BBC Four As “A Place to Think”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BBC 4 Listings for 14 – 20 January 2017 Page 1 of 4

BBC 4 Listings for 14 – 20 January 2017 Page 1 of 4 SATURDAY 14 JANUARY 2017 The film tells the story of Elvis Costello - a childhood under the lesser-known details of the 1605 attempted attack. For example, influence of his father Ross McManus, the singer with Joe Guy Fawkes was discovered not just once but twice. Also the SAT 19:00 Timeshift (b00x7c3z) Loss's popular dance band; a Catholic education which has amount of gunpowder is thought to have been far more than Series 10 clearly marked him deeply; his overnight success with The was required. Another strange side to gunpowder's story is Attractions and subsequent disenchantment with the formatted revealed - the saltpetre men. Gunpowder requires three The Golden Age of Coach Travel pressures of the music business; a disillusionment which led ingredients - charcoal, sulphur and saltpetre. In the 17th century him to reinvent himself a number of times; and writing and chemistry was primitive. Saltpetre or potassium nitrate forms Documentary which takes a glorious journey back to the 1950s, recording songs in various styles, including country, jazz, soul from animal urine and the saltpetre men would collect soil when the coach was king. From its early origins in the and classical. where animals had urinated. This meant they dug up dovecots, charabanc, the coach had always been the people's form of stables and even people's homes. They had sweeping powers to transport. Cheaper and more flexible than the train, it allowed The film focuses in particular on his collaborations with Paul come onto people's property and take their soil. -

Jack TIM MERRY Puts a Brave Face Plays on Things with It Pool � Comic Lips

18 DAILY STAR, Monday, September 17, 2018 DAILY STAR, Monday, September 17, 2018 19 Pixie NO LAUGHING Pictures: MATTER: Jack TIM MERRY puts a brave face plays on things with it pool comic lips PIXIE Lott sizzles in a pink bikini as she soaks up the sun on the last day of her hen do in Corfu. Fresh from a cooling dip, the 27-year-old showed off her well-tanned curves ahead of her upcoming marriage to model Oliver Cheshire, 30. Kneeling in the water ‘ of her plush villa’s pool on the Greek island, the stunning singer seductively smiles for the ‘ camera. SMILES BETTER: Above, with Kerry Godliman in sitcom Bad Move. Below, in Lead Balloon ISIS LAGS IN BIBLE CLASS ISLAMISTRIGBY inmates tried to hijack prison byRANT PAUL DONNELLEY Bible classes by declaring their support for Lee Rigby’s murderers and Islamic State. “My colleagues couldn’t take any more,” Pastor Paul Song claims the extremists he said. “At times inmates openly spoke regularly interrupted his sermons at in the chapel in support of Islamic State Brixton jail in south London. and suicide bombers. He said the intimidation forced other “And there was nothing I could do NEXT time you’re stuck already know the whole thing’s a stand-up, like the worst possible fi nds Steve rather less restrained. pleased to report. I ask if he badly it could go. It could be the course. Which brings us neatly back clergymen out, while inmates were forced about it. They spoke with such hatred of in a tailback on a country mistake…” version of Jack’s true self. -

Managing the BBC's Estate

Managing the BBC’s estate Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 3 December 2014 BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION Managing the BBC’s estate Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 3 December 2014 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media & Sport by Command of Her Majesty January 2015 © BBC 2015 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. BBC Trust response to the National Audit Office value for money study: Managing the BBC’s estate This year the Executive has developed a BBC Trust response new strategy which has been reviewed by As governing body of the BBC, the Trust is the Trust. In the short term, the Executive responsible for ensuring that the licence fee is focused on delivering the disposal of is spent efficiently and effectively. One of the Media Village in west London and associated ways we do this is by receiving and acting staff moves including plans to relocate staff upon value for money reports from the NAO. to surplus space in Birmingham, Salford, This report, which has focused on the BBC’s Bristol and Caversham. This disposal will management of its estate, has found that the reduce vacant space to just 2.6 per cent and BBC has made good progress in rationalising significantly reduce costs. -

TV Preview: Tales of Television Centre at BFI Southbank / Tue 15 May / 18:10

PRESS RELEASE April 2012 12/29 TV Preview: Tales of Television Centre At BFI Southbank / Tue 15 May / 18:10 BFI Southbank is delighted to present a preview screening of Tales of Television Centre, the upcoming feature-length documentary telling the story of one of Britain’s most iconic buildings as the BBC prepares to leave it. The screening will be introduced by the programme’s producer-director Richard Marson The story is told by both staff and stars, among them Sir David Frost, Sir David Attenborough, Dame Joan Bakewell, Jeremy Paxman, Sir Terry Wogan, Esther Rantzen, Angela Rippon, Biddy Baxter, Edward Barnes, Sarah Greene, Waris Hussein, Judith Hann, Maggie Philbin, John Craven, Zoe and Johnny Ball and much loved faces from Pan’s People (Babs, Dee Dee and Ruth) and Dr Who (Katy Manning, Louise Jameson and Janet Fielding). As well as a wealth of anecdotes and revelations, there is a rich variety of memorable, rarely seen (and in some cases newly recovered) archive material, including moments from studio recordings of classic programmes like Vanity Fair, Till Death Us Do Part, Top of the Pops and Dr Who, plus a host of vintage behind-the-scenes footage offering a compelling glimpse into this wonderful and eccentric studio complex – home to so many of the most celebrated programmes in British TV history. Press Contacts: BFI Southbank: Caroline Jones Tel: 020 7957 8986 or email: [email protected] Lucy Aronica Tel: 020 7957 4833 or email: [email protected] NOTES TO EDITORS TV Preview: Tales of Television Centre Introduced by producer-director Richard Marson BBC 2012. -

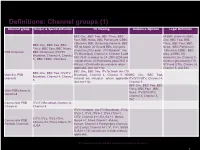

PSB Report Definitions

Definitions: Channel groups (1) Channel group Output & Spend definition TV Viewing Audience Opinion Legal Definition BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC All BBC channels (BBC Four, BBC News, BBC Parliament, CBBC, One, BBC Two, BBC CBeebies, BBC streaming channels, BBC Three, BBC Four, BBC BBC One, BBC Two, BBC HD (to March 2013) and BBC Olympics News , BBC Parliament Three, BBC Four, BBC News, channels (2012 only). ITV Network* (inc ,CBeebies, CBBC, BBC PSB Channels BBC Parliament, ITV/ITV ITV Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5 and Alba, all BBC HD Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel S4C (S4C is added to C4 2008-2009 and channels), the Channel 3 5,, BBC CBBC, CBeebies excluded from 2010 onwards post-DSO in services (provided by ITV, Wales). HD variants are included where STV and UTV), Channel 4, applicable (but not +1s). Channel 5, and S4C. BBC One, BBC Two, ITV Network (inc ITV BBC One, BBC Two, ITV/ITV Main five PSB Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5. HD BBC One, BBC Two, Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel channels variants are included where applicable ITV/STV/UTV, Channel 4, 5 (but not +1s). Channel 5 BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC Four , BBC Main PSB channels News, ITV/STV/UTV, combined Channel 4, Channel 5, S4C Commercial PSB ITV/ITV Breakfast, Channel 4, Channels Channel 5 ITV+1 Network (inc ITV Breakfast) , ITV2, ITV2+1, ITV3, ITV3+1, ITV4, ITV4+1, CITV, Channel 4+1, E4, E4 +1, More4, CITV, ITV2, ITV3, ITV4, Commercial PSB More4 +1, Film4, Film4+1, 4Music, 4Seven, E4, Film4, More4, 5*, Portfolio Channels 4seven, Channel 4 Paralympics channels 5USA (2012 only), Channel 5+1, 5*, 5*+1, 5USA, 5USA+1. -

7116-A BBC TV Review

Independent Review of the BBC’s Digital Television Services 1 Contents Executive Summary 2 1. Introduction 13 1.1 Background, terms of reference, and report structure 13 1.2 General and specific approval conditions 16 1.3 Review process 16 1.4 Consultation results 17 1.5 Conceptual framework: net public value 19 1.6 The BBC’s digital TV strategy and its assumptions about audience behaviour 23 1.7 Television is a mass medium, not a niche medium 26 2. Performance Against the Approval Conditions 35 2.1 CBeebies 35 2.2 CBBC 37 2.3 BBC3 41 2.4 BBC4 47 2.5 Interactivity 50 2.6 Driving digital takeup 52 2.7 Value for money 54 2.8 Performance against conditions: summary and conclusions 58 3. Market Impact 63 3.1 Introduction 63 3.2 In what ways might the BBC’s services impact the market? 65 3.3 Clarifying the “base case” 66 3.4 Direct impact on commercial channels’ revenue 69 3.5 Impact on programme supply market 77 3.6 Impact on long-run competitiveness of the market 79 3.7 Market impact: summary and conclusions 80 4. How Might the Services Develop in the Future? 82 4.1 Summary of conclusions: performance and market impact 82 4.2 The evolving market context and the BBC-TV portfolio 87 4.3 Recommendations for future development 91 Appendix: Ofcom Analysis of Genre Mix 98 Supplementary Reports* Report on CBeebies and CBBC, by Máire Messenger Davies Report on BBC3 and BBC4, by Steve Hewlett Assessment of the Market Impact of the BBC’s New Digital TV and Radio Services, by Ofcom About the Author 100 *All supplementary reports are available electronically on the DCMS website, www.culture.gov.uk 2 Independent Review of the BBC’s Digital Television Services Executive Summary This report reviews the BBC’s digital television services CBeebies, CBBC, BBC3 and BBC4. -

The True Story of Mission to Hell Page 4

The newspaper for BBC pensioners – with highlights from Ariel online The true story of Mission to Hell Page 4 August 2015 • Issue 4 Trainee Oh! What operators a lovely reunite – Vietnam War TFS 1964 50 years on Page 6 Page 8 Page 12 NEWS • MEMORIES • CLASSIFIEDS • YOUR LETTERS • OBITUARIES • CROSPERO 02 BACK AT THE BBC Departments Annual report highlights ‘better’ for BBC challenge move to Salford The BBC faces a challenge to keep all parts of the audience happy at the same time as efficiency targets demand that it does less. said that certain segments of society were more than £150k and to trim the senior being underserved. manager population to around 1% of But this pressing need to deliver more and the workforce. in different ways comes with a warning that In March this year, 95 senior managers Delivering Quality First (DQF) is set to take a collected salaries of more than £150k against bigger bite of BBC services. a target of 72. The annual report reiterates that £484m ‘We continue to work towards these of DQF annual savings have already been targets but they have not yet been achieved,’ achieved, with the BBC on track to deliver its the BBC admitted, attributing this to ‘changes Staff ‘loved the move’ from London to target of £700m pa savings by 2016/17. in the external market’ and the consolidation Salford that took place in 2011 and The first four years of DQF have seen of senior roles into larger jobs. departments ‘are better for it’, believes Peter Salmon (pictured). a 25% reduction in the proportion of the More staff licence fee spent on overheads, with 93% of Speaking four years on from the biggest There may be too many at the top, but the the BBC’s ‘controllable spend’ now going on ever BBC migration, the director, BBC gap between average BBC earnings and Tony content and distribution. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

1 BBC Four Biopics

BBC Four biopics: Lessons in Trashy Respectability The broadcast of Burton and Taylor in July 2013 marked the end of a decade- long cycle of feature-length biographical dramas transmitted on BBC Four, the niche arts and culture digital channel of the public service broadcaster. The subjects treated in these biopics were various: political figures, famous cooks, authors of popular literature, comedians and singers. The dramas focused largely on the unhappy or complex personal lives of well-loved figures of British popular culture. From the lens of the 21st century, these dramas offered an opportunity for audiences to reflect on the culture and society of the 20th century, changing television’s famous function of ‘witness’ to one of ‘having witnessed’ and/or ‘remembering’ (Ellis, 2000). The programmes function as nostalgia pieces, revisiting personalities familiar to the anticipated older audience of BBC Four, working in concert with much of the archive and factual content on the digital broadcaster’s schedules. However, by revealing apparent ‘truths’ that reconfigure the public images of the figures they narrate, these programmes also undermine nostalgic impulses, presenting conflicting interpretations of the recent past. They might equally be seen as impudent incursions onto the memory of the public figures, unnecessarily exposing the real-life subjects to censure, ridicule or ex post facto critical judgement. Made thriftily on small budgets, the films were modest and spare in visual style but were generally well received critically, usually thanks to writerly screenplays and strong central performances. The dramas became an irregular but important staple of the BBC Four schedule, furnishing the channel with some of their highest ratings in a history chequered by low audience numbers. -

HD Digital Box GFSAT200HD/A Instruction Manual Welcome to Your

HD Digital Box GFSAT200HD/A Instruction Manual Welcome to your new freesat+ HD digital TV recorder Now you can pause, rewind and record both HD and SD television, and so much more Goodmans GFSAT200HD-A_IB_Rev2_120710.indd 1 12/07/2010 14:11:18 Welcome Thank you for choosing this Goodmans freesat HD Digital Box. Not only can it receive over 140 subscription free channels, but if you have a broadband service with a minimum speed of 1Mb you can access IP TV services, which you can watch back at a time to suit you. It’s really simple to use; it’s all done using the clear, easy to understand on screen menus which are operated from the remote control. It even has a reminder function so that you won’t miss your favourite programmes. For a one off payment, you can buy a digital A digital box lets you access digital channels box, satellite dish and installation giving you that are broadcast in the UK. It uses a digital over 140 channels covering the best of TV signal, received through your satellite dish and more. and lets you watch it through your existing television. This product is capable of receiving and This product has a HDMI connector so that decoding Dolby Digital Plus. you can watch high definition TV via a HDMI lead when connected to a HD Ready TV. Manufactured under license from Dolby HDMI, the HDMI logo and High-Definition Laboratories. Dolby and the double-D symbol Multimedia Interface are trademarks or are trademarks of Dolby Laboratories. -

The BBC's Use of Spectrum

The BBC’s Efficient and Effective use of Spectrum Review by Deloitte & Touche LLP commissioned by the BBC Trust’s Finance and Strategy Committee BBC’s Trust Response to the Deloitte & Touche LLPValue for Money study It is the responsibility of the BBC Trust,under the As the report acknowledges the BBC’s focus since Royal Charter,to ensure that Value for Money is the launch of Freeview on maximising the reach achieved by the BBC through its spending of the of the service, the robustness of the signal and licence fee. the picture quality has supported the development In order to fulfil this responsibility,the Trust and success of the digital terrestrial television commissions and publishes a series of independent (DTT) platform. Freeview is now established as the Value for Money reviews each year after discussing most popular digital TV platform. its programme with the Comptroller and Auditor This has led to increased demand for capacity General – the head of the National Audit Office as the BBC and other broadcasters develop (NAO).The reviews are undertaken by the NAO aspirations for new services such as high definition or other external agencies. television. Since capacity on the platform is finite, This study,commissioned by the Trust’s Finance the opportunity costs of spectrum use are high. and Strategy Committee on behalf of the Trust and The BBC must now change its focus from building undertaken by Deloitte & Touche LLP (“Deloitte”), the DTT platform to ensuring that it uses its looks at how efficiently and effectively the BBC spectrum capacity as efficiently as possible and uses the spectrum available to it, and provides provides maximum Value for Money to licence insight into the future challenges and opportunities payers.The BBC Executive affirms this position facing the BBC in the use of the spectrum. -

Putney Sofka Zinovieff

AUGUST 2018 Putney Sofka Zinovieff From the acclaimed author comes a brilliant, challenging novel about a bohemian family in 1970s London and the consequences of a taboo relationship Sales points • Sofka Zinovieff 's previous books have received widespread critical acclaim. Her most recent, The Mad Boy, Lord Berners, My Grandmother and Me was a New York Times Editors ' Choice, 2015. Putney will have a major publicity campaign, including masses of author interviews and events. • Sensitively exploring a taboo subject (a sexual relationship between a child and an adult), this novel is a perfect book club read. • Will appeal to fans of Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov, The Line of Beauty by Alan Hollinghurst, Never Mind by Edward St Aubyn and Diary of a Teenage Girl by Phoebe Gloeckner. Description From the acclaimed author comes a brilliant, challenging novel about a bohemian family in 1970s London and the consequences of a taboo relationship Ralph Boyd 's first glimpse of 9 year-old Daphne will be etched on his mind forever. Dark, teasing, slippery as mercury, she seems neither boy nor girl, but sprite something elemental. An up-and-coming composer, Ralph is visiting the writer Edmund Greenslay at his riverside home in Putney to discuss a collaboration. In its colourful rooms and unruly garden, Ralph finds an intoxicating world of sensuous ease and bohemian abandon that captures the mood of the moment. Entranced, he knows he will return. But Ralph is twenty-five and Daphne is only a child, and even in the liberal 1970s a fast-burgeoning relationship between a man and his friend 's daughter must be kept secret.