“I Did Not Have...”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Professionalization of Green Parties?

Professionalization of Green parties? Analyzing and explaining changes in the external political approach of the Dutch political party GroenLinks Lotte Melenhorst (0712019) Supervisor: Dr. A. S. Zaslove 5 September 2012 Abstract There is a relatively small body of research regarding the ideological and organizational changes of Green parties. What has been lacking so far is an analysis of the way Green parties present them- selves to the outside world, which is especially interesting because it can be expected to strongly influence the image of these parties. The project shows that the Dutch Green party ‘GroenLinks’ has become more professional regarding their ‘external political approach’ – regarding ideological, or- ganizational as well as strategic presentation – during their 20 years of existence. This research pro- ject challenges the core idea of the so-called ‘threshold-approach’, that major organizational changes appear when a party is getting into government. What turns out to be at least as interesting is the ‘anticipatory’ adaptations parties go through once they have formulated government participation as an important party goal. Until now, scholars have felt that Green parties are transforming, but they have not been able to point at the core of the changes that have taken place. Organizational and ideological changes have been investigated separately, whereas in the case of Green parties organi- zation and ideology are closely interrelated. In this thesis it is argued that the external political ap- proach of GroenLinks, which used to be a typical New Left Green party but that lacks governmental experience, has become more professional, due to initiatives of various within-party actors who of- ten responded to developments outside the party. -

Woods Was Considering Nationalization Fortis Already for the Summer

[Unofficial Translation of Article] De Standaard, Bos wou Fortis Nederland voor de zomer al kopen, 10/12/2008 (Translated). http://www.standaard.be/cnt/cv23r142 Woods was considering nationalization Fortis already for the summer By Finance Minister Wouter Bos had considered the idea for summer to nationalize Fortis. That he says this week in Smoking Netherlands. ' For the summer and I found that with Fortis Nout Wellink did not go well. That tension could arise between the interests of Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and the top of the group. And that we should act very quickly in a situation like this. When I have the option already considered that the State could take over the Dutch part of Fortis. I have always thought: if it is necessary, then we do it. ' The pronunciation of forest comes as a surprise. Until now it was believed that the idea of nationalising the bank only at the end of september, just before the takeover. ' Jan Peter is a very good negotiator ' In the interview in the winter issue of Netherlands Wouter Bos also looks back on the Free negotiations on the nationalization of Fortis and ABN Amro. Wouter Bos and Prime Minister Balkenende, previously at two Cabinet formations as rivals were sitting opposite each other, now had to defend the Dutch interest in unison. ' I have at one point against Jan Peter said: you have to use all the tricks that you have in the formation used against me. ' According to woodland can protest loudly Balkende in negotiations: ' if the opposing team says something where he did not agree, he literally sitting briesen and puffing and say it's all nothing is. -

De Digitale Schandpaal De Invloed Van Internet Op Het Verloop Van Affaires En Schandalen

118 | Peter L. M. Vasterman* De digitale schandpaal De invloed van internet op het verloop van affaires en schandalen ‘De geschiedenis van het schandaal is dus een onderdeel van de geschiedenis van de openbaarheid.’ (De Swaan, 1996: 28). Door de opkomst van internet is het schandaal niet meer exclusief het domein van de professionele media. Aan de hand van vier actuele cases (Demmink, Depla, Duyvendak en Herfkens) is de invloed onderzocht van diverse types websites op de verschillende stadia waarin een affaire zich ontwikkelt tot schandaal. Vooral de interactie tussen de semipro- fessionele blogs en de nieuwsmedia is van belang, de rol van de inter- netgebruiker beperkt zich tot het (verontwaardigd) reageren op de ont- hullingen. Inleiding In 17 januari 1998 maakt Matt Drudge op zijn weblog Drudge Report 1 bekend dat Newsweek op het laatste moment heeft afgezien van publicatie van een onthulling over president Clinton, die een verhouding zou hebben met een stagiaire in het Witte Huis. Newsweek wil eerst nog meer feiten verifiëren, maar voor Drudge is dat geen reden om niet meteen te publiceren (Bosscher, 2007: 104). Als het verhaal eenmaal op straat ligt, kunnen de andere media niet achterblijven en binnen de kortste keren is het Lewinsky-schandaal een feit (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 1999: 13). Met één klap wordt duidelijk dat internet de spelregels heeft veranderd en dat ook een relatief onbekende eenmanssite met roddel- en shownieuws in staat is een schandaal te lanceren. Een kleine tien jaar later, eind november 2007 raakt de Nijmeegse wethouder Paul Depla in opspraak na onthullingen op weblog Geenstijl.nl2 dat beveiligingscamera’s * Dr. -

University of Groningen Van De Straat Naar De Staat? Groenlinks 1990-2010 Lucardie, Anthonie; Voerman, Gerrit

University of Groningen Van de straat naar de staat? GroenLinks 1990-2010 Lucardie, Anthonie; Voerman, Gerrit IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2010 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Lucardie, A. P. M., & Voerman, G. (editors) (2010). Van de straat naar de staat? GroenLinks 1990-2010. Amsterdam: Boom. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 10-02-2018 Van de straat naar de staat Paul Lucardie en Gerrit Voerman (redactie) Van de straat naar de staat GroenLinks 1990-2010 Boom – Amsterdam Tenzij anders vermeld zijn de affiches afkomstig van het Documentatiecentrum Nederlandse Politieke Partijen van de Rijksuniversiteit, Groningen. Afbeelding omslag: Utrecht, 19 februari 2010, in de aanloop naar de gemeenteraadsverkiezingen (foto: Bert Spiertz/Hollandse Hoogte). -

Bijlage 2 Opdracht, Samenstelling Commissie En Activiteiten

BIJLAGE 2 Opdracht, samenstelling commissie en activiteiten OPDRACHT EVALUATIECOMMISSIE Olof van der Gaag Manager Communicatie & Fondswerving Natuur & Milieu september 2012 Olof werkte van 1998 tot 2007 voor de Tweede-Kamerfractie van GroenLinks, eerst als beleidsmedewerker onderwijs, De commissie zal de verkiezingsuitslag van GroenLinks later als politiek coördinator. Daarvoor vice-voorzitter LSVb. in september 2012 onderzoeken. De factoren die sinds de verkiezingen van 2010 hebben geleid tot het slechte Wim Hazeu resultaat zullen onder de loep worden genomen: de Directeur-bestuurder Wonen Limburg, lid algemeen bestuur cultuur van en de verhoudingen binnen de organisatie, Aedes politieke positiebepaling en de onderliggende waarden, het Oud gemeenteraadslid (1998-2002) en voormalig wethouder functioneren van de top van de organisatie, het veranderend Stadsbeheer, mobiliteit en milieu (2002-2010) te Maastricht. politieke landschap en de verbondenheid van de partij Hiervoor werkzaam bij de Provincie Limburg en jarenlange met haar kiezers. Het zijn zaken die mogelijk verder terug actief voor de Vereniging Milieudefensie. gaan dan 2010. De commissie vat 2010 dan ook op als richtsnoer en niet als keiharde grens. De commissie zal de Hans Paul Klijnsma leden van GroenLinks betrekken bij haar onderzoek door Projectleider Groninger Forum, bestuurslid Natuur en met een aantal leden, zowel hoofdrolspelers als anderen, te Milieufederatie Groningen spreken. Vele leden hebben zich inmiddels via diverse media Van 1996 tot 2010 lid van de Groningse gemeenteraad, oud uitgelaten over de verkiezingsnederlaag. Ook die berichten lid partijraad en oud bestuurslid (penningmeester) afdeling zullen betrokken worden in de analyse. Tevens zal een Groningen. kiezersonderzoek worden gedaan naar motieven om deze keer niet of wel op GroenLinks te stemmen. -

Rondblik 2008

NIEUWSBRIEF VAN DE STICHTINGEN GKVG EN COZA Secretariaat: Postbus 1177 - 3860 BD Nijkerk Secretaris: Simon C. Bax - Tel.: 033 - 2465497 ISSN: 1877-1017 Rabobank: 1130.63.237 Postbank: 3930924 nr. 115, december 2008 KvK nr.: 41197673 KvK nr.: 41922225 [email protected] [email protected] Rondblik 2008 Door ds. L.J. Geluk sen in de V.S. niet meer kon voldoen aan hypo- Wie een berg beklimt, of – wat rustiger: bestijgt, thecaire verplichtingen (en hoe kwam dat eigen- blijft af en toe eens even stilstaan om van de lijk?), heeft als een domino-effect gewerkt: de klim te bekomen en naar beneden te kijken, ene bank na de andere viel om, de beurs zakte naar de route die werd afgelegd. Men kijkt dan weg, bedrijven hebben de poort moeten sluiten ook eens om zich heen naar de directe omge- en gingen failliet of verkeren in een deplorabele ving en dan weer naar boven, want je bent nog toestand, ontslagen vielen en zullen nog vallen. niet waar je komen wilt. En het ziet er naar uit dat het einde van deze Een moment om eens even stil te staan en om beweging nog niet is bereikt. Hieruit blijkt op zich heen te kijken is een jaarwisseling. Er veran- hoe ongezonde wijze met ‘het grote geld’ en dert dan niet veel, alleen het jaartal verspringt. kredieten is en wordt omgegaan. Veel ‘gebak- Maar toch… ken lucht’, zegt men dan. Op onverantwoorde Zo is nú de overgang van 2008 naar 2009 een wijze heeft de reclame-industrie de mensen moment om even terug te zien en om zich heen opgejaagd (en zij blijft dat doen) om te kopen, te kijken. -

Personalization of Political Newspaper Coverage: a Longitudinal Study in the Dutch Context Since 1950

Personalization of political newspaper coverage: a longitudinal study in the Dutch context since 1950 Ellis Aizenberg, Wouter van Atteveldt, Chantal van Son, Franz-Xaver Geiger VU University, Amsterdam This study analyses whether personalization in Dutch political newspaper coverage has increased since 1950. In spite of the assumption that personalization increased over time in The Netherlands, earlier studies on this phenomenon in the Dutch context led to a scattered image. Through automatic and manual content analyses and regression analyses this study shows that personalization did increase in The Netherlands during the last century, the changes toward that increase however, occurred earlier on than expected at first. This study also shows that the focus of reporting on politics is increasingly put on the politician as an individual, the coverage in which these politicians are mentioned however became more substantive and politically relevant. Keywords: Personalization, content analysis, political news coverage, individualization, privatization Introduction When personalization occurs a focus is put on politicians and party leaders as individuals. The context of the news coverage in which they are mentioned becomes more private as their love lives, upbringing, hobbies and characteristics of personal nature seem increasingly thoroughly discussed. An article published in 1984 in the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf forms a good example here, where a horse race betting event, which is attended by several ministers accompanied by their wives and girlfriends is carefully discussed1. Nowadays personalization is a much-discussed phenomenon in the field of political communication. It can simply be seen as: ‘a process in which the political weight of the individual actor in the political process increases 1 Ererondje (17 juli 1984). -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Radboud Repository PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/95225 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-06 and may be subject to change. Gebruiker: TeldersCommunity Eerlijk is eerlijk Wat een liberaal van de staat mag verwachten en van zichzelf moet vergen Marcel Wissenburg (voorzitter), Fleur de Beaufort, Patrick van Schie en Mark van de Velde Prof.mr. B.M. Teldersstichting Den Haag, 2011 Gebruiker: TeldersCommunity Prof.mr. B.M. Teldersstichting Koninginnegracht 55a 2514 AE Den Haag Telefoon (070) 363 1948 Fax (070) 363 1951 E-mail: [email protected] www.teldersstichting.nl Copyright © Teldersstichting – Den Haag Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij electronisch, mechanisch, door fotokopieën, opnamen, of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. Zetwerk en druk: Oranje/Van Loon B.V. ISBN/EAN: 978-90-73896-48-2 Trefwoorden: liberalisme, eerlijkheid, rechtvaardigheid, beloningen, belastingen, strafrecht, internationale orde Prijs: € 17,50 Gebruiker: TeldersCommunity Voorwoord Op 1 december 1994 vierde de Teldersstichting haar veertigjarig bestaan met een symposium ‘Liberalisme, conservatisme en communitarisme’. In de jaren daar- voor hadden de ‘communitaristen’ (gemeenschapsdenkers) school gemaakt, voor- al in de Verenigde Staten, met de bewering dat het liberalisme door het individu centraal te stellen en door zich in de politiek te richten op wetten en procedures, te leeg is om een samenleving de benodigde samenhang te verschaffen. -

Wie We Zijn En Wat We Willen

‘Groene en sociale politiek kan alleen vorm krijgen als we bereid zijn te sleutelen aan ons economische systeem, dat is de kern van mijn redenering. Het sociale evenwicht Wie we zijn en is dankzij de neoliberale golf van de laatste decennia volstrekt uit het lood geslagen, de ecologische balans raakt steeds verder zoek. Het herstellen van dit evenwicht is zeer urgent en de kerntaak van groene partijen.’ wat we willen ‘GroenLinks noemde zichzelf de afgelopen jaren vaak “een ideeënpartij Een politieke plaatsbepaling voor GroenLinks op zoek naar macht”. De ideeën, ook de non-conformistische, maakten de partij tot een aantrekkelijke broedplaats. GroenLinks is altijd een partij met lef geweest. Een partij ook, die alternatieven presenteerde en oplossingen aanbood. Meer dan ooit hebben we deze eigenschappen nodig om veel mensen aan ons te binden en met onze ideeën de macht te bestormen.’ WIJNAND DUYVENDAK was onder meer directeur van Milieudefensie en van 2002 tot 2008 lid van de Tweede Kamer voor GroenLinks. Sindsdien is hij publicist en initiatiefnemer van diverse klimaatcampagnes. Bureau de Helliπ∆ Wijnand Duyvendak WETENSCHAPPELIJK BUREAU GROENLINKS Wie we zijn en wat we willen Een politieke plaatsbepaling voor GroenLinks Wijnand Duyvendak Inhoudsopgave Inleiding 5 1. Klein is het nieuwe groot 7 2. Oude tijden komen niet meer terug 11 3. Groen en links: een maatschappij heeft een economie maar is geen economie 13 4. Een unieke positie 33 5. De attitude van GroenLinks 41 Tot slot: op naar een evenwichtige samenleving 45 Colofon Tekst: Wijnand Duyvendak Website: www.wijnandduyvendak.nl en www.tripleturnaround.nl Redactionele adviezen: Gerrit Pas Boekverzorging: Daniel Hentschel Uitgave van Bureau de Helling – Wetenschappelijk Bureau GroenLinks Oudegracht 312, Postbus 8008, 3503 RA Utrecht Telefoon: 030 23 999 00 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://bureaudehelling.nl ISBN/EAN 978-90-72288-53-0 NUR 754 Inleiding ‘Alles moet onderwerp van discussie kunnen zijn. -

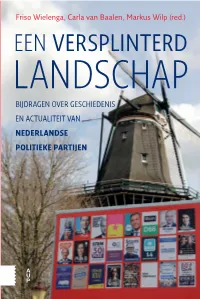

Een Versplinterd Landschap Belicht Deze Historische Lijn Voor Alle Politieke NEDERLANDSE Partijen Die in 2017 in De Tweede Kamer Zijn Gekozen

Markus Wilp (red.) Wilp Markus Wielenga, CarlaFriso vanBaalen, Friso Wielenga, Carla van Baalen, Markus Wilp (red.) Het Nederlandse politieke landschap werd van oudsher gedomineerd door drie stromingen: christendemocraten, liberalen en sociaaldemocraten. Lange tijd toonden verkiezingsuitslagen een hoge mate van continuïteit. Daar kwam aan het eind van de jaren zestig van de 20e eeuw verandering in. Vanaf 1994 zette deze ontwikkeling door en sindsdien laten verkiezingen EEN VERSPLINTERD steeds grote verschuivingen zien. Met de opkomst van populistische stromingen, vanaf 2002, is bovendien het politieke landschap ingrijpend veranderd. De snelle veranderingen in het partijenspectrum zorgen voor een over belichting van de verschillen tussen ‘toen’ en ‘nu’. Bij oppervlakkige beschouwing staat de instabiliteit van vandaag tegenover de gestolde LANDSCHAP onbeweeglijkheid van het verleden. Een dergelijk beeld is echter een ver simpeling, want ook in vroeger jaren konden de politieke spanningen BIJDRAGEN OVER GESCHIEDENIS hoog oplopen en kwamen kabinetten regelmatig voortijdig ten val. Er is EEN niet alleen sprake van discontinuïteit, maar ook wel degelijk van een doorgaande lijn. EN ACTUALITEIT VAN VERSPLINTERD VERSPLINTERD Een versplinterd landschap belicht deze historische lijn voor alle politieke NEDERLANDSE partijen die in 2017 in de Tweede Kamer zijn gekozen. De oudste daarvan bestaat al bijna honderd jaar (SGP), de jongste partijen (DENK en FvD) zijn POLITIEKE PARTIJEN nagelnieuw. Vrijwel alle bijdragen zijn geschreven door vertegenwoordigers van de wetenschappelijke bureaus van de partijen, waardoor een unieke invalshoek is ontstaan: wetenschappelijke distantie gecombineerd met een beschouwing van ‘binnenuit’. Prof. dr. Friso Wielenga is hoogleraardirecteur van het Zentrum für NiederlandeStudien aan de Westfälische Wilhelms Universität in Münster. LANDSCHAP Prof. -

Tilburg University Public Credibility Wisse, E.P

Tilburg University Public credibility Wisse, E.P. Publication date: 2014 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Wisse, E. P. (2014). Public credibility: A study of the preferred personal qualities of cabinet ministers in the Netherlands. Eburon Academic Publishers. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. okt. 2021 Public Credibility A Study of the Preferred Personal Qualities of Cabinet Ministers in the Netherlands Eva Wisse Eburon Delft 2014 ISBN: 978-90-5972-830-1 (paperback) ISBN: 978-90-5972-847-9 (ebook) Eburon Academic Publishers, P.O. Box 2867, 2601 CW Delft, The Netherlands Cover design: Esther Ris, e-riswerk.nl © 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing from the proprietor. -

Geurtz Immune 15-10-2012

Tilburg University Immune to reform? Understanding democratic reform in three consensus democracies Geurtz, J.C.H.C. Publication date: 2012 Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Geurtz, J. C. H. C. (2012). Immune to reform? Understanding democratic reform in three consensus democracies: the Netherlands compared with Germany, and Austria. Optima Grafische Communicatie. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. sep. 2021 Immune to reform? Casper Geurtz ISBN: 978-94-6169-300-6 © Casper Geurtz, 2012 No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, without permission from the author, or, when appropriate, from the publishers of the publications. Layout and printing: Optima Grafische Communicatie, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Immune to reform? Understanding democratic reform in three consensus democracies: the Netherlands compared with Germany, and Austria Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.