THE SAKAS Part-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

BS-10 Text Part1.Cdr

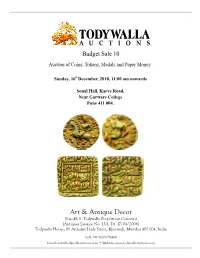

Budget Sale 10 Auction of Coins, Tokens, Medals and Paper Money Sunday, 16th December, 2018, 11:00 am onwards Sonal Hall, Karve Road, Near Garware College Pune 411 004. Art & Antique Decor (Farokh S. Todywalla Proprietary Concern) [Antiques Licence No. 13A, Dt. 17/04/2006] Todywalla House, 80 Ardeshir Dady Street, Khetwadi, Mumbai 400 004. India Cell: +91-9820 054408 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.todywallaauctions.com Date of Sale: Sunday, 16th December, 2018, 11:00 am onwards Public View: Friday & Saturday 14th & 15th December, 11:00 am - 4:00 pm - At the venue By Appointment: 7th December to 13th December, 3 pm to 6 pm at Art & Antique Decor Todywalla House, 80 Ardeshir Dady Street, Khetwadi, Mumbai 400 004. India. Phone: +91-9820054408 Order of Sale: Ancient Coins................................................................... Lots 001 - 053 Hindu Coins of Medieval India ....................................... Lots 054 - 065 Sultanates ........................................................................ Lots 066 - 074 Mughals ........................................................................... Lots 075 - 157 Independent Kingdoms ................................................... Lots 158 - 168 Princely States ................................................................. Lots 169 - 189 Indo - Portuguese ............................................................ Lots 190 East India Company ......................................................... Lots 191 - 206 British India .................................................................... -

The Heritage of India Series

THE HERITAGE OF INDIA SERIES T The Right Reverend V. S. AZARIAH, t [ of Dornakal. E-J-J j Bishop I J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon.). Already published. The Heart of Buddhism. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A. Asoka. J. M. MACPHAIL, M.A., M.D. Indian Painting. PRINCIPAL PERCY BROWN, Calcutta. Kanarese Literature, 2nd ed. E. P. RICE, B.A. The Samkhya System. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. Psalms of Maratha Saints. NICOL MACNICOL, M.A., D.Litt. A History of Hindi Literature. F. E. KEAY, M.A., D.Litt. The Karma-MImamsa. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. Hymns of the Tamil Saivite Saints. F. KINGSBURY, B.A., and G. E. PHILLIPS, M.A. Rabindranath Tagore. E. J. THOMPSON, B.A., M.C. Hymns from the Rigveda. A. A. MACDONELL, M.A., Ph.D., Hon. LL.D. Gotama Buddha. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A. Subjects proposed and volumes under Preparation. SANSKRIT AND PALI LITERATURE. Anthology of Mahayana Literature. Selections from the Upanishads. Scenes from the Ramayana. Selections from the Mahabharata. THE PHILOSOPHIES. An Introduction to Hindu Philosophy. J. N FARQUHAR and PRINCIPAL JOHN MCKENZIE, Bombay. The Philosophy of the Upanishads. Sankara's Vedanta. A. K. SHARMA, M.A., Patiala. Ramanuja's Vedanta. The Buddhist System. FINE ART AND MUSIC. Indian Architecture. R. L. EWING, B.A., Madras. Indian Sculpture. Insein, Burma. BIOGRAPHIES OF EMINENT INDIANS. Calcutta. V. SLACK, M.A., Tulsi Das. VERNACULAR LITERATURE. and K. T. PAUL, The Kurral. H. A. POPLBY, B.A., Madras, T> A Calcutta M. of the Alvars. -

Note on the Historical Results Deducible from Recent Discoveries in Afghanistan Henry Thoby Prinsep

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1844 Note on the historical results deducible from recent discoveries in Afghanistan Henry Thoby Prinsep Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Prinsep, Henry Thoby Note on the historical results deducible from recent discoveries in Afghanistan. London: W.H. Allen and Co., 1844. vi, 124 page, 17 plates This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE ON THE f HISTORICAL RESULTS, DISCOVERIES IN AFGBANI8TAN. H. T. PRINSEP, ESP. LONDON: WM. H. ALLEN AND CO., 7, LEADENHALL STmET. - 1844. W. I.ICW19 AND SON, PRINTERS, PINCH-LANE, LONDON. PREFACE. THE Public are not unacquainted vith the fact, that dis- coveries of much interest have recently been made ia the regions of Central Asia, which were the seat of Greelr do- minion for some hundred years after their conquest byAlex- ander. These discoveries are principally, but not entirely, nunismatic, and have revealed the names of sovereigns of Greek race, and of their Scythian, and Pa~thiansuccessors, of none of whom is any mention to be found in the extant histories of the East or West. There has also been opencd to the curious, through these coins, a lan- guage, the existence of which was hithcrto unknown, and which must have been the vernacular dialect of some of the regions in which the Grecian colonies were established. -

Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art

Rienjang and Stewart (eds) Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art Edited by Wannaporn Rienjang Peter Stewart Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art Since the beginning of Gandhāran studies in the nineteenth century, chronology has been one of the most significant challenges to the understanding of Gandhāran art. Many other ancient societies, including those of Greece and Rome, have left a wealth of textual sources which have put their fundamental chronological frameworks beyond doubt. In the absence of such sources on a similar scale, even the historical eras cited on inscribed Gandhāran works of art have been hard to place. Few sculptures have such inscriptions and the majority lack any record of find-spot or even general provenance. Those known to have been found at particular sites were sometimes moved and reused in antiquity. Consequently, the provisional dates assigned to extant Gandhāran sculptures have sometimes differed by centuries, while the narrative of artistic development remains doubtful and inconsistent. Building upon the most recent, cross-disciplinary research, debate and excavation, this volume reinforces a new consensus about the chronology of Gandhāra, bringing the history of Gandhāran art into sharper focus than ever. By considering this tradition in its wider context, alongside contemporary Indian art and subsequent developments in Central Asia, the authors also open up fresh questions and problems which a new phase of research will need to address. Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art is the first publication of the Gandhāra Connections project at the University of Oxford’s Classical Art Research Centre, which has been supported by the Bagri Foundation and the Neil Kreitman Foundation. -

History of India

HISTORY OF INDIA VOLUME - 2 History of India Edited by A. V. Williams Jackson, Ph.D., LL.D., Professor of Indo-Iranian Languages in Columbia University Volume 2 – From the Sixth Century B.C. to the Mohammedan Conquest, Including the Invasion of Alexander the Great By: Vincent A. Smith, M.A., M.R.A.S., F.R.N.S. Late of the Indian Civil Service, Author of “Asoka, the Buddhist Emperor of India” 1906 Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar (2018) Preface by the Editor This volume covers the interesting period from the century in which Buddha appeared down to the first centuries after the Mohammedans entered India, or, roughly speaking, from 600 B.C. to 1200 A.D. During this long era India, now Aryanized, was brought into closer contact with the outer world. The invasion of Alexander the Great gave her at least a touch of the West; the spread of Buddhism and the growth of trade created new relations with China and Central Asia; and, toward the close of the period, the great movements which had their origin in Arabia brought her under the influences which affected the East historically after the rise of Islam. In no previous work will the reader find so thorough and so comprehensive a description as Mr. Vincent Smith has given of Alexander’s inroad into India and of his exploits which stirred, even if they did not deeply move, the soul of India; nor has there existed hitherto so full an account of the great rulers, Chandragupta, Asoka, and Harsha, each of whom made famous the age in which he lived. -

The Achaemenid Legacy in the Arsakid Period

Studia Litteraria Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis 2019, special issue, pp. 175–186 Volume in Honour of Professor Anna Krasnowolska doi:10.4467/20843933ST.19.032.10975 www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Litteraria HTTP://ORCID.ORG/0000-0001-6709-752X MAREK JAN OLBRYCHT University of Rzeszów, Poland e-mail: [email protected] The Memory of the Past: the Achaemenid Legacy in the Arsakid Period Abstract The Achaemenid Empire, established by Cyrus the Great, provided a model looked up to by subsequent empires on the territory of Iran and the Middle East, including the empires ruled by Alexander of Macedonia, the Seleukids, and the Arsakids. Achaemenid patterns were eagerly imitated by minor rulers of Western Asia, including Media Atropatene, Armenia, Pontos, Kappadokia and Kommagene. The Arsakids harked back to Achaemenids, but their claims to the Achaemenid descendance were sporadic. Besides, there were no genealogical links between the Arsakids and Achaemenid satraps contrary to the dynastic patterns com- mon in the Hellenistic Middle East. Keywords: Iran, Cyrus the Great, Achaemenids, Arsakids, Achaemenid legacy In this article I shall try to explain why some rulers of the Arsakid period associa- ted their dynasty with the Achaemenids and what the context was of such declara- tions. The focus of this study is on the kings of Parthia from Arsakes I (248–211 B.C.) to Phraates IV (37–3/2 B.C.). The Achaemenids established the world’s first universal empire, spanning ter- ritories on three continents – Asia, Africa, and (temporary) Europe. The power of the Persians was founded by Cyrus the Great (559–530 B.C.), eulogised by the Iranians, Jews, Babylonian priests, and Greeks as well, who managed to make a not very numerous people inhabiting the lands along the Persian Gulf masters of an empire stretching from Afghanistan to the Aegean Sea, giving rise to the largest state of those times. -

Zechariah and the Bible

Bible Study March 1 – Introduction March 8 – The Eight Night Visions March 15 – Zechariah 1:7–13 March 22 – Zechariah 2:1–5 March 29 – Zechariah 9–14 2 3 4 Introduction “When her people fell into enemy hands, there was no one to help her. Her enemies looked at her and laughed at her destruction.” (Lam 1:7) August 28, 587 BC was a dark day in Judah’s history. Nebuchadnezzar, the great Babylonian king, torched Jerusalem’s temple and destroyed the city’s walls. Everything—the monarchy, the priesthood, the storied history in the Promised Land—went up in a puff of smoke. So much seemed closed and controlled by hopeless Babylonian imperial policy. However, to the shock and surprise of everyone, Yahweh raised up his messiah, Cyrus (Is 45:1). Isaiah’s new thing exploded in the desert (Is 43:19). Uprooting and destroying yielded to building and planting (Jer 1:10). Dry bones came to life (Ezek 37:1–14). The Persians defeated Babylon on October 29, 539 BC and Cyrus, the Persian king, allowed exiles to return. He even supported the rebuilding of Jerusalem’s temple (Ezra 1:1–4). Work began in 537 BC. Returnees constructed an altar and laid the temple’s foundation (Ezra 3). Then came the problems. Enemies “hired counselors to work against them and frustrate their plans during the entire reign of Cyrus king of Persia and down to the reign of Darius king of Persia.” (Ezra 4:5) Work did not resume until 520 BC. For seventeen years people walked past the same pile of cut timber, cedars from Lebanon, and hand-carved stones. -

The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Seminars Number 2

oi.uchicago.edu i THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ORIENTAL INSTITUTE SEMINARS NUMBER 2 Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu ii oi.uchicago.edu iii MARGINS OF WRITING, ORIGINS OF CULTURES edited by SETH L. SANDERS with contributions by Seth L. Sanders, John Kelly, Gonzalo Rubio, Jacco Dieleman, Jerrold Cooper, Christopher Woods, Annick Payne, William Schniedewind, Michael Silverstein, Piotr Michalowski, Paul-Alain Beaulieu, Theo van den Hout, Paul Zimansky, Sheldon Pollock, and Peter Machinist THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ORIENTAL INSTITUTE SEMINARS • NUMBER 2 CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu iv Library of Congress Control Number: 2005938897 ISBN: 1-885923-39-2 ©2006 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2006. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago Co-managing Editors Thomas A. Holland and Thomas G. Urban Series Editors’ Acknowledgments The assistance of Katie L. Johnson is acknowledged in the production of this volume. Front Cover Illustration A teacher holding class in a village on the Island of Argo, Sudan. January 1907. Photograph by James Henry Breasted. Oriental Institute photograph P B924 Printed by McNaughton & Gunn, Saline, Michigan The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Infor- mation Services — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. oi.uchicago.edu v TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................. -

Places and Peoples in Central Asia Graeco-Roman

PLACES AND PEOPLES IN CENTRAL ASIA AND IN THE GRAECO-ROMAN NEAR EAST ¥]-^µ A MULTILINGUAL GAZETTEER COMPILED FOR THE SERICA PROJECT FROM SELECT PRE-ISLAMIC SOURCES BY PROF. SAMUEL N.C. LIEU FRAS, FRHISTS, FSA, FAHA Visiting Fellow, Wolfson College, Cambridge and Inaugural Distinguished Professor in Ancient History, Macquarie University, Sydney ¥]-^µ ANCIENT INDIA AND IRAN TRUST (AIIT) CAMBRIDGE, UK AND ANCIENT CULTURES RESEARCH CENTRE (ACRC) MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY, NSW, AUSTRALIA (JULY, 2012) ABBREVIATIONS Acta Mari = The Acts of Mār Mārī the CPD = A Concise Pahlavi Dictionary, ed. Apostle, ed. and trans. A. Harrak D. MacKenzie (Oxford, 1971). (Atlanta, 2005). Ctes. = Ctesias. AI = Acta Iranica (Leiden – Téhéran- DCBT = W.E. Soothill and L. Hodous Liège 1974f.) (eds.) A Dictionary of Chinese Akk. = Akkadian (language). Buddhist Terms (London, 1934). Amm. = Ammianus Marcellinus. DB = Inscription of Darius at Behistan, cf. Anc. Lett. = Sogdian Ancient Letters, ed. OP 116-135. H. Reichelt, Die soghdischen DB (Akk.) = The Bisitun Inscription of Handschriften-reste des Britischen Darius the Great- Babylonian Version, Museums, 2 vols. (Heidelberg 1928- ed. E.N. von Voigtlander, CII, Pt. I, 1931), ii, 1-42. Vol. 2 (London, 1978). A?P = Inscription of Artaxerxes II or III at DB (Aram.) = The Bisitun Inscription of Persepolis, cf. OP 15-56. Darius the Great- Aramaic Version, Aram. = Aramaic (language). eds. J.C. Greenfield and B. Porten, CII, Arm. = Armenian (language). Pt. I, Vol. 5 (London, 1982). Arr. = Flavius Arrianus. Déd. = J.T. Milik, Dédicaces faites par Athan. Hist. Arian. = Athanasius, Historia des dieux (Palmyra, Hatra, Tyr et des Arianorum ad Monachos, PG 25.691- thiases sémitiques à l'époque romaine 796. -

The Western Kshatrapa Dāmazāda 173

THE WESTERN KSHATRAPA DĀMAZĀDA 173 The Western Kshatrapa Dāmazāda PANKAJ TANDON1 IN THEIR comprehensive survey of the coinage of the Western Kshatrapas, Jha and Rajgor2 (hereinafter J&R) argue that Rudradāman I had three sons who followed him in ruling their kingdom: J&R name them Dāmajadasri, Dāmaghsada, and Rudrasimha. In this J&R went against the view of Rapson who, in his catalogue of Western Kshatrapa coins in the British Museum,3 had speculated that Dāmajadasri and Dāmaghsada were in fact the same person. Most authors seem to have accepted Jha and Rajgor’s view.4 In this paper, I present new information that strengthens the argument that these ‘two’ rulers were indeed one, and that his name was Dāmazāda. Part of the argument involves a radical new proposal: that we can distinguish different mints for the Western Kshatrapa coinage. This innovation also helps resolve another century-old problem. The crux of the issue revolves around the fact that the name ‘Dāmaghsada’ as it is inscribed on the coins contains an unusual Brāhmī compound letter that is transliterated by most numismatists as ghsa. This letter appears also in the name of Chastana’s father, normally written as Ghsamotika. In the fi rst part of the paper, I argue that these names should be presented differently, as Zamotika and Dāmazāda, to better represent the way they must have been pronounced. The argument has two parts: fi rst, that the compound letter is in fact not ghsa but ysa, and, second, that this compound letter (regardless of whether it was written as ysa or ghsa) was intended to represent the foreign sound za for which Brāhmī had no representation.