4. Education and the Welfare Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Irons ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS BA (Hons.)

John Irons ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS B.A. (hons.), M.A. Modern & Medieval Languages (German, French, Dutch), Cambridge University (1964, 1968) Ph.D. The Development of Imagery in the Poetry of P.C. Boutens (Dutch), Cambridge University (1971) Cand. Mag. English (major subject), Lund University, Sweden German (minor subject), Odense University (1977) Dip. Ed. Oxford University (1965) PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS 1968-1971 Lecturer at Odense University, Denmark 1973-79 External Lecturer at Odense University, Denmark 1974-2007 Lecturer and Senior Lecturer at Odense College of Education, Denmark (English & German) 1987 - Professional translator (from Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Dutch, German and French) 2007 Awarded the NORLA translation prize for non-fiction 2016 Joint Winner of the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize (100 Dutch-Language Poems, Holland Park Press – see below) 2019 Shortlisted for The Bernhard Shaw Prize (translation from the Swedish) 2018 SOME PUBLICATIONS TO DATE Büchmann-Møller, Frank, You Just Fight For Your Life (Biography of Lester Young), Greenwood Press, New York Büchmann-Møller, Frank, You Got To Be Original, Man (Lester Young Solography) Greenwood Press, New York Niels Thomassen. Communicative Ethics in Theory and Practice, (Macmillan, London 1992) Finn Hauberg Mortensen, The Reception of Søren Kierkegaard in Japan, (Odense University Press, 1996) Henrik Reeh, Siegfried Kracauer- the resubjectivisation of urban culture, MIT Press 2005 Lise Funder, Nordic Jewellery, Nyt Nordisk Forlag, 1996 Lise Funder, Dansk Smykkekunst -

Guest Speakers to Explore Augustana's Legacy at Gathering VIII in St. Peter, June 21–24, 2012

TheAugustana Heritage Newsletter Volume 7 Number 3 Fall 2011 Guest speakers to explore Augustana’s legacy at Gathering VIII in St. Peter, June 21–24, 2012 Guest speakers will explore The plenary speakers include: Bishop Antje Jackelén the theme, “A Living of the Diocese of Lund, Church of Sweden, on “The Legacy,” at Gathering VIII Church in Two Secular Cultures: Sweden and America”; of the Augustana Heritage Dr. James Bratt, Professor of Church History at Calvin Association at Gustavus College, Grand Rapids, Michigan, on “Augustana in Adolphus College in St. American Church History”; The Rev. Rafael Malpica Peter, Minnesota, from Padil, executive director of the Global Mission Unit, June 21-24, 2012. Even Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, on “Global though 2012 will mark Missions Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow”. the 50th anniversary of “Augustana: A Theological Tradition” will be the the Augustana Lutheran theme of a panel discussion led by the Rev. Dr. Harold Church’s merger with Skillrud, the Rev. Dr. Dale Skogman and the Rev. Dr. other Lutheran churches Theodore N. Swanson. The Rev. Dr. Arland J. Hultgren after 102 years since its will moderate the discussion. founding by Swedish The Jenny Lind Singer for 2012, a young musician immigrants in 1860, it from Sweden, will give a concert on Saturday evening, continues as a “living June 23. See Page 14 for the tentative schedule for each Bishop Antje Jackelén of legacy” among Lutherans day in what promises to be another wonderful AHA the Church of Sweden today. Gathering. Garrison Keillor, known internationally for the Minnesota Public Radio show “A Prairie Home Companion,” will speak on “Life among the Lutherans,” at the opening session on Thursday, June 21. -

Vem Var Den Anonyme Bordsgästen? Om Namnen I En Stockholmares Kalender För 1830

Vem var den anonyme bordsgästen? Om namnen i en stockholmares kalender för 1830 Bengt af Klintberg r 1883 förvärvade revisorn Ferdinand af tersom de inte hade några barn. De bodde en Klintberg gården Vretaberg i Grödinge sock- tid i England och medförde stora mängder en på Södertörn som sommarbostad åt sin fa- engelskspråkig litteratur när de återvände till milj. Han avled 1908, men hans hustru Ger- Sverige. De nyare böckerna på bokhyllorna trud levde ända till 1931 och tillbringade alla verkar alla ha införskaffats av Eyvor af Klint- somrar fram till sin död på Vretaberg. När berg. dottern Eyvor af Klintberg, näst yngst av tio En av de äldre böckerna väckte min nyfi- systrar, gick i pension från sin tjänst som rek- kenhet. Den är liten och kompakt, inbunden i tor för Lyceum för flickor i Stockholm, flyt- ett vackert brunt helfranskt skinnband med tade hon ut till Vretaberg och bodde där året ryggdekor i guld. Antalet sidor uppgår till runt tills hon avled 1964. Under det dryga mer än 600. På titelbladet kan man läsa att halvsekel som har förflutit sedan dess, har boken är Sveriges och Norriges Calender för gården fungerat som festlokal för Ferdinands året 1830. Utgivare är Kungl. Vetenskapsa- och Gertruds ättlingar, som numera uppgår kademien. Innehållet avviker inte från det till cirka 400. man brukar finna i kalendrar från denna tid Ingen har räknat hur många böcker som och även senare. Där finns astronomiska ta- finns på Vretaberg, men antalet uppgår till åt- beller, bland annat en över ”Stjernors Bort- skilliga tusen. För några år sedan gick jag ige- skymning af Månen”, och förteckningar över kungahus, lantgrevar, hovrättsråd, prostar, nom hela biblioteket och sorterade ut fuktska- riddare av Vasaorden, stiftsjungfrur och dade och illa medfarna volymer. -

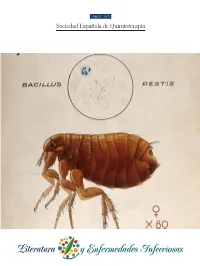

Libro Completo

TOMO 1 - 2021 Sociedad Española de Quimioterapia Editores Contenidos Emma Vázquez-Espinosa Servicio de Neumología, Hospital Universitario La Princesa, Madrid, España 3 Claudio Laganà Una visión histórica, socio- Servicio de Radiodiagnóstico, Hospital Universitario cultural y literaria de casos La Princesa, Madrid de Bacillus anthracis por (España) brochas de afeitar Fernando Vázquez Servicio de Microbiología. Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, España. © Copyright 2021 Sociedad Española de 11 Quimioterapia John Donne, Spanish Reservados todos los derechos. Doctors and the epidemic Queda rigurosamente prohibida, sin la autorización typhus: fleas or lice? escrita del editor, la reproducción parcial o total de esta publicación por cualquier medio o procedimiento, comprendidos la reprografía y el tratamiento informático, y la distribución de ejemplares mediante alquiler o préstamo públicos, bajo las sanciones establecidas por la ley 20 The Spanish flu and the Publicación que cumple los re- fiction literature quisitos de soporte válido Maquetación Vic+DreamStudio Impresión España Esta publicación se imprime en Uno de los más importantes libros escrito, y más citado, es el libro de Susan Sontag: "La enfermedad papel no ácido. This publication is printed in y sus metáforas. El sida y sus metáforas". La enfermedad, y las infecciones en particular, han estado acid free paper. presentes por siglos en las obras de la literatura mundial. Las infecciones aparecen en estas obras en el contexto generalmente del tiempo en que fueron escritas, unas veces de forma anecdótica y LOPD otras formando parte del corpus del libro y el tema tratado. Este libro quiere ser una aproximación a Informamos a los lectores que, este tema en la esperanza de que anime a muchas personas a leer estas obras, y además a entender según lo previsto en el Regla- el contexto en que fueron escritas, con las infecciones que fueron predominantes en cada época mento General de Protección concreta. -

Svenskt Gudstjänstliv Årgång 95 / 2020

Svenskt Gudstjänstliv årgång 95 / 2020 Arbete med psalm: Text, musik, teologi förord 1 2 svenskt gudstjänstliv 2020 Svenskt Gudstjänstliv årgång 95 / 2020 Arbete med psalm: Text, musik, teologi redaktörer Mattias Lundberg · Jonas Lundblad artikelförfattare Per Olof Nisser · Eva Haettner Aurelius · Susanne Wigorts Yngvesson · Mikael Löwegren · Anders Dillmar · Hans Bernskiöld · Anders Piltz Artos förord 3 Laurentius Petri Sällskapet för svenskt gudstjänstliv abonnemang på årsboken svenskt gudstjänstliv Det finns två typer av abonnemang: 1 Medlemmar i Laurentius Petri Sällskapet för svenskt gudstjänstliv (LPS) erhåller årsboken som medlemsförmån samt meddelanden om sällskapets övriga verksam- het. Nya medlemmar är välkomna. Medlemsavgiften är 200 kr. För medlemmar utanför Sverige tillkommer extra distributions kostnader. Inbetalning görs till sällskapets plusgirokonto 17 13 72–6. Kassaförvaltare är kyrkokantor Ing-Mari Johansson, Jung Åsa 9, 535 92 Kvänum. Tel.: 073-917 19 58. E-postadress: [email protected] 2 Abonnemang på enbart årsboken kostar 180 kr för 2020. För abonnenter utanför Sverige tillkommer extra distributionskostnader. Avgiften sätts in på årsbokens plusgirokonto 42 68 84–3, Svenskt Gudstjänstliv. Laurentius Petri Sällskapet för svenskt gudstjänstliv (LPS) Organisationsnummer 89 47 00-7822 Ordförande: TD Anna J. Evertsson, Floravägen 31, 291 43 Kristianstad. Tel.: 044-76967 Laurentius Petri Sällskapet bildades 1941. Dess årsbok har till uppgift att presen- tera, diskutera och föra ut forskning och utvecklingsarbete -

Levande Svensk Poesi

LEVANDE SVENSK POESI Dikter från 600 år / urval av Björn Håkanson NATUR OCH KULTUR INNEHÅLL FÖRORD ZI BALLADER OCH ANDRA DIKTER AV OKÄNT URSPRUNG 23 Harpans kraft 23 • Herr Olof och älvorna 25 • Jungfrun i hindhamn 27 • Tores döttrar i Vänge 28 • Sorgens makt 31 • Bonden och hans hustru 32 • Gamle man 33 • Den bakvända visan 34 • Duvan och vallmon 35 TROLLFORMLER 35 GÅTOR 38 BISKOP THOMAS D. 1443 Frihetsvisan 39 LARS WIVALLIUS 1605-1669 Klagevisa över denna torra och kalla vår 40 GEORG STIERNHIELM 1598-1672 Kling-dikt 45 • Ur Herkules 45 • Ur Freds-a vi: Utplundrade bönder 50 • Ur Parnassus Triumphans: En filosof • Två soldater • Sirenens sång 51 • Oppå en spindel, som virkar sitt dvärgsnät 52 • På månan, som en hund skäller oppå 52 • Ur Hälsepris 52 SKOGEKÄR BERGBO (PSEUDONYM, I6OO-TALET) Sonetter ur Venerid: no 2 Dig vill jag älska än 53 • no 12 Se nu är natten lång 54 • no 17 Var finner jag en skog 54 • no 55 Vad ursprung hava dock 55 • no 56 O Sömn, de sorgses tröst 55 • no 92 Hon kom all klädd i vitt 56 • no 94 Förr- än jag skulle dig 56 LASSE JOHANSSON (LUCIDOR) 1638-1674 Skulle jag sörja, då vore jag tokot 57 • Sviklige världens oundviklige Öd'-dödlig- hets Sorg-Tröstande Liksång 58-0 syndig man! 60 SAMUEL COLUMBUS 1642-1679 Lustwin dansar en gavott med de fem sinnena 63 • Gravskrift över Lucidor 64 ISRAEL KOLMODIN 1643-1709 Den blomstertid nu kommer 64 HAQUIN SPEGEL 1645-1714 Emblemdikt 65 [5] LEVANDE SVENSK POESI SOPHIA ELISABETH BRENNER 1659-1730 Klagan och tröst emot den omilda lyckan 66 GUNNO EURELIUS DAHLSTIERNA 1661-1709 -

Fredrika Bremer: Famillen H***

Fredrika Bremer FAMILLEN H*** SVENSKA FÖRFATTARE NY SERIE Fredrika Bremer FAMILLEN H*** Utgiven med inledning och kommentarer av Åsa Arping SVS SVENSKA VITTERHETSSAMFUNDET STOCKHOLM 2000 Utgiven med bidrag av Stiftelsen Riksbankens Jubileumsfond Abstract Fredrika Bremer, Famillen H***. Utgiven med inledning och kommentarer av Åsa Arping. (Fredrika Bremer, The H-Family. Edited with introduction and commentary by Åsa Arping, Department of Comparative Literature, Göteborg University, Box 200, SE-405 30 Göteborg, Sweden.) Skrifter utgivna av Svenska Vitterhetssamfundet. Svenska författare. Ny serie, XXVI+242 pp., Stockholm. ISBN 91-7230-094-9 Famillen H*** (The H-Family) appeared in the second and third part of Teck- ningar utur hvardagslifvet (Sketches from Every-day Life), published anon- ymously in 1830–31. This début was an immediate success and the writer’s identity was soon revealed. Here Fredrika Bremer (1801–1865) presented the reader to a literary landscape previously unknown in Sweden. Ordinary con- temporary milieus and characters are unerringly described through a quick prose easily varying from elevated to quiet and humouristic. Alongside of and often in opposition to romanesque conventions this book offered a new kind of realistic account. For the first time Famillen H*** now appeares in a critical edition. The text, based on the first edition, is preceded by an introduction presenting the creation and reception of the novel, and is followed by a commentary. © Svenska Vitterhetssamfundet ISBN 91-7230-094-9 Svenska Vitterhetssamfundet c/o Svenska Akademiens Nobelbibliotek Box 2118, SE-103 13 Stockholm http://svenska.gu.se/vittsam.html Printed in Sweden by Bloms i Lund Tryckeri AB Lund 2000 Inledning Det är besatt, besatt, besatt! Jag tror att någon välmenande hexa har sagt hokus pokus öfver mig och min lilla bok. -

HL:N Vapaasti Tykitettävät Laulut V. 2011

HL:n vapaasti tykitettävät laulut v. 2011 (olettaen, että tuntemattomat ovat oikeasti tuntemattomia… Jos joku tietää paremmin, ilmoittakoot: hsm(at)hsmry.fi) 1 Pyhä, pyhä, pyhä san. Reginald Heber (k. 1826) suom. Mikael Nyberg (k. 1940) 4 Jumala ompi linnamme san. Martti Luther (k. 1546) suom. Jacobus Petri Finno (Jaakko Suomalainen) (k. 1588) 5 Herralle kiitos ainiaan san. Thomas Ken (k. 1711) suom. tuntematon 7 Armo Jumalan san, Jens Nicolai Ludvig Schjörring (k. 1900) suom. tuntematon 9 Laula Herran rakkaudesta san. Samuel Trevor Francis (k. 19259 suom. tuntematon 10 Laula minulle uudestaan san. Philip Paul Bliss (k. 1876) suom. tuntematon 11 Uskomme Jumalaan san. Saksalainen suom. Julius Leopold Fredrik Krohn (k. 1888) 12 Min lupaapi Herra san. S. C. Kirk (k. 1900-luvulla) suom. tuntematon 13 Suuri Jumala, sinussa san. Josepha Gulseth (k. ?) suom. tuntematon 14 Oi Herra suuri san. Carl Gustaf Boberg (k. 1940) suom. tuntematon 15 Oi Jeesus, sanas ääreen san. Anna Helena Ölander (k. 1939) suom. Tekla Renfors, os. Mömmö (k. 1912) 17 Minä tyydyn Jumalaan san. Benjamin Schmolock (k. 1700-luvulla) suom. tuntematon 18 On Herra suuri san. Anton Valtavuo (k. 1931) 22 Suuri Luoja, kiittäen san. Ignaz Franz (k. 1790) suom. Aina G. Johansson (k. 1932) 24 Tää sana varma san. Joël Blomqvist (k. 1930) suom. tuntematon 26 En etsi valtaa loistoa san. Sakari Topelius (k. 1898) suom. tuntematon 28 Joulu, joulu tullut on san. Olli Vuorinen (k. 1917) 29 Enkeli taivaan san. Martti Luther suom. Hemminki Maskulainen, uud. Julius Krohn (k. 1888) 31 Kun joulu valkeneepi san. Abel Burckhart (k. 1800-luvulla) suom. tuntematon 32 Juhla on rauhainen san. -

Luther Brassensemble

Luther Brassensemble Luther Brassensemble, är en professionell ensemble med handplockade musiker från bland annat GöteborgsOperan, Göteborg Wind Orchestra och Bohuslän BigBand. Tillsammans spelar vi psalmer och koralfantasier i klassisk possaunenchor (trombonkör) och brassensemble. Ensemblen utgörs av fyra trumpeter, ett valthorn, fyra tromboner, en tuba och en slagverkare, vilket utgör den perfekta sammansättningen musiker för att fylla kyrkorummet med underbara klanger. Firandet av Martin Luther och det kommande reformationsåret närmar sig med stormsteg, vad är väl bättre än att fra denna höjdpunk med ljuvlig brassmusik? Cirka 500 år efter reformationstiden har vi i Luther Brassensemble satt ihop ett konsertprogram med välkända, folkkära svenska och tyska psalmer från 1500-1600-talet i både traditionell och ny fattning. Vi erbjuder upplyftande brassmusik på högsta nivå. I konserten fnns det möjlighet för textläsning och församlingssång (eventuellt andakt). Vi har hämtat inspiration från våra tyska kollegor i Genesis Brass, och lägger därför med en ljudfl från deras inspelning av psalm #2 – Herren, vår Gud, är en konung (Lobe den Herren, den machtigen Konig). Genesis Brass fnns även att lyssna på via Spotify. Vi är tillgängliga under perioden 1 mars till 9 april, 2 maj till 4 juni och är även tillgängliga för bokningar under hösten. Då vi kommer att turnera med denna produktion behövs ett samarbete gällande konsertdatum från Er och oss. För praktisk information och programförslag se följande sidor. Vi ser mycket fram emot att höra från er. Med Vänliga Hälsningar Bjørn Bjerknæs-Jacobsen Ensembleledare Programförslag 1. Wach auf, mein Herz, und singe! Text: Paul Gerhards (1647/1653) Musik: Nikolaus Selnecker (1587) (Koralmelodi Nun lasst uns Gott dem Herren) 2. -

Fifth Sunday After Pentecost

Fifth Sunday after Pentecost Messiah Lutheran Church (440) 331-2405 June 27, 2021 MessiahChurchFairview.org To our Guests: Welcome! Worship Patterns in Pandemic Days God be praised for every person here this morning and for all who are with us in spirit as they watch and pray at home. God strengthen us all through his word and promise in our Lord Jesus Christ. The coronavirus infection continues to threaten people who have not been vaccinated. In our determined care for each other, please follow these rules: On entering— • Masks are required. Please be sure to wear one. • Sit only in pews marked with a bow. • Keep the spacing rod between you and your family and the person or family at the other end. • Greet each other from a distance. During the service— • You may sing, but with masks in place. • When we share the Peace, do not hug or shake hands. Instead wave or bow to the people around you. • Offering plates will not passed. If you missed the basket on your way in, place it there when you leave. During communion— • Keep a safe distance from the person in front of you as you approach. • Hold out your cupped hands for the host. The pastor will not place this in your mouth or extended fingers. • For the wine, take a plastic cup from the top of the stand, and hold it steady as the pastor fills it. Deposit the cup in the receptacle as you return to your place. As you leave— • Unless you need the elevator, exit through front doors only. -

Mina Psalmböcker Och Annat Psalmrelaterat

Mina psalmböcker och annat psalmrelaterat Uppdaterad den 17 juni 2018 www.psalmbok.se Böcker jag inte har (eller glömt stryka här) ID Kategori Författare/Utgiven av Titel Tryckår Ur Wessmans register. Ej insorterade utgåvor nedan 1687 (dansk), 1690, 1693, Barnabok, hans kongl. höghet kronprinsen i Gustaf Murray och Johan Wellander, underdånighet tilägnad af samfundet Pro fide 1 Har inte Sthlm. Psalmernas väg, nr 193 et christianismo 1780 Som, Efter Hans Kongl Maj:ts Nådigsta Befallning, bör utgifwas (har del 2, 178 - 485 n:r). Sthlm, Lorens Ludvig Grefing. Kallas Celsiska 1765 års - Av Then Swenska Prof-Psalmbok 2 Har inte provpsalmboken Första Samlingen (nr 1-177) 1765 Joachim von Düben d.ä. Stockholm. Tryckt hos Joh. L. Horn. Psalmernas Uthwalde andelige sånger, af tyska språket på 3 Har inte väg, nr 200 swensko tolckade 1725 Jacob Arrhenius. Upsala. Psalmernas 4 Har inte väg, nr 4, 138 Jacobi Arrhenii Psalme-prof 1689 Haquin Spegel. Västerås. Psalmernas En christens gyllende Clenodium eller Siäle- 5 Har inte väg, nr 186 skatt 1688 Ericus Laurentii Norenius. Wästeråhs (förlorad). Psalmernas väg, nr 138, Gudfruchtigheetz öfning, uthi christelig och 6 Har inte 144 upbyggelige sånger om Jesu Christi lijdande 1675 Samuel Columbus & Gustaf Düben d.ä. (jmfr ej beslagen 1694!) Sthlm Johan Georg Eberdt. Psalmernas väg, Odæ sveticæ. Thet är, någre 7 Har inte nr 43. Digital. (finns repr i Syréens) werldsbetrachtelser, sång-wijs författade 1674 8 Har inte Psalmernas väg, nr 104 Tree sköna andelighe wijsor 1642 9 Har inte Basilius Förtsch. Psalmernas väg, nr 42 En andeligh watukälla 1641 Sigfrid Aron Forsius. Psalmernas väg, 10 Har inte nr 147 (ej belagd) En liten psalmbok 1608 11 Har digital Psalmernas väg, nr 71. -

Nils Landgren

Nils Landgren Christmas With My Friends VI ACT 9872-2 German release date: 26. October 2018 Christmas without the songs – it's unthinkable. And And mentioning Ida Sand, she is not only the pianist yet how can one be open to different musical styles and for this little Christmas ensemble, she also brings her also strike a good balance between them? How can all the bitter-sweet voice to it. For many years she has been one of right moods for the festive season be captured? Should it the outstanding white soul voices in Europe, and is the be classical or soulful, gospel or pop, blues or jazz? perfect singer for the bluesy "Merry Christmas Baby", and The result can often be just one style of singing from one for Dave Grusin's soul song "Who Comes This Night". person – but that’s not the case with Nils Landgren's "Christmas With My Friends". A sequence which would Jessica Pilnäs has a clear and bright timbre, hers is a normally have had to be patched together from a wide disarmingly light voice, and she has a fine understanding of range of interpreters is all there, and from just the one how jazz should flow. She caused a sensation in 2012 with source. Alongside the Swedish trombonist/singer himself, a Peggy Lee tribute. She has exactly the right voice and there are four vocalists, Jeanette Köhn, Ida Sand, Jessica attitude for standards like Frank Loesser's "What Are You Pilnäs and Sharon Dyall, and their fundamentally different Doing New Year's Eve?" and for her own composition voices allow them to combine many musical genres.