A History of the East Indian Indentured Plantation Worker in Trinidad, 1845-1917

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

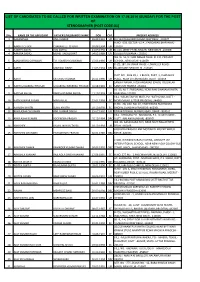

Stenographer (Post Code-01)

LIST OF CANDIDATES TO BE CALLED FOR WRITTEN EXAMINATION ON 17.08.2014 (SUNDAY) FOR THE POST OF STENOGRAPHER (POST CODE-01) SNo. NAME OF THE APPLICANT FATHER'S/HUSBAND'S NAME DOB CAT. PRESENT ADDRESS 1 AAKANKSHA ANIL KUMAR 28.09.1991 UR B II 544 RAGHUBIR NAGAR NEW DELHI -110027 H.NO. -539, SECTOR -15-A , FARIDABAD (HARYANA) - 2 AAKRITI CHUGH CHARANJEET CHUGH 30.08.1994 UR 121007 3 AAKRITI GOYAL AJAI GOYAL 21.09.1992 UR B -116, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI -110008 4 AAMIRA SADIQ MOHD. SADIQ BHAT 04.05.1989 UR GOOSU PULWAMA - 192301 WZ /G -56, UTTAM NAGAR NEAR, M.C.D. PRIMARY 5 AANOUKSHA GOSWAMI T.R. SOMESH GOSWAMI 15.03.1995 UR SCHOOL, NEW DELHI -110059 R -ZE, 187, JAI VIHAR PHASE -I, NANGLOI ROAD, 6 AARTI MAHIPAL SINGH 21.03.1994 OBC NAJAFGARH NEW DELHI -110043 PLOT NO. -28 & 29, J -1 BLOCK, PART -1, CHANAKYA 7 AARTI SATENDER KUMAR 20.01.1990 UR PLACE, NEAR UTTAM NAGAR, DELHI -110059 SANJAY NAGAR, HOSHANGABAD (GWOL TOLI) NEAR 8 AARTI GULABRAO THOSAR GULABRAO BAKERAO THOSAR 30.08.1991 SC SANTOSHI TEMPLE -461001 I B -35, N.I.T. FARIDABAD, NEAR RAM DHARAM KANTA, 9 AASTHA AHUJA RAKESH KUMAR AHUJA 11.10.1993 UR HARYANA -121001 VILL. -MILAK TAJPUR MAFI, PO. -KATHGHAR, DISTT. - 10 AATIK KUMAR SAGAR MADAN LAL 22.01.1993 SC MORADABAD (UTTAR PRADESH) -244001 H.NO. -78, GALI NO. 02, KHATIKPURA BUDHWARA 11 AAYUSHI KHATRI SUNIL KHATRI 10.10.1993 SC BHOPAL (MADHYA PRADESH) -462001 12 ABHILASHA CHOUHAN ANIL KUMAR SINGH 25.07.1992 UR RIYASAT PAWAI, AURANGABAD, BIHAR - 824101 VILL. -

An Overview of Hakka Migration History: Where Are You From?

客家 My China Roots & CBA Jamaica An overview of Hakka Migration History: Where are you from? July, 2016 www.mychinaroots.com & www.cbajamaica.com 15 © My China Roots An Overview of Hakka Migration History: Where Are You From? Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................... 3 Five Key Hakka Migration Waves............................................................................................. 3 Mapping the Waves ....................................................................................................................... 3 First Wave: 4th Century, “the Five Barbarians,” Jin Dynasty......................................................... 4 Second Wave: 10th Century, Fall of the Tang Dynasty ................................................................. 6 Third Wave: Late 12th & 13th Century, Fall Northern & Southern Song Dynasties ....................... 7 Fourth Wave: 2nd Half 17th Century, Ming-Qing Cataclysm .......................................................... 8 Fifth Wave: 19th – Early 20th Century ............................................................................................. 9 Case Study: Hakka Migration to Jamaica ............................................................................ 11 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 11 Context for Early Migration: The Coolie Trade........................................................................... -

Spanish, French, Dutch, Andamerican Patriots of Thb West Indies During

Spanish, French, Dutch, andAmerican Patriots of thb West Indies i# During the AMERICAN Revolution PART7 SPANISH BORDERLAND STUDIES By Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough -~ ,~~~.'.i~:~ " :~, ~i " .... - ~ ,~ ~"~" ..... "~,~~'~~'-~ ,%v t-5.._. / © Copyright ,i. "; 2001 ~(1 ~,'~': .i: • by '!!|fi:l~: r!;.~:! Granville W. and N. C. Hough 3438 Bahia Blanca West, Apt B ~.l.-c • Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 !LI.'.. Email: gwhough(~earthiink.net u~ "~: .. ' ?-' ,, i.. Other books in this series include: • ...~ , Svain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the.American Revolution, Part 1, 1998. ,. Sp~fin's Califomi0 Patriqts in its 1779-1783 Wor with Englgnd - During the American Revolution, Part 2, :999. Spain's Arizona Patriots in ire |779-1783 War with Engl~n~i - During the Amcricgn RevolutiQn, Third Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Svaln's New Mexico Patriots in its 1779-|783 Wit" wi~ England- During the American Revolution, Fourth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Spain's Texa~ patriot~ in its 1779-1783 War with Enaland - Daring the A~a~ri~n Revolution, Fifth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 2000. Spain's Louisi~a Patriots in its; 1779-1783 War witil England - During.the American Revolution, Sixth StUdy of the Spanish Borderlands, 20(~0. ./ / . Svain's Patriots of Northerrt New Svain - From South of the U. S. Border - in its 1779- 1783 War with Engl~nd_ Eighth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, coming soon. ,:.Z ~JI ,. Published by: SHHAK PRESS ~'~"'. ~ ~i~: :~ .~:,: .. Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research ~.,~.,:" P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 (714) 894-8161 ~, ~)it.,I ,. -

India in the Indian Ocean Donald L

Naval War College Review Volume 59 Article 6 Number 2 Spring 2006 India in the Indian Ocean Donald L. Berlin Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Berlin, Donald L. (2006) "India in the Indian Ocean," Naval War College Review: Vol. 59 : No. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol59/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen Berlin: India in the Indian Ocean INDIA IN THE INDIAN OCEAN Donald L. Berlin ne of the key milestones in world history has been the rise to prominence Oof new and influential states in world affairs. The recent trajectories of China and India suggest strongly that these states will play a more powerful role in the world in the coming decades.1 One recent analysis, for example, judges that “the likely emergence of China and India ...asnewglobal players—similar to the advent of a united Germany in the 19th century and a powerful United States in the early 20th century—will transform the geopolitical landscape, with impacts potentially as dramatic as those in the two previous centuries.”2 India’s rise, of course, has been heralded before—perhaps prematurely. How- ever, its ascent now seems assured in light of changes in India’s economic and political mind-set, especially the advent of better economic policies and a diplo- macy emphasizing realism. -

20010629, House Debates

29 Ombudsman Report Friday, June 29, 2001 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Friday, June 29, 2001 The House met at 1.30 p.m. PRAYERS [MR. SPEAKER in the Chair] OMBUDSMAN REPORT (TWENTY-THIRD) Mr. Speaker: Hon. Members, I have received the 23rd Annual Report of the Ombudsman for the period January 01, 2000—December 31, 2000. The report is laid on the table of the House. CONDOLENCES (Mr. Tahir Kassim Ali) Mr. Speaker: Hon. Members, it is disheartening that I announce the passing of a former representative of this honourable House, Mr. Tahir Kassim Ali. I wish to extend condolences to the bereaved family. Members of both sides of the House may wish to offer condolences to the family. The Attorney General and Minister of Legal Affairs (Hon. Ramesh Lawrence Maharaj): Mr. Speaker, the deceased, Mr. Tahir Ali served this Parliament from the period 1971—1976. He was the elected Member of Parliament for Couva. He resided in the constituency of Couva South. In addition to being a Member of Parliament, he was also a Councillor for the Couva electoral district in the Caroni County Council for the period 1968—1971. He served as Member of Parliament and Councillor as a member of the People’s National Movement. In 1974 he deputized for the hon. Shamshuddin Mohammed, now deceased, as Minister of Public Utilities for a period of time. In 1991, Mr. Tahir Ali assisted the United National Congress in the constituency of Couva South for the general election of that year. He would be remembered as a person who saw the light and came to the United National Congress. -

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago De Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago de Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Jesse E. Hoffnung-Garskof, Co-Chair Professor Rebecca J. Scott, Co-Chair Associate Professor Paulina L. Alberto Professor Emerita Gillian Feeley-Harnik Professor Jean M. Hébrard, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Professor Martha Jones To Paul ii Acknowledgments One of the great joys and privileges of being a historian is that researching and writing take us through many worlds, past and present, to which we become bound—ethically, intellectually, emotionally. Unfortunately, the acknowledgments section can be just a modest snippet of yearlong experiences and life-long commitments. Archivists and historians in Cuba and Spain offered extremely generous support at a time of severe economic challenges. In Havana, at the National Archive, I was privileged to get to meet and learn from Julio Vargas, Niurbis Ferrer, Jorge Macle, Silvio Facenda, Lindia Vera, and Berta Yaque. In Santiago, my research would not have been possible without the kindness, work, and enthusiasm of Maty Almaguer, Ana Maria Limonta, Yanet Pera Numa, María Antonia Reinoso, and Alfredo Sánchez. The directors of the two Cuban archives, Martha Ferriol, Milagros Villalón, and Zelma Corona, always welcomed me warmly and allowed me to begin my research promptly. My work on Cuba could have never started without my doctoral committee’s support. Rebecca Scott’s tireless commitment to graduate education nourished me every step of the way even when my self-doubts felt crippling. -

Henry Clinton Papers, Volume Descriptions

Henry Clinton Papers William L. Clements Library Volume Descriptions The University of Michigan Finding Aid: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsead/umich-wcl-M-42cli?view=text Major Themes and Events in the Volumes of the Chronological Series of the Henry Clinton papers Volume 1 1736-1763 • Death of George Clinton and distribution of estate • Henry Clinton's property in North America • Clinton's account of his actions in Seven Years War including his wounding at the Battle of Friedberg Volume 2 1764-1766 • Dispersal of George Clinton estate • Mary Dunckerley's account of bearing Thomas Dunckerley, illegitimate child of King George II • Clinton promoted to colonel of 12th Regiment of Foot • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot Volume 3 January 1-July 23, 1767 • Clinton's marriage to Harriet Carter • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton's property in North America Volume 4 August 14, 1767-[1767] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Relations between British and Cherokee Indians • Death of Anne (Carle) Clinton and distribution of her estate Volume 5 January 3, 1768-[1768] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton discusses military tactics • Finances of Mary (Clinton) Willes, sister of Henry Clinton Volume 6 January 3, 1768-[1769] • Birth of Augusta Clinton • Henry Clinton's finances and property in North America Volume 7 January 9, 1770-[1771] • Matters concerning the 12th Regiment of Foot • Inventory of Clinton's possessions • William Henry Clinton born • Inspection of ports Volume 8 January 9, 1772-May -

1 the REPUBLIC of TRINIDAD and TOBAGO in the HIGH COURT of JUSTICE Claim No. CV2008-02265 BETWEEN BASDEO PANDAY OMA PANDAY Claim

THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE Claim No. CV2008-02265 BETWEEN BASDEO PANDAY OMA PANDAY Claimants AND HER WORSHIP MS. EJENNY ESPINET Defendant AND DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS Interested Party Before the Honorable Mr. Justice V. Kokaram Appearances: Mr. G. Robertson Q.C., Mr. R. Rajcoomar and Mr. A. Beharrylal instructed by Ms. M. Panday for the Claimants Mr. N. Byam for Her Worship Ms. Ejenny Espinet Mr. D. Mendes, S.C. and Mr. I. Benjamin instructed by Ms. R. Maharaj for the Interested Party 1 JUDGMENT 1. Introduction: 1.1 Mr. Basdeo Panday (“the first Claimant”) is one of the veterans in the political life of Trinidad and Tobago. He is the political leader of the United National Congress Alliance (“UNC-A”), the member of Parliament for the constituency of Couva North in the House of Representatives, the Leader of the Opposition in the Parliament of Trinidad and Tobago and former Prime Minister of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago 1. He has been a member of the House of Representatives since 1976 and in 1991 founded the United National congress (“UNC”) the predecessor to the UNC-A. He together with his wife, Oma Panday (“the second Claimant”) were both charged with the indictable offence of having committed an offence under the Prevention of Corruption Act No. 11 of 1987 namely: that on or about 30 th December 1998, they corruptly received from Ishwar Galbaransingh and Carlos John, an advantage in the sum of GBP 25,000 as a reward on account for the first Claimant, for favouring the interests of Northern Construction Limited in relation to the construction of the then new Piarco International Airport 2. -

Two Centuries of International Migration

IZA DP No. 7866 Two Centuries of International Migration Joseph P. Ferrie Timothy J. Hatton December 2013 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Two Centuries of International Migration Joseph P. Ferrie Northwestern University Timothy J. Hatton University of Essex, Australian National University and IZA Discussion Paper No. 7866 December 2013 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. -

The Marine East Indies: Diversity and ARTICLE Speciation John C

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2005) 32, 1517–1522 ORIGINAL The marine East Indies: diversity and ARTICLE speciation John C. Briggs* Georgia Museum of Natural History, The ABSTRACT University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA Aim To discuss the impact of new diversity information and to utilize recent findings on modes of speciation in order to clarify the evolutionary significance of the East Indies Triangle. Location The Indo-Pacific Ocean. Methods Analysis of information on species diversity, distribution patterns and speciation for comparative purposes. Results Information from a broad-scale survey of Indo-Pacific fishes has provided strong support for the theory that the East Indies Triangle has been operating as a centre of origin. It has become apparent that more than two-thirds of the reef fishes inhabiting the Indo-Pacific are represented in the Triangle. An astounding total of 1111 species, more than are known from the entire tropical Atlantic, were reported from one locality on the small Indonesian island of Flores. New information on speciation modes indicates that the several unique characteristics of the East Indian fauna are probably due to the predominance of competitive (sympatric) speciation. Main conclusions It is proposed that, within the East Indies, the high species diversity, the production of dominant species, and the presence of newly formed species, are due to natural selection being involved in reproductive isolation, the first step in the sympatric speciation process. In contrast, speciation in the peripheral areas is predominately allopatric. Species formed by allopatry are the direct result of barriers to gene flow. In this case, reproductive isolation may be seen as a physical process that does not involve natural selection. -

List of Organisations/Individuals Who Sent Representations to the Commission

1. A.J.K.K.S. Polytechnic, Thoomanaick-empalayam, Erode LIST OF ORGANISATIONS/INDIVIDUALS WHO SENT REPRESENTATIONS TO THE COMMISSION A. ORGANISATIONS (Alphabetical Order) L 2. Aazadi Bachao Andolan, Rajkot 3. Abhiyan – Rural Development Society, Samastipur, Bihar 4. Adarsh Chetna Samiti, Patna 5. Adhivakta Parishad, Prayag, Uttar Pradesh 6. Adhivakta Sangh, Aligarh, U.P. 7. Adhunik Manav Jan Chetna Path Darshak, New Delhi 8. Adibasi Mahasabha, Midnapore 9. Adi-Dravidar Peravai, Tamil Nadu 10. Adirampattinam Rural Development Association, Thanjavur 11. Adivasi Gowari Samaj Sangatak Committee Maharashtra, Nagpur 12. Ajay Memorial Charitable Trust, Bhopal 13. Akanksha Jankalyan Parishad, Navi Mumbai 14. Akhand Bharat Sabha (Hind), Lucknow 15. Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha, New Delhi 16. Akhil Bharatiya Adivasi Vikas Parishad, New Delhi 17. Akhil Bharatiya Baba Saheb Dr. Ambedkar Samaj Sudhar Samiti, Basti, Uttar Pradesh 18. Akhil Bharatiya Baba Saheb Dr. Ambedkar Samaj Sudhar Samiti, Mirzapur 19. Akhil Bharatiya Bhil Samaj, Ratlam District, Madhya Pradesh 20. Akhil Bharatiya Bhrastachar Unmulan Avam Samaj Sewak Sangh, Unna, Himachal Pradesh 21. Akhil Bharatiya Dhan Utpadak Kisan Mazdoor Nagrik Bachao Samiti, Godia, Maharashtra 22. Akhil Bharatiya Gwal Sewa Sansthan, Allahabad. 23. Akhil Bharatiya Kayasth Mahasabha, Amroh, U.P. 24. Akhil Bharatiya Ladhi Lohana Sindhi Panchayat, Mandsaur, Madhya Pradesh 25. Akhil Bharatiya Meena Sangh, Jaipur 26. Akhil Bharatiya Pracharya Mahasabha, Baghpat,U.P. 27. Akhil Bharatiya Prajapati (Kumbhkar) Sangh, New Delhi 28. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtrawadi Hindu Manch, Patna 29. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtriya Brahmin Mahasangh, Unnao 30. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtriya Congress Alap Sankyak Prakosht, Lakheri, Rajasthan 31. Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Congress, Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan 32. Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Congress, Mumbai 33. -

Anglo-Indians: the Dilemma of Identity

ANGLO-INDIANS: THE DILEMMA OF IDENTITY Sheila Pais James Department of Sociology Flinders University of S.A. Paper presented at Counterpoints Flinders University Postgraduate Conference South Australia 19 -20 April 2001 E-mail Sheila James: [email protected] ABSTRACT On the eve of departure of the British from India, the Anglo-Indians found themselves in an invidious situation - caught between the European attitude of superiority towards Indian and Anglo-Indian alike and the Indian mistrust of them, due to their aloofness and their Western - oriented culture. One of the problems the Anglo-Indian community has always faced is one of ‘Identity’. In the early days of the colonial rule it was difficult for the Anglo-Indians to answer with certainty the question "Who am I?" As a genuine community consciousness developed this identity dilemma lessened but it was never firmly resolved. With the British leaving India and as opportunities for a resolution of identity conflict through migration faded a new identity orientation was necessary. Many Anglo-Indians, who were unable to make such a turn-about of identity and feeling insecure without the protective imperial umbrella, opted to leave India. Thus, victims of dilemma and indiscretion throughout their existence thousands of Anglo-Indians left for safe shores - Britain, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. For Anglo-Indians who have left India and settled abroad a similar problem of Identity again arises. IJAIS Vol. 7, No. 1. 2003, p. 3-17 www.international-journal-of-anglo-indian-studies.org Anglo-Indians: The Dilemma of Identity 4 INTRODUCTION This paper is a preliminary outline of the discourses surrounding the Anglo-Indians and their Dilemma of Identity.