THE AFTER-ACQUIRED PROPERTY CLAUSE Davm COHEN T and ALBERT B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Right of Way Manual, Section 4.1, Land Title

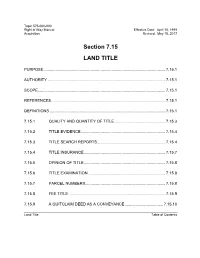

Topic 575-000-000 Right of Way Manual Effective Date: April 15, 1999 Acquisition Revised: May 18, 2017 Section 7.15 LAND TITLE PURPOSE ............................................................................................................... 7.15.1 AUTHORITY ........................................................................................................... 7.15.1 SCOPE .................................................................................................................... 7.15.1 REFERENCES ........................................................................................................ 7.15.1 DEFINITIONS ......................................................................................................... 7.15.1 7.15.1 QUALITY AND QUANTITY OF TITLE .............................................. 7.15.3 7.15.2 TITLE EVIDENCE ............................................................................. 7.15.4 7.15.3 TITLE SEARCH REPORTS .............................................................. 7.15.4 7.15.4 TITLE INSURANCE .......................................................................... 7.15.7 7.15.5 OPINION OF TITLE .......................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.6 TITLE EXAMINATION ...................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.7 PARCEL NUMBERS......................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.8 FEE TITLE ....................................................................................... -

The Doctrine of After-Acquired Title

SMU Law Review Volume 11 Issue 2 Article 8 1957 The Doctrine of After-Acquired Title Charles Robert Dickenson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Charles Robert Dickenson, Comment, The Doctrine of After-Acquired Title, 11 SW L.J. 217 (1957) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol11/iss2/8 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE DOCTRINE OF AFTER-ACQUIRED TITLE INTRODUCTION This Comment will discuss briefly some of the problems which can arise when one person attempts by a valid instrument to convey more title than he actually has and subsequently acquires the title which he had purported to convey. Historically, in such a case the grantor is estopped to assert his after-acquired title against his grantee.' It has been said that this result is achieved through estoppel by deed rather than by estoppel in pais;' and that, therefore, there is no neces- sity for an adjudication of the rights of the parties in such a case;$ and that there is no necessity for showing a change in position of the party asserting the estoppel.4 Tiffany states that there is no necessity of regarding the after- acquired title as actually passing to the grantee.' However, there are numerous decisions and dicta in this country to the effect that the conveyance actually passes the grantor's after-acquired legal title to the grantee.! There have been,' and still are,' a number of statutory provisions to this effect in various states. -

The Scope of Title Examination in West Virginia: Can Reasonable Minds Differ

Volume 98 Issue 2 Article 4 January 1996 The Scope of Title Examination in West Virginia: Can Reasonable Minds Differ John W. Fisher II West Virginia University College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation John W. Fisher II, The Scope of Title Examination in West Virginia: Can Reasonable Minds Differ, 98 W. Va. L. Rev. (1996). Available at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr/vol98/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the WVU College of Law at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Law Review by an authorized editor of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fisher: The Scope of Title Examination in West Virginia: Can Reasonable M WEST VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW Volume 98 Winter 1996 Number 2 THE SCOPE OF TITLE EXAMINATION IN WEST VIRGINIA: CAN REASONABLE MINDS DIFFER? JOHN W. FISHER, II* I. INTRODUCTION ........................... 450 II. THE RECORDING ACTS ...................... 453 A. In the Beginning ....................... 453 B. Classifying the Early Recording Acts ............. 454 C. The West Virginia Statutes ................... 456 D. The West Virginia Recording Acts: The Aegis Afforded BFP'sfor Value ................. 459 E. The West Virginia Recording Acts: "Notice" is Not a Hindrance to "Creditors"................ 469 F. The West Virginia Recording Acts: While "Mort- gagees" are "Purchasers" Under the Statutes, Not All "Creditors" are "Creditors"............. 472 III. ESTABLISHING THE CHAIN OF TITLE ............. 474 IV. -

Title Examinations and Title Issues

CHAPTER 7 Title Examinations and Title Issues R. Prescott Jaunich, Esq. Downs Rachlin Martin PLLC, Burlington Timothy S. Sampson, Esq. Downs Rachlin Martin PLLC, Burlington § 7.1 Introduction ................................................................................. 7–1 § 7.2 Marketable Title .......................................................................... 7–4 § 7.2.1 Vermont Title Standards ............................................... 7–4 § 7.2.2 Common Law Marketable Title—Permits as Encumbrances ............................................................... 7–6 § 7.2.3 Vermont Marketable Record Title Act ........................ 7–10 (a) Person ................................................................ 7–11 (b) Unbroken Chain of Title .................................... 7–11 (c) Conveyance ....................................................... 7–12 (d) Preserved Claims Under the Act ........................ 7–13 § 7.3 Conveyancing Requirements .................................................... 7–15 § 7.3.1 Vermont Deed Customs .............................................. 7–15 § 7.3.2 Deeds by Trustees and Deeds to Trust ........................ 7–17 § 7.3.3 Deeds by Executors, Administrators and Guardians .. 7–17 § 7.3.4 Deeds by Divorce Judgment ....................................... 7–18 § 7.3.5 Probate Decree ............................................................ 7–18 § 7.4 Identifying the Real Estate and Property Descriptions .......... 7–18 § 7.4.1 Reference to Prior Deeds and Instruments -

Off-Record Risks for Bona Fide Purchasers of Interests in Real Property

Volume 72 Issue 1 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 72, 1967-1968 10-1-1967 Off-Record Risks for Bona Fide Purchasers of Interests in Real Property Ralph T. Straw Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Ralph T. Straw Jr., Off-Record Risks for Bona Fide Purchasers of Interests in Real Property, 72 DICK. L. REV. 35 (1967). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol72/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OFF-RECORD RISKS FOR BONA FIDE PURCHASERS OF INTERESTS IN REAL PROPERTY By RALPH L. STRAW, JR.* Introduction I. Forgeriesand Frauds A. Forged Instruments B. FraudulentReleases C. Defrauding of a Grantor II. Incapacity of a Grantor A. Mental Incapacity of a Grantor B. Infant Grantor C. Legal Incapacity II. Lack of an Essential Formality in the Execution of an Instrument A. Lack of Delivery B. Lack of Acknowledgment IV. Mechanics' Liens V. UnrecordedFamily Rights A. Dower B. Rights of Pretermittedor After-Born Children C. Community Property Rights VI. PriorAdverse Possessionand Undisclosed Easements A. PriorAdverse Possession B. Undisclosed PrescriptiveEasements C. Undisclosed Implied Easements VII. Failure to Inquire with respect to Possession Not on its Face Inconsistent with Purchaser'sRights VIII. Tolled Limitations Periods IX. Prior Holder in Chain of Title Senior in Record but Junior in Time of Actual Notice X. -

Estoppel by Deed--Conveyance of Interest Subsequently Acquired As Heir--Warranty in Quitclaim Deed As Basis for Estoppel

Volume 44 Issue 1 Article 12 December 1937 Estoppel by Deed--Conveyance of Interest Subsequently Acquired as Heir--Warranty in Quitclaim Deed as Basis for Estoppel J. H. H. West Virginia University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation J. H. H., Estoppel by Deed--Conveyance of Interest Subsequently Acquired as Heir--Warranty in Quitclaim Deed as Basis for Estoppel, 44 W. Va. L. Rev. (1937). Available at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr/vol44/iss1/12 This Recent Case Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the WVU College of Law at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Law Review by an authorized editor of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. H.: Estoppel by Deed--Conveyance of Interest Subsequently Acquired as WEST VIRGINIA LAW QUARTERLY element would be particularly important in view of the well estab- 1 lished rule that rents belong to the owner of property on rent day." Therefore it is submitted that our court reached a result not only in accord with the weight of authority, but, what is more important, also in accord with the policy of maintaining practical and well settled rules concerning wills and their construction. J. G. McC. ESTOPPEL BY DEED - CONVEYANCE OF INTEREST SUBSEQUENTLY ACQUIRED AS HER - WARRANTY IN QUITCLAim DEED As BAsIS FOR ESTOPPEL. -- T devised to W, his wife, a life estate in his property, with power of consumption of the corpus for her support, re- mainder to his children in fee, share and share alike. -

The Growing Uncertainty of Real Estate Titles

North Dakota Law Review Volume 65 Number 1 Article 1 1989 The Growing Uncertainty of Real Estate Titles Owen L. Anderson Charles T. Edin Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/ndlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Owen L. and Edin, Charles T. (1989) "The Growing Uncertainty of Real Estate Titles," North Dakota Law Review: Vol. 65 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://commons.und.edu/ndlr/vol65/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Dakota Law Review by an authorized editor of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GROWING UNCERTAINTY OF REAL ESTATE TITLES* OWEN L. ANDERSON** AND CHARLES T. EDIN*** INTRODUCTION ............................................ 2 I. MALLOY V BOETTCHER ............................. 3 A. THE FOUR OPINIONS ............................... 6 B. THE VARIOUS RULES COMPARED ................... 15 1. The North Dakota Statutory (Field Code) Rule. 15 2. The Common-law Rationale .................... 18 3. The Rationalefor Rejecting the Common-law R u le ............................................. 19 4. What Should the North Dakota Rule Be? ...... 24 C. THE "EXCEPTION" "RESERVATION" PROBLEM ..... 26 D. DOROTHY'S LIFE ESTATE IN THE ENTIRE RESERVED INTEREST ............................... 34 II. WEHNER V SCHROEDER ............................. 44 A. SUMMARY OF WEHNER I AND WEHNER 11 .......... 48 B. WEHNER I - ANALYSIS ............................. 51 1. Statutes of Limitation ........................... 51 2. Protection of Bona Fide Purchaser.............. 54 a. "Merger of Title" ............................ 55 b. "Merger of Title" and "Estoppel by Deed". 56 C. WEHNER H - ANALYSIS ............................ 62 1. -

DEALING with UNWRITTEN TITLE TRANSFERS Troy R

DEALING WITH UNWRITTEN TITLE TRANSFERS Troy R. Covington, Bloom Parham, LLP Dealing with potential unwritten title transfers requires that property owners and their counsel have a firm grasp on the facts regarding an owner’s use of the property and regarding the actions of adjoining landowners and others who potentially could make a claim of ownership on the property. Whether a court will reach a determination that ownership of property has been transferred or not depends on the precise nature of the usage of the property by the owner and those with potentially competing interests. As such, it is incumbent upon property owners and lawyers to know as exactly as possible what is happening with property and when. If a property owner does not have the details of his ownership at his fingertips, he is more likely to fall victim to the claims of one who might have an interest in filling in those gaps in a manner adverse to the owner’s interest. This paper provides a broad overview of the Georgia statutes and case law dealing with encroachments, acquiescence, estoppel, and adverse possession. The paper seeks to set forth the basic parameters of these legal doctrines to assist practitioners in recognizing property ownership issues and to make them aware both of potential remedies for these issues and of potential problems that may arise in the absence of any action. I. Encroachments A. Actions for Ejectment and Trespass “Georgia law allows an owner of real property to bring an ejectment action to remove an adjoining owner who, either by inadvertence or with predatory intent, encroaches upon the property of his neighbor.” MVP Inv. -

(A) Forte Prelims

GOOD FAITH IN CONTRACT AND PROPERTY GOOD FAITH IN CONTRACT AND PROPERTY Edited by A. D. M. Forte OXFORD – PORTLAND OREGON 1999 Hart Publishing Oxford and Portland, Oregon Published in North America (US and Canada) by Hart Publishing c/o International Specialized Book Services 5804 NE Hassalo Street Portland, Oregon 97213-3644 USA Distributed in the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg by Intersentia, Churchillaan 108 B2900 Schoten Antwerpen Belgium Distributed in Australia and New Zealand by Federation Press John St Leichhardt NSW 2000 © The contributors severally 1999 The contributors have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, to be identified as the authors of this work Hart Publishing Ltd is a specialist legal publisher based in Oxford, England. To order further copies of this book or to request a list of other publications please write to: Hart Publishing Ltd, Salter’s Boatyard, Oxford OX1 4LB Telephone: +44 (0)1865 245533 or Fax: +44 (0)1865 794882 e-mail: [email protected] British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data Available ISBN 1 84113–047–8 Typeset by Hope Services (Abingdon) Ltd. Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Biddles Ltd, Guildford and Kings Lynn. CONTENTS Table of Cases xi Table of Legislation and Delegated Legislation xix Table of International Conventions and Principles xxiii Preface The Right Honourable the Lord Rodger of Earlsferry, Lord President xiv 1. Introduction 1 A.D.M. Forte 2. Good Faith in the Scots Law of Contract: An Undisclosed Principle? 5 Hector L. MacQueen 3. Good Faith: A Matter of Principle? 39 Ewan McKendrick 4. -

Implications for Patent Licensing

V3I2SERVER.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) Licensee Patent Validity Challenges Following MedImmune: Implications for Patent Licensing by ALFRED C. SERVER∗ AND PETER SINGLETON**♦ I. INTRODUCTION .........................................................................245 II. MEDIMMUNE V. GENENTECH AND THE NONREPUDIATING LICENSEE IN GOOD STANDING.....248 A. Holding Of The U.S. Supreme Court In MedImmune.....249 B. Issues Not Decided In MedImmune...................................254 C. The Licensor’s Dilemma.....................................................258 III. LICENSEE ESTOPPEL AND THE SCOPE OF LEAR’S REPUDIATION OF THE DOCTRINE .......................................260 A. The Doctrine Of Licensee Estoppel ..................................261 1. Early U.S. Case Law..................................................262 2. The U.S. Supreme Court’s Affirmation of Licensee Estoppel ......................................................265 3. Limits to the Doctrine of Licensee Estoppel..........268 a) The Eviction Limitation ..................................268 b) Expiration, Termination, and the Repudiation Limitation ..................................272 4. Two recognized versions of the doctrine of licensee estoppel........................................................283 5. Exceptions to the estoppel doctrine........................288 a) Patent policy exceptions .................................289 b) Antitrust-related exceptions ..........................291 B. Automatic Radio Manufacturing v. Hazeltine Research ......295 2010 Alfred -

Roman Law and Common Law : Comparative Outline

ROMAN LAW & COMMON LAW ROMAN LAW AND COMMON LAW A COMPARISON IN OUTLINE BY THE LATE W.W. BUCKLAND AND ARNOLD D. McNAIR C.B.E., LL.D., Q.C., F.B.A. Fellow of Gon<ville and Cams College, Cambridge SECOND EDITION REVISED BY F. H. LAWSON D.C.L., F.B.A. Professor of Comparative Law in the University of Oxford and Fellow of Brasenose College CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao Paulo, Delhi Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www. Cambridge. org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521043618 © Cambridge University Press 1936, 1952, 1965 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1936 Second edition 1952 Reprinted with corrections 1965 Reprinted 1974 This digitally printed version 2008 A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library ISBN 978-0-521-04361-8 hardback ISBN 978-0-521-08608-0 paperback CONTENTS Preface page ix Preface to the Second Edition xi Note on the ig6$ Impression xiii Introduction XV Abbreviations xxiii Chapter I. THE SOURCES 1 I . Legislation 1 2. Case Law 6 3. Juristic Writings 10 4. Custom 15 5. General Reflexions 18 Excursus: Roman and English Methods 21 Chapter II. THE LAW OF PERSONS 23 1. Territorial and Personal Law 23 2. -

Scienze Giuridiche L'acquiescenza Nel Diritto

Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN SCIENZE GIURIDICHE CiClo XXXII Settore Concorsuale: 12/E1 Settore Scientifico Disciplinare: IUS/13 L’ACQUIESCENZA NEL DIRITTO INTERNAZIONALE Presentata da: Dott. Niccolò Lanzoni Coordinatore Dottorato: Supervisore: Chiar.mo Prof. Chiar.mo Prof. Andrea Morrone Attila M. Tanzi Esame finale anno 2020 1 2 Ringraziamenti Non è sempliCe trovare le parole giuste per ringraziare Così tante persone in Così poco spazio. Il primo e più sentito dei ringraziamenti va al Professor Attila Tanzi, mio supervisore e Maestro, Con il quale, nel Corso di questi lunghi, spossanti, entusiasmanti e irripetibili anni ho avuto modo di stringere un magnifiCo rapporto professionale e, prima ancora, personale. Inutile dire Che senza di lui questa tesi non avrebbe mai visto la luce. Il seCondo ringraziamento va, senza dubbio, a Gian Maria Farnelli. Solo Chi ha avuto il piaCere di lavorarci insieme può apprezzarne appieno la Competenza e le qualità umane. Grazie davvero per il Costante e generoso aiuto. Ringrazio la Professoressa Elisa BaronCini per avermi gentilmente Coinvol- to nei suoi stimolanti progetti, nonché i miei fantastiCi Colleghi LudoviCa Chiussi e FrancesCo Cunsolo per i bei momenti passati in Compagnia. Ringrazio inoltre i due revisori, il Professor Giulio Bartolini e il Professor Cesare Pitea, per gli utili Commenti alla preCedente versione del testo. Un ringraziamen- to speCiale va alla Profesora Andrea Lucas Garín per avermi invitato e splendidamente aCColto al- l’Heidelberg Center para AmériCa Latina a Santiago del Cile: è stata un’esperienza indimentiCabile. Un ulteriore e profondo ringraziamento va alla mia famiglia, Che mi supporta (e sopporta) da sem- pre.