Etruscan Women and Social Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cneve Tarchunies Rumach

Classica, Sao Paulo, 718: 101-1 10, 199411995 Cneve Tarchunies Rumach R.ROSS HOLLOWAY Center for Old World Archaeology and Art Brown University RESUMO: O objetivo do Autor neste artigo e realizar um leitura historica das pinturas da Tumba Francois em Vulci, detendo-se naquilo que elas podem elucidar a respeito da sequencia dos reis romanos do seculo VI a.C. PALAVRAS CHAVE: Tumba Francois; realeza romana; uintura mural. The earliest record in Roman history, if by history we mean the union of names with events, is preserved in the paintings of an Etruscan tomb: the Francois Tomb at Vulci. The discovery of the Francois Tomb took place in 1857. The paintings were subsequently removed from the walls and became part of the Torlonia Collection in Villa Albani where they remain to this day. The decoration of the tomb, like much Etruscan funeral art, draws on Greek heroic mythology. It also included a portrait of the owner, Vel Saties, and beside him the figure of a woman named Tanaquil, presumably his wife (this figure has become almost completely illegible). In view of the group of historical personages among the tomb paintings, this name has decided resonance with better known Tanaquil, in Roman tradition the wife of Tarquinius Priscus. The historical scene of the tomb consists of five pairs of figures drawn from Etruscan and Roman history. These begin with the scene (A) Mastarna (Macstma) freeing Caeles Vibenna (Caile Vipinas) from his bonds (fig.l). There follow four scenes in three of which an armed figure dispatches an unarmed man with his sword. -

L31 Passage Romulus and Titus Tatius (Uncounted King of Rome

L31 Passage Romulus and Titus Tatius (uncounted king of Rome) are gone Numa Pompilius is made the second king Numa known for peace, religion, and law Temple of Janusdoors open during war, closed during peace; during Numa’s reign, doors were closed L32 Passage Tullus Hostilius becomes third king (mega war) Horatii triplets (Roman) vs. Curiatii (Albans) Two of Horatii are killed immediately; Curiatii are all wounded Final remaining Horatius separates Curiatii and kills them by onebyone Horatius’ sister engaged to one of the Curiatii; weeps when she sees his stuff; Horatius, angry that she doesn’t mourn her own brothers, kills her L33 Passage Tullus Hostilius makes a mistake in a religious sacrifice to Jupiter Jupiter gets angry and strikes his house with a lightning bolt, killing Tullus Ancus Marcius becomes fourth king Ancus Marcius is Numa’s grandson Lucumo (later Lucius Tarquinius Priscus) moves from Etruria to Rome to hold public office at the advice/instigation of Tanaquil While moving, eagle takes his cap and puts it back on Lucumo’s head Tanaquil interprets it as a sign of his future greatness throws Iggy Iggs parties, wins favor becomes guardian of the king’s children upon Ancus’ death L34 Passage Lucius Tarquinius Priscus makes himself fifth king Servius Tullius is a slave in the royal household Tanaquil has a dream that Servius’ head catches on fire She interprets as a sign of greatness LTP makes Servius his adopted son hire deadly shepherd ninjas to go into the palace and assassinate -

Greenfield, P. N. 2011. Virgin Territory

_____________________________________ VIRGIN TERRITORY THE VESTALS AND THE TRANSITION FROM REPUBLIC TO PRINCIPATE _____________________________________ PETA NICOLE GREENFIELD 2011 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics and Ancient History The University of Sydney ABSTRACT _____________________________________ The cult of Vesta was vital to the city of Rome. The goddess was associated with the City’s very foundation, and Romans believed that the continuity of the state depended on the sexual and moral purity of her priestesses. In this dissertation, Virgin Territory: The Vestals and the Transition from Republic to Principate, I examine the Vestal cult between c. 150 BCE and 14 CE, that is, from the beginning of Roman domination in the Mediterranean to the establishment of authoritarian rule at Rome. Six aspects of the cult are discussed: the Vestals’ relationship with water in ritual and literature; a re-evaluation of Vestal incestum (unchastity) which seeks a nuanced approach to the evidence and examines the record of incestum cases; the Vestals’ extra-ritual activities; the Vestals’ role as custodians of politically sensitive documents; the Vestals’ legal standing relative to other Roman women, especially in the context of Augustus’ moral reform legislation; and the cult’s changing relationship with the topography of Rome in light of the construction of a new shrine to Vesta on the Palatine after Augustus became pontifex maximus in 12 BCE. It will be shown that the cult of Vesta did not survive the turmoil of the Late Republic unchanged, nor did it maintain its ancient prerogative in the face of Augustus’ ascendancy. -

Course Summary

PRELIMINARY COURSE SYLLABUS Quarter: Spring 2021 Course Title: The Roman World Course Code: HIS 197 W Instructor: Gary Devore Course Summary: This course will look at the lives of famous Romans (such as Julius Caesar, Nero, Hadrian, and Constantine) as well as the more obscure but still interesting Romans (like fraternal revolutionaries Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, the dictator Sulla, the 3rd-century emperor Gallienus, and the powerful women who safeguarded the patrician Cornelius family). Through these personages, we will see how Rome grew from a tiny village of mud huts clustered atop hills along the Tiber River into an empire controlling land and people across all of Europe, from Spain to the Near East and from Britain to the shores of the Sahara. Grade Options and Requirements: Each week the students should 1) watch the video treatment of the material, 2) read the assigned reading, 3) take an online “open book” quiz based on the reading to check comprehension and if possible 4) take part in an online Discussion Topic sessions (an hour on Zoom, Fridays from 7-8pm Pacific time). (The Zoom discussions are optional and will be recorded so those not able to attend can watch them later.) Every week will start with an announcement reminding the students of what ancient Roman we are meeting that week and telling the students what they should be on the look out for (in the readings and the video material) with regards to the Discussion Topic sessions. A brief final essay exam is available for those wishing to take the course for a grade. -

Chapter 3 Early Rome

Chapter 3 Early Rome 1. THE WARLIKE MEDITERRANEAN Romans lived in a dangerous neighborhood. The whole of Italy was an anarchic world of contending tribes, independent cities, leagues of cities, and federations of pre-state tribes. The Mediterranean world beyond Italy was not much differ- ent. During the period of Rome’s emergence (ca. 500–300 b.c.) the Persian Empire consolidated its hold on the Middle East and the eastern Mediterranean, including parts of the Greek inhabited world, and for two centuries independent Greek city- states and Persians confronted each other, sometimes belligerently, and sometimes as allies. Simultaneously, individual Greek city states waged wars with each other as did alliances of Greek states among themselves. Wars lasted for generations. The great Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta and their allies raged in two phases from 460 to 446 b.c. and from 431 to 404 b.c. Sixty-five years later, Mace- donians subdued the squabbling city states of Greece, bringing a kind of order to that war-torn land. Four years after defeating the Greeks, the Macedonians under Alexander the Great went on to conquer the Persian Empire. Their power reached from the Aegean to Afghanistan and India, but not for long as a unified state. After Alexander’s death his successors quarreled and fought each other to a standstill. While these wars were going on in the eastern Mediterranean the Phoenician colony of Carthage emerged as a belligerent, imperialistic power in the western Mediterranean. Just a three- or four-day sail from Rome, Carthage was potentially a much more dangerous than any power in Italy. -

Famous Men of Rome

FAMOUS MEN OF ROME FAMOUS MEN OF ROME BY JOHN A. HAAREN YESTERDAY’S CLASSICS CHAPEL HILL, NORTH CAROLINA Cover and arrangement © 2006 Yesterday’s Classics. This edition, first published in 2006 by Yesterday’s Classics, is an unabridged repub- lication of the work originally published by University Publishing Co. in 1904. For a listing of books published by Yesterday’s Classics, please visit www.yesterdaysclassics.com. Yesterday’s Classics is the publishing arm of the Baldwin Project which presents the complete text of dozens of classic books for children at www.mainlesson.com under the editorship of Lisa M. Ripperton and T. A. Roth. ISBN-10: 1-59915-046-8 ISBN-13: 978-1-59915-046-8 Yesterday’s Classics PO Box 3418 Chapel Hill, NC 27515 PREFACE The study of history, like the study of a landscape, should begin with the most conspicuous features. Not until these have been fixed in memory will the lesser features fall into their appropriate places and assume their right proportions. In order to attract and hold the child’s attention, each conspicuous feature of history presented to him should have an individual for its center. The child identifies himself with the personage presented. It is not Romulus or Hercules or Cæsar or Alexander that the child has in mind when he reads, but himself, acting under the prescribed conditions. Prominent educators, appreciating these truths, have long recognized the value of biography as a preparation for the study of history and have given it an important place in their scheme of studies. The former practice in many elementary schools of beginning the detailed study of American history without any previous knowledge of general history limited the pupil’s range of vision, restricted his sympathies, and left him without material for comparisons. -

OCR Classical Civilization GCSE

de Romanis has been designed as a spring-board to facilitate future study in the full range of Classical subjects available at GCSE. Culture and context material within de Romanis relates to a significant proportion of the material covered by the OCR specifications for GCSEs in Classical Civilisation and Ancient History. Details of this overlap are listed below. Each chapter of de Romanis includes original sources for study and analysis; this develops the skills students will need at GCSE. inevitably, students who continue to a GCSE in one of these subjects will need to cover the relevant material within greater depth during their GCSE courses. OCR Classical Civilization GCSE Thematic study: Myth and Religion OCR Classical Civilization GCSE specification content Relevant material included within de Romanis ● Gods ● Jupiter, Neptune, Vulcan, Mercury, Mars, Pluto, Apollo, Juno, Venus, Minerva, Diana, Bacchus, Vesta and Ceres ● The Universal Hero / Hercules ● the myth of Hercules and Cacus; Hercules’ role as protector of Rome ● Religion and the City ● the Pantheon ● Roman priests such as the Pontifex Maximus; augurs, the Vestal Virgins ● animal sacrifice; role of the Haruspex ● Myth and the City: Foundation Stories ● Aeneas’ leadership of the Trojans, his arrival and settlement in Italy ● the founding of Alba Longa and the line of kings ● the founding of Rome (Romulus and Remus) ● Festivals ● the Lupercalia and Saturnalia ● Myth and Symbols of Power ● the Prima Porta of Augustus ● the Ara Pacis ● Death and Burial ● Parentalia and Lemuria ● Journeying to the Underworld ● poetic descriptions of the Underworld and its monsters Thematic study: Women in the Ancient World ● Women of Legend ● rape of the Sabine women ● Lucretia and Tarquinius Superbus ● Women and religion ● Vestal Virgins ● the Sibyl ● Women and power ● case-studies of other powerful women, e.g. -

Pudicitia: the Construction and Application of Female Morality in the Roman Republic and Early Empire

Pudicitia: The Construction and Application of Female Morality in the Roman Republic and Early Empire Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Graduate Program in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies Professor Cheryl Walker, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies by Kathryn Joseph May 2018 Copyright by Kathryn Elizabeth Spillman Joseph © 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisors for their patience and advice as well as my cohort in the Graduate Program in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies. Y’all know what you did. iii ABSTRACT Pudicitia: The Construction and Application of Female Morality in the Roman Republic and Early Empire A thesis presented to the Graduate Program in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Kathryn Joseph In the Roman Republic and early Empire, pudicitia, a woman’s sexual modesty, was an important part of the traditional concept of female morality. This thesis strives to explain how traditional Roman morals, derived from the foundational myths in Livy’s History of Rome, were applied to women and how women functioned within these moral constructs. The traditional constructs could be manipulated under the right circumstances and for the right reasons, allowing women to act outside of traditional gender roles. By examining literary examples of women who were able to step outside of traditional gender roles, it becomes possible to understand the difference between projected male ideas on ideal female morality, primarily pudicitia, and actuality. -

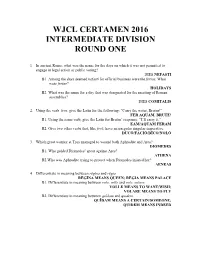

Wjcl Certamen 2016 Intermediate Division Round One

WJCL CERTAMEN 2016 INTERMEDIATE DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. In ancient Rome, what was the name for the days on which it was not permitted to engage in legal action or public voting? DIES NEFASTI B1. Among the days deemed nefasti for official business were the feriae. What were feriae? HOLIDAYS B2. What was the name for a day that was designated for the meeting of Roman assemblies? DIES COMITALIS 2. Using the verb fero, give the Latin for the following: “Carry the water, Brutus!” FER AQUAM, BRUTE! B1. Using the same verb, give the Latin for Brutus’ response: “I’ll carry it.” EAM/AQUAM FERAM B2. Give two other verbs that, like ferō, have an irregular singular imperative. DUCŌ/FACIŌ/DĪCO/NOLŌ 3. Which great warrior at Troy managed to wound both Aphrodite and Ares? DIOMEDES B1. Who guided Diomedes’ spear against Ares? ATHENA B2.Who was Aphrodite trying to protect when Diomedes injured her? AENEAS 4. Differentiate in meaning between rēgīna and rēgia. RĒGĪNA MEANS QUEEN; RĒGIA MEANS PALACE B1. Differentiate in meaning between volo, velle and volo, volare. VOLLE MEANS TO WANT/WISH; VOLARE MEANS TO FLY B2. Differentiate in meaning between quīdam and quidem. QUĪDAM MEANS A CERTAIN/SOMEONE; QUIDEM MEANS INDEED 5. Translate the following sentence into Latin: “I was sleeping under the tree.” DORMIĒBAM SUB ARBORE B1. Translate the following sentence into Latin: “Who spoke before you?” QUIS ANTE TĒ DĪXIT/DICĒBAT B2. Translate the following sentence into Latin using a participle: “I hear you singing.” AUDIŌ TĒ CANENTEM/CANTANTEM 6. At which battle of 202 BCE did Scipio Africanus achieve final victory over Hannibal, bringing an end to the Second Punic War? ZAMA B1. -

Ancient Roman History Study Guide

Santa Reparata International School of Art Academic Year 2017/2018, Fall 2017 Etruscan and Ancient Roman Civilizations prof. Lorenzo Pubblici Ph.D. Midterm Study Guide 1.The Etruscans: Italy 9th-5th centuries BC • The Villanovan civilization: • Early Iron Age, 9th-8th centuries BC, the Villanovan culture characterized all the Tyrrhenian Etruria, Emilia Romagna (particularly the area of Bologna and Rimini), Marche, Campania and Lucania (see map. 1) • Between Tuscany, Latium, Emilia, and some areas of Campania and the Po Valley, the Villanovan settlements are thick: one every 5-15km, on every hill that could be well defended, near water sources, smaller settlements along the coasts and the Apennines mounts. Map. 1 • 9th century: Villanovan settlements are well distributed in Central Italy, homogenous from a material point of view. • Oldest mention of the Villanovan civilization is in Hesiod, Teogonia (8-7th centuries BC): Tutti i popoli illustri della Tirrenia: all the non-Greek peoples of Italy . • Earlier inscriptions show an oriental alphabet, influenced by the Greeks. • A slow, progressive process of consolidation in the Italian Peninsula What we know about the Villanovan and their relation to the Etruscans It’s very hard to name a “civilization”, an ethnic group, the Villanovans, since all we know from them is from archaeological findings, their material culture. • We know that there were local cultures spread in Italy, basically nomads between the bronze (circa BC3500-1200) and the iron age (circa BC12th-8th centuries). • The earlier unions of peoples that we call Villanovan, arise in these centuries. Particularly along the Tuscan coasts, because they were very rich of iron and minerals, in fact the Villanova, such as the early Etruscans, were merchant civilizations. -

Rome: Village to Republic the Rise and Fall of Roman Civilization Series

Rome: Village to Republic The Rise and Fall of Roman Civilization Series Subject Areas: Social Studies, World History, World Geography and Cultures, Ancient Civilizations Synopsis: ROME: VILLAGE TO REPUBLIC explores the birth of the Roman Empire, from Romulus and Remus, to the Romans’ rebellion against their Etruscan rulers. Students will see how the American Founding Fathers used Rome as a model for another new republic. This is also a story of the city as it grew from a primitive village into a republic based upon the most formidable system the Western world has ever known: democracy. Learning Objectives: Objective 1) Students will identify cultural characteristics of the Romans, Etruscans and Americans. They will identify how their belief systems influenced their choices and how each accommodated the other’s beliefs. Objective 2) Students will identify what it meant to be a Roman citizen and compare and contrast that to what it means to be an American citizen. They will evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each definition. Vocabulary: superpower, descendant, exotic, uncharted, subterranean, primitive, auger, fugitives, province, treachery, intrigue, paranoia, decadence, smoldered, virtue, republic, legions, brunt, idealism, skirmish, empire, muster, laurels, tumult, factions, idealism, forum, defame, strife, vagrants, fugitives, proportion, senate, census, republic, honor, momentous, liberty, codified, envoy, ransacked Pre-Viewing Activities: Choose one objective and direct students to do the following during the program. 1) Have students make a list with words that describe the culture and/or belief systems of the Romans, Etruscans, and Americans. (You may also consider using the Gauls as another category). 2) Have students make a list of words that describe what citizenship meant for the Romans and what it means for Americans. -

The Etruscan Monarchy: Kings of Rome (753509 Bce)

THE ETRUSCAN MONARCHY: KINGS OF ROME (753509 BCE) When Rome began, kings usually ruled citystates Romulus ruled as the first king of Rome 753715 BC ● He populated Roman with fugitives and gave them wives abducted from the Sabine Tribe ● Was said to have vanished in a thunderstorm and later worshipped as the god Quirinus ● Known as a warrior king who developed Rome’s first army Numa Pompilius was a Sabine and ruled as the second king in 715673 BC ● Succeeded Romulus ● Numa was traditionally celebrated by the Romans for his wisdom and piety. ● He was said to have a direct and personal connection with a bunch of deities. ● One of Numa's first acts was the construction of a temple of Janus as a symbol of peace and war. ● Credited with the foundation of most Roman Religious Rites Tullus Hostilius was the successor of Pompilius as the third King from 672641 BC ● Completely different and opposite from his predecessor ● Region consisted mainly of expansion ● Destructed the rival city of Alba Longa ● Plagued a city ● Had a warlike behavior and a complete neglect for Roman Gods ● Asked for help from an angered Jupiter and apparently was struck down by lightning Ancus Marcius was the fourth king and the grandson of Numa Pompilius ● Built Rome’s first prison ● Annexed the Latin tribes ● reformed the Roman religion and ordered the Pontifex Maximus to write down all the traditions and rules of their religion ● His work was kept by future monarchs Lucius Tarquinius Priscus was the fifth king ● His name was originally Lucumo and he was the son of a foreigner ● He was married to a woman named Tanaquil who was unhappy with his social status.