“From Doubt and Decline Towards Dialogue: Discussing Anselm's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can We Prove God's Existence?

This transcript accompanies the Cambridge in your Classroom video on ‘Can we prove God’s existence?’. For more information about this video, or the series, visit https://www.divinity.cam.ac.uk/study-here/open-days/cambridge-your-classroom Can we prove God’s existence? Professor Catherine Pickstock Faculty of Divinity One argument to prove God’s existence In front of me is an amazing manuscript, is known as the ‘ontological argument’ — called the Proslogion, written nearly 1,000 an argument which, by reason alone – years ago by an Italian Benedictine monk proves that, the very idea of God as a called Anselm. perfect being means that God must exist, that his non-existence would be Anselm went on to become Archbishop of contradictory. Canterbury in 1093, and this manuscript is now kept in the University Library in These kinds of a priori arguments rely on Cambridge. logical deduction, rather than something one has observed or experienced: you It is an exploration of how we can know might be familiar with Kant’s examples: God, written in the form of a prayer, in Latin. Even in translation, it can sound “All bachelors are unmarried men. quite complicated to our modern ears, but Squares have four equal sides. All listen carefully to some of his words here objects occupy space.” translated from Chapters 2 and 3. I am Catherine Pickstock and I teach “If that, than which nothing greater can be Philosophy of Religion at the University of conceived, exists in the understanding Cambridge. And I am interested in how alone, the very being, than which nothing we can know the unknowable, and often greater can be conceived, is one, than look to earlier ways in which thinkers which a greater cannot be conceived. -

Online Library of Liberty: the Dialogues of Plato, Vol. 1

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Plato, The Dialogues of Plato, vol. 1 [387 AD] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

Anselm's Cur Deus Homo

Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo: A Meditation from the Point of View of the Sinner Gene Fendt Elements in Anselm's Cur Deus Homo point quite differently from the usual view of it as the locus classicus for a theory of Incarnation and Atonement which exhibits Christ as providing the substitutive revenging satisfaction for the infinite dishonor God suffers at the sin of Adam. This meditation will attempt to bring out how the rhetorical ergon of the work upon faith and conscience drives the sinner to see the necessity of the marriage of human with divine natures offered in Christ and how that marriage raises both man and creation out of sin and its defects. This explanation should exhibit both to believers, who seek to understand, and to unbelievers (primarily Jews and Muslims), from a common root, a solution "intelligible to all, and appealing because of its utility and the beauty of its reasoning" (1.1). Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo is the locus classicus for a theory of Incarnation and Atonement which exhibits Christ as providing the substitutive revenging satisfaction for the infinite dishonor God suffers at the sin of Adam (and company).1 There are elements in it, however, which seem to point quite differently from such a view. This meditation will attempt to bring further into the open how the rhetorical ergon of the work upon “faith and conscience”2 shows something new in this Paschal event, which cannot be well accommodated to the view which makes Christ a scapegoat killed for our sin.3 This ergon upon the conscience I take—in what I trust is a most suitably monastic fashion—to be more important than the theoretical theological shell which Anselm’s discussion with Boso more famously leaves behind. -

International Institute for Method in Theology, Newsletter 1

Newsletter 1 International Institute for Method in Theology September 2018 The International Institute for Method in Theology was launched at a colloquium held at Marquette University in March of 2017. The Institute is sponsored by the Marquette Lonergan Project, the Lonergan Research Institute of Regis College in the University of Toronto, and the Faculty of Theology at the Gregorian University, Rome. Representatives of all three institutions were present at the colloquium: Robert M. Doran, S.J., from Marquette, Eric Mabry, Interim Director of the Lonergan Research Institute, and Gerard Whelan, S.J., Professor of Theology at the Gregorian University. In the lecture that he presented at the colloquium, Robert Doran, Emmett Doerr Chair in Catholic Systematic Theology and Director of the Marquette Lonergan Project, narrated how the founding of the Institute is the long-term result of a suggestion that he had made to a Canadian Jesuit Provincial, Reverend William Addley, S.J., in 1984. Doran was living in Toronto at the time, teaching and writing at Regis College in the University of Toronto. The suggestion led to the establishment by Fr Addley of the Lonergan Research Institute. Recent research in the Frederick Crowe Archives at the LRI reveals how this new project of an Institute for Method in Theology was a part of the original vision of the LRI when it was founded. It was put on hold because the principal efforts of the LRI from its inception centered around the publication of Lonergan’s Collected Works with University of Toronto Press and the cataloguing and preservation of Lonergan’s archival papers. -

EPISTEMIC CIRCULARITY: MALIGNANT and BENIGN Michael Bergmann

EPISTEMIC CIRCULARITY: MALIGNANT AND BENIGN Michael Bergmann Consider the following dialogue: Juror #1: You know that witness named Hank? I have doubts about his trustworthiness. Juror #2: Well perhaps this will help you. Yesterday I overheard Hank claiming to be a trustworthy witness. Juror #1: So Hank claimed to be trustworthy did he? Well, that settles it then. I’m now convinced that Hank is trustworthy. Is the belief of Juror #1 that Hank is a trustworthy witness justified? Most of us would be inclined to say it isn’t. Juror #1 begins by having some doubts about Hank’s trustworthiness, and then he comes to believe that Hank is trustworthy. The problem is that he arrives at this belief on the basis of Hank’s own testimony. That isn’t reasonable. You can’t sensibly come to trust a doubted witness on the basis of that very witness’s testimony on his own behalf.1 Now consider the following soliloquy: Doubter: I have some doubts about the trustworthiness of my senses. After all, for all I know, they are deceiving me. Let’s see ... Hey, wait a minute. They are trustworthy! I recall many occasions in the past when I was inclined to hold certain perceptual beliefs. On each of those occasions, the beliefs I formed were true. I know that because the people I was with confirmed to me that they were true. By inductive reasoning, I can safely conclude from those past cases that my senses are trustworthy. There we go. It feels good to have those doubts about my senses behind me. -

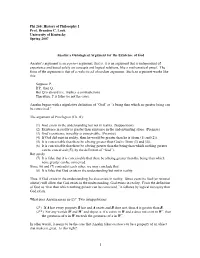

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof. Brandon C. Look University of Kentucky Spring 2007 Anselm’s Ontological Argument for the Existence of God Anselm’s argument is an a priori argument; that is, it is an argument that is independent of experience and based solely on concepts and logical relations, like a mathematical proof. The form of the argument is that of a reductio ad absurdum argument. Such an argument works like this: Suppose P. If P, then Q. But Q is absurd (i.e. implies a contradiction). Therefore, P is false (or not the case). Anselm begins with a stipulative definition of “God” as “a being than which no greater being can be conceived.” The argument of Proslogion (Ch. II): (1) God exists in the understanding but not in reality. (Supposition) (2) Existence in reality is greater than existence in the understanding alone. (Premise) (3) God’s existence in reality is conceivable. (Premise) (4) If God did exist in reality, then he would be greater than he is (from (1) and (2)). (5) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than God is (from (3) and (4)). (6) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which nothing greater can be conceived ((5), by the definition of “God”). But surely (7) It is false that it is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which none greater can be conceived. Since (6) and (7) contradict each other, we may conclude that (8) It is false that God exists in the understanding but not in reality. -

Bernard Lonergan on the Cross As Communication

Why the Passion? : Bernard Lonergan on the Cross as Communication Author: Mark T. Miller Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2235 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2008 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of Theology WHY THE PASSION?: BERNARD LONERGAN ON THE CROSS AS COMMUNICATION a dissertation by MARK T. MILLER submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosopy August 2008 © copyright by MARK THOMAS MILLER 2008 Abstract Why the Passion?: Bernard Lonergan, S.J. on the Cross as Communication by Mark T. Miller, directed by Frederick Lawrence This dissertation aims at understanding Bernard Lonergan’s understanding of how the passion of Jesus Christ is salvific. Because salvation is of human persons in a community, a history, and a cosmos, the first part of the dissertation examines Lonergan’s cosmology with an emphasis on his anthropology. For Lonergan the cosmos is a dynamic, interrelated hierarchy governed by the processes of what he calls “emergent probability.” Within the universe of emergent probability, humanity is given the ability to direct world processes with critical intelligence, freedom, love, and cooperation with each other and with the larger world order. This ability is not totally undirected. Rather, it has a natural orientation, a desire or eros for ultimate goodness, truth, beauty, and love, i.e. for God. When made effective through an authentic, recurrent cycle of experience, questioning, understanding, judgment, decision, action, and cooperation, this human desire for God results in progress. -

University at Buffalo Department of Philosophy Nousletter Interview with Jorge Gracia

University at Buffalo Department of Philosophy Nousletter Interview with Jorge Gracia Jorge Gracia is a polymath. He works in metaphysics/ontology, philosophical historiography, philosophy of language/hermeneutics, ethnicity/race/nationality issues, Hispanic/Latino issues, medieval/scholastic philosophy, Cuban and Argentinian art, and Borges. Gracia’s earliest work was in medieval philosophy. His more than three decades of contributions to medieval philosophy were recently recognized by his being named the winner of the most prestigious award in the field in 2011, the American Catholic Philosophical Association’s Aquinas Medal. That put him in the ranks of Jacques Maritain, Etienne Gilson, Bernard Lonergan, Joseph Owens, G. E. M. Anscombe, Peter Geach, Michael Dummett, John Finnis, Brian Davies, Anthony Kenny, Alisdair McIntyre and one Pope, Karol Wojtyla, and now one saint. Even after Gracia redirected some of his intellectual energies into other branches of philosophy, UB was still being ranked by the Philosophical Gourmet Report (PGR) as one of the best schools in medieval philosophy: 13th in 2006 and in the 15-20 range in 2008. If there were PGR rankings for Latin American philosophy or the philosophy of race and ethnicity, Jorge Gracia’s work would have enabled us to be highly ranked in those fields, higher, I suspect, than UB is in any other philosophical specialization. In the 2010 Blackwell Companion to Latin American Philosophy, Gracia was listed as one of the 40 most important figures in Latin American philosophy since the year 1500! Gracia is also one of the leaders in the emerging field of the philosophy of race and ethnicity. -

First Prize: an Analysis of the Ontological Argument of St Anselm by Ian Corfield

Philsoc Student Essay Prize, Michaelmas Term 2015 First Prize: An Analysis of the Ontological Argument of St Anselm by Ian Corfield Introduction St Anselm (1033CE-1109CE) was a philosopher and theologian and held the office of Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093CE until his death. He is remembered chiefly as the originator of the first ‘Ontological Argument’ for the existence of God. Ontological Arguments1 are a priori2 arguments purporting to establish the existence of God from the very definition of the same. Many such arguments have been advanced since Anselm’s, but Anselm’s original argument has remained a popular object of study. The Argument Anselm’s argument is set out in the second chapter of his work ‘The Proslogion’: And so, O Lord, … give me to understand … that thou art … a being than which none greater3 can be thought. Or can it be that there is no such being, since “the fool hath said in his heart, ‘There is no God’”? [Psalms 14.1; 53.1] But … this same fool … must be convinced that a being than which none greater can be thought exists at least in his understanding… . But clearly that than which a greater cannot be thought cannot exist in the understanding alone. For if it is actually in the understanding alone, it can be thought of as existing also in reality, and this is greater. Therefore, if that than which a greater cannot be thought is in the understanding alone, this same thing than which a greater cannot be thought is that than which a greater can be thought. -

New Directions for Catholic Theology. Bernard Lonergan's Move Beyond

JHMTh/ZNThG; 2019 26(1): 108–131 Benjamin Dahlke New Directions for Catholic Theology. Bernard Lonergan’s Move beyond Neo-Scholasticism DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/znth-2019-0005 Abstract: Wie andere aufgeschlossene Fachvertreter seiner Generation hat der kanadische Jesuit Bernard Lonergan (1904–1984) dazu beigetragen, die katho- lische Theologie umfassend zu erneuern. Angesichts der oenkundigen Gren- zen der Neuscholastik, die sich im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts als das Modell durchgesetzt hatte, suchte er schon früh nach einer Alternative. Bei aller Skep- sis gegenüber dem herrschenden Thomismus schätzte er Thomas von Aquin in hohem Maß. Das betraf insbesondere dessen Bemühen, die damals aktuellen wissenschaftlichen und methodischen Erkenntnisse einzubeziehen. Lonergan wollte dies ebenso tun. Es ging ihm darum, der katholischen Theologie eine neue Richtung zu geben, also von der Neuscholastik abzurücken. Denn diese berücksichtigte weder das erkennende Subjekt noch das zu erkennende Objekt hinreichend. Keywords: Bernard Lonergan, Jesuits, Neo-Scholasticism, Vatican II, Thomism Bernard Lonergan (1904–1984), Canadian-born Jesuit, helped to foster the re- newal of theology as it took place in the wake of Vatican II, as well in the council’s aftermath. He was aware of the profound changes the discipline was going through. Since the customary way of presenting the Christian faith – usu- ally identified with Neo-Scholasticism – could no longer be considered adequate, Lonergan had been working out an alternative approach. It was his intent to provide theology with new foundations that led him to incorporate contem- porary methods of science and scholarship into theological practice. Faith, as he thought, should be made intelligible to the times.1 Thus, Lonergan moved beyond the borders set up by Neo-Scholasticism. -

Lonergan Gatherings 7

James Gerard Duffy Words, don't come easy to me How can I find a way to make you see I Love You Words don't come easy1 Introduction Recently I saw the movie “Suite Française” (2014), a drama set in in the early years of the German occupation of France which portrays a developing romance between a French villager awaiting news of her husband and a dapper, refined German soldier who composes music. In the initial half dozen or so scenes they cannot speak to one another, for he is a German officer with a responsibility to follow orders, while she lives under the thumb of her controlling mother-in-law who forbids her to interact with the enemy. But they have already met in a shared love of music and in a few wordless encounters. How, then, are they going to meet, protect, and greet each other? In this essay my aim is threefold. In the first section I briefly comment on my experience of meeting, protecting, and greeting undergraduates and graduate students in the last twenty years in the United States and Mexico. In particular I focus on two questions: “What do you want?” and “What do we want?” In the second section I suggest some ways to implement heuristics in order to ask these two questions patiently and humbly. In the third and final section I respond to McShane’s claim in Lonergan Gatherings 6 regarding ‘the unashamed shamefulness’ of leading figures in Lonergan studies. 1 “Words Don’t Come Easy,” F.R. David. 1 I. -

Semi-Colonized: Malebranche, Freire and My Summer in Nanjing Shannon Dea, Dept

Shannon Dea Dept. of Philosophy Semi-Colonized: Malebranche, Freire and My Summer in Nanjing Shannon Dea, Dept. of Philosophy University of Waterloo [email protected] The opportunity Two dialogues Nicolas Malebranche, 1708 Paulo Freire, 1968 Malebranche’s dialogue • Chinese philosopher versus Christian philosopher • “insular eurocentrism” (Mungello, 1980) • Origins in mission work: an asymmetrical pedagogy Freire • “Banking model” of colonizer and colonized • Student-centred education • Conscientization • Dialogics What we did (two dialogues) • Critiqued Malebranche • Small groups in Chinese • “Li” translation • Oral dialogues A worry • What if dialogic pedagogy is more insidious than Malebranche’s? • What is the cost of effective teaching? Resistance is futile! When we make ourselves “accessible” to the students, we make it harder for them to resist us. Generalizing the worry… • Not just Chinese students • Not just Philosophy classes Why shouldn’t we colonize our students? • Because colonization creates intellectual monocultures • Because they are persons not objects. • Because, historically, colonialism has been the source of injustices. • Because we ought not to treat the future as a resource to be exploited. • Because this system of power is not worth reproducing just as it is. A question: How much should our students resist us? (And should we be the ones to decide?) Resistance vs. openness Semi-colonized? Even if our role as colonizers is inescapable, perhaps awareness of that fact, and resistance to it helps us to avoid the worst consequences of colonialism. Thank you! This talk would have been impossible without the intellectual generosity of Nicholas Ray and Rockney Jacobsen, who are jointly responsible for all of the good ideas and none of the bad ones.