Colonic Ischemia 9/21/14, 9:02 PM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Irritable Bowel Syndrome Similarities and Differences 2 www.ccfa.org IBD Help Center: 888.MY.GUT.PAIN 888.694.8872 Important Differences Between IBD and IBS Many diseases and conditions can affect the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which is part of the digestive system and includes the esophagus, stomach, small intestine and large intestine. These diseases and conditions include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). IBD Help Center: 888.MY.GUT.PAIN 888.694.8872 www.ccfa.org 3 Inflammatory bowel diseases are a group of inflammatory conditions in which the body’s own immune system attacks parts of the digestive system. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Inflammatory bowel diseases are a group of inflamma- Causes tory conditions in which the body’s own immune system attacks parts of the digestive system. The two most com- The exact cause of IBD remains unknown. Researchers mon inflammatory bowel diseases are Crohn’s disease believe that a combination of four factors lead to IBD: a (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). IBD affects as many as 1.4 genetic component, an environmental trigger, an imbal- million Americans, most of whom are diagnosed before ance of intestinal bacteria and an inappropriate reaction age 35. There is no cure for IBD but there are treatments to from the immune system. Immune cells normally protect reduce and control the symptoms of the disease. the body from infection, but in people with IBD, the immune system mistakes harmless substances in the CD and UC cause chronic inflammation of the GI tract. CD intestine for foreign substances and launches an attack, can affect any part of the GI tract, but frequently affects the resulting in inflammation. -

Twisted Bowels: Intestinal Obstruction Blake Briggs, MD Mechanical

Twisted Bowels: Intestinal obstruction Blake Briggs, MD Objectives: define bowel obstructions and their types, pathophysiology, causes, presenting signs/symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options, as well as the complications associated with them. Bowel Obstruction: the prevention of the normal digestive process as well as intestinal motility. 2 overarching categories: Mechanical obstruction: More common. physical blockage of the GI tract. Can be complete or incomplete. Complete obstruction typically is more severe and more likely requires surgical intervention. Functional obstruction: diffuse loss of intestinal motility and digestion throughout the intestine (e.g. failure of peristalsis). 2 possible locations: Small bowel: more common Large bowel All bowel obstructions have the potential risk of progressing to complete obstruction Mechanical obstruction Pathophysiology Mechanical blockage of flow à dilation of bowel proximal to obstruction à distal bowel is flattened/compressed à Bacteria and swallowed air add to the proximal dilation à loss of intestinal absorptive capacity and progressive loss of fluid across intestinal wall à dehydration and increasing electrolyte abnormalities à emesis with excessive loss of Na, K, H, and Cl à further dilation leads to compression of blood supply à intestinal segment ischemia and resultant necrosis. Signs/Symptoms: The goal of the physical exam in this case is to rule out signs of peritonitis (e.g. ruptured bowel). Colicky abdominal pain Bloating and distention: distention is worse in distal bowel obstruction. Hyperresonance on percussion. Nausea and vomiting: N/V is worse in proximal obstruction. Excessive emesis leads to hyponatremic, hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis with hypokalemia. Dehydration from emesis and fluid shifts results in dry mucus membranes and oliguria Obstipation: severe constipation or complete lack of bowel movements. -

A Case Report of Fibro-Stenotic Crohn's Disease in the Middle

DOI: https://doi.org/10.22516/25007440.185 Case report A Case Report of Fibro-Stenotic Crohn’s Disease in the Middle Ileum as the Initial Manifestation Adriana Margarita Rey,1 Gustavo Reyes,1 Fernando Sierra,1 Rafael García-Duperly,2 Rocío López,3 Leidy Paola Prada.4 1 Gastroenterologist in the Gastroenterology and Abstract Hepatology Service of the Hospital Universitario Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá in Bogotá, Colombia Crohn’s disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease that can affect the entire gastrointestinal tract. The small 2 Colon and Rectum Surgeon in the Department of intestine is affected in about 50% of patients among whom the terminal ileum is the area most commonly affected. Surgery of the Hospital Universitario Fundación Intestinal stenosis is a common complication in CD and approximately 30% to 50% of patients present Santa Fe de Bogotá in Bogotá, Colombia 3 Pathologist at of the Hospital Universitario Fundación stenosis or penetrating lesions at the time of diagnosis. Because conventional endoscopic techniques do not Santa Fe de Bogotá and Professor at Universidad de allow evaluation of small bowel lesions, techniques such as enteroscopy and endoscopic video-capsule were los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia developed. Each has advantages and indications. 4 Third Year Internal Medicine Resident at the Hospital Universitario Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá in We present the case of a patient with CD with localized fibrostenosis in the middle ileum which is not a Bogotá, Colombia frequent site for this type of lesion. Author for correspondence: Adriana Margarita Rey. Bogotá D.C. Colombia [email protected] Keywords ........................................ -

Adult Intussusception

1 Adult Intussusception Saulius Paskauskas and Dainius Pavalkis Lithuanian University of Health Sciences Kaunas Lithuania 1. Introduction Intussusception is defined as the invagination of one segment of the gastrointestinal tract and its mesentery (intussusceptum) into the lumen of an adjacent distal segment of the gastrointestinal tract (intussuscipiens). Sliding within the bowel is propelled by intestinal peristalsis and may lead to intestinal obstruction and ischemia. Adult intussusception is a rare condition wich can occur in any site of gastrointestinal tract from stomach to rectum. It represents only about 5% of all intussusceptions (Agha, 1986) and causes 1-5% of all cases of intestinal obstructions (Begos et al., 1997; Eisen et al., 1999). Intussusception accounts for 0.003–0.02% of all hospital admissions (Weilbaecher et al., 1971). The mean age for intussusception in adults is 50 years, and and the male-to-female ratio is 1:1.3 (Rathore et. al., 2006). The child to adult ratio is more than 20:1. The condition is found in less than 1 in 1300 abdominal operations and 1 in 100 patients operated for intestinal obstruction. Intussusception in adults occurs less frequently in the colon than in the small bowel (Zubaidi et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007). Mortality for adult intussusceptions increases from 8.7% for the benign lesions to 52.4% for the malignant variety (Azar & Berger, 1997) 2. Etiology of adult intussusception Unlike children where most cases are idiopathic, intussusception in adults has an identifiable etiology in 80- 90% of cases. The etiology of intussusception of the stomach, small bowel and the colon is quite different (Table 1). -

Recognizing-Consitpation-And-Bowel

Hughes Melton, MD Post Office Box 1797 Commissioner Richmond, Virginia 23218-1797 Office of Integrated Health Health & Safety Information Dr. Dawn M. Adams DNP, ANP-BC, CHC Director, Office of Integrated Health Recognizing Constipation & Preventing Bowel Obstruction 2018 Recognizing Constipation Constipation is a disorder that occurs when bowel movements become difficult or less frequent is frequently seen in many people. Individuals with developmental disabilities often have problems with chronic constipation as a result of but not limited to: Medication side effects Neuromuscular problems related to the person's disability Signs of Constipation small infrequent bowel movements hemorrhoids due to straining with bowel movements increased abdominal girth abdominal pain Chronic constipation Chronic constipation must be addressed in all individuals. This can often be a silent problem, especially for individuals who are independent in toileting activities. Without treatment, chronic constipation can lead to bowel obstruction, bowel perforation and death. Bowel Obstruction (Intestinal Obstruction) A partial or complete block of the small or large intestine that keeps food, liquid, gas, and stool from moving through the intestines in a normal way. October 2018 Hughes Melton, MD Post Office Box 1797 Commissioner Richmond, Virginia 23218-1797 Bowel obstructions may be caused by a twist in the intestines. Intestines are called the gut. The large intestine includes the appendix, cecum, colon, and rectum and is 5 feet long. It absorbs water from stool and changes it from a liquid to a solid form. The small intestine is where most digestion occurs. It measures about 20 feet and includes the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. o Digestion is the process of breaking down food into substances the body can use for energy, tissue growth, and repair. -

Jejunoileal Diverticulitis: Big Trouble in Small Bowel

Jejunoileal Diverticulitis: Big Trouble in Small Bowel MICHAEL CARUSO DO, HAO LO MD EMERGENCY RADIOLOGY, UMASS MEMORIAL MEDICAL CENTER, WORCESTER, MA LEARNING OBJECTIVES: After excluding Meckel’s diverticulum, less than 30% of reported diverticula occurred in the CASE 1 1. Be aware of the relatively rare diagnoses of jejunoileal jejunum and ileum. HISTORY: 52 year old female with left upper quadrant pain. diverticulosis (non-Meckelian) and diverticulitis. Duodenal diverticula are approximately five times more common than jejunoileal diverticula. FINDINGS: 2.2 cm diverticulum extending from the distal ileum with adjacent induration of the mesenteric fat, consistent with an ileal diverticulitis. 2. Learn the epidemiology, pathophysiology, imaging findings and differential diagnosis of jejunoileal diverticulitis. Diverticulaare sac-like protrusions of the bowel wall, which may be composed of mucosa and submucosa only (pseudodiverticula) or of all CT Findings (2) layers of the bowel wall (true . Usually presents as a focal area of bowel wall thickening most prominent on the mesenteric side of AXIAL AXIAL CORONAL diverticula) the bowel with adjacent inflammation and/or abscess formation . Diverticulitis is the result of When abscess is present, CT findings may include relatively smooth margins, areas of low CASE 2 obstruction of the neck of the attenuation within the mass, rim enhancement after IV contrast administration, gas within the HISTORY: 62 year old female with epigastric and left upper quadrant pain. diverticulum, with subsequent mass, displacement of the surrounding structures, and edema of thickening of the surrounding fat inflammation, perforation and or fascial planes FINDINGS: 4.7 cm diameter out pouching seen arising from the proximal small bowel and associated with adjacent inflammatory stranding. -

Ischaemic Colitis: Practical Challenges and Evidence-Based Recommendations For

Ischaemic Colitis: Practical Challenges and Evidence-Based Recommendations for Management Alexander Hung1*, Tom Calderbank1*, Mark A Samaan1, Andrew A Plumb2, George Webster1 Author affiliations 1Department of Gastroenterology, University College London Hospitals, London, UK 2Department of Radiology, University College London Hospitals, London, UK *Authors contributed equally Correspondence to Mark A Samaan Department of Gastroenterology University College London Hospitals 250 Euston Road London NW1 2PG [email protected] Running title Ischaemic Colitis Management Word count 3212 Key Words Ischaemic colitis, colonic ischaemia ABSTRACT Ischaemic colitis (IC) is a common condition with rising incidence and, in severe cases, a high mortality rate. Its presentation, severity and disease behaviour can vary widely and there exists significant heterogeneity in treatment strategies and resultant outcomes. In this article we explore practical challenges in the management of IC and where available, make evidence-based recommendations for its management based on a comprehensive review of available literature. An optimal approach to initial management requires early recognition of the diagnosis followed by prompt and appropriate investigation. Ideally, this should involve the input of both gastroenterology and surgery. CT with intravenous and oral contrast is the imaging modality of choice. It can support a clinical diagnosis, define the severity and distribution of ischaemia and has prognostic value. In all but fulminant cases, this should be followed (within 48 hours) by lower GI endoscopy to reach the distal-most extent of the disease, providing endoscopic (and histological) confirmation. The mainstay of medical management is conservative/supportive treatment, with bowel rest, fluid resuscitation and antibiotics. Specific laboratory, radiological and endoscopic features are recognised to correlate with more severe disease, higher rates of surgical intervention and ultimately worse outcomes. -

Coping with the Problems of Diagnosis of Acute Colitis

Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging (2013) 94, 793—804 . CONTINUING EDUCATION PROGRAM: FOCUS . Coping with the problems of diagnosis of acute colitis a,∗,c b a E. Delabrousse , F. Ferreira , N. Badet , a b M. Martin , M. Zins a Urinogenital and Digestive Imaging Department, hôpital Jean-Minjoz, CHRU de Besanc¸on, 3, boulevard Fleming, 25030 Besanc¸on, France b Radiology Department, hôpital Saint-Joseph, 184, rue Raymond-Losserand, 75014 Paris, France c EA 4662, Nanomedicine Laboratory, Imagery and Therapeutics, University of Franche-Comté, Besanc¸on, France KEYWORDS Abstract Acute colitis is an acute condition of the colon. For the radiologist, it is mainly Colitis; diagnosed during differential diagnosis of acute abdominal conditions. There are many causes Ischaemia; of colitis and the degree of its severity varies. A CT scan is the best imaging examination for IBD; diagnosing it and also for analysing and characterising colitis. The topography, type of lesion Pseudomembranous; and associated factors can often suggest a precise diagnosis but it is nevertheless essential to Neutropenia integrate these findings into the clinical context and take laboratory values into account. The use of endoscopy is still the rule where a doubt remains, or to obtain necessary histological evidence. © 2013 Éditions françaises de radiologie. Published by Elsevier Masson SAS. All rights reserved. Acute colitis is an acute condition of the colon and most often presents in the form of an acute abdominal picture with very variable clinical symptoms and laboratory test results. The most frequent symptoms encountered in colitis are abdominal pain, fever and diarrhoea [1]. Hyperleucocytosis and elevated CRP in laboratory tests are common. -

Patient Selection Criteria

M∙ACS MACS Patient Selection Criteria The objective is to screen, on a daily basis, the Acute Care Surgical service “touches” at your hospital to identify patients who meet criteria for further data entry. The specific patient diseases/conditions that we are interested in capturing for emergent general surgery (EGS) are: 1. Acute Appendicitis 2. Acute Gallbladder Disease a. Acute Cholecystitis b. Choledocholithiasis c. Cholangitis d. Gallstone Pancreatitis 3. Small Bowel Obstruction a. Adhesive b. Hernia 4. Emergent Exploratory Laparotomy (Refer to the ex-lap algorithm under the Diseases or Conditions section below for inclusion/exclusion criteria.) The daily census for patients admitted to the Acute Care Surgery Service or seen as a consult will have to be screened. There may be other sources to accomplish this screening such as IT and we are interested in learning about these sources from you. From this census, a list can be compiled of patients with the aforementioned diseases/conditions. The first level of data entry involves capture and entry of the patient into the MACS Qualtrics database. All patients with the identified diseases/conditions will have data entered regardless of whether or not they received an operation during admission/ED visit. The second level of data entry takes place if an existing MACS patient returns to the hospital (ED or admission) or has outcome events identified within the 30-day post-operative time frame if the patient had surgery, or within 30 days from discharge for the non-operative patients. You will see that we are capturing diagnostic, interventional, and therapeutic data that extend beyond what is typically captured for MSQC patients. -

Ischemic Colitis Caused by Polycythemia Vera: a Case Report and Literature Review

EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 16: 3663-3667, 2018 Ischemic colitis caused by polycythemia vera: A case report and literature review SHASHA ZHANG1, RUIXUE LAI1, XUEQING GAO1, YUFEI ZHAO1, YUE ZHAO2, JIANHUA WU3 and ZHANJUN GUO1 Departments of 1Rheumatology and Immunology, and 2Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 3Animal Center, The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, Hebei 050011, P.R. China Received January 16, 2018; Accepted August 10, 2018 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2018.6638 Abstract. Polycythemia vera (PV) is a chronic myeloproliferative Ischemic colitis (IC) can be described as an ischemic disease disorder originating from hematopoietic stem cells and of the colon, which results from decreased blood flow due to complicated by thrombosis and bleeding. This report describes a various causes that leads to intestinal wall ischemia, injury or case of ischemic colitis (IC) caused by PV and includes a review necrosis (3). The risk factors for IC mainly include diabetes, of the relevant literature. The patient was a 59-year-old male hypertension, dyslipidemia, peripheral vascular disease, with a history of PV who presented with abdominal pain and aspirin administration, and digoxin or constipation-inducing hematochezia. Colonoscopy and histopathological examination medications (4). The main clinical manifestations include results indicated suspected ischemic bowel disease. Following abdominal pain, diarrhea, and hematochezia (5). A reliable experimental anticoagulant therapy for 7 days, the patient no diagnosis of IC depends on the comprehensive evaluation of longer experienced abdominal pain and hematochezia had clinical symptoms, biochemical tests, radiological examina- resolved. Colonoscopy review showed no obvious anomalies tions, and endoscopic assessments (6). In certain cases, PV 1 month later. -

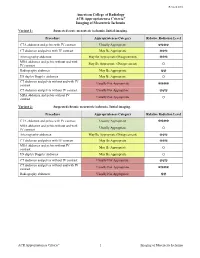

ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Imaging of Mesenteric Ischemia

Revised 2018 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Imaging of Mesenteric Ischemia Variant 1: Suspected acute mesenteric ischemia. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level CTA abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast Usually Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ Arteriography abdomen May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) ☢☢☢ MRA abdomen and pelvis without and with May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) IV contrast O Radiography abdomen May Be Appropriate ☢☢ US duplex Doppler abdomen May Be Appropriate O CT abdomen and pelvis without and with IV Usually Not Appropriate contrast ☢☢☢☢ CT abdomen and pelvis without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ MRA abdomen and pelvis without IV Usually Not Appropriate contrast O Variant 2: Suspected chronic mesenteric ischemia. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level CTA abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast Usually Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ MRA abdomen and pelvis without and with Usually Appropriate IV contrast O Arteriography abdomen May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) ☢☢☢ CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ MRA abdomen and pelvis without IV May Be Appropriate contrast O US duplex Doppler abdomen May Be Appropriate O CT abdomen and pelvis without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT abdomen and pelvis without and with IV Usually Not Appropriate contrast ☢☢☢☢ Radiography abdomen Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢ ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Imaging of Mesenteric Ischemia IMAGING OF MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA Expert Panels on Vascular Imaging and Gastrointestinal Imaging: Michael Ginsburg, MDa; Piotr Obara, MDb; Drew L. Lambert, MDc; Michael Hanley, MDd; Michael L. Steigner, MDe; Marc A. Camacho, MD, MSf; Ankur Chandra, MDg; Kevin J. Chang, MDh; Kenneth L. -

Classic “Outlet” Rectal Bleeding Does Not Require Full Colonoscopy to Exclude Significant Pathology

Classic “Outlet” Rectal Bleeding does not Require Full Colonoscopy to Exclude Significant Pathology ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Eric L. Marderstein, M.D., M.P.H. James M. Church, M.D. Department of Colorectal Surgery, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, Ohio PURPOSE: Full diagnostic colonoscopy often is performed CONCLUSIONS: In patients with classic outlet bleeding, the to exclude significant pathology in patients presenting yield of a complete diagnostic colonoscopy is low. If the with rectal bleeding. In patients with classic “outlet” history is classic for outlet bleeding and no other bleeding, defined as bright red blood after or during indication for colonoscopy exists, flexible sigmoidoscopy defecation, with no family history of colorectal neoplasia is enough to exclude significant pathology. or change in bowel habits, we hypothesize that the diagnostic yield of complete colonoscopy will be low. The purpose of this study was to determine whether complete KEY WORDS: Outlet bleeding; Gastrointestinal bleeding; colonoscopy is necessary in the evaluation of patients with Colonoscopy; Sigmoidoscopy. “outlet” rectal bleeding. METHODS: Information for all patients undergoing colo- olonoscopy is an important diagnostic tool in the noscopy by a single endoscopist was prospectively C workup of a variety of gastrointestinal symptoms. It recorded. Before each colonoscopy, a complete history, is very sensitive for the detection of pathology, resulting including indication for the examination, was obtained. in lower gastrointestinal bleeding, and can be used to 1,2 Using standard definitions, patients with outlet bleeding, provide treatment at the time of the examination. suspicious bleeding, hemorrhage, and occult bleeding Additionally, it has proven effective as a screening exa- were accessed and the findings of their colonoscopies mination for the early diagnosis of colorectal cancer.