Hypersonic Power Projection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Module 1: Hypersonic Atmosphere Lecture1: Characteristics of Hypersonic Atmosphere

NPTEL –Aerospace Module 1: Hypersonic Atmosphere Lecture1: Characteristics of Hypersonic Atmosphere 1.1 Introduction Hypersonic flight has special traits, some of which are seen in every hypersonic flight. Presence of these particular features during a flight is highly dependant on type of trajectory, configuration etc. In short it is the mission requirement which decides the nature of hypersonic atmosphere encountered by the flight vehicle. Some missions are designed for high deceleration in outer atmosphere during reentry. Hence, those flight vehicles experience longer flight duration at high angle of attacks due to which blunt nosed configuration are generally preferred for such aircrafts. On the contrary, some missions are centered on low flight duration with major deceleration closer to earth surface hence these vehicles have sharp nose and low angle of attack flights. Reentry flight path of hypersonic vehicle is thus governed by the parameters called as ballistic parameter and lifting parameter. These parameters are obtained by applying momentum conservation equation in the direction of the flight path and normal to it. Velocity-altitude map of the flight is thus made from the knowledge of these governing flight parameters, weight and surface area. Ballistic parameter is considered for non lifting reentry flights like flight path of Apollo capsule, however lifting parameter is considered for lifting reentry trajectories like that of space shuttle. Therefore hypersonic flight vehicles are classified in four different types based on the design constraints imposed from mission specifications. 1. Reentry Vehicles (RV): These vehicles are typically launched using rocket propulsion system. Reentry of these vehicles is controlled by control surfaces. -

Notes on Earth Atmospheric Entry for Mars Sample Return Missions

NASA/TP–2006-213486 Notes on Earth Atmospheric Entry for Mars Sample Return Missions Thomas Rivell Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California September 2006 The NASA STI Program Office . in Profile Since its founding, NASA has been dedicated to the • CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. Collected advancement of aeronautics and space science. The papers from scientific and technical confer- NASA Scientific and Technical Information (STI) ences, symposia, seminars, or other meetings Program Office plays a key part in helping NASA sponsored or cosponsored by NASA. maintain this important role. • SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientific, technical, The NASA STI Program Office is operated by or historical information from NASA programs, Langley Research Center, the Lead Center for projects, and missions, often concerned with NASA’s scientific and technical information. The subjects having substantial public interest. NASA STI Program Office provides access to the NASA STI Database, the largest collection of • TECHNICAL TRANSLATION. English- aeronautical and space science STI in the world. language translations of foreign scientific and The Program Office is also NASA’s institutional technical material pertinent to NASA’s mission. mechanism for disseminating the results of its research and development activities. These results Specialized services that complement the STI are published by NASA in the NASA STI Report Program Office’s diverse offerings include creating Series, which includes the following report types: custom thesauri, building customized databases, organizing and publishing research results . even • TECHNICAL PUBLICATION. Reports of providing videos. completed research or a major significant phase of research that present the results of NASA For more information about the NASA STI programs and include extensive data or theoreti- Program Office, see the following: cal analysis. -

Performances of a Small Hypersonic Airplane (Hyplane)

Politecnico di Torino Porto Institutional Repository [Proceeding] PERFORMANCES OF A SMALL HYPERSONIC AIRPLANE (HYPLANE) Original Citation: Savino R.; Russo G.; D’Oriano V.; Visone M.; Battipede M.; Gili P. (2014). PERFORMANCES OF A SMALL HYPERSONIC AIRPLANE (HYPLANE). In: 65th International Astronautical Congress„ Toronto, Canada, 29 September - 3 October 2014. pp. 1-13 Availability: This version is available at : http://porto.polito.it/2591763/ since: February 2015 Publisher: International Astronautical Federation (IAF) Terms of use: This article is made available under terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Article ("Public - All rights reserved") , as described at http://porto.polito.it/terms_and_conditions. html Porto, the institutional repository of the Politecnico di Torino, is provided by the University Library and the IT-Services. The aim is to enable open access to all the world. Please share with us how this access benefits you. Your story matters. (Article begins on next page) 65th International Astronautical Congress, Toronto, Canada. Copyright ©2014 by the Authors. Published by the IAF, with permission and released to the IAF to publish in all forms. IAC-14-D2.4 PERFORMANCES OF A SMALL HYPERSONIC AIRPLANE (HYPLANE) Raffaele Savino Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Naples “Federico II”, Italy Gennaro Russo Trans-Tech srl and Space Renaissance Italia, Italy Vera D’Oriano*, Michele Visone Blue Engineering, Italy Manuela Battipede, Piero Gili Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Polytechnic of Turin, Italy In the present work a preliminary performance study regarding a small hypersonic airplane named HyPlane is presented. It is designed for long duration sub-orbital space tourism missions, in the frame of the Space Renaissance (SR) Italia Space Tourism Program. -

Nasa X-15 Program

5 24,132 6 9 NASA X-15 PROGRAM By: T.D. Barnes - NASA Contractor - 1960s NASA contractors for the X-15 program were Bendix Field Engineering followed by Unitec, Inc. The NASA High Range Tracking stations were located at Ely and Beatty Nevada with main control being at Dryden/Edwards AFB in California. Personnel at the tracking stations consisted of a Station Manager, a Technical Advisor, and field engineers for the Mod-2 Radar, Data Transmission System, Communications, Telemetry, and Plant Maintenance/Generators. NASA had a site monitor at each tracking station to monitor our contractor operations. Though supporting flights of the X-15 was their main objective, they also participated in flights of the XB-70, the three Lifting Bodies, experimental Lunar Landing vehicles, and an occasional A-12/YF-12/SR-71 Blackbird flight. On mission days a NASA van picked up each member of the crew at their residence for the 4:20 a.m. trip to the tracking station 18 miles North of Beatty on the Tonopah Highway. Upon arrival each performed preflight calibrations and setup of their various systems. The liftoff of the B-52, with the X-15 tucked beneath its wing, seldom occurred after 9:00 a.m. due to the heat effect of the Mojave Desert making it difficult for the planes to acquire altitude. At approximately 0800 hours two pilots from Dryden would proceed uprange to evaluate the condition of the dry lake beds in the event of an emergency landing of the X-15 (always buzzing our station on the way up and back). -

Modelling a Hypersonic Single Expansion Ramp Nozzle of a Hypersonic Aircraft Through Parametric Studies

energies Article Modelling a Hypersonic Single Expansion Ramp Nozzle of a Hypersonic Aircraft through Parametric Studies Andrew Ridgway, Ashish Alex Sam * and Apostolos Pesyridis College of Engineering, Design and Physical Sciences, Brunel University London, London UB8 3PH, UK; [email protected] (A.R.); [email protected] (A.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-1895-267-901 Received: 26 September 2018; Accepted: 7 December 2018; Published: 10 December 2018 Abstract: This paper aims to contribute to developing a potential combined cycle air-breathing engine integrated into an aircraft design, capable of performing flight profiles on a commercial scale. This study specifically focuses on the single expansion ramp nozzle (SERN) and aircraft-engine integration with an emphasis on the combined cycle engine integration into the conceptual aircraft design. A parametric study using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) have been employed to analyze the sensitivity of the SERN’s performance parameters with changing geometry and operating conditions. The SERN adapted to the different operating conditions and was able to retain its performance throughout the altitude simulated. The expansion ramp shape, angle, exit area, and cowl shape influenced the thrust substantially. The internal nozzle expansion and expansion ramp had a significant effect on the lift and moment performance. An optimized SERN was assembled into a scramjet and was subject to various nozzle inflow conditions, to which combustion flow from twin strut injectors produced the best thrust performance. Side fence studies observed longer and diverging side fences to produce extra thrust compared to small and straight fences. Keywords: scramjet; single expansion ramp nozzle; hypersonic aircraft; combined cycle engines 1. -

Aerodynamic Characteristics of Two Waverider-Derived Hypersonic Cruise Configurations

NASA Technical Paper 3559 Aerodynamic Characteristics of Two Waverider-Derived Hypersonic Cruise Configurations Charles E. Cockrell, Jr., Lawrence D. Huebner, and Dennis B. Finley July 1996 NASA Technical Paper 3559 Aerodynamic Characteristics of Two Waverider-Derived Hypersonic Cruise Configurations Charles E. Cockrell, Jr. and Lawrence D. Huebner Langley Research Center • Hampton, Virginia Dennis B. Finley Lockheed-Fort Worth Company • Fort Worth, Texas National Aeronautics and Space Administration Langley Research Center • Hampton, Virginia 23681-0001 July 1996 Available electronically at the following URL address: http:lltechreports.larc.nasa.govlltrslitrs.html Printed copies available from the following: NASA Center for AeroSpace Information National Technical Information Service (NTIS) 800 Elkridge Landing Road 5285 Port Royal Road Linthicum Heights, MD 21090-2934 Springfield, VA 22161-2171 (301) 621-0390 (703) 487-4650 Abstract An evaluation was made of the effects of integrating the required aircraft compo- nents with hypersonic high-lift configurations known as waveriders to create hyper- sonic cruise vehicles. Previous studies suggest that waveriders offer advantages in aerodynamic performance and propulsionairframe integration (PAl) characteristics over conventional non-waverider hypersonic shapes. A wind-tunnel model was devel- oped that integrates vehicle components, including canopies, engine components, and control surfaces, with two pure waverider shapes, both conical-flow-derived wave- riders for a design Mach number of 4.0. Experimental data and limited computational fluid dynamics (CFD) solutions were obtained over a Mach number range of 1.6 to 4.63. The experimental data show the component build-up effects and the aero- dynamic characteristics of the fully integrated configurations, including control sur- face effectiveness. -

Science & Technology Trends 2020-2040

Science & Technology Trends 2020-2040 Exploring the S&T Edge NATO Science & Technology Organization DISCLAIMER The research and analysis underlying this report and its conclusions were conducted by the NATO S&T Organization (STO) drawing upon the support of the Alliance’s defence S&T community, NATO Allied Command Transformation (ACT) and the NATO Communications and Information Agency (NCIA). This report does not represent the official opinion or position of NATO or individual governments, but provides considered advice to NATO and Nations’ leadership on significant S&T issues. D.F. Reding J. Eaton NATO Science & Technology Organization Office of the Chief Scientist NATO Headquarters B-1110 Brussels Belgium http:\www.sto.nato.int Distributed free of charge for informational purposes; hard copies may be obtained on request, subject to availability from the NATO Office of the Chief Scientist. The sale and reproduction of this report for commercial purposes is prohibited. Extracts may be used for bona fide educational and informational purposes subject to attribution to the NATO S&T Organization. Unless otherwise credited all non-original graphics are used under Creative Commons licensing (for original sources see https://commons.wikimedia.org and https://www.pxfuel.com/). All icon-based graphics are derived from Microsoft® Office and are used royalty-free. Copyright © NATO Science & Technology Organization, 2020 First published, March 2020 Foreword As the world Science & Tech- changes, so does nology Trends: our Alliance. 2020-2040 pro- NATO adapts. vides an assess- We continue to ment of the im- work together as pact of S&T ad- a community of vances over the like-minded na- next 20 years tions, seeking to on the Alliance. -

GAO-21-378, HYPERSONIC WEAPONS: DOD Should Clarify

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Addressees March 2021 HYPERSONIC WEAPONS DOD Should Clarify Roles and Responsibilities to Ensure Coordination across Development Efforts GAO-21-378 March 2021 HYPERSONIC WEAPONS DOD Should Clarify Roles and Responsibilities to Ensure Coordination across Development Efforts Highlights of GAO-21-378, a report to congressional addressees Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found Hypersonic missiles, which are an GAO identified 70 efforts to develop hypersonic weapons and related important part of building hypersonic technologies that are estimated to cost almost $15 billion from fiscal years 2015 weapon systems, move at least five through 2024 (see figure). These efforts are widespread across the Department times the speed of sound, have of Defense (DOD) in collaboration with the Department of Energy (DOE) and, in unpredictable flight paths, and are the case of hypersonic technology development, the National Aeronautics and expected to be capable of evading Space Administration (NASA). DOD accounts for nearly all of this amount. today’s defensive systems. DOD has begun multiple efforts to develop Hypersonic Weapon-related and Technology Development Total Reported Funding by Type of offensive hypersonic weapons as well Effort from Fiscal Years 2015 through 2024, in Billions of Then-Year Dollars as technologies to improve its ability to track and defend against them. NASA and DOE are also conducting research into hypersonic technologies. The investments for these efforts are significant. This report identifies: (1) U.S. government efforts to develop hypersonic systems that are underway and their costs, (2) challenges these efforts face and what is being done to address them, and (3) the extent to which the U.S. -

Facing the Heat Barrier: a History of Hypersonics First Thoughts of Hypersonic Propulsion

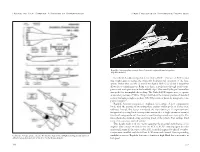

Facing the Heat Barrier: A History of Hypersonics First Thoughts of Hypersonic Propulsion Republic’s Aerospaceplane concept showed extensive engine-airframe integration. (Republic Aviation) For takeoff, Lockheed expected to use Turbo-LACE. This was a LACE variant that sought again to reduce the inherently hydrogen-rich operation of the basic system. Rather than cool the air until it was liquid, Turbo-Lace chilled it deeply but allowed it to remain gaseous. Being very dense, it could pass through a turbocom- pressor and reach pressures in the hundreds of psi. This saved hydrogen because less was needed to accomplish this cooling. The Turbo-LACE engines were to operate at chamber pressures of 200 to 250 psi, well below the internal pressure of standard rockets but high enough to produce 300,000 pounds of thrust by using turbocom- pressed oxygen.67 Republic Aviation continued to emphasize the scramjet. A new configuration broke with the practice of mounting these engines within pods, as if they were turbojets. Instead, this design introduced the important topic of engine-airframe integration by setting forth a concept that amounted to a single enormous scramjet fitted with wings and a tail. A conical forward fuselage served as an inlet spike. The inlets themselves formed a ring encircling much of the vehicle. Fuel tankage filled most of its capacious internal volume. This design study took two views regarding the potential performance of its engines. One concept avoided the use of LACE or ACES, assuming again that this craft could scram all the way to orbit. Still, it needed engines for takeoff so turbo- ramjets were installed, with both Pratt & Whitney and General Electric providing Lockheed’s Aerospaceplane concept. -

Aerodynamic Study of a Small Hypersonic Plane

Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II” Dottorato di Ricerca in Ingegneria Aerospaziale, Navale e della Qualità XXVII Ciclo Aerodynamic study of a small hypersonic plane Coordinatore: Ch.mo Prof. L. De Luca Candidata: Tutors: Ing. Vera D'Oriano Ch.mo Prof. R. Savino Ing. M. Visone (BLUE Engineering) Acknowledgements First I wish to thank my academic tutor Prof. Raffaele Savino, for offering me this precious opportunity and for his enthusiastic guidance. Next, I am immensely grateful to my company tutor, Michele Visone (Mike, for friends) for his technical support, despite his busy schedule, and for his constant encouragements. I also would like to thank the HyPlane team members: Rino Russo, Prof. Battipede and Prof. Gili, Francesco and Gennaro, for the fruitful collaborations. A special thank goes to all Blue Engineering guys (especially to Myriam) for making our site a pleasant and funny place to work. Many thanks to queen Giuly and Peppe "il pazzo", my adoptive family during my stay in Turin, and also to my real family, for the unconditional love and care. My greatest gratitude goes to my unique friends - my potatoes (Alle & Esa), my mentor Valerius and Franca - and to my soul mate Naso, to whom I dedicate this work. Abstract Access to Space is still in its early stages of commercialization. Most of the attention is currently focused on sub-orbital flights, which allow Space tourists to experiment microgravity conditions for a few minutes and to see a large area of the Earth, along with its curvature, from the stratosphere. Secondary markets directly linked to the commercial sub-orbital flights may include microgravity research, remote sensing, high altitude Aerospace technological testing and astronauts training, while a longer term perspective can also foresee point-to-point hypersonic transportation. -

The Lapcat-Mr2 Hypersonic Cruiser Concept

THE LAPCAT-MR2 HYPERSONIC CRUISER CONCEPT J. Steelant and T. Langener* * ESA-ESTEC, Keplerlaan 1, 2201 AZ Noordwijk, Netherlands Vehicle Design, Hypersonic Flight, Combined Cycle Engine, Dual-Mode Ramjet Abstract thus bringing the elliptical combustor cross section to a circular cross-section. During Ramjet-mode, this This paper describes the MR2, a Mach 8 nozzle was used as a combustor that thermally cruise passenger vehicle, conceptually designed for choked, allowing for supersonic expansion in the antipodal flight from Brussels to Sydney in less than second nozzle. The second nozzle itself was 4 hours. This is one of the different concepts studied streamtraced from an axisymmetric isentropic within the LAPCAT II project [1]. It is an evolution expansion and truncated to a suitable length. Both of a previous vehicle, the MR1 based upon a dorsal nozzles were designed for cruise conditions. mounted engine, as a result of multiple optimization The final vehicle is shown below in Figure 1 iterations [2] leading to the MR2.4 concepts. The while specific details of the design are expanded main driver was the optimal integration of a high upon in the next section. performance propulsion unit within an aerodynamically efficient wave rider design, whilst guaranteeing sufficient volume for tankage, payload and other subsystems. Introduction The aerodynamics for the MR2 is a waverider form based upon an adapted osculating cone method enabling to construct the vehicle from the leading edge while reducing integration problems between the aerodynamics and the intake. The intake was constructed using Figure 1 MR2 Vehicle streamtracing methods from an axisymmetric inward turning compression surface and was integrated on top of the waverider in a dorsal layout. -

Contacts: Isabel Morales, Museum of Science and Industry, (773) 947-6003 Renee Mailhiot, Museum of Science and Industry, (773) 947-3133

Contacts: Isabel Morales, Museum of Science and Industry, (773) 947-6003 Renee Mailhiot, Museum of Science and Industry, (773) 947-3133 A GLOSSARY OF TERMS Aerodynamics: The study of the properties of moving air, particularly of the interaction between the air and solid bodies moving through it. Afterburner: An auxiliary burner fitted to the exhaust system of a turbojet engine to increase thrust. Airfoil: A structure with curved surfaces designed to give the most favorable ratio of lift to drag in flight, used as the basic form of the wings, fins and horizontal stabilizer of most aircraft. Armstrong limit: The altitude that produces an atmospheric pressure so low (0.0618 atmosphere or 6.3 kPa [1.9 in Hg]) that water boils at the normal temperature of the human body: 37°C (98.6°F). The saliva in your mouth would boil if you were not wearing a pressure suit at this altitude. Death would occur within minutes from exposure to the vacuum. Autothrottle: The autopilot function that increases or decreases engine power,typically on larger aircraft. Avatar: An icon or figure representing a particular person in computer games, Internet forums, etc. Aerospace: The branch of technology and industry concerned with both aviation and space flight. Carbon fiber: Thin, strong, crystalline filaments of carbon, used as a strengthening material, especially in resins and ceramics. Ceres: A dwarf planet that orbits within the asteroid belt and the largest asteroid in the solar system. Chinook: The Boeing CH-47 Chinook is an American twin-engine, tandem-rotor heavy-lift helicopter. CST-100: The crew capsule spacecraft designed by Boeing in collaboration with Bigelow Aerospace for NASA's Commercial Crew Development program.