After-Acquired Property and the Title Search

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Length of a Title Search in Tg Youdan

THE LENGTH OF A TITLE SEARCH IN NTARI T.G. YOUDAN* Toronto This article deals with the statutory provisions which in the Ontario registry system regulate the length of a vendor's chain of title and which in some cases extinguish claims against the land. The main focus of the article is analysis of newprovisions on the topic which were introduced in 1981 . However, in order to place these provisions in context the author outlines the history - of relevant conveyancing law andpractice in both England and Ontario, and he reviews the effect ofprevious legislation on the same topic. Il s'agit dans cet article des dispositions législatives qui réglementent, dans le système d'enregistrement de l'Ontario, la longueur de la chaîne des titres d'un vendeur et qui, dans certains cas, amène l'extinction du droit à un bien-fonds. L'auteurs'intéresse particulièrement à l'analyse des nouvelles dispositions apportées dans ce domaine en 1981 . Pour replacer ces dispositions dans leur contexte, 1986 CanLIIDocs 62 l'auteur fait, à grands traits, l'histoire du droit des transferts et de la pratique qui s'y rapporte en Angleterre et en Ontario etpasse brièvement en revue l'effet de la législation antérieure dans ce domaine. Introduction In 1981 a new Part III of the Ontario Registry Act was enacted. I It . deals with proof of title by a vendor of land and determines the appropriate length of a search; it also has corresponding provisions which extinguish claims against land on the ground of their. antiquity. This is a topic of great importance, and the new provisions were clently intended to make major changes in conveyancing law and practice. -

REVIEWING the TITLE SEARCH by Joseph E. Seagle, Esq. [email protected] INTRODUCTION Before One Can Discuss What a Title Agent Or

REVIEWING THE TITLE SEARCH By Joseph E. Seagle, Esq. [email protected] INTRODUCTION Before one can discuss what a title agent or examiner should or must review in the course of searching the chain of title, it is necessary to understand the basics and history of title examination. The Basics In Florida, it is common for title agents to receive either Title Search Reports or pro forma title insurance commitments from an examiner. The examiner may be an independent contractor, an employee of the title agency, or an employee of the title underwriter that will ultimately insure the title to be conveyed or mortgaged. In other instances, the title attorney or agent may conduct a personal search of the Public Records of the county where the real property to be insured is located. Examples of a title search report, pro forma commitment and raw title search are included in the appendix to this chapter. We will discuss all three methods of receiving the title information, and focus on the personal search method so that the agent may gain an understanding of the process the examiner will use to provide the end title information product. A History Lesson Prior to 1963, when the Florida legislature passed the Marketable Record Title Act (the “MRTA”), which will be discussed in more detail by Mr. Horak in another section of this manuscript, the examiner was required to search and abstract the insured property’s chain of title back to the beginning. This could require the examiner to search to find a land patent from the United States Government, a deed from the state of Florida, the Board of Trustees of the Internal Improvement Trust Fund, or a land grant from the King of Spain or the King of England. -

How to Buy Title Insurance In

How to Buy Title Insurance in [Insert State] This guide: • Covers the basics of title insurance. • Explains the need for title insurance. • Offers tips to shop for title insurance and closing services. • Gives you questions you should ask before you buy title insurance. [Name] [DOI Logo] [Superintendent of Insurance] [DOI Website Address] Drafting Note: This template has been developed for state departments of insurance who are interested in providing a consumer education publication regarding title insurance. The template was developed as a comprehensive guide that can be edited/personalized to meet the individual needs of a state. DRAFT: 3-23-215-25-21 1 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 Buying or Refinancing a Property Page 3 What is Title Insurance, and What Does it Cover? Page 4 Two Types of Title Insurance—Owner’s and Lender’s Policies Page 4 What Doesn’t Title Insurance Cover? Page 4 Who Sells Title Insurance? Page 5 The Right to Choose Your Own Title Agent/Company Page 5 Who Pays for Title Insurance? Page 5 What Does Title Insurance Cost? Page 6 Ask if You’re Eligible for Discounts Page 6 The Difference Between Title and Homeowners Insurance Page 6 Questions to Ask Before You Buy Title Insurance Page 6 The Real Estate Closing Page 7 Closing Agents Page 8 Questions to Ask When You Choose a Closing Agent Page 8 Closing Protection Page 8 Shop Around for Title Insurance and Closing Services Page 8 Cost Comparison Chart Page 9 Final Tips to Remember Page 10 How to File a Title Insurance Claim Page 10 The [INSERT DOI NAME] is Here to Help Page 10 Other Resources Available Page 11 Disclaimer: The information included in this publication is meant to serve as a guide and is not a substitute for legal or professional advice. -

TITLE STANDARDS October 10, 2019 10305 ICLE: State Bar Series

TITLE STANDARDS October 10, 2019 10305 ICLE: State Bar Series Thursday, October 10, 2019 TITLE STANDARDS 6 CLE Hours Including 1 Ethics Hour | 1 Professionalism Hour Copyright © 2019 by the Institute of Continuing Legal Education of the State Bar of Georgia. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of ICLE. The Institute of Continuing Legal Education’s publications are intended to provide current and accurate information on designated subject matter. They are off ered as an aid to practicing attorneys to help them maintain professional competence with the understanding that the publisher is not rendering legal, accounting, or other professional advice. Attorneys should not rely solely on ICLE publications. Attorneys should research original and current sources of authority and take any other measures that are necessary and appropriate to ensure that they are in compliance with the pertinent rules of professional conduct for their jurisdiction. ICLE gratefully acknowledges the eff orts of the faculty in the preparation of this publication and the presentation of information on their designated subjects at the seminar. The opinions expressed by the faculty in their papers and presentations are their own and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the Institute of Continuing Legal Education, its offi cers, or employees. The faculty is not engaged in rendering legal or other professional advice and this publication is not a substitute for the advice of an attorney. -

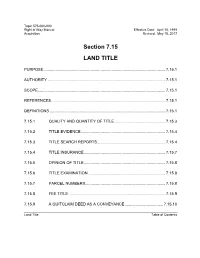

Right of Way Manual, Section 4.1, Land Title

Topic 575-000-000 Right of Way Manual Effective Date: April 15, 1999 Acquisition Revised: May 18, 2017 Section 7.15 LAND TITLE PURPOSE ............................................................................................................... 7.15.1 AUTHORITY ........................................................................................................... 7.15.1 SCOPE .................................................................................................................... 7.15.1 REFERENCES ........................................................................................................ 7.15.1 DEFINITIONS ......................................................................................................... 7.15.1 7.15.1 QUALITY AND QUANTITY OF TITLE .............................................. 7.15.3 7.15.2 TITLE EVIDENCE ............................................................................. 7.15.4 7.15.3 TITLE SEARCH REPORTS .............................................................. 7.15.4 7.15.4 TITLE INSURANCE .......................................................................... 7.15.7 7.15.5 OPINION OF TITLE .......................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.6 TITLE EXAMINATION ...................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.7 PARCEL NUMBERS......................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.8 FEE TITLE ....................................................................................... -

The Doctrine of After-Acquired Title

SMU Law Review Volume 11 Issue 2 Article 8 1957 The Doctrine of After-Acquired Title Charles Robert Dickenson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Charles Robert Dickenson, Comment, The Doctrine of After-Acquired Title, 11 SW L.J. 217 (1957) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol11/iss2/8 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE DOCTRINE OF AFTER-ACQUIRED TITLE INTRODUCTION This Comment will discuss briefly some of the problems which can arise when one person attempts by a valid instrument to convey more title than he actually has and subsequently acquires the title which he had purported to convey. Historically, in such a case the grantor is estopped to assert his after-acquired title against his grantee.' It has been said that this result is achieved through estoppel by deed rather than by estoppel in pais;' and that, therefore, there is no neces- sity for an adjudication of the rights of the parties in such a case;$ and that there is no necessity for showing a change in position of the party asserting the estoppel.4 Tiffany states that there is no necessity of regarding the after- acquired title as actually passing to the grantee.' However, there are numerous decisions and dicta in this country to the effect that the conveyance actually passes the grantor's after-acquired legal title to the grantee.! There have been,' and still are,' a number of statutory provisions to this effect in various states. -

The Scope of Title Examination in West Virginia: Can Reasonable Minds Differ

Volume 98 Issue 2 Article 4 January 1996 The Scope of Title Examination in West Virginia: Can Reasonable Minds Differ John W. Fisher II West Virginia University College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation John W. Fisher II, The Scope of Title Examination in West Virginia: Can Reasonable Minds Differ, 98 W. Va. L. Rev. (1996). Available at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr/vol98/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the WVU College of Law at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Law Review by an authorized editor of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fisher: The Scope of Title Examination in West Virginia: Can Reasonable M WEST VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW Volume 98 Winter 1996 Number 2 THE SCOPE OF TITLE EXAMINATION IN WEST VIRGINIA: CAN REASONABLE MINDS DIFFER? JOHN W. FISHER, II* I. INTRODUCTION ........................... 450 II. THE RECORDING ACTS ...................... 453 A. In the Beginning ....................... 453 B. Classifying the Early Recording Acts ............. 454 C. The West Virginia Statutes ................... 456 D. The West Virginia Recording Acts: The Aegis Afforded BFP'sfor Value ................. 459 E. The West Virginia Recording Acts: "Notice" is Not a Hindrance to "Creditors"................ 469 F. The West Virginia Recording Acts: While "Mort- gagees" are "Purchasers" Under the Statutes, Not All "Creditors" are "Creditors"............. 472 III. ESTABLISHING THE CHAIN OF TITLE ............. 474 IV. -

County Title Search Standards

COUNTY TITLE SEARCH STANDARDS (A) In general It is the responsibility of all persons making title searches (hereinafter referred to as “searchers”) to keep informed with respect to the time lag of indexing in all the various offices. Generally, in searching the indexes, the rule of idem sonans should be followed. Names such as “A. John Doe” should be searched both under “A” and “J” in indexes using first name divisions; names such as “C(K)arl” and C(K)atherine” should be searched under “C” and “K” in such indexes. Corporate names such as “John A. Smith, Inc.” should be searched both under “J” and “S.” If title is acquired by nickname, the proper name should also be searched. For example, “Tony” requires a search for “Anthony.” Attention is called to the fact that there are special headings used in the various indexes including “schools,” “churches,” “lot owners,” “vacations,” “annexations,” “trustees,” “lodges,” etc. Relative to corporate title holders, since the searcher is to include the Articles of Incorporation, he should also include all pertinent amendments, mergers or consolidations. If a change of name of a corporate title holder is disclosed in any records required by these standards to be searched, the search should be made under both the new name and the former name from the date of the name change. Land Contract vendees must be searched as fee owners. (B) New Indexes and Records It is the responsibility of all searchers to keep informed as to the creation of new indexes subsequent to the adoption of these Search Standards. -

THE AFTER-ACQUIRED PROPERTY CLAUSE Davm COHEN T and ALBERT B

April, 1939 University of Pennsylvania Law Review And American Law Register FOUNDED 1852 Copyright 1939, by the University of Pennsylvania VOLUME 87 APRIL, 1939 No. 6 THE AFTER-ACQUIRED PROPERTY CLAUSE DAVm COHEN t AND ALBERT B. GERBER $ At common law property to be created or acquired in the future could not be transferred or encumbered prior to the creation or ac- quisition of the property.1 Illustrative of the constant striving to make future assets available for present purposes was the attempt of com- mon-law lawyers to add to the conveyances of the day the words: "Quae quovismodo in futurum habere potero." 2 But, as Littleton says, these words were "void in law". The reasoning upon which the rule was based was simple--"A man cannot grant or charge that which he hath not." 3 This infallible bit of syllogistic logic received its first breakdown in the famous case of Grantham v. Hawley,4 the parent of the fictitious doctrine of "potential existence". Briefly stated, this prin- ciple permits the sale 5 or encumbrance of future personal property 6 t B. S. in Ed., x934, LL. B., 1937, Gowen Memorial Fellow, 1937-8, University of Pennsylvania; member of the Philadelphia bar; assistant counsel, Rural Electrification Administration. t B. S. in Ed., 1934, LL. B., 1937, Gowen Memorial Fellow, 1937-8, University of Pennsylvania; member of the Philadelphia bar; assistant counsel, Rural Electrification Administration. I. See 3 TIFFANY, REAL PROPERTY (2d ed. i92o) 2368. 2. The quotation in full reads: "Also, these words, which are commonly put in such releases, scil. -

Title Examinations and Title Issues

CHAPTER 7 Title Examinations and Title Issues R. Prescott Jaunich, Esq. Downs Rachlin Martin PLLC, Burlington Timothy S. Sampson, Esq. Downs Rachlin Martin PLLC, Burlington § 7.1 Introduction ................................................................................. 7–1 § 7.2 Marketable Title .......................................................................... 7–4 § 7.2.1 Vermont Title Standards ............................................... 7–4 § 7.2.2 Common Law Marketable Title—Permits as Encumbrances ............................................................... 7–6 § 7.2.3 Vermont Marketable Record Title Act ........................ 7–10 (a) Person ................................................................ 7–11 (b) Unbroken Chain of Title .................................... 7–11 (c) Conveyance ....................................................... 7–12 (d) Preserved Claims Under the Act ........................ 7–13 § 7.3 Conveyancing Requirements .................................................... 7–15 § 7.3.1 Vermont Deed Customs .............................................. 7–15 § 7.3.2 Deeds by Trustees and Deeds to Trust ........................ 7–17 § 7.3.3 Deeds by Executors, Administrators and Guardians .. 7–17 § 7.3.4 Deeds by Divorce Judgment ....................................... 7–18 § 7.3.5 Probate Decree ............................................................ 7–18 § 7.4 Identifying the Real Estate and Property Descriptions .......... 7–18 § 7.4.1 Reference to Prior Deeds and Instruments -

The Title Opinion: an Overview

The Title Opinion: An Overview A title opinion may only be drafted by a licensed attorney. This overview is provided only for educational use and does not constitute and may not be used to give legal advice. The first step in a title opinion is a title search. A title search entails the detailed review of real property records in the county where the land is located. Each state maintains a recording system, which is like a library made up of title-related documents. In West Virginia, real property records are stored in the county clerk’s office. These records include copies of deeds, mortgages, and other instruments that convey an interest in real property to a new owner. The county also maintains estate records, which become relevant when land is given to a new owner through a will. One step in a title search is researching the chain of title: an attorney develops a full chronology of how the property has transferred between owners. For example, A deeds to B; B deeds to C; D inherits property from C; D deeds to E; E mortgages to X; E deeds to F subject to X’s mortgage; X executes a satisfaction of the mortgage; F deeds to G; and so forth.1 The history of the property is frequently much more complicated because, for example, properties may be divided into multiple parcels or conveyed to multiple owners. After the chain of title has been established, the title attorney will identify other encumbrances and activities appearing in the records that have the potential to cloud title. -

Title Insurance Protects Your Investment

Title Insurance Protects Your Investment During the closing process, make sure you request an Owner’s Policy of Title Insurance in addition to a Loan Policy By New Mexico Land Title Association After a months-long search, you finally find your family’s dream home—a safe neighborhood and great schools, and a big backyard for the swimming pool you plan to build. You move in and hire a contractor, but a few days into construction the contractor finds an underground utility line running right through the middle of your backyard. You check your title insurance policy, and find out that the title search did not discover the easement. What do you do? Here’s another scenario. After retiring, you decide to downsize and buy a smaller townhome on a golf course. A month after you move in, a man knocks on your door and claims he is the real owner of your home. Upon further investigation, you discover that the sellers weren’t the real owners, but people posing as the owners. They searched the public records for a home with out-of-state owners, forged and recorded a fictitious deed, then sold the property to you before the real owners (or you) discovered the scam. Sound farfetched? Both of these scenarios really happened. To protect your investment from these and other serious problems, make sure you have title insurance. Title Insurance 101 Title insurance insures that the title to your property is clear, with no known liens or encumbrances, such as unpaid property taxes, recorded liens, or street and sewer easements.