3D Multirater RCNN for Multimodal Multiclass Detection and Characterisation of Extremely Small Objects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9634 Extensions of Remarks Hon. Carroll D. Kearns

9634 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD -HOUSE June 2 By Mr. YOUNGER (by request) : notice of a bill introduced in Congress by ~RIVATE BILLS AND RESOLUTIONS H.J. Res. 409. Joint resolution designating the Honorable HALE BOGGS, of Louisiana, to the Luther Burbank Shasta daisy as the encourage investments abroad by· American · Under clause 1 of .rule XXII, private national flower of the United States; to the industry through the establishment of rea bills and resolutions were introduced and Committee on House Administration. sonable taxes on foreign earnings; and of severally referred as follows: By Mr. DORN of New York: ficially commending Congressman BoGGS on By Mr. ANFUSO: H. Con. Res. 191. Concurrent resolution his efforts with respect to this legislation"; H .R. 7513. A bill for the relief of Moses expressing the sense of the Congress with to the Committee on Ways and Means. Licht; to the Committee on the Judiciary. respect to the expulsion of the Republic of By Mr. SCHENCK: Memorial of the Gen H.R. 7514. A bill for the relief of Rocco China from the International Olympic Com eral Assembly of the State of Ohio, memorial Boscattini; to the Committee on the Judi mittee, and with respect to the participation izing the Congress of the United States to C?iary. in the Olympic games of representatives of preserve Ellis Island as a national shrine; to By Mr. DADDARIO: the Republic of China; to the Committee on the Committee on Government Operations. · H .R. 7515. A bill for the relief of Mrs. Foreign Atiairs. By Mr. THORNBERRY: Memorial of the Luigia Lenardon DeCarli; to the Committee By Mr. -

Past Investigations January 2016

Past Investigations January 2016 1/11/2016 - Report #607 12/22/2015 - Report #606 Alton Police Department Ferguson Police Department Commander: Major Jeff Connor Commander: Captain Dan DeCarli Report Writer: Unknown Report Writer: Unknown Homicide Homicide Victim: Romell L. Jones Victim: Tyler Mozee Suspect: Ta'Mon Ford Suspect: Unknown 12/9/2015 - Report #605 11/29/2015 - Report #604 Collinsville Police Department Ferguson Police Department Commander: Maj. Richard Wittenauer Commander: Captain Dan DeCarli Report Writer: Lt. Carole Presson Report Writer: Unknown Homicide Homicide, Robbery, ACA Victim: Daniel Taylor Victim: Sharae Bradford Suspects: Jessie James Werley, Eva Deann Heisch Suspect: Stassie Greer 11/20/2015 - Report #603 11/14/2015 - Report #602 Hazelwood Police Department Hazelwood Police Department Commander: Lt. Mike Brady Commander: Captain Dan DeCarli Report Writer: Unknown Report Writer: Unknown Homicide Homicide Victim: Paul Suntar Victim: Calvin Sharp Suspect: Suspect: 11/9/2015 - Report #601 10/20/2015 - Report #596 Cahokia Police Dept Caseyville PD Commander: Det. Sgt. Jason Donjon Commander: Lt Matt Eiskant Report Writer: S/A Jeri Hochmuth, Sgt Jesse Phillips Report Writer: Lt Dave Vuchich, Det Brian Homicide Riggar Victim: Jermion D. Conley Armed Home Invasion, Murder 1st Suspect: Victim: Nicholas Hood Suspects: Terrion Stevenson, Orlando Adkins Past Investigations January 2016 10/3/2015 - Report #595 9/29/2015 - Report #594 North County Police Cooperative North County Police Cooperative Commander: Unknown Commander: Unknown Report Writer: Unknown Report Writer: Unknown Murder 2nd, ACA Homicide Victim: Melvin Pogue Victim: Jimmy Smith Suspect: Jermaine McDaniels Suspect: 9/9/2015 - Report #593 9/5/2015 - Report #592 Madison City PD Sauget Police Dept Commander: Capt. -

1998-99 Pitt Wrestling Individual Records

1998-99 Pitt Wrestling Individual Records Name Overall Dual Tourney MD F TF Shawn Amistade 22-8 13-1 9-7 6 1 0 Patrick Bainbridge 2-2 0-0 2-2 0 1 0 Kevin Bednarski 1-2 0-0 1-2 0 1 0 Aaron Bibro 0-3 0-0 0-3 0 0 0 Rob Black 1-6 0-0 1-6 0 1 0 Sam Davis 1-3 0-1 1-2 0 1 0 Greg DeBolt 5-6 2-2 3-4 0 3 0 Chris DiGuiseppe 10-10 3-6 7-4 2 1 0 Mike Dixon 9-5 0-0 9-5 0 0 0 Carl Fronhofer 18-4 0-0 18-4 3 0 0 Bobby Fulton 0-2 0-0 0-2 0 0 0 Mike Germano 17-12 4-2 13-10 4 2 1 Chad Jesko 30-10 12-2 18-8 8 2 2 Kevin Johnson 15-10 5-3 10-7 2 0 2 Matt Kaus 1-4 0-0 1-4 1 0 0 Brian Legarth 10-5 1-0 9-5 0 0 1 Rob Loper 17-2 0-0 17-2 4 1 3 Josh McCullough 2-3 0-0 2-3 0 0 0 Nick Mengerink 26-10 13-3 13-7 0 1 4 Mark Mosley 2-1 0-0 2-1 0 0 0 Blaise Mucci 5-3 0-0 5-3 0 1 0 Matt Mueller 26-17 11-5 15-12 2 6 0 Jake Nelson 2-12 0-5 2-7 0 0 0 Kris Neu 1-5 0-1 1-4 0 0 0 Brendan O’Connell 2-3 0-0 2-3 0 0 0 Brian Pardini 15-14 6-3 9-11 2 0 1 Fabian Sciullo 1-5 0-0 1-5 0 0 0 Dan Stine 35-13 13-3 22-10 8 2 0 James Thornton 11-19 4-10 7-9 3 3 0 Andy Villecco 11-13 0-4 11-9 1 0 0 Brad Wood 13-14 1-5 12-9 1 0 0 Mike Ziska 27-13 12-4 15-9 2 0 1 TOTALS 338-239 100-60 238-179 49 27 15 MD – Major Decision; F – Fall; TF – Technical Fall 1998-99 Pitt Wrestling Results Amistade, Shawn WT. -

Validity of Self-Reported Stroke in Elderly African Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Whites

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Validity of Self-reported Stroke in Elderly African Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Whites Christiane Reitz, MD, PhD; Nicole Schupf, PhD; Jose´ A. Luchsinger, MD, MPH; Adam M. Brickman, PhD; Jennifer J. Manly, PhD; Howard Andrews, PhD; Ming X. Tang, PhD; Charles DeCarli, PhD; Truman R. Brown, PhD; Richard Mayeux, MD, MSc Background: The validity of a self-reported stroke re- Results: In analyses of the whole sample, sensitivity of mains inconclusive. stroke self-report for a diagnosis of stroke on MRI was 32.4%, and specificity was 78.9%. In analyses stratified Objective: To validate the diagnosis of self-reported by median age (80.1 years), the validity between re- stroke using stroke identified by magnetic resonance ported stroke and detection of stroke on MRI was sig- imaging (MRI) as the standard. nificantly better in the younger than the older age group (for all vascular territories: sensitivity and specificity, Design, Setting, and Participants: Community- 36.7% and 81.3% vs 27.6% and 26.2%; P=.02). Im- based cohort study of nondemented, ethnically diverse paired memory, cognitive skills, or language ability and elderly persons in northern Manhattan. the presence of hypertension or myocardial infarction were associated with higher rates of false-negative results. Methods: High-resolution quantitative MRIs were ac- quired for 717 participants without dementia. Sensitiv- Conclusions: Using brain MRI as the standard, speci- ity and specificity of stroke by self-report were exam- ficity and sensitivity of stroke self-report are low. Accu- ined using cross-sectional analyses and the 2 test. Putative relationships between factors potentially influencing the racy of self-report is influenced by age, presence of vas- reporting of stroke, including memory performance, cog- cular disease, and cognitive function. -

STATE of CONNECTICUT OFFICE of the SECRETARY of the STATE List of Nominees

STATE OF CONNECTICUT OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF THE STATE List of Nominees Election : 11/05/2019 - November 2019 Municipal Election Town : Ansonia Candidate Name Party Address Mayor--Vote for One 12/01/2019--11/30/2021 Philip Tripp Democratic Party 57 Eagle St., Ansonia, CT David S. Cassetti Republican Party 3 High Acres Rd., Ansonia, CT Aldermen 1st Ward--Vote for Any Two 12/01/2019--11/30/2021 Nina Phipps Democratic Party 60 Rockwood Ave., Ansonia, CT Gary Farrar Jr. Democratic Party 14 Kathy Ln., Ansonia, CT Charles Stowe Republican Party 23 Granite Terr., Ansonia, CT Daniel King Republican Party 70 Woodlawn Ave., Ansonia, CT Aldermen 2nd Ward--Vote for Any Two 12/01/2019--11/30/2021 Tarek Raslan Democratic Party 76 Garden St., Ansonia, CT William Phipps Democratic Party 27 Johnson St., Ansonia, CT Bobbi Tar Republican Party 30 Larovera Terr,, Ansonia, CT Robert Sobolisky Republican Party 26 No. Prospect St., Ansonia, CT Aldermen 3rd Ward--Vote for Any Two 12/01/2019--11/30/2021 Leslie Navarrete Democratic Party 98 Beaver St., Ansonia, CT Joseph Jeanette Jr. Democratic Party 2 Gracie Ln., Ansonia, CT Joseph Cassetti Republican Party 72 Root Ave., Ansonia, CT Domenico Filippone Republican Party 56 Mott St., Ansonia, CT Aldermen 4th Ward--Vote for Any Two 12/01/2019--11/30/2021 Diane Stroman Democratic Party 66 High St., Ansonia, CT Rohan Brown Democratic Party 72 Howard Ave., Ansonia, CT Anthony Spigarolo Republican Party 10 Murray St., Ansonia, CT Aldermen 5th Ward--Vote for Any Two 12/01/2019--11/30/2021 Millie Rios Democratic Party 121 Great Hill Rd., Ansonia, CT Sennea Raslan Democratic Party 217 Wakelee Ave., Ansonia, CT Chicago Rivers Republican Party 19 Tomlinson St., Ansonia, CT Joseph Jaumann Republican Party 183 Wakelee Ave,, Ansonia, CT Aldermen 6th Ward--Vote for Any Two 12/01/2019--11/30/2021 Thomas J. -

Oss Personnel Files - Rg 226 Entry 224 12/23/2010

OSS PERSONNEL FILES - RG 226 ENTRY 224 12/23/2010 LAST NAME FIRST NAME M I RANK or SERIAL BOX NOTES LOCATION Aaberg Caf-3 E T-5 37541999 1 230/86/26/03 Aalbu Sigurd J S/Sgt 37091702 1 230/86/26/03 Aanonsen Olaf H Cpl 32440677 1 230/86/26/03 Abbenante Helen G Cpl A125357 1 230/86/26/03 Abbote Frank Pfc 32985690 1 230/86/26/03 Abbote John A T-3 42048684 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott Delbert H Pvt 35314960 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott Floyd H Pfc 39535381 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott Frederick K Caf-11 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott James E S/Sgt 12063651 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott James F T-5 11102233 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott Norman SP 2/c 5634486 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott Robert J Sgt 12140436 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott Victor J M/Sgt 32455694 1 230/86/26/03 Abee Robert V T-4 34437404 1 230/86/26/03 Abel Arthur A 1st Lt 1181596 1 230/86/26/03 Abel Calvin J T-5 16117938 1 230/86/26/03 Abel John C 1 230/86/26/03 Abele Charles R 1st Lt 462544 1 230/86/26/03 Abele Herbert, Jr. A 2nd Lt 1329784 1 230/86/26/03 Abendschein Norman W Sgt 33191772 1 230/86/26/03 Abernathy James D 1st Lt 343733 1 230/86/26/03 Abney James K 1 230/86/26/03 Abraham Michael K Capt 1010362 1 230/86/26/03 Abrahamovitz Moses T/Sgt 33751543 2 230/86/26/03 Abrahams Isaace L 39090318 1 230/86/26/03 Abrahamson Albert Pvt 32966288 1 230/86/26/03 Abrahamson John D P-4 1 230/86/26/03 Abrams Allen P-7 2 230/86/26/03 Abrams Leonard 2 230/86/26/03 Abrams Melville F T-4 32978088 2 230/86/26/03 Abrams Ruth B Caf-7 2 230/86/26/03 Abrignani Vincent A Maj 1297132 2 230/86/26/03 Abrogast Hazel E Caf-4 2 230/86/26/03 Abromaitis Alexander -

I 10S JAN 1% FPSC-REGORDS/REPORTING 2

1 1 BEFORE THE FLORIDA PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION 2 3 .................................. 4 In the Matter of : DOCKET NO. 950195-WS 5 Application for a rate increase : and increase in service 6 availability charges by SOUTHERN : STATES UTILITIES, INC. for 7 Orange-Osceola Utilities, Inc. in Osceola County, and in 8 Bradford, Brevard, Charlotte, Citrus, Clay, Collier, Duval, 9 Hernando, Highlands, Hillsborough, Lake, Lee, Marion, : 10 Martin, Nassau, Orange, Osceola, : Pasco, Polk, Putnam, Seminole, 11 St. Johns, St. Lucie, Volusia and: Washington Counties. 12 __-_______________________________ 13 14 PROCEEDINGS: OCA= SERVICE HEARING 15 BEFORE : COMMISSIONER J. TERRY DEASON 16 COMMISSIONER JULIA L. JOHNSON COMMISSIONER DIANE K. KIESLING 17 COMMISSIONER JOE GARCIA 18 DATE : Thursday, January 25, 1996 19 TIME: Commenced at 1O:OO a.m. 20 Concluded at 1:00 p.m. 21 PLACE : Ocala Hilton Ballroom 3600 S. W. 36th Avenue 22 Ocala, Florida 23 REPORTED BY: SYDNEY C. SILVA, CSR, RPR 24 Official Commission Reporter 590 25 DOCUMENT NUMREF ATE FLORIDA PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION i 10s JAN 1% FPSC-REGORDS/REPORTING 2 1 APPEARANCES: 2 MATTHEW FEIL, 1000 Color Place, Apopka, 3 Florida, 32703, Telephone No. (407) 880-0058, 4 appearing on behalf of Southern States Utilities, Inc. 5 RALPH JAEGER, Florida Public Service 6 Commission, Division of Legal Services, 2540 Shumard 7 Oak Boulevard, Tallahassee, Florida, 32399-0870, 8 Telephone No. (904) 413-6199, appearing on behalf of 9 the Commission Staff. 10 JACK SHREVE, Public Counsel, and CHARLES J. 11 BECK, Associate Public Counsel, Office of Public 12 Counsel, 111 West Madison Street, Room 812, 13 Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1400, Telephone No. -

Early Stroke Induces Long-Term Impairment of Adult Neurogenesis Accompanied by Hippocampal-Mediated Cognitive Decline

cells Article Early Stroke Induces Long-Term Impairment of Adult Neurogenesis Accompanied by Hippocampal-Mediated Cognitive Decline Carolin Kathner-Schaffert 1, Lina Karapetow 1, Madlen Günther 1, Max Rudolph 1, Mahmoud Dahab 1, Eileen Baum 1, Thomas Lehmann 2, Otto W. Witte 1, Christoph Redecker 1, Christian W. Schmeer 1 and Silke Keiner 1,* 1 Hans-Berger Department of Neurology, Jena University Hospital, Am Klinikum 1, 07747 Jena, Germany; Carolin.Kathner-Schaff[email protected] (C.K.-S.); [email protected] (L.K.); [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (M.R.); [email protected] (M.D.); [email protected] (E.B.); [email protected] (O.W.W.); [email protected] (C.R.); [email protected] (C.W.S.) 2 Institute of Medical Statistics and Computer Science, University Hospital Jena, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, 07743 Jena, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-364-1932-5914 Received: 14 October 2019; Accepted: 12 December 2019; Published: 17 December 2019 Abstract: Stroke increases neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus in the short term, however, long-term effects at the cellular and functional level are poorly understood. Here we evaluated the impact of an early stroke lesion on neurogenesis and cognitive function of the aging brain. We hypothesized that a stroke disturbs dentate neurogenesis during aging correlate with impaired flexible learning. To address this issue a stroke was induced in 3-month-old C57Bl/6 mice by a middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). -

Directory of Federal Financial Managers

I I ne of the objectives of the Joint Financial Management Im rovement Program (JFMIP) is to encourage and *“I’ promote the sharing and exchan e, throughout the federa Pgovernment, of information concernin good financial -0 techniques and practices. Actor B ingly, the JFMIP annually issues the Directory of Federal Financia f Managers to improve communications among federal financial managers, promote an improved climate for financial management, and facilitate sharing of experience and knowledge among financial managers. In order to provide timely and responsive service to the financial management community, the JFMIP asks to be informed of any changes of content. Please contact the JFMIP in writing at the address below: Joint Financial Management Improvement Program Room 3111 441 C Street NW Washington, DC 20548-0001 Any comments, su estions or questions concerning the Directory or any other JFMIP publications should be sent to the above address or faxe 7 to JFMIP ,fax (202) 512-9593. ,, .’ _’ ,I” ., ‘, ,,. “’ ; 9’ :, ! Table of Contents .. : : ’ i s ',,,; ,;,;,1 'i ,’ ,. ,, :. >./ ..I ; ', ,a 1': i Organizational Listing:, Administrative Dffice of the U.S. Courts - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 Labor, Department of, : -----------------,r,---,37 African Development’Foundation - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 LegalServices Corporation ------------------3g Agency for International Development- - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 Library of Congress_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ ‘$9 Agriculture; Depafimentof- L _ I’- _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ -

Gene Expression of Quaking in Sporadic Alzheimer's Disease Patients Is Both Upregulated and Related to Expression Levels of Ge

Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 53 (2016) 209–219 209 DOI 10.3233/JAD-160160 IOS Press Gene Expression of Quaking in Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease Patients is Both Upregulated and Related to Expression Levels of Genes Involved in Amyloid Plaque and Neurofibrillary Tangle Formation Bryn Farnswortha, Christiane Peuckertb, Bettina Zimmermanna, Elena Jazina, Petronella Kettunenc,d and Lina Sors Emilssona,∗ aDepartment of Evolution and Development, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden bDepartment of Neuroscience, Uppsala Biomedical Centre, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden cInstitute of Neuroscience and Physiology, Department of Psychiatry and Neurochemistry, The Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden dDepartment of Neuropathology, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK Handling Associate Editor: Daniela Galimberti Accepted 23 March 2016 Abstract. Quaking (QKI) is a gene exclusively expressed within glial cells. QKI has previously been implicated in various neurological disorders and diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a condition for which increasing evidence suggests a central role of glia cells. The objective of the present study was to investigate the expression levels of QKI and three QKI isoforms (QKI5, QKI6, and QKI7) in AD. Genes that have previously been related to the ontogeny and progression of AD, specifically APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, and MAPT, were also investigated. A real-time PCR assay of 123 samples from human postmortem sporadic AD patients and control brains was performed. The expression values were analyzed with an analysis of covariance model and subsequent multiple regressions to explore the possibility of related expression values between QKI, QKI isoforms, and AD-related genes. -

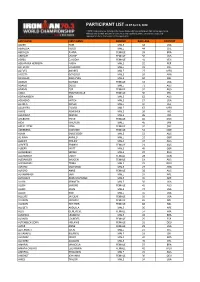

Last Name First Name Gender Race Age Country Aaker

PARTICIPANT LIST AS OF April 6, 2020 * NOTE: Participants List includes only those athletes who have completed their online registration. Although you claimed and paid for your slot at your qualifying event, you are not successfully registered until you finalize your online registration. LAST NAME FIRST NAME GENDER RACE AGE COUNTRY AAKER TOM MALE 58 USA ABARZUA HUGO MALE 44 CHL ABDALLA JUANA FEMALE 39 BRA ABRAMS LAURIE FEMALE 56 USA ABREU CLAUDIA FEMALE 41 VEN ABUAPARA HERRERA NABIH MALE 32 PER ACEVEDO EDUARDO MALE 33 COL ACEVES ANDRES MALE 27 MEX ACOSTA GONZALO MALE 26 ARG ACUSILAS JEAN-YVES MALE 50 BEL ADAMS GLENDA FEMALE 53 USA ADAMS DOUG MALE 71 AUS ADAMS ZOE FEMALE 32 AUS ADDA EMMANUELLE FEMALE 30 PHL ADRIAANSEN KEN MALE 62 AUS ADSHEAD MITCH MALE 27 USA AERDEN DANEK MALE 47 BEL AGUILERA FLAVIO MALE 67 MEX AHIRE ABHISHEK MALE 26 IND AHLAWAT DEEPAK MALE 35 IND AHLBURG TRINE FEMALE 60 DNK AIDA HIROYUKI MALE 45 JPN AIN EL FITRE NINA FEMALE 32 CHE ÅKERBERG SUSANNE FEMALE 52 SWE ALAM EMILE BOEY MALE 53 AUS AL-AWA AHMED MALE 52 GBR ALBERT PHILIPP MALE 37 AUS ALBERTS BRANDI FEMALE 23 AUS ALBERY MATT MALE 45 GBR ALCHEBAEV SERGEI MALE 37 RUS ALEXANDER EMILY FEMALE 28 CAN ALEXANDER IMOGEN FEMALE 19 AUS ALEXANDRU TOMA MALE 29 ROU ALFARO SANTIAGO MALE 27 ARG ALFORD ANNE FEMALE 38 AUS ALHAMMADI SARI MALE 37 ARE ALHOSANI ABDULRAHMAN MALE 36 ARE ALLEN KENNETH MALE 50 USA ALLEN SIMONE FEMALE 41 AUS ALLEN JOHN MALE 72 USA ALLEN ROB MALE 55 USA ALLGIRE JACQUIE FEMALE 56 USA ALLISON MICHELE FEMALE 65 NZL ALLISON HEATHER FEMALE 68 NZL ALLQETI ABDULLA -

Salk Bulletin, April 30, 2018 - May 7, 2018 Date: Friday, April 27, 2018 8:51:00 AM

From: Bulletin To: "[email protected]" Subject: Salk Bulletin, April 30, 2018 - May 7, 2018 Date: Friday, April 27, 2018 8:51:00 AM Salk Bulletin Monday, April 30, 2018 Monday, April 30, 2018 9:30 am “Molecular Control of T Cell Fate in Inflammation and Cancer” Chen Dong, Ph.D., Dean, School of Medicine; Director, Beijing Key Lab on Immunological Studies on Chronic Diseases, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China Immunobiology Seminar Series UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO 1205 Natural Sciences Building Host: Nissi Varki Contact: Andrea Bribiesca, [email protected] Monday, April 30, 2018 3:00 pm – 4:00 pm “Mechanical Motifs in Morphogenesis” L. Mahadevan, Ph.D., Professor, Department of Physics, Applied Mathematics, and Organismic and Evolutionary Biology qBio Seminar Speaker Series UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Natural Sciences Building 1205 Host: Kim Cooper, [email protected] Monday, April 30, 2018 4:00 pm – 5:00 pm “Of Mice And Wo(Men) and Mushrooms that Glow in the Dark: Developing a Novel Drug for Prostate and Ovarian Cancer” Michael J. Kelner, M.D., M.S., Professor of Pathology, University of California, San Diego UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Leichtag Room 107 (Lecture Room) Host: Nissi Varki Contact: Andrea Bribiesca, [email protected] Tuesday, May 1, 2018 Tuesday, May 1, 2018 9:00 am - 10:00 am “Novel Biomarkers of Vascular Brain Injury” UCSD Shiley-Marcos ADRC Neurodegeneration Seminar Charles DeCarli, M.D., Director, Alzheimer’S Disease Center, University of California, Davis UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Leichtag Building, Room 107 Tuesday, May 1, 2018 12:00 pm “Hippo Signaling in Growth Control and Beyond” Duojia Pan, Ph.D.