Determining Strategies for Success in the Opera Industry: a Case Study from Gauteng

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XVIII, Number 1 April 2003 A PILGRIMAGE TO IOWA As I sat in the United Airways terminal of O’Hare International Airport, waiting for the recently bankrupt carrier to locate and then install an electric starter for the no. 2 engine, my mind kept returning to David Lodge’s description of the modern academic conference. In Small World (required airport reading for any twenty-first century academic), Lodge writes: “The modern conference resembles the pilgrimage of medieval Christendom in that it allows the participants to indulge themselves in all the pleasures and diversions of travel while appearing to be austerely bent on self-improvement.” He continues by listing the “penitential exercises” which normally accompany the enterprise, though, oddly enough, he omits airport delays. To be sure, the companionship in the terminal (which included nearly a dozen conferees) was anything but penitential, still, I could not help wondering if the delay was prophecy or merely a glitch. The Maryland Handel Festival was a tough act to follow and I, and perhaps others, were apprehensive about whether Handel in Iowa would live up to the high standards set by its august predecessor. In one way the comparison is inappropriate. By the time I started attending the Maryland conference (in the early ‘90’s), it was a first-rate operation, a Cadillac among festivals. Comparing a one-year event with a two-decade institution is unfair, though I am sure in the minds of many it was inevitable. Fortunately, I feel that the experience in Iowa compared very favorably with what many of us had grown accustomed Frontispiece from William Coxe, Anecdotes fo George Frederick Handel and John Christopher Smith to in Maryland. -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XXVII, Number 2 Summer 2012 FROM THE PRESIDENT’S DESK SUMMER 2012 I would like to thank all the members of the Society who have paid their membership dues for 2012, and especially those who paid to be members of the Georg-Friedrich-Händel Gesellschaft and/or friends of The Handel Institute before the beginning of June, as requested by the Secretary/Treasurer. For those of you who have not yet renewed your memberships, may I urge you to do so. Each year the end of spring brings with it the Handel Festivals in Halle and Göttingen, the latter now regularly scheduled around the moveable date of Pentecost, which is a three-day holiday in Germany. Elsewhere in this issue of the Newsletter you will find my necessarily selective Report from Halle. While there I heard excellent reports on the staging of Amadigi at Göttingen. Perhaps other members of the AHS would be willing to provide reports on the performances at Göttingen, and also those at Halle that I was unable to attend. If so, I am sure that the Newsletter Angelica Kauffmann, British, born in Switzerland, 1741-1807 Portrait of Sarah Editor would be happy to receive them. Harrop (Mrs. Bates) as a Muse ca. 1780-81 Oil on canvas 142 x 121 cm. (55 7/8 x 47 5/8 in.) Princeton University Art Museum. Museum purchase, Surdna Fund The opening of the festival in Halle coincided and Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund 2010-11 photo: Bruce M. White with the news of the death of the soprano Judith Nelson, who was a personal friend to many of us. -

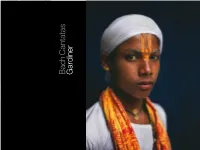

B Ach C Antatas G Ardiner

Johann Sebastian Bach 1685-1750 Cantatas Vol 3: Tewkesbury/Mühlhausen SDG141 COVER SDG141 CD 1 76:03 For the Fourth Sunday after Trinity Ein ungefärbt Gemüte BWV 24 Barmherziges Herze der ewigen Liebe BWV 185 Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ BWV 177 Magdalena Kozˇená soprano, Nathalie Stutzmann alto Paul Agnew tenor, Nicolas Teste bass For the Fifth Sunday after Trinity Gott ist mein König BWV 71 C CD 2 62:12 Aus der Tiefen rufe ich, Herr, zu dir BWV 131 M Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten BWV 93 Y Siehe, ich will viel Fischer aussenden BWV 88 K Joanne Lunn soprano, William Towers alto Kobie van Rensburg tenor, Peter Harvey bass The Monteverdi Choir The English Baroque Soloists John Eliot Gardiner Live recordings from the Bach Cantata Pilgrimage Tewkesbury Abbey, 16 July 2000 Blasiuskirche, Mühlhausen, 23 July 2000 Soli Deo Gloria Volume 3 SDG 141 P 2008 Monteverdi Productions Ltd C 2008 Monteverdi Productions Ltd www.solideogloria.co.uk Edition by Reinhold Kubik, Breitkopf & Härtel Manufactured in Italy LC13772 8 43183 01412 5 SDG 141 Bach Cantatas Gardiner 3 Bach Cantatas Gardiner CD 1 76:03 For the Fourth Sunday after Trinity 1-6 17:01 Ein ungefärbt Gemüte BWV 24 7-12 14:41 Barmherziges Herze der ewigen Liebe BWV 185 13-17 25:06 Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ BWV 177 BWV 24, 185, 177 Magdalena Kozˇená soprano, Nathalie Stutzmann alto The Monteverdi Choir The English Double Bass Harpsichord Baroque Soloists Valerie Botwright Howard Moody Sopranos Paul Agnew tenor, Nicolas Teste bass Cecelia Bruggemeyer Lucinda Houghton First Violins -

MONTEVERDI's OPERA HEROES the Vocal Writing for Orpheus And

MONTEVERDI’S OPERA HEROES The Vocal Writing for Orpheus and Ulysses Gustavo Steiner Neves, M.M. Lecture Recital Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS Karl Dent Chair of Committee Quinn Patrick Ankrum, D.M.A. John S. Hollins, D.M.A. Mark Sheridan, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School May, 2017 © 2017 Gustavo Steiner Neves Texas Tech University, Gustavo Steiner Neves, May 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES iv LIST OF TABLES iv CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 1 Thesis Statement 3 Methodology 3 CHAPTER II: THE SECOND PRACTICE AND MONTEVERDI’S OPERAS 5 Mantua and La Favola d’Orfeo 7 Venice and Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria 13 Connections Between Monteverdi’s Genres 17 CHAPTER III: THE VOICES OF ORPHEUS AND ULYSSES 21 The Singers of the Early Seventeenth Century 21 Pitch Considerations 27 Monteverdi in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries 30 Historical Recordings and Performances 32 Voice Casting Considerations 35 CHAPTER IV: THE VOCAL WRITING FOR ORPHEUS AND ULYSSES 37 The Mistress of the Harmony 39 Tempo 45 Recitatives 47 Arias 50 Ornaments and Agility 51 Range and Tessitura 56 CHAPTER V: CONCLUSIONS 60 BIBLIOGRAPHY 63 ii Texas Tech University, Gustavo Steiner Neves, May 2017 ABSTRACT The operas of Monteverdi and his contemporaries helped shape music history. Of his three surviving operas, two of them have heroes assigned to the tenor voice in the title roles: L’Orfeo and Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria. -

R. Larry Todd, Discovering Music Audio Credits Part I Chapter 3

R. Larry Todd, Discovering Music Audio Credits Part I Chapter 3 Listening Map 1: “The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, Op. 34” Composed By: Benjamin Britten Performed By: London Symphony Orchestra, Steuart Bedford Chapter 6 Listening Map 2: “The Stars and Stripes Forever” Composed By: John Philip Sousa Performed By: Royal Artillery Band, Keith Brion Part II Chapter 8 Listening Map 3: “Viderunt Omnes” Composed By: Anonymous Performed By: CantArte Regensburg, Hubert Velten Chapter 9 Listening Map 4 “O viridissima virga” Composed By: Hildegard Von Bingen Performed By: Oxford Camerata, Jeremy Summerly Chapter 10 Listening Map 5 “Viderunt Omnes” Composed By: Leonin Performed By: Tonus Peregrinus, Antony Pitts Chapter 11 Additional Audio, Page 81 “A chantar m'er de so qu'ieu non volria” Composed By: La Comtesse de Die Performed By: Mara Kiek, Sinfonye Chapter 12 Listening Map 6 “Songs from Le Voir Dit: Rondeau 18: Puis qu’en oubli” Composed By: Guillaume Machaut Performed By: Oxford Camerata, Jeremy Summerly Listening Map I.1 “Jula Jekere” Performed By: Foday Musa Suso Recorded By: Verna Gillis Part III Chapter 14 Listening Map 7 “Se la face ay pale” Composed By: Guillaume Dufay Performed By: The Binchois Consort, Andrew Kirkman Chapter 15 Listening Map 8 “Ave Maria” Composed By: Josquin des Prez Performed By: Oxford Camerata, Jeremy Summerly Chapter 16 Listening Map 9 “Missa Papae Marcelli, “Pope Marcellus Mass”: Kyrie” Composed By: Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina Performed By: Oxford Camerata, Jeremy Summerly Chapter 17 Additional Audio, Page 114 “Moro, lasso, al mio duolo” Composed By: Carlo Gesualdo Performed By: Musicae Delitiae, Marco Longhini Listening Map 10 “As Vesta was, from Latmos hill descending” Composed By: Thomas Weelkes Performed By: Sarum Consort, Andrew Mackay Chapter 18 Listening Map 11 “Pavana and Galiarda in F Major, No. -

Rodelinda Regina De’Longobardi

George Frideric Handel Rodelinda Regina de’Longobardi CONDUCTOR Opera in three acts Harry Bicket Libretto by Nicola Francesco Haym, adapted from PRODUCTION Antonio Salvi’s work of the same name Stephen Wadsworth Saturday, December 3, 2011, 12:30–4:35 pm SET DESIGNER Thomas Lynch COSTUME DESIGNER Martin Pakledinaz LIGHTING DESIGNER The production of Rodelinda was made possible Peter Kaczorowski by a generous gift of John Van Meter. Additional funding was received from Mercedes and Sid Bass, and the Hermione Foundation. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR Fabio Luisi 2011–12 Season The 20th Metropolitan Opera performance of George Frideric Handel’s Rodelinda Regina de’Longobardi This performance conductor is being Harry Bicket broadcast live over The cast in order of appearance Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Rodelinda, Queen of Milan, wife of Bertarido Opera Renée Fleming International Radio Network, Grimoaldo, usurper of Milan, betrothed to Eduige sponsored by Joseph Kaiser Toll Brothers, America’s luxury Garibaldo, counselor to Grimoaldo homebuilder®, Shenyang * with generous long-term Eduige, Bertarido’s sister, bethrothed to Grimoaldo support from Stephanie Blythe * The Annenberg Bertarido, King of Milan, believed to be dead Foundation, the Andreas Scholl Vincent A. Stabile Endowment for Unulfo, counselor to Grimoaldo, secretly loyal Broadcast Media, to Bertarido and contributions Iestyn Davies from listeners worldwide. Flavio, son of Rodelinda and Bertarido Moritz Linn This performance is also being continuo: broadcast live on Harry Bicket, harpsichord recitative Metropolitan Opera Bradley Brookshire, harpsichord ripieno Radio on SiriusXM David Heiss, cello , theorbo and baroque guitar channel 74. Daniel Swenberg Saturday, December 3, 2011, 12:30–4:35 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

Master Oper & Musiktheater 2021

BEWERBUNG | ADMISSIONS DEPARTMENT Zusätzlich wird die Ausbildung regelmäßig durch eine Reihe von re- OPER UND MUSIKTHEATER nommierten Gastdozentinnen und -dozenten ergänzt. Schwerpunkte Voraussetzungen für die Aufnahme in den Masterstudiengang „Oper sind hier z. B. das „Vorsing-Training“ (zuletzt u. a. mit Evamaria Wieser und Musiktheater“ sind ein abgeschlossenes Bachelorstudium Gesang DEPARTMENT OF – YSP Salzburger Festspiele; Esther Schollum – Artists Management oder ein gleichwertiger Studienabschluss und das Bestehen eines Aus- OPERA AND MUSIC THEATRE Wien; Sebastian Schwarz – Glyndebourne Festival, Intendant Teatro wahlverfahrens über drei Runden. Für das Vorsingen sollen sechs Ari- Regio Turino; Aviel Cahn – Intendant Theater Genf) sowie die stilistische en bzw. Opernszenen unterschiedlicher Stilepochen in verschiedenen Departmentleitung | Chair Weiterbildung und interpretatorische Vertiefung in Form von Meister- Master Sprachen vorbereitet werden. Davon zwei szenisch, mindestens eine in Univ.Prof. Gernot Sahler kursen (zuletzt u. a. Dame Felicity Lott, Andrew Watts und Kobie van deutscher und eine in italienischer Sprache sowie eine Arie mit Rezita- Rensburg). Oper & Musiktheater tiv. Das Programm ist auswendig vorzutragen. Musikalische Leitung Szenische Leitung Music director Stage director Bitte beachten Sie, dass Sie sich an der Universität Mozarteum grund- Univ.Prof. Kai Röhrig Univ.Prof. Alexander von Pfeil PHILOSOPHY sätzlich zur Aufnahmeprüfung für mehrere Masterstudiengänge (z.B. Univ.Prof. Gernot Sahler Master Lied und Oratorium) anmelden können. Today‘s music theatre business makes many demands on young sing- Lehrende des Departments für Gesang | Voice Faculty ing actresses and actors. With its high practical relevance in the con- Prerequisites for admission to the Master’s program “Opera and Mu- Univ.Prof. Juliane Banse text of professional opera productions, the specialized training in the sic Theatre” are a completed Bachelor’s degree or its equivalent in Univ.Prof. -

August/September 2020

August/September 2020 Krefeld Mönchengladbach August OMOM August OMOM GROSSE BÜHNE ANDERE SPIELORTE GROSSE BÜHNE ANDERE SPIELORTE Seidenweberhaus Schloss Rheydt 25 1. Sinfoniekonzert 22 Amor y Zarzuela / Mit Werken von Wolfgang Amadeus Spanisch-mediterrane Di Mozart und Ludwig van Beethoven Sa Klassiknacht 20 Uhr | Konzertabo · – ohne Pause 20 – ca. 21.10 Uhr · Eintritt: 26,– / ermäßigt:* 16,– Eintritt: 31,50 * Karten unter: www.voilakonzerte.de Seidenweberhaus 28 1. Sinfoniekonzert Kleine Operngala mit Mit Werken von Wolfgang Amadeus 23 großen Stimmen Fr Mozart und Ludwig van Beethoven Mitglieder des Ensembles und des 20 Uhr | Konzertabo · – ohne Pause So Opernstudio Niederrhein singen Eintritt: 26,– / ermäßigt:* 16,– Duette und Arien von Giuseppe Verdi, Gaetano Donizetti, Georges Bizet u.a. Kleine Operngala mit Seidenweberhaus 18 – 19.30 Uhr – ohne Pause · 30 großen Stimmen 1. Sinfoniekonzert Eintritt: 26,– / ermäßigt: 16,*– Mitglieder des Ensembles und des Mit Werken von Wolfgang Amadeus So Opernstudio Niederrhein singen Mozart und Ludwig van Beethoven Konzertsaal Duette und Arien von Giuseppe Verdi, 20 Uhr | Konzertabo · – ohne Pause 26 1. Sinfoniekonzert Gaetano Donizetti, Georges Bizet u.a. Eintritt: 26,– / ermäßigt:* 16,– Mit Werken von Wolfgang Amadeus 18 – 19.30 Uhr – ohne Pause · Mi Mozart und Ludwig van Beethoven Eintritt: 26,– / ermäßigt: 16,*– 20 Uhr | Konzertabo · – ohne Pause Eintritt: 26,– / ermäßigt:* 16,– September OMOM Konzertsaal Abo-Cocktail 2020/21 27 1. Sinfoniekonzert 6 Spielplanvorstellung Mit Werken von Wolfgang Amadeus aufgrund der Platzbeschränkungen Do Mozart und Ludwig van Beethoven So nur für Abonnenten 20 Uhr | Konzertabo · – ohne Pause 11 Uhr Eintritt: 26,– / ermäßigt:* 16,– Live-Stream auf www.theater-kr-mg.de 29 PREMIERE PREMIERE Goodbye to Berlin 12 Carmen Szenische Lesung nach Oper von Georges Bizet Sa Kurzgeschichten Sa Konzertante Aufführung von Chr. -

Die Zauberflöte

Die Zauberflöte Oper von Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Libretto von Emanuel Schikaneder Theaterpädagogische MATERIALMAPPE 13/14 1. Einleitung Liebe Pädagoginnen und Pädagoginnen, endlich läuft meine persönliche Lieblingsoper bei uns im Großen Haus! Mit den nachgesungenen Arien der ZAUBERFLÖTE hab ich schon als Sechsjährige meine Fa- milie in den Wahnsinn getrieben. Keine Note saß, aber in meinem Kopf klang alles richtig. Und nicht nur ich habe das als Dauerschleife gesungen – eine Schallplatte mit der berühmten Arie der Königin der Nacht Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen wurde vor über 30 Jahren von der NASA an Bord zweier Raumsonden ins All geschickt, um damit vielleicht eines Tages außerirdische Opernfreunde damit zu beglücken…! DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE beinhaltet die bekanntesten Gassenhauer der klassischen Musik. Bekannte Melodien, vertraute Themen, lustige Identifikationsfiguren, eine spannen- de Geschichte, Bösewichte, Rätsel, Liebe – und ein Happy End. DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE bietet das alles. Nicht nur daher freuen wir uns sehr, dass die Inszenierung im Thea- terJugendRing zu sehen ist, denn es gibt fast keine bessere Oper zum Einstieg ins klassische Musiktheater. Wir bieten Ihnen mit dieser kleinen Stoffsammlung natürlich nur einen Bruchteil dessen, was man zur ZAUBERFLÖTE mit SchülerIhnnen arbeiten kann. Vielleicht hilft Ihnen unsere Materialmappe weiter, vielleicht kommen Sie selber auf Ideen, die der Schulgruppe die Sie begleiten angemessener sind. In jedem Fall freuen wir uns darauf, Sie und Ihre SchülerInnen im Großen Haus ver- zaubern zu können – mit großartigen Sängerinnen und Sängern, viel Mozart, viel Fantasy und viel Herzblut! Mit besten Grüßen aus den heiligen Hallen,, Anne Verena Freybott & Angelika Schlaghecken Junges Theater Münster Neubrückenstraße 63 48143 Münster [email protected] (0251)-5909-211 [email protected] (0251)-5909-158 2 2. -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XIX, Number 1 April 2004 THE THOMAS BAKER COLLECTION In 1985 the Music Library of The University of Western Ontario acquired the bulk of the music collection of Thomas Baker (c.1708-1775) of Farnham, Surrey from the English antiquarian dealer Richard Macnutt with Burnett & Simeone. Earlier that same year what is presumed to have been the complete collection, then on deposit at the Hampshire Record Office in Winchester, was described by Richard Andrewes of Cambridge University Library in a "Catalogue of music in the Thomas Baker Collection." It contained 85 eighteenth-century printed titles (some bound together) and 10 "miscellaneous manuscripts." Macnutt described the portion of the collection he acquired in his catalogue The Music Collection of an Eighteenth Century Gentleman (Tunbridge Wells, 1985). Other buyers, including the British Library, acquired 11 of the printed titles and 4 of the manuscripts. Thomas Baker was a country gentleman and his library, which was "representative of the educated musical amateur’s tastes, include[d] works ranging from short keyboard pieces to opera" (Macnutt, i). Whether he was related to the Rev. Thomas Baker (1685-1745) who was for many years a member of the choirs of the Chapel Royal, St. Paul’s Cathedral, and Westminster Abbey, is not clear. Christoph Dumaux as Tamerlano – Spoleto Festival USA 2003 However, his collection did contain several manuscripts of Anglican Church music. TAMERLANO AT SPOLETO The portion of the Thomas Baker Collection now at The University of Western Ontario, consisting of 83 titles, is FESTIVAL USA 2003 admirably described on the Music Library’s website Composer Gian Carlo Menotti founded the Festival dei (http://www.lib.uwo.ca/music/baker.html) by Lisa Rae Due Mondi in 1958, locating it in the Umbrian hilltown of Philpott, Music Reference Librarian. -

THE CAPE TOWN BAROQUE FESTIVAL 21 - 24 September 2017

presents THE CAPE TOWN BAROQUE FESTIVAL 21 - 24 September 2017 For the Cape Town Baroque Festival: Artistic director: Erik Dippenaar | Finance director: Alrich Rooy Publicity: Wayne Muller | Logistics coordinator: Louise Howlett FESTIVAL PROGRAMME BAROQUE OPERA GALA Thursday 21 September, 20.00 With Lynelle Kenned, Elsabé Richter, Sandile Mabaso and Bongani Khubeka Pre-concert talk by Anna Stoddard ‘Baroque Divas’ St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Green Point CHAMBER MUSIC FROM THE BAROQUE Friday 22 September, 20.00 With Baroque2000 St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Green Point FROM BACH TO BACH Saturday 23 September, 13.00 With John Reid Coulter (fortepiano) St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Green Point HISTORICAL WALKING TOUR Saturday 23 September, 14.30 Walking tour of historic city centre buildings With heritage architect John Rennie St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Green Point VOICES OF VOX Saturday 23 September, 20.00 With VOX Cape Town Choir St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Green Point THE BACHS – A FAMILY AFFAIR Sunday 24 September, 11.30 With the Cape Consort, directed by Hans Huyssen Lutheran Church, Strand Street SING FOR YOUR SUPPER GOES BAROQUE Sunday 24 September, 13.00 With Monika Voysey, Nick de Jager and Erik Dippenaar Welgemeend, 2 Welgemeend Street, Gardens CAMERATA TINTA BAROCCA, founded in Cape Town by violinist Quentin Crida in July 2004, is the leading South African baroque ensemble playing on period instruments. Its name is derived from the musicians’ passion for baroque music and red wine. The members include some of Cape Town’s finest musicians who embrace a historically informed performance practice approach. CTB’s concerts have been broadcast on Fine Music Radio and have received critical acclaim in the Cape Times and Die Burger. -

SWR2 Musikstunde

1 SWR2 MANUSKRIPT SWR2 Musikstunde „Claudio Monteverdi! Zum 450. Geburtstag!“ „Il Divino Claudio!“ Mit Sabine Weber Sendung: 17. Mai 2017 Redaktion: Dr. Bettina Winkler Produktion: SWR 2017 Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Service: SWR2 Musikstunde können Sie auch als Live-Stream hören im SWR2 Webradio unter www.swr2.de Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2-Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de 2 SWR2 Musikstunde mit Sabine Weber 15. Mai – 19. Mai 2017 MONTEVERDI 3 Il Divino Claudio! Il Divino Claudio! Heute über den Opernvisionär Claudio Monteverdi! Ich bin Sabine Weber. Herzlich Willkommen! Titelmusik kurz (10.sec) MODERATION Stechend schwarze Augen blicken herausfordernd aus einem kantigen Gesicht mit Gesichtsfurchen, die von einem Bart nur wenig gemildert werden. Relativ spät ist das einzige gesicherte Portrait von Claudio Monteverdi entstanden (das Tiroler Landesmuseum in Innsbruck, wo es hängt, datiert es auf 1630). Und zeigt ein erschreckend gealtertes Gesicht. Zweifellos auch von alchimistischen Selbstversuchen gezeichnet. Zu erkennen sind aber vor allem die ausgemergelten Züge eines ruhelos Suchenden, der sich bis zur Selbstaufgabe kasteit hat, wenn es um seine Obsession ging: Die Wahrhaftigkeit des Ausdrucks hinter dem Wort in der Musik! Der Affekt, der zu Tränen rührt! Und von diesem Affekt lassen sich zum Auftakt heute … Nicht-Barock-Spezialisten anstecken..