners, and its audiences. Any capacity to undertake such an investigation rests on the reading for a Bachelor’s degree in History at Warwick, obtained when the University was still abuilding, and an innate if undisciplined attachment to things theatrical, fostered by an elder brother and sister. Such an attachment, to those who share it, will require no elaboration. My special interest will lie in observing how a given theme operated at a particular or local level. -

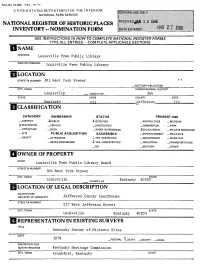

State Historic Preservation Officer Certification the Evaluated Significance of This Property Within the State Is

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ NAME HISTORIC Louisville Free Public Library AND/OR COMMON Louisville Free public Library LOCATION STREET&NUMBER 301 West York Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN " . , " , CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Louisville . .VICINITY OF 3&4 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Kentucky 021 llMll.'Jeff«r5»rvn 111 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT -XPUBLIC X.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM ^BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS .^EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS J-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED .X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL -^TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Louisville Free Public Library Board STREET & NUMBER 301 West York Street STATE CITY, TOWN Louisville VICINITY OF Kentucky 40203 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, » REGISTRY OF DEEDS; ETC. Jefferson County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER 517 West Jefferson Street CITY, TOWN STATE Louisville Kentucky 40203 TITLE Kentucky Survey of Historic Sites DATE 1978 —FEDERAL <LsTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Kentucky Heritage Commission CITY, TOWN Frankfort, Kentucky STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE -

Copyrighted Material

14_464333_bindex.qxd 10/13/05 2:09 PM Page 429 Index Abacus, 12, 29 Architectura, 130 Balustrades, 141 Sheraton, 331–332 Abbots Palace, 336 Architectural standards, 334 Baroque, 164 Victorian, 407–408 Académie de France, 284 Architectural style, 58 iron, 208 William and Mary, 220–221 Académie des Beaux-Arts, 334 Architectural treatises, Banquet, 132 Beeswax, use of, 8 Academy of Architecture Renaissance, 91–92 Banqueting House, 130 Bélanger, François-Joseph, 335, (France), 172, 283, 305, Architecture. See also Interior Barbet, Jean, 180, 205 337, 339, 343 384 architecture Baroque style, 152–153 Belton, 206 Academy of Fine Arts, 334 Egyptian, 3–8 characteristics of, 253 Belvoir Castle, 398 Act of Settlement, 247 Greek, 28–32 Barrel vault ceilings, 104, 176 Benches, Medieval, 85, 87 Adam, James, 305 interior, viii Bar tracery, 78 Beningbrough Hall, 196–198, Adam, John, 318 Neoclassic, 285 Bauhaus, 393 202, 205–206 Adam, Robert, viii, 196, 278, relationship to furniture Beam ceilings Bérain, Jean, 205, 226–227, 285, 304–305, 307, design, 83 Egyptian, 12–13 246 315–316, 321, 332 Renaissance, 91–92 Beamed ceilings Bergère, 240, 298 Adam furniture, 322–324 Architecture (de Vriese), 133 Baroque, 182 Bernini, Gianlorenzo, 155 Aedicular arrangements, 58 Architecture françoise (Blondel), Egyptian, 12-13 Bienséance, 244 Aeolians, 26–27 284 Renaissance, 104, 121, 133 Bishop’s Palace, 71 Age of Enlightenment, 283 Architrave-cornice, 260 Beams Black, Adam, 329 Age of Walnut, 210 Architrave moldings, 260 exposed, 81 Blenheim Palace, 197, 206 Aisle construction, Medieval, 73 Architraves, 29, 205 Medieval, 73, 75 Blicking Hall, 138–139 Akroter, 357 Arcuated construction, 46 Beard, Geoffrey, 206 Blind tracery, 84 Alae, 48 Armchairs. -

Antique English Empire Console Writing Side Table 19Th C

anticSwiss 02/10/2021 08:28:16 http://www.anticswiss.com Antique English Empire Console Writing Side Table 19th C FOR SALE ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 19° secolo - 1800 Regent Antiques London Style: Altri stili +44 2088099605 447836294074 Height:73cm Width:60cm Depth:40cm Price:2250€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: This is a beautiful small antique English Empire Gonçalo Alves console with integral writing slide and pen drawer, circa 1820 in date. This dual purpose table has a drawer above a pair of elegant tapering columns with gilded mounts to the top and bottom, behind them is a pair of rectangular columns framing a framed fabric slide that lifts up when required. This screen serves as a modesty / privacy screen. This piece has a single drawer with a writing slide with its original olive green leather writing surface over a pen drawer that can be pulled out from the side of the drawer whilst the writing surface is in use. This gorgeous console table will instantly enhance the style of one special room in your home and is sure to receive the maximum amount of attention wherever it is placed. Condition: In excellent condition having been beautifully restored in our workshops, please see photos for confirmation. Dimensions in cm: Height 73 x Width 60 x Depth 40 Dimensions in inches: Height 28.7 x Width 23.6 x Depth 15.7 Empire style, is an early-19th-century design movement in architecture, furniture, other decorative arts, and the visual arts followed in Europe and America until around 1830. 1 / 3 anticSwiss 02/10/2021 08:28:16 http://www.anticswiss.com The style originated in and takes its name from the rule of Napoleon I in the First French Empire, where it was intended to idealize Napoleon's leadership and the French state. -

How to Paint Black Furniture-A Dozen Examples of Exceptional Black Painted Furniture

How To Paint Black Furniture-A Dozen Examples Of Exceptional Black Painted Furniture frenchstyleauthority.com /archives/how-to-paint-black-furniture-a-dozen-examples-of-exceptional-black- painted-furniture Black furniture has been one of the most popular furniture paint colors in history, and a close second is white. Today, no other color comes close to these two basic colors which always seem to be a public favorite. No matter what the style is, black paint has been fashionable choice for French furniture,and also for primitive early American, regency and modern furniture. While the color of the furniture the same, the surrounds of these distinct styles are polar opposite requiring a different finish application. Early American furniture is often shown with distressing around the edges. Wear and tear is found surrounding the feet of the furniture, and commonly in the areas around the handles, and corners of the cabinets or commodes. It is common to see undertones of a different shade of paint. Red, burnt orange are common colors seen under furniture pieces. Furniture made from different woods, are often painted a color similar to wood color to disguise the fact that it was made from various woods. Paint during this time was quite thin, making it easily naturally distressed over time. – Black-painted Queen Anne Tilt-top Birdcage Tea Table $3,000 Connecticut, early 18th century, early surface of black paint over earlier red Joseph Spinale Furniture is one of the best examples to look at for painting ideas for early American furniture. This primitive farmhouse kitchen cupboard is heavily distressed with black paint. -

Hampshire Industrial Archaeology Society, Journal No. 21, 2013, Part 1

ISSN 2043-0663 Hampshire Industrial Archaeology Society Journal No. 21 (2013) www.hias.org.uk from Downloaded www.hias.org.uk from Front cover picture: The restored auditorium of the Kings Theatre, Southsea. (Ron Hasker) [see page 3] Back cover pictures: Top: Postcard view of Netley Hospital from the pier, with the dome of the chapel (still extant) dominating the centre. (Jeff Pain) [see page 9] Downloaded Bottom right: The lantern of J. E. Webb’s patent sewer gas destructor lamp in The Square, Winchester. (J. M. Gregory) [see page 14] Bottom left: 22 000 lb (10 tonne) Grand Slam bomb case on display at the Yorkshire Air Museum, Elvington. (Richard Hall) [see page 24] 1 Hampshire Industrial Archaeology Society (formerly Southampton University Industrial Archaeology Group) Journal No. 21, 2013 _________________________________________________________________ Contents Editorial ………………………..……………………………………………………………..1 The Contributors and Acknowledgements……………………………………………………2 The Kings Theatre, Southsea Ron Hasker .. …………………………….………………………………………….3 Netley Hospital 1855-1915 Jeff Pain …………………………………………………………………………. 8 Winchester’s Gas supply Martin Gregory ………………………………………………………………..…...13 Ashley Walk Bombing Range Richard Hall .…………………………………………………………………… …21 Editorial Welcome to Issue 21 of our Journal as we set out on our third decade. As usual, we have tried to include articles on a variety of subject areas in Industrial Archaeologywww.hias.org.uk in Hampshire. Our first article is on the Kings Theatre Southsea. Many of our provincial theatres have been lost in the last fifty years. Ron Hasker has provided a short history of the theatre and its construction and has chronicled its rebirth under the management of a local Trust. The restoration has retained most of the original features. -

Useful Information Why Cycle?

FAMOUS FIGURES CYCLE RIDE CYCLE TRAILS 7.5 mil e/ 12 km The famous people cycle ride takes FAMOUS FIGURES you on a tour to uncover some of CYCLE RIDE Portsmouth’s famous inhabitants of 7.5 mil e/ 12 km the past. The ride is 7.5 miles long. Detour A Highland Road Cemetery – the final resting place for Portsmouth Visitor Information Service From famous figures from history such as Nelson many interesting and distinguished names from Portsmouth’s past including many servicemen and women Why Cycle? We have two centres in Portsmouth. One is by the entrance to the and Henry VIII to some literary giants, famous as well as 8 holders of the Victoria Cross, associates of Historic Dockyard and the other is on the seafront next to the Blue engineers and architects – not to mention a 20th Charles Dickens and even Royalty. Whether you live in the area or not you may be surprised what Reef Aquarium. We offer a range of services including: information the landscape reveals to you. century comedian and actor, this ride will open on local attractions, events, entertainment and transport; discount tickets and vouchers for local attractions; accommodation your eyes to some of the many famous people Cycling lets you explore at your own pace – you can stop and admire the view, watch the birds, have a picnic or take photos. bookings; sale of local gifts, maps and publications; local theatre with Portsmouth connections. Detour B bookings. We are open 7 days a week 9:30am-5:15pm. (Closed Regular cycling can help you increase your fitness levels Christmas Day and Boxing Day, Southsea closed Wed and Thurs Old Portsmouth – this area covers 800 years of history from November to February). -

Bateman's Row by Kevin Moore

At the Heart of Hackney since 1967 2011 THE HACKNEY SOCIETY SPACENews and views about Hackney’s built Senvironment Issue 33 Summer 2011 Bateman’s Row By Kevin Moore I first came across the architect couple showing this to be a finely crafted and with our praise. It also received a Hackney Soraya Khan and Patrick Theis in 1999 considered building. Design Award. when I asked them to renovate my own The corner of Bateman’s Row and French View this building at night from Shoreditch house. They were keen to create a kitchen Place is outside the South Shoreditch High Street, looking up towards Kingsland in the basement, but less excited about Conservation Area. I only wish there were Road. It encapsulates exactly what is the prospect of renovating an entire listed more new buildings of this quality within it. meant by a contextual building within the building. Wanting a single contractor, I existing cityscape. The building is dark took them out of the equation. Big Mistake! Of the building the RIBA said: ‘In its and solid at the bottom and lights up to a Bateman’s Row is a remarkable building response to its surroundings, its scale and floating, glazed open top. It also has solar reminiscent of a Le Corbusier villa, recalling its mix of uses, this development defines panels, a green roof and natural ventilation. that period of heroic modernism. The a vision for the future of Shoreditch. It The lucky owners also have a generous top interior with dark, deep corners, numerous provides an environment for family-living floor roof terrace. -

Ze Studiów Nad Recepcją Problemów Architektury Między Neoklasycyzmem I Historyzmem W Sztuce Krajów Nordyckich XIX Wieku

NAUKA SCIENCE Zdzisława i Tomasz Tołłoczko* Ze studiów nad recepcją problemów architektury między neoklasycyzmem i historyzmem w sztuce krajów nordyckich XIX wieku The studies on reception of architectural problems between neoclassicism and historicism in the art of Nordic countries in the 19th century Słowa kluczowe: Dania, Norwegia, Szwecja, Finlandia, Key words: Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, historia architektury i urbanistyki, klasycyzm, empire, history of architecture and urban design, classicism, narodowy romantyzm, neogotyk, neorenesans, neobarok, empire, national romanticism, neo-Gothic, styl ok. 1900 neo-Renaissance, neo-Baroque, style around 1900 Rozwój architektury w Skandynawii w dziewiętnastym The development of architecture in Scandinavia in the stuleciu przebiegał w ogólnym zarysie podobnie jak w innych nineteenth century in general outline followed the same course państwach europejskich, atoli w krajach nordyckich neoklasy- as in other European countries, however in the Nordic coun- cyzm był na tym obszarze szczególnie stylem preferowanym. tries neoclassicism was the particularly preferred style. Political Polityczne przemiany, które wstrząsnęły fundamentami ancien changes which shook the foundations of ancien régime in the régime’u w czasie efemerycznego cesarstwa zbudowanego przez times of the ephemeral empire built by Emperor Napoleon I, cesarza Napoleona I, miały marginalne znaczenie dla rozwoju were of marginal signifi cance to the development of art in the sztuki na obszarze Danii, Szwecji i Norwegii. Pozostawała territories of Denmark, Sweden and Norway. Scandinavia re- przeto Skandynawia poza głównym obszarem teatru wojen na- mained outside the main theatre of Napoleonic wars, although poleońskich, aczkolwiek owe brzemienne w skutkach polityczne those political events fraught with consequences did not com- wydarzenia nie ominęły również monarchii nordyckich. -

HERITAGE NETWORK Specialists in Archaeology and the Historic Environment Since 1992

HERITAGE NETWORK Specialists in Archaeology and the Historic Environment Since 1992 Accredited Contractor Constructionline SEVENTH DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH 381 Holloway Road, LB Islington HN1234 DESK-BASED ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Page left blank to optimize duplex printing HERITAGE NETWORK Registered with the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists Managing Director: David Hillelson, BA MCIfA SEVENTH DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH, 381 Holloway Road, LB Islington Heritage Network ref.: HN1234 Desk-based Archaeological Assessment Prepared on behalf of Seventh Day Adventist Church, Holloway by Helen Ashworth BA ACIfA Report no. 967 November 2015 © The Heritage Network Ltd 111111 FFFURMSTON CCCOURT ,,, IIICKNIELD WAYAYAY ,,, LLLETCHWORTH ,,, HHHERTS ... SG6 1UJ TTTELEPHONE ::: (((01462)(01462) 685991 FFFAXAXAX ::: (01462) 685998 Page left blank to optimize duplex printing SDA Church, Holloway Road Desk-based Archaeological Assessment Contents Summary ......................................................................................................................... Page i Section 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... Page 1 Section 2 Baseline Data .................................................................................................................. Page 3 Section 3 Risk, Significance & Impact Assessments ..................................................................... Page 11 Section 4 Sources Consulted ........................................................................................................ -

Literary-Sites.Pdf

Whether you're an armchair traveler or road trip warrior, join us on a journey through America to visit homes, restaurants, bookshops, hotels, schools, museums, memorials and the occasional monument linked to some of our nation's Jewish authors. Along the way you'll gain insight into how these celebrated-and not so celebrated-writers lived and wrote. NEW YORK, NY Built in 1902, the Algonquin Hotel still famous exchanges: for example, Noel friend, Frederik Pohl, writes of how stands in all its Edwardian elegance at Coward’s compliment to Ferber on her Isaac’s father tried to prevent him from 59 West 44th Street. In its restaurant, new suit. “You look almost like a man,” reading pulp fiction sold in the store be beyond the signature oak-paneled lobby, he said, to which Ferber replied, “So do cause it would interfere with his school is a replica of the celebrated Round Table you.” Kevin Fitzpatrick, a Dorothy Parker work, but Isaac convinced him that a pe at which, from 1919 to 1929, a group researcher, leads walking tours devoted riodical such as Amazing Stories was fine, of sharp-tongued 20-somethings came to Round Table members; download the because, although fiction, it was “sci together for food, drink (no alcohol in schedule at dorothyparker.com. Show ence.” Asimov’s Foundation and Robot se the Prohibition years) and repartee. The Algonquin’s management a published ries are said to have inspired Gene Rod- daily gathering purportedly got its start work or one in progress and receive a denberry’s Star Trek.